Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Beatrix Zheng and Version 1 by Lanyue Zhang.

Zingiber striolatum Diels (Z. striolatum), a widely popular vegetable in China, is famous for its medicinal and nutritional values. However, the anti-inflammatory effects of essential oil from Z. striolatum (EOZS) remain unclear. This research unveils the antioxidant capability and potential molecular mechanism of EOZS in regulating inflammatory response, and suggests the application of EOZS as a natural antioxidant and anti-inflammatory agent in the pharmaceutical and functional food industries.

- Zingiber striolatum Diels

- essential oil

- oxidant stress

- anti-inflammatory activity

- MAPK

- NF-κB

1. Introduction

Inflammation, the basis of many kinds of pathological processes, is an automatic defense response of the human body. It is generally triggered by infection, tissue injury, tissue stress and malfunction [1]. The primary role of inflammation is to eliminate harmful stimuli, prevent further damage, start the healing process and recover the normal functions of injured tissues [2]. However, host tissue homeostasis will be disarranged or damaged when inflammation is excessive or uncontrolled [3], which may induce diseases such as acute cytokine storm [4], rheumatoid arthritis [5], atherosclerosis [6] and cancer. In dysregulated inflammatory response, macrophages are hyperactivated to induce oxidant stress and produce more inflammatory media such as reactive oxygen species (ROS), nitric oxide (NO), Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), Interleukin-6 (IL-6), Interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), thereby further aggravating the progression of inflammation [7][8]. The imbalance of oxidative stress caused by inflammation may also lead to disease exacerbations [9]. For example, the severity of COVID-19 patients is affected by oxidative stress [10]. Excessive NO and ROS will destroy lipids, proteins and DNA in cells, and damage the normal function of tissues [11][12]. In order to reduce the risk of inflammation-related diseases, it is of great significance to suppress dysregulated inflammatory response. Thus, the development of anti-inflammatory agents is still a common concern of many scientists.

In recent years, people have become more aware of the health benefits of natural products derived from fruits, vegetables or other plants, and have shown great interest in developing natural anti-inflammatory agents. Essential oil is a kind of volatile aromatic substance extracted from plants. As a kind of traditional medicine, essential oils have attracted widespread attention because of their potential pharmacological activities including anti-inflammatory, antioxidant [13], antibacterial [14] and anticancer potential [15], etc.

Zingiber striolatum Diels, commonly known as Yang-He in Chinese, belongs to Zingiber species. As a unique vegetable grown in China, the edible part of Z. striolatum is the flower. It is widely distributed and predominantly wild but less cultivated [16]. Z. striolatum possesses high nutritional value because it contains a variety of amino acids, proteins and rich cellulose [17]. The total amino acid content in Z. striolatum is 19.83%, of which essential amino acids account for 37.17% of the total amino acids [18]. A recent study has suggested that the ethanol extract from Z. striolatum exerted noticeable hypoglycemic activity in vitro [17]. Tian et al. revealed that the essential oil of Z. striolatum from the rhizome has weak antioxidant activity but strong antimicrobial and anticancer activities [19]. They further found that essential oils of Z. striolatum from flowers, leaves and stems showed significant cytotoxicity against K562, PC-3 and A549 cells [20]. According to the Compendium of Materia Medica, a famous Chinese medicine classic compiled by Shizhen Li during the 16th century, Z. striolatum was used for promoting blood circulation, eliminating phlegm, alleviating coughing and relieving swelling and pain, which means it has potential anti-inflammatory activity. However, the regulatory effect of Z. striolatum on inflammatory response and its molecular mechanism remain to be elucidated. Therefore, the aim of our study was to assess the anti-inflammatory activity of EOZS and explore its potential molecular mechanism in vitro and in vivo. To understand the material basis of EOZS, we also analyzed their chemical composition from different districts in China by GC–MS.

