Solid organ transplant (SOT) is an effective therapy for end-stage diseases and organ failures, which is a lifesaving, transformational and restorative procedure for improving the quality and longevity of life. SOT relies on the effective surveillance of graft which includes serial laboratory testing and biopsies. The immune system acts on all foreign particles that enter the body and produces antibodies in response. Similarly, when an organ is transplanted, the immune system recognizes it and acts against it, consequently destroying the perceived foreign cells in the form of the transplanted organ. Due to the huge gap between the need and availability of organs, one cannot risk an organ failure after a transplant, owing merely to the immune response. To overcome this several measures are taken at each step, right from the beginning where the best suitable match for the organ is searched for, succeeded by the advanced medications and immunotherapy given to the recipients in order to suppress the immune response, until the enhanced post-transplant patient care. Post-transplant recipients are kept under surveillance and strict regimes to avoid any complications that may lead to either damage or rejection of the transplanted organ. Around 7% of renal transplants fail after a year, 17% fail after 3 years, and 46% fail after 10 years. Among heart transplants, about 10% of the transplants fail in one year and 30% in 5 years. Similarly, among liver transplant recipients around 20% of failures are reported in 1 year and 30% of failures in 5 years, thereby making graft rejection a pertinent obstacle in transplantation.

Solid organ transplant (SOT) is an effective therapy for end-stage diseases and organ failures, which is a lifesaving, transformational and restorative procedure for improving the quality and longevity of life. SOT relies on the effective surveillance of graft which includes serial laboratory testing and biopsies. The immune system acts on all foreign particles that enter the body and produces antibodies in response. Similarly, when an organ is transplanted, the immune system recognizes it and acts against it, consequently destroying the perceived foreign cells in the form of the transplanted organ [4,5]. Due to the huge gap between the need and availability of organs, one cannot risk an organ failure after a transplant, owing merely to the immune response. To overcome this several measures are taken at each step, right from the beginning where the best suitable match for the organ is searched for, succeeded by the advanced medications and immunotherapy given to the recipients in order to suppress the immune response, until the enhanced post-transplant patient care.

Post-transplant recipients are kept under surveillance and strict regimes to avoid any complications that may lead to either damage or rejection of the transplanted organ [6,7]. Around 7% of renal transplants fail after a year, 17% fail after 3 years, and 46% fail after 10 years [8]. Among heart transplants, about 10% of the transplants fail in one year and 30% in 5 years [9,10,11]. Similarly, among liver transplant recipients around 20% of failures are reported in 1 year and 30% of failures in 5 years [12,13], thereby making graft rejection a pertinent obstacle in transplantation.

1. Background

Large-scale screening processes undertaken in the 2000s in Australia, Norway, and the United States revealed that more than 10% of adults had markers for chronic kidney disease (CKD). The prevalence of CKD is in 9.1% of the global population

[1][14]. More than 500,000 people in the United States live with ESRD

[2][15]. Heart failure is a global health issue, with a prevalence of over 23 million cases worldwide

[3][16]. It is predicted that by the end of 2030; 3 million additional patients will be added to these figures

[4][17]. One out of every nine deaths in America is caused by heart failure

[5][18]. There were 112 million reported cases of prevalent compensated cirrhosis and 10.2 million cases of decompensated cirrhosis worldwide, in 2017

[6][19]. The figures are indicative of the rising cases of organ failures and thereby hint at a scenario of unaffordable graft rejections.

After transplantation patients are required to undergo biopsy in order to diagnose graft dysfunction or rejection. Therefore, there is a pressing need to explore potential biomarkers which could be used as early detection mechanisms for monitoring graft health, graft damage, and rejection. The currently available non-invasive methods to detect damage and rejection are insufficient and donor-derived cell-free DNA (dd-cfDNA) seems to be very promising as a non-invasive biomarker.

2. Evolution of Analytical Approaches and Techniques to Diagnose Graft Rejection Using dd-cfDNA

Thomas Earl Starzl, an American physician who performed the first liver transplant in humans, provided the first ever well-defined evidence for the presence of donor DNA in the bloodstream of a recipient, which was ascertained by karyotyping studies in female recipients of liver transplants who obtained a graft from cadaveric male donors and proved that the organ genome becomes chimera in transplanted patients

[7][20]. ‘Graft chimerism might be a generic feature of all accepted graft’ was theorized after the evidence of chimeras observed in intestine, kidney, lung, heart, and liver transplants

[8][9][10][11][12][21,22,23,24,25].

