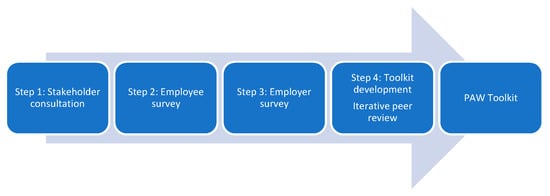

Self-management tools for people with chronic or persistent pain tend to focus on symptom reporting, treatment programmes or exercise and do not address barriers to work, facilitators of work ability, or workplace pain self-management strategies. Researchers developed the Pain at Work (PAW) toolkit, an evidence-based digital toolkit to provide advice on how employees can self-manage their pain at work. In a collaborative-participatory design, 4-step Agile methodology (N = 452) was used to co-create the toolkit with healthcare professionals, employers and people with chronic or persistent pain. Step 1: stakeholder consultation event (n = 27) established content and format; Step 2: online survey with employees who have persistent pain (n = 274) showed employees fear disclosing their condition, and commonly report discrimination and lack of line manager support. Step 3: online employer survey (n = 107) showed employers rarely provide self-management materials or education around managing pain at work, occupational health recommendations for reasonable adjustments are not always actioned, and pain-related stigma is common. Step 4: Toolkit development integrated findings and recommendations from Steps 1–3, and iterative expert peer review was conducted (n = 40). The PAW toolkit provides (a) evidence-based guidelines and signposting around work-capacity advice and support; (b) self-management strategies around working with chronic or persistent pain, (c) promotion of healthy lifestyles, and quality of life at work; (d) advice on adjustments to working environments and workplace solutions to facilitate work participation.

- chronic pain

- self-management

- toolkit

- participatory design

- inclusion

- workforce

- workplace

- occupational health

- digital

- technology

1. Back

1. Introduction

2. Research

Chronic or persistent pain affects between one-third and one-half of the population of the United Kingdom (UK), corresponding to just under 28 million adults. The aim of the study was to develop an evidence-based online toolkit to provide advice on how employees with any chronic or persistent pain condition can self-manage their condition at work. Toolkit development involved co-creation activities together with an interdisciplinary stakeholder group and expert review panel with members from the public, private and third sector. Researchers were to (i) consult with a wider range of stakeholders to establish content and format of the toolkit; (ii) identify employer provisions and challenges relating to supporting employees with chronic or persistent pain; (iii) identify key challenges and support needs of employees with chronic or persistent pain; (iv) conduct iterative expert peer review to complete co-creation of a final toolkit which would be appropriate for use by any employee across all organisation types and size.

2. Research Methods

Rigorous development processes and engagement of stakeholders is essential for development of a high-quality intervention. In a collaborative-participatory design, researchers used an Agile Methodology approach as used in other published evaluations of workplace digital interventions, to develop a digital intervention to support people at work with chronic or persistent pain. The study took place at a higher education institution in England. Development followed a 4-step process (N = 450): (Step 1) a stakeholder consultation event (

n

n

n

n = 40, 13M; 27F). The 4 steps involved stakeholders from academia, healthcare and industry, as well as people with lived experience of chronic or persistent pain. Consultation activities and online survey questions were developed by the research team and were intended to inform toolkit development. Current Agile approach utilised principles of Kanban methodology in which steps 1–3 produced lists of toolkit and development tasks (allowing us to draw from a backlog) and the product (the Pain at Work (PAW) toolkit) was released to reviewers with each update, enabling iterative review. The description of the toolkit aligns with the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) Checklist). The project team had expertise in participatory approaches for digital intervention development and Agile methodology. The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and was classed as educational development and evaluation by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Nottingham Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences.

3. C

To current knowledge, the PAW toolkit is the first accessible, digital resource to support employees at work who have chronic or persistent pain. It is publicly accessible, free to use and was developed through a rigorous, participatory design process involving surveys, consultations and peer review, engaging employees who live with chronic or persistent pain, employers and stakeholders with expertise in workplace issues and/or the management of pain. The toolkit is perceived to be relevant to employees from any size or type of organisation and addresses a clear need identified through review of evidence, stakeholder consultation and surveys with employees and employers.