2. Current Insights

Natural products are used as traditional medicines for the treatment or prevention of a wide variety of human diseases due to their extensive pharmacological properties. As a kind of relatively safe natural product, plant-derived essential oils are more easily accepted by consumers [21]. To reduce substance abuse, the use of essential oils to relieve or treat diseases has also been developed as an alternative therapy [22]. Z. striolatum has traditional medicinal value, but the anti-inflammatory effect of its essential oil has not yet been reported. In the present work, we mainly analyzed the composition of EOZS from seven regions and evaluated their suppressive effect on inflammatory response and oxidant stress. Sixteen common chemical compounds were identified from the EOZS of seven regions, suggesting that these characteristic peaks may be used as the index components for quality control of Z. striolatum. From the phytochemical classification, Z. striolatum from seven locations could be divided into three clusters. The factors causing these differences may be related to the geographical location, climatic conditions and soil environment. Although the main chemical components and relative contents in S1–S5 were similar, the cytotoxicity of S1 was stronger than other samples. This indicated that it may be caused by minor or trace components in the S1.

Our research showed that EOZS from seven locations exhibited a certain degree of DPPH scavenging activity. Furthermore, they also significantly inhibited the production of NO and ROS in LPS-induced RAW 264.7 cells. Interestingly, EOZS from Huaihua City (S2), Zhangjiajie City (S4) and Enshi City (S5) showed a stronger inhibitory effect on NO production in LPS-induced RAW 264.7 cells. From the results of PCA and HCA, it can be seen that the main difference between cluster III (S1–S5) and other clusters included β-phellandrene, β-pinene, α-pinene and α-humulene. Lee et al. identified β-phellandrene as the main component of Zanthoxylum schinifolium essential oil, and found that Zanthoxylum schinifolium essential oil significantly inhibited the mRNA transcription level of inducible nitric oxide synthase [23]. There was direct evidence that α-pinene and α-humulene suppressed NO produced by activated macrophages or monocytes [24][25]. In addition, as the main component of the essential oil of Xylopia parviflora, β-pinene has been shown to reduce the NO production in LPS-induced RAW 264.7 cells [26]. The above evidence may partly explain the anti-inflammatory activity of S2, S4 and S5. S1 was not compared with other samples in cluster III at the same concentration because of its stronger cytotoxicity. However, the main components of S3 and S2, S4 and S5 were similar, whilst the effect of S3 was weaker, indicating that there may be an antagonistic effect between different components in S3.

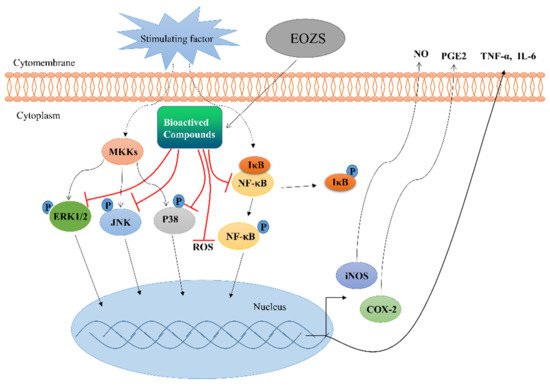

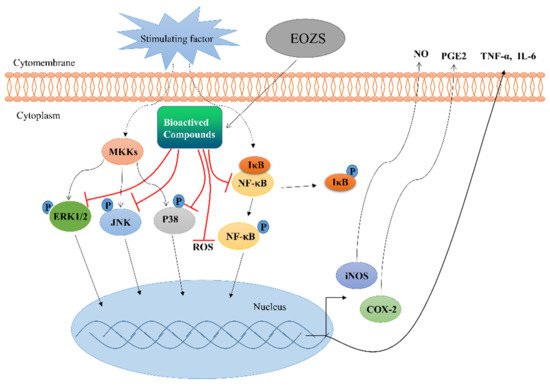

Transcriptomics is a method to study the expression of RNA and the regulation of transcription in cells [27]. In recent years, transcriptomics has been widely used to reveal differences in the expression of genes in biological functions and to discover the mechanisms or targets of drugs. By using transcriptomics analysis, Li et al. found that Rebaudioside A could protect Caenorhabditis elegans from oxidative stress via regulating TOR and PI3K/Akt pathways [28]. RNA sequencing results of this study indicated that the MAPK and NF-κB pathways may