Evidence of the presence of Y chromosomes in the recipient’s urine and plasma of sex-mismatched donor-recipient pairs revealed that increased level of dd-cfDNA could be an indicator for rejection and acceptance of the graft

[13][14][15][16][17][26,27,28,29,30]. A major drawback of this approach was that it was pertinent only to a female recipient who obtained an organ from a male donor. Therefore, this limited the number of transplant cases and reduced its applicability in a minority of cases. Despite its limitations, it led to the genesis of the idea of microchimerism, which is the presence of small amounts of cells originated from another individual having different genetic information from the host.

This microchimerism directed the researchers and scientists to identify and quantify the donor DNA in the recipient by discovering an assay which could be applicable to all the recipients irrespective of age, sex and the type of organ transplanted. Hence a universal, sex-independent assay was introduced which required the genotyping of both donor and recipient. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP), which are homozygous and can distinguish donor DNA from recipient DNA, were selected for further analysis and quantification. This method relied upon knowledge of donor and recipient genotypes, which required time, a donor sample, and was costly. Shotgun sequencing was not possible in a regular hospital setting because of its high turnaround time and because genotyping both the donor and recipient was time- and effort-constraining.

Thus, the proposed technique takes a leap over the need of genotyping both the donor and recipient as it proposes the uses of the assay of preselected SNPs which are applicable to all donor recipients’ pairs, irrespective of age, sex, ethnicity, and organs. An SNP should be homozygous in both donor and recipient, and should differ between the two. To select such SNPs, we can either genotype both donors and recipients and select the homozygous different SNPs which identify donor DNA and can be further quantified. The other approach is preselecting a panel of informative SNPs from the public genomic databases like HapMap, 1000 Genomes, and Indi Genomes. This informative panel of preselected SNPs contains SNPs with high minor allele frequency (MAF) of 0.4–0.5. The SNPs selected should not be located within or directly adjacent to an annotated repetitive element. Considering the Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium an SNP with an MAF of 0.4–0.5 has a nearly equal distribution of both alleles in a population and an 11.5 to 12.5% chance of containing a homozygous genotype in two individuals: the recipient and the donor. It has approximately a 23–25% chance of being homozygous for each allele in an individual. Hence, an informative panel of a set of 30–35 SNPs is enough to identify 3 SNPs for each donor–recipient pair to assess the damage and rejection in the recipient

[18][31]. However, if SNPs were selected randomly without the required MAF, then approximately 3000 SNPs would be available to test for homozygosity between the donor and the recipient

[19][32].

Presently, there are two simultaneous techniques for using dd-cfDNA; as biomarkers, based on the measurement of the number of donor molecules by next-generation sequencing or the digital PCR method. The next-generation sequencing method uses 266 SNPs panel in comparison to 41 SNPs used by the droplet digital method by Beck et al.

[19][20][32,33]. Both of these methods lead to the same results

[21][34].

An individual genome carries approximately 4–5 million SNPs and there are more than 100 million SNPs across the populations globally. Only 0.1–1% of DNA differ between any two individuals, depending on the degree of relatedness

[22][35]. An SNP may be unique to an individual or a population. In forensic science, SNPs are used to establish identities. Similarly, the SNPs are used in transplantation for identifying different DNA circulating in the plasma of the recipient.

Genomic biomarkers are more complex than standard chemistry diagnostics. Hence, they require advanced methods, workflows, and analytical approaches. The assays detecting dd-cfDNA differ in technology and methods. Therefore, each of the assays requires clinical validation before introducing it in a clinical setting. The chronology of the advancement and use of different methods and techniques for identifying and quantifying the donor-derived cell-free DNA during the last two decades are elucidated in Table 1.