4 1. Conclusions

Efforts to support self-management of chronic or persistent pain are increasingly important, particularly due to the global work impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. Employers do not currently routinely provide guidance or support for staff with chronic or persistent pain. The PAW toolkit is a new resource to support employees with managing chronic pain at work, co-created with healthcare professionals, employers, and people with persistent pain. The PAW toolkit can be widely implemented to support employees with chronic or persistent pain in the workplace. Disability policies alongside line manager education and training are recommended to foster a psychological safe work environment, maximise employee support and facilitate appropriate actions. Further research could explore the impact of the PAW toolkit on employee pain, wellbeing and support, and organisational outcomes.

2.1. Step 1: Stakeholder Consultation Event

2.2. Step 2: Employee Survey

2.3. Step 3: Employer Survey

2.4. Step 4: Toolkit Development and Expert Peer Review

3. Discussion

Study Limitations and Future Research

References

- Fayaz, A.; Croft, P.; Langford, R.M.; Donaldson, L.J.; Jones, G.T. Prevalence of chronic pain in the UK: A systematic review and meta-analysis of population studies. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e010364.

- Swedish Council on Health Technology Assessment. Methods of Treating Chronic Pain: A Systematic Review; Swedish Council on Health Technology Assessment (SBU): Stockholm, Sweden, 2006.

- Iglesias-López, E.; García-Isidoro, S.; Castellanos-Sánchez, V.O. COVID-19 pandemic: Pain, quality of life and impact on public health in the confinement in Spain. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2021, 10, 4338–4353.

- Shanthanna, H.; Strand, N.H.; Provenzano, D.A.; Lobo, C.A.; Eldabe, S.; Bhatia, A.; Wegener, J.; Curtis, K.; Cohen, S.P.; Narouze, S. Caring for patients with pain during the COVID-19 pandemic: Consensus recommendations from an international expert panel. Anaesthesia 2020, 75, 935–944.

- Mun, C.J.; Campbell, C.M.; McGill, L.S.; Aaron, R.V. The Early Impact of COVID-19 on Chronic Pain: A Cross-Sectional Investigation of a Large Online Sample of Individuals with Chronic Pain in the United States, April to May, 2020. Pain Med. 2021, 22, 470–480.

- Toye, F.; Seers, K.; Allcock, N.; Briggs, M.; Carr, E.; Barker, K. A synthesis of qualitative research exploring the barriers to staying in work with chronic musculoskeletal pain. Disabil. Rehabil. 2016, 38, 566–572.

- Johannes, C.B.; Le, T.K.; Zhou, X.; Johnston, J.A.; Dworkin, R.H. The Prevalence of Chronic Pain in United States Adults: Results of an Internet-Based Survey. J. Pain 2010, 11, 1230–1239.

- Breivik, H.; Collett, B.; Ventafridda, V.; Cohen, R.; Gallacher, D. Survey of chronic pain in Europe: Prevalence, impact on daily life, and treatment. Eur. J. Pain 2006, 10, 287.

- Karoly, P.; Ruehlman, L.S.; Okun, M.A. Psychosocial and demographic correlates of employment vs disability status in a national community sample of adults with chronic pain: Toward a psychology of pain presenteeism. Pain Med. 2013, 14, 1698–1707.

- Jansson, C.; Mittendorfer-Rutz, E.; Alexanderson, K. Sickness absence because of musculoskeletal diagnoses and risk of all-cause and cause-specific mortality: A nationwide Swedish cohort study. Pain 2012, 153, 998–1005.

- Pizzi, L.T.; Carter, C.T.; Howell, J.B.; Vallow, S.M.; Crawford, A.G.; Frank, E.D. Work Loss, Healthcare Utilization, and Costs among US Employees with Chronic Pain. Dis. Manag. Health Outcomes 2005, 13, 201–208.

- Paul, K.; Moser, K. Unemployment impairs mental health: Meta-analyses. J. Vocat. Behav. 2009, 74, 264–282.

- Wegrzynek, P.; Wainwright, E.; Ravalier, J. Return to work interventions for chronic pain: A systematic review. Occup. Med. 2020, 70, 268–277.

- Grant, M.; O-Beirne-Elliman, J.; Froud, R.; Underwood, M.; Seers, K. The work of return to work. Challenges of returning to work when you have chronic pain: A meta-ethnography. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e025743.

- Fragoso, Z.L.; McGonagle, A.K. Chronic pain in the workplace: A diary study of pain interference at work and worker strain. Stress Health 2018, 34, 416–424.