Table 1. A timeline comparison of methods and techniques to assess dd-cfDNA to diagnose rejection.

| Name |

Organ(s) |

Sample Type |

dd-cfDNA Method |

Technique |

Donor Sample Required |

| PPV (%) |

NPV (%) |

|---|

| Zhang 1999 [13] | Zhang 1999 [26] |

Kidney |

Urine |

Sex mismatch (SRY gene) |

Real-time quantitative PCR |

No |

| Moiera 2009 [14] | Moiera 2009 [27] |

Kidney |

Plasma, Urine |

89 |

85 |

53 |

98 |

| Moreira 2009 [14] | Moreira 2009 [27] |

| Sigdel 2013 [ | Kidney |

Plasma, Urine |

Hemoglobin, beta (HBB) gene & TSPY1 gene |

16 | Quantitative PCR |

] | Yes |

| Sigdel 2013 [29] |

Kidney |

Urine |

81 |

75 |

- |

- |

Synder 2011 [17] | Synder 2011 [30] |

Heart |

Plasma |

Sex mismatch (Chr Y) & shotgun sequencing |

| Schutz 2016 | Digital PCR |

[ | Yes |

| 28] | Schutz 2016 [41] |

Liver |

Plasma |

91.2 |

92.5 |

- |

- |

Sigdel 2013 [16] | Sigdel 2013 [29] |

Kidney |

Urine |

Sex mismatch (SRY gene) |

| Schutz 2017 [32] | Schutz 2017 [3 | Digital PCR |

] | No |

| Liver |

Plasma |

90.3 |

92.9 |

- |

- |

Beck 2013 [19] | Beck 2013 [32] |

Heart, Kidney, Liver |

Plasma |

Informative SNP panel |

Droplet digital PCR |

| Bloom 2017 [ | No |

| 33] | Bloom 2017 [45] |

Kidney |

Plasma |

81 |

83 |

44 |

96 |

Vlaminck 2014 [23] | Vlaminck 2014 [36] |

Heart |

Plasma |

Whole-genome arrays |

Quantitative PCR |

Yes |

| Jordan 2018 [35] | Jordan 2018 [47] |

Kidney |

Plasma |

81 |

82 |

81 |

83 |

Macher 2014 [15] | Macher 2014 [28] |

Liver |

| Weir 2018 [21] | Plasma |

Weir 2018 [ | SRY & beta-globin gene |

34] | Real time quantitative PCR |

No |

| Kidney |

Plasma |

69.6 |

84 |

60.9 |

88.6 |

Vlaminck 2015 [24] | Vlaminck 2015 [37] |

Lungs |

Plasma |

| Khush 2019 | Whole-genome arrays |

Quantitative PCR |

Yes |

| [39] | Khush 2019 [50] |

Heart |

Plasma |

80 |

44 |

8.7 |

97.1 |

Beck 2015 [25] | Beck 2015 [38] |

Heart, Kidney |

Plasma |

Informative SNP panel |

| Sigdel 2019 [41 | Droplet digital PCR |

] | No |

| Sigdel 2019 [52] |

Kidney |

Plasma |

88.7 |

72.6 |

52 |

95 |

Burnham 2016 [26] | Burnham 2016 [39] |

Lungs |

Plasma |

SNP sequencing with mitochondrial reference sequences |

| Oellerich 2019 | Quantitative PCR |

[ | Yes |

| 42] | Oellerich 2019 [53] |

Kidney |

Plasma |

73 |

73 |

13 |

98 |

Macher 2016 [27] | Macher 2016 [40] |

Liver |

| Sayah 2020 [43] | Plasma |

RH-negative recipient & RH-positive donor pair |

Real time PCR |

Sayah 2020 [ | Yes |

| 54] |

Lung |

Plasma |

73.1 |

52.9 |

34 |

85.5 |

Grskovic 2016 [20] | Grskovic 2016 [33] |

Heart, Kidney |

Plasma |

Informative SNP panel |

Next-generation sequencing |

| Levine 2020 [ | No |

| 63] | Levine 2020 [73] |

Lung |

Plasma |

81 |

100 |

- |

- |

Schutz 2016 [28] | Schutz 2016 [41] |

Liver |

Plasma |

Informative SNP panel |

Droplet digital PCR |

No |

| Richmond 2020 [64] | Richmond 2020 [74] |

Heart |

Plasma |

75 |

79 |

- |

- |

Zou 2017 [29] | Zou 2017 [42] |

Lung |

Plasma |

HLA specific primers and probes |

| Puliyanda 2020 | Droplet digital PCR |

[47] | Puliyanda 2020 [ | No |

| 58] |

Lung |

Plasma |

86 |

100 |

Bromberg 2017 [30] | Bromberg 2017 [43] |

Kidney |

Plasma |

Informative SNP panel |

Next-generation sequencing |

No |

| - |

- |

| Zhao 2021 [65] | Zhao 2021 [75] |

Liver |

Plasma |

81.8 |

81.9 |

56.2 |

93.9 |