- Agaliotis, M.; Mackey, M.G.; Jan, S.; Fransen, M. Perceptions of working with chronic knee pain: A qualitative study. Work 2018, 61, 379–390.

- Oakman, J.; Kinsman, N.; Briggs, A.M. Working with Persistent Pain: An Exploration of Strategies Utilised to Stay Productive at Work. J. Occup. Rehabil. 2017, 27, 4–14.

- Buruck, G.; Tomaschek, A.; Wendsche, J.; Ochsmann, E.; Dörfel, D. Psychosocial areas of worklife and chronic low back pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2019, 20, 480.

- Palmer, K.T.; Smedley, J. Work relatedness of chronic neck pain with physical findings—A systematic review. Scand. J. Work. Environ. Health 2007, 33, 165–191.

- Agaliotis, M.; Mackey, M.G.; Jan, S.; Fransen, M. Burden of reduced work productivity among people with chronic knee pain: A systematic review. Occup. Environ. Med. 2014, 71, 651–659.

- Patel, A.S.; Farquharson, R.; Carroll, D.; Moore, A.; Phillips, C.; Taylor, R.S.; Barden, J. The Impact and Burden of Chronic Pain in the Workplace: A Qualitative Systematic Review. Pain Pract. 2012, 12, 578–589.

- Kronborg, C.; Handberg, G.; Axelsen, F. Health care costs, work productivity and activity impairment in non-malignant chronic pain patients. Eur. J. Health Econ. 2009, 10, 5–13.

- Maniadakis, N.; Gray, A. The economic burden of back pain in the UK. Pain 2000, 84, 95–103.

- Odenigbo, C.; Julien, N.; Douma, N.B.; Lacasse, A. The importance of chronic pain education and awareness amongst occupational safety and health professionals. J. Pain Res. 2019, 12, 1385–1392.

- Joypaul, S.; Kelly, F.; McMillan, S.S.; King, M.A. Multi-disciplinary interventions for chronic pain involving education: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0223306.

- Geneen, L.J.; Martin, D.J.; Adams, N.; Clarke, C.; Dunbar, M.; Jones, D.; McNamee, P.; Schofield, P.; Smith, B.H. Effects of education to facilitate knowledge about chronic pain for adults: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, 1–21.

- Tegner, H.; Frederiksen, P.; Esbensen, B.A.; Juhl, C. Neurophysiological Pain Education for Patients with Chronic Low Back Pain: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. J. Pain 2018, 34, 778–786.

- Andersen, L.L.; Persson, R.; Jakobsen, M.D.; Sundstrup, E. Psychosocial effects of workplace physical exercise among workers with chronic pain: Randomized controlled trial. Medicine 2017, 96, e5709.

- Skamagki, G.; King, A.; Duncan, M.; Wåhlin, C. A systematic review on workplace interventions to manage chronic musculoskeletal conditions. Physiother. Res. Int. 2018, 23, e1738.

- Sundstrup, E.; Jakobsen, M.D.; Brandt, M.; Jay, K.; Persson, R.; Aagaard, P.; Andersen, L.L. Workplace strength training prevents deterioration of work ability among workers with chronic pain and work disability: A randomized controlled trial. Scand. J. Work. Environ. Health 2014, 40, 244–251.

- Hilton, L.G.; Marshall, N.J.; Motala, A.; Taylor, S.L.; Miake-Lye, I.M.; Baxi, S.; Shanman, R.M.; Solloway, M.R.; Beroesand, J.M.; Hempel, S. Mindfulness meditation for workplace wellness: An evidence map. Work 2019, 63, 205–218.

- Hilton, L.; Hempel, S.; Ewing, B.A.; Apaydin, E.; Xenakis, L.; Newberry, S.; Colaiaco, B.; Maher, A.R.; Shanman, R.M.; Sorbero, M.E.; et al. Mindfulness Meditation for Chronic Pain: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann. Behav. Med. 2017, 51, 199–213.

- Jay, K.; Brandt, M.; Hansen, K.; Sundstrup, E.; Jakobsen, M.D.; Schraefel, M.C.; Sjogaard, G.; Andersen, L.L. Effect of Individually Tailored Biopsychosocial Workplace Interventions on Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain and Stress Among Laboratory Technicians: Randomized Controlled Trial. Pain Physician 2015, 18, 459–471.

- Caputo, G.M.; Di Bari, M.; Orellana, J.N. Group-based exercise at workplace: Short-term effects of neck and shoulder resistance training in video display unit workers with work-related chronic neck pain—A pilot randomized trial. Clin. Rheumatol. 2017, 36, 2325–2333.

- Aas, R.W.; Tuntland, H.; Holte, K.A.; Røe, C.; Lund, T.; Marklund, S.; Moller, A. Workplace interventions for neck pain in workers. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2011, 4, CD008160.

- Bell, J.-A.; Burnett, A. Exercise for the Primary, Secondary and Tertiary Prevention of Low Back Pain in the Workplace: A Systematic Review. J. Occup. Rehabil. 2009, 19, 8–24.

- Shojaei, S.; Tavafian, S.S.; Jamshidi, A.R.; Wagner, J. A Multidisciplinary Workplace Intervention for Chronic Low Back Pain among Nursing Assistants in Iran. Asian Spine J. 2017, 11, 419–426.

- Slattery, B.W.; Haugh, S.; O’Connor, L.; Francis, K.; Dwyer, C.P.; O’Higgins, S.; Egan, J.; McGuire, B.E. An Evaluation of the Effectiveness of the Modalities Used to Deliver Electronic Health Interventions for Chronic Pain: Systematic Review with Network Meta-Analysis. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e11086.

- Macea, D.D.; Gajos, K.; Calil, Y.; Fregni, F. The efficacy of Web-based cognitive behavioral interventions for chronic pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Pain 2010, 11, 917–929.

- Du, S.; Liu, W.; Cai, S.; Hu, Y.; Dong, J. The efficacy of e-health in the self-management of chronic low back pain: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2020, 106, 103507.

- Garg, S.; Garg, D.; Turin, T.C.; Chowdhury, M.F.U.; Allam, A.; Kuijpers, W.; Riva, S.; Schulz, P. Web-Based Interventions for Chronic Back Pain: A Systematic Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2016, 18, e139.

- Slater, H.; Stinson, J.N.; Jordan, J.E.; Chua, J.; Low, B.; Lalloo, C.; Pham, Q.; A Cafazzo, J.; Briggs, A.M. Evaluation of Digital Technologies Tailored to Support Young People’s Self-Management of Musculoskeletal Pain: Mixed Methods Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e18315.

- Minen, M.T.; Torous, J.; Raynowska, J.; Piazza, A.; Grudzen, C.; Powers, S.; Lipton, R.; Sevick, M.A. Electronic behavioral interventions for headache: A systematic review. J. Headache Pain 2016, 17, 1–20.

- Scariot, C.A.; Heemann, A.; Padovani, S. Understanding the collaborative-participatory design. Work 2012, 41 (Suppl. S1), 2701–2705.

- Blake, H.; Bermingham, F.; Johnson, G.; Tabner, A. Mitigating the Psychological Impact of COVID-19 on Healthcare Workers: A Digital Learning Package. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2997.

- Blake, H.; Somerset, S.; Evans, C. Development and Fidelity Testing of the Digital Toolkit for Employers on Workplace Health Checks and Opt-In HIV Testing. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 379.

- Gartshore, E.; Briggs, L.; Blake, H. Development and evaluation of an educational training package to promote health and wellbeing. Br. J. Nurs. 2017, 21, 1182–1186.

- ATLASSIAN Agile Coach: Kanban. How the Kanban Methodology Applies to Software Development. Available online: https://www.atlassian.com/agile/kanban (accessed on 17 November 2021).

- Hoffmann, T.; Glasziou, P.; Boutron, I.; Milne, R.; Perera, R.; Moher, D.; Altman, D.; Barbour, V.; Macdonald, H.; Johnston, M.; et al. Better reporting of interventions: Template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ 2014, 348, 1687.

- Agile Alliance, Manifesto for Agile Software Development. 2001. Available online: https://www.agilealliance.org/agile101/the-agile-manifesto/ (accessed on 4 November 2021).

- Ruiz, J.G.; Candler, C.; Teasdale, T.A. Peer Reviewing E-Learning: Opportunities, Challenges, and Solutions. Acad. Med. 2007, 82, 503–507.

- The University of Nottingham. The Xerte Project. Available online: https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/xerte/index.aspx (accessed on 17 November 2021).