Goh 2017 [31] | Goh 2017 [44] |

Liver |

Plasma |

Deletion/Insertion Polymorphism (DIP) panel |

| Khush 2021 [49] | Droplet digital PCR |

Khush 2021 [ | Yes |

| 60 |

Schutz 2017 [32] | Schutz 2017 [3] |

Liver |

Plasma |

Informative SNP panel |

Droplet digital PCR |

No |

| Bloom 2017 [33] | Bloom 2017 [45] |

Kidney |

Plasma |

Informative SNP panel |

Next-generation sequencing |

No |

| Tanaka 2018 [34] | Tanaka 2018 [46] |

Lung |

Plasma |

SNP genotyping & informative SNP panel |

Droplet digital PCR |

Yes |

| Jordan 2018 [35] | Jordan 2018 [47] |

Kidney |

Plasma |

Informative SNP panel |

Next-generation sequencing |

No |

| Weir 2018 [21] | Weir 2018 [34] |

Kidney |

Plasma |

Informative SNP panel |

Next-generation sequencing |

No |

| Beck 2018 [36] | Beck 2018 [2] |

Heart |

Plasma |

Informative SNP panel |

Droplet digital PCR |

No |

| Gielis 2018 [37] | Gielis 2018 [48] |

Kidney |

Plasma |

Multiplex PCR assay |

Next-generation sequencing |

Yes |

| Goh 2019 [38] | Goh 2019 [49] |

Liver |

Plasma |

Deletion/Insertion Polymorphism (DIP) panel |

Droplet digital PCR |

Yes |

| Khush 2019 [39] | Khush 2019 [50] |

Heart |

Plasma |

Informative SNP panel |

Next-generation sequencing |

No |

| Altug 2019 [40] | Altug 2019 [51] |

Kidney |

Plasma |

Bi-allelic SNP on Chr-2,13,18,21 |

Massively multiplexed PCR |

No |

| Sigdel 2019 [41] | Sigdel 2019 [52] |

Kidney |

Plasma |

SNP-based assay & LabChip NGS 5k |

Massively multiplex PCR-next-generation sequencing |

No |

| Oellerich 2019 [42] | Oellerich 2019 [53] |

Kidney |

Plasma |

Informative SNP panel |

Droplet digital PCR |

No |

| Sayah 2020 [43] | Sayah 2020 [54] |

Lung |

Plasma |

Informative SNP panel |

Next-generation sequencing |

No |

| Potter 2020 [44] | Potter 2020 [55] |

Kidney |

Plasma |

Informative SNP panel |

Next-generation sequencing |

No |

| Schutz 2020 [45] | Schutz 2020 [56] |

Kidney |

Plasma |

Informative SNP panel |

Droplet digital PCR |

No |

| Shen 2020 [46] | Shen 2020 [57] |

Kidney |

Plasma |

Informative SNP panel |

Next-generation sequencing |

No |

| Puliyanda 2020 [47] | Puliyanda 2020 [58] |

Lung |

Plasma |

Informative SNP panel |

Next-generation sequencing |

No |

| Stites 2020 [48] | Stites 2020 [59] |

Kidney |

Plasma |

Informative SNP panel |

Next-generation sequencing |

No |

| Khush 2021 [49] | Khush 2021 [60] |

Lung |

Plasma |

Informative SNP panel |

Next-generation sequencing |

No |

3. The dd-cfDNA as a Potential Biomarker

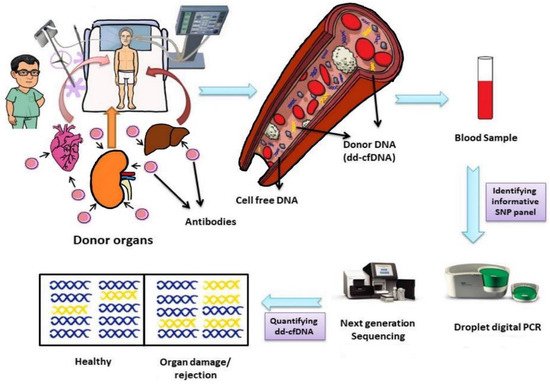

Donor-derived cell-free DNA (dd-cfDNA), also referred to as graft cell-free DNA (GcfDNA) or donor-specific DNA (ds-DNA), is a biomarker which works on the principle/fact that an organ transplant is not just a transplant of an organ but also the transplant of a genome. The biological rationale behind the utility of dd-cfDNA is that the immune system is activated upon recognition of the transplanted organ and produces antibodies in response. The antibodies attack the transplanted organ which leads to apoptosis or cell necrosis. The ruptured or dead cells release their contents into the recipient’s blood plasma and thereafter, the recipient carries the DNA of the donor, which reflects in its name, ‘donor-derived cell-free DNA’. This is cell-free, circulating and donor DNA.