- Bertin, P.; Fagnani, F.; Duburcq, A.; Woronoff, A.-S.; Chauvin, P.; Cukierman, G.; Tropé-Chirol, S.; Joubert, J.-M.; Kobelt, G. Impact of rheumatoid arthritis on career progression, productivity, and employability: The PRET Study. Jt. Bone Spine 2016, 83, 47–52.

- Shahnasarian, M. Career Rehabilitation: Integration of Vocational Rehabilitation and Career Development in the Twenty-First Century. Career Dev. Q. 2001, 49, 275–283.

- Smith, B.H.; Elliott, A.M.; Chambers, W.A.; Smith, W.C.; Hannaford, P.C.; Penny, K. The impact of chronic pain in the community. Fam. Pract. 2001, 18, 292–299.

- de Vries, H.J.; Reneman, M.F.; Groothoff, J.W.; Geertzen, J.H.B.; Brouwer, S. Factors promoting staying at work in people with chronic nonspecific musculoskeletal pain: A systematic review. Disabil. Rehabil. 2012, 34, 443–458.

- Tick, H.; Nielsen, A.; Pelletier, K.R.; Bonakdar, R.; Simmons, S.; Glick, R.; Ratner, E.; Lemmon, R.L.; Wayne, P.; Zador, V. Pain Task Force of the Academic Consortium for Integrative Medicine and Health. Evidence-Based Nonpharmacologic Strategies for Comprehensive Pain Care: The Consortium Pain Task Force White Paper. Explore 2018, 14, 177–211.

- Geneen, L.J.; Moore, R.A.; Clarke, C.; Martin, D.; Colvin, L.A.; Smith, B.H. Physical activity and exercise for chronic pain in adults: An overview of Cochrane Reviews. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 4, CD011279.

- Searle, A.; Spink, M.; Ho, A.; Chuter, V. Exercise interventions for the treatment of chronic low back pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Clin. Rehabil. 2015, 29, 1155–1167.

- Arimi, S.A.; Bandpei, M.A.M.; Javanshir, K.; Rezasoltani, A.; Biglarian, A. The Effect of Different Exercise Programs on Size and Function of Deep Cervical Flexor Muscles in Patients with Chronic Nonspecific Neck Pain: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2017, 96, 582–588.

- Kong, L.; Lauche, R.; Klose, P.; Bu, J.H.; Yang, X.C.; Guo, C.Q.; Dobos, G.; Cheng, Y.W. Tai Chi for Chronic Pain Conditions: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 25325.

- Cramer, H.; Klose, P.; Brinkhaus, B.; Michalsen, A.; Dobos, G. Effects of yoga on chronic neck pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Rehabil. 2017, 11, 1457–1465.

- Patti, A.; Bianco, A.; Paoli, A.; Messina, G.; Montalto, M.A.; Bellafiore, M.; Battaglia, G.; Iovane, A.; Palma, A. Effects of Pilates exercise programs in people with chronic low back pain: A systematic review. Medicine 2015, 94, e383.

- Wells, C.; Kolt, G.S.; Marshall, P.; Hill, B.; Bialocerkowski, A. The effectiveness of Pilates exercise in people with chronic low back pain: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e100402.

- Brain, K.; Burrows, T.L.; Rollo, M.E.; Chai, L.K.; Clarke, E.D.; Hayes, C.; Hodson, F.J.; Collins, C.E. A systematic review and meta-analysis of nutrition interventions for chronic noncancer pain. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2019, 32, 198–225.

- Ball, E.; Sharizan, E.N.S.M.; Franklin, G.; Rogozinska, E. Does mindfulness meditation improve chronic pain? A systematic review. Curr. Opin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017, 29, 359–366.

- Nelson, N.L.; Churilla, J.R. Massage Therapy for Pain and Function in Patients with Arthritis: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2017, 96, 665–672.

- Vickers, A.J.; Cronin, A.M.; Maschino, A.C.; Lewith, G.; MacPherson, H.; Foster, N.E.; Sherman, K.J.; Witt, C.M.; Linde, K. Acupuncture Trialists’ Collaboration. Acupuncture for chronic pain: Individual patient data meta-analysis. Arch. Intern. Med. 2012, 172, 1444–1453.

- Hughes, L.S.; Clark, J.; Colclough, J.A.; Dale, E.; McMillan, D. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) for Chronic Pain: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses. Clin. J. Pain 2017, 33, 552–568.

- Veehof, M.M.; Trompetter, H.R.; Bohlmeijer, E.T.; Schreurs, K.M.G. Acceptance and mindfulness-based interventions for the treatment of chronic pain: A meta-analytic review. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2016, 45, 5–31.

- Williams, A.C.; Eccleston, C.; Morley, S. Psychological therapies for the management of chronic pain (excluding headache) in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2012, 11, CD007407.

- Thabrew, H.; Stasiak, K.; Hetrick, S.E.; Wong, S.; Huss, J.H.; Merry, S.N. E-Health interventions for anxiety and depression in children and adolescents with long-term physical conditions. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 8, CD012489.

- Sander, L.B.; Paganini, S.; Terhorst, Y.; Schlicker, S.; Lin, J.; Spanhel, K.; Buntrock, C.; Ebert, D.D.; Baumeister, H. Effectiveness of a Guided Web-Based Self-help Intervention to Prevent Depression in Patients with Persistent Back Pain: The PROD-BP Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Psychiatry 2020, 27, e201021.

- Orhan, C.; Van Looveren, E.; Cagnie, B.; Mukhtar, N.B.; Lenoir, D.; Meeus, M. Are Pain Beliefs, Cognitions, and Behaviors Influenced by Race, Ethnicity, and Culture in Patients with Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain: A Systematic Review. Physician 2018, 21, 541–558.

- Federation of Small Businesses (FSB). UK Small Business Statistics. Business Population Estimates for the UK and Regions in 2020. Available online: https://www.fsb.org.uk/uk-small-business-statistics.html (accessed on 21 November 2021).

- Arocena, P.; Núñez, I. An empirical analysis of the effectiveness of occupational health and safety management systems in SMEs. Int. Small Bus. J. 2010, 28, 398–419.

- Clark, T.R. The 4 Stages of Psychological Safety: Defining the Path to Inclusion and Innovation; Berrett-Koehler: Oakland, CA, USA, 2020.

- Grant, M.; Rees, S.; Underwood, M.; Froud, R. Obstacles to returning to work with chronic pain: In-depth interviews with people who are off work due to chronic pain and employers. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2019, 20, 486.

- Mirpuri, S.; Gill, P.; Ocampo, A.; Roberts, N.; Narang, B.; Hwang, S.W.; Gany, F. Discrimination and Health Among Taxi Drivers in New York and Toronto. J. Community Health 2018, 43, 667–672.

- Lee, N.; Sung, H.; Kim, J.-H.; Punnett, L.; Kim, S.-S. Perceived discrimination and low back pain among 28,532 workers in South Korea: Effect modification by labor union status. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 177, 198–204.

- Carney, J. A Step Toward a Cultural Transformation in the Way Pain is Perceived, Judged and Treated. Practical Bioethics: A blog of the Centre for Practical Bioethics. 2015. Available online: http://practicalbioethics.blogspot.com/2015/07/a-step-toward-cultural-transformation.html (accessed on 21 November 2021).

- Nielson, A. Journeys with Chronic Pain: Acquiring Stigma along the Way. In At the Edge of Being: The Aporia of Pain; McKenzie, H., Quintner, J., Bendelow, G., Eds.; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 83–97.

- Clauw, D.J.; Häuser, W.; Cohen, S.P.; Fitzcharlesf, M.A. Considering the potential for an increase in chronic pain after the COVID-19 pandemic. Pain 2020, 161, 1694–1697.

- Puntillo, F.; Giglio, M.; Brienza, N.; Viswanath, O.; Urits, I.; Kaye, A.D.; Pergolizzi, J.; Paladini, A.; Varrassi, G. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on chronic pain management: Looking for the best way to deliver care. Best Pr. Res. Clin. Anaesthesiol. 2020, 34, 529–537.

- Nyblade, L.; Stockton, M.A.; Giger, K.; Bond, V.; Ekstrand, M.L.; Mc Lean, R.; Mitchell, E.M.H.; Nelson, L.R.E.; Sapag, J.C.; Siraprapasiri, T.; et al. Stigma in health facilities: Why it matters and how we can change it. BMC Med. 2019, 17, 25.

- Kirk-Brown, A.; Van Dijk, P. An empowerment model of workplace support following disclosure, for people with MS. Mult. Scler. J. 2014, 20, 1624–1632.