Donor-derived cell-free DNA is found in all recipients irrespective of whether the recipient shows rejection or not, although the number of cells may vary from individual to individual (

Figure 12)

[7][20]. Furthermore, even after using different methods for the identification and quantification of dd-cfDNA, in stable patients similar median values are obtained

[50][61].

Figure 12. Life cycle of donor-derived cell-free DNA, its identification and quantification. Abbreviations: dd-cfDNA, donor-derived cell-free DNA; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism.

Large numbers of donor cells are present in individuals experiencing graft damage and/or rejection due to the breakdown of cells.

The clearance of dd-cfDNA from an individual’s body is similar to that of cell-free DNA, though it is still being studied and requires further research.

The half-life of cell-free DNA in the bloodstream is between 16 min to 2.5 h

[51][52][62,63]. Cell-free DNA can enter the liver or spleen and be degraded by the macrophages that are located inside by the action of the DNase I enzyme

[53][64]. Cell-free DNA can also be excreted through urine.

The pertinent questions that open the purview of the discussion concerning “whether dd-cfDNA is cleared out from the body through urine?” and “Is increased level of dd-cfDNA associated with impaired kidney function rather than actual graft damage?” Some insight can be gained even though it is unknown which mechanism is involved in clearing out the cell-free DNA from the blood plasma of the recipient, but a study on foetal DNA cleared out from maternal blood circulation showed that only 0.2 to 19% of the total foetal DNA is cleared out by the kidney, stating that renal excretion is not a major route when it comes to the clearance of non-host (foetal) DNA

[54][65]. Donor DNA is always present in the plasma of the recipient in varying quantities.

The recipient also carries its own cell-free DNA. So, the quantification of donor DNA will help to monitor the graft health, damage and rejection. For the quantification of dd-cfDNA, SNPs are best-suited as they can differentiate dd-cfDNA from the recipient cf-DNA. The polymorphism between the donor and the recipient must be identified. Therefore, for diagnosing graft damage and rejection, the panel of SNPs used must be able to differentiate between individuals.

Currently used methods for monitoring the organ health and diagnosing the rejection are based on signs and symptoms of patient, biochemistry tests, immunological assays, and biopsies. Serum creatinine (sCr) is increased if there is a significant reduction in the glomerular filtration rate (GFR), and about 50% of the kidney function is lost before a rise in sCr is detected, hence making it a late marker for acute rejection

[55][66].

Biopsy being a ‘gold standard’ for assessing the health and rejection of an organ is an invasive technique and has its own set of limitations, including the turnaround time, expense, inconvenient process, chances of sampling error, inter-observer variability and poor recommendation for serial testing. Biopsies are performed on suspicion of damage or graft rejection and almost 50% or more of the organ is typically injured before it is recommended for biopsy

[55][56][57][66,67,68]. Due to this, asymptomatic graft injuries remain undiagnosed. However, endomyocardial biopsy is also not a true gold standard for diagnosing acute rejection

[39][50].

Approximately 25% of biopsies yield an inadequate specimen and this risk can become larger with a smaller needle size. Because of the modern immunosuppression, many units no longer perform routine biopsies

[58][69]. In a study by Bloom et al. it was found that only 27% of the clinically indicated biopsies in kidney transplant patients revealed active rejection, where the biopsies were performed after observing an elevation in the sCr over baseline

[23][36]. In another study by Yang et al., 43% of the clinically indicated biopsies were found quiescent and 65% of the protocol biopsies were tagged as unnecessary invasive procedures

[59][4].

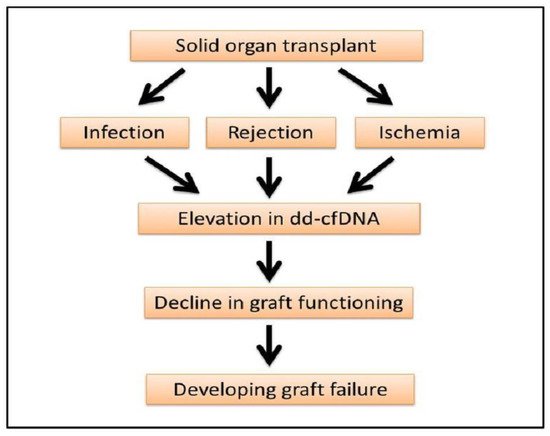

45. Monitoring of Organ Damage and Rejection through dd-cfDNA

The monitoring of dd-cfDNA is based on the number of donor DNA copies circulating in the plasma of recipients. The levels of dd-cfDNA in stable patients are significantly less when compared to rejection cases. High levels of dd-cfDNA are associated with the rejection cases in liver, kidney, heart, lung transplant recipients

[14][15][16][17][19][20][21][23][24][25][26][27][29][30][31][35][37][38][39][41][42][60][61][62][27,28,29,30,32,33,34,36,37,38,39,40,42,43,44,47,48,49,50,52,53,70,71,72]. The dd-cfDNA levels begin to rise from weeks to months before acute rejection is diagnosed by the currently used methods. These increased levels represent early graft damage or injury

[32][17][23][3,30,36]. The dd-cfDNA is highly efficient in detecting injury and rejection caused due to antibody mediated rejection (ABMR). But, when it comes to T-cell mediated rejection (TCMR), some studies have also shown that TCMR is associated with elevation in dd-cfDNA. TCMR type IB, type IIA, type IA and borderline rejection shows a high percentage of dd-cfDNA, but according to a study by Sigdel et al., it is averred that the dd-cfDNA method is unable to detect TCMR

[33][41][42][48][45,52,53,59]. Further studies are needed to assess the role of dd-cfDNA in detecting TCMR rejection.

The elevation of dd-cfDNA is not always linked to rejection but also points out the degree of graft injury and infection. Immediately post-transplant the level of dd-cfDNA is increased but decreases after a couple of days of kidney transplant, liver transplant, lung transplant and heart transplant, which is also reflective of ischemia or reperfusion injuries in the transplanted organs (

Figure 23)

[13][19][26][28][35][37][26,32,39,41,47,48].

Figure 23. Progression of organ transplant to graft failure. Elevation of dd-cfDNA can be an early indicator of graft damage, rejection and failure.

The levels of dd-cfDNA are affected by anti-rejection therapy and are dose-dependent. Levels of dd-cfDNA decrease rapidly after anti-rejection therapy

[46][57]. This paves the way for us to create personalized immunosuppressive drugs to prevent graft damage and rejection. Furthermore, this will also help to minimize the risk of other diseases, caused by the suppressed immune system of the body and high dosage of immunosuppressive medicines.

It is reported through 16 studies upon the utility and effectiveness of dd-cfDNA in detecting rejection among kidney, heart, liver and lung transplants that the mean sensitivities and specificities of dd-cfDNA are 79.83 ± 9.15% and 79.61 ± 14.86%, respectively (see

Table 2). These studies detail the efficiency of dd-cfDNA to detect antibody-mediated rejection (ABMR) primarily.

Table 2. Sensitivity and specificity of dd-cfDNA to detect graft rejection and/or damage.

| Name |

Organ(s) |

Sample Type |

Sensitivity (%) |

Specificity (%) |

| ] |

| Lung |

| Plasma |

| 55.6 |

| 75.8 |

| 43.3 |

| 83.6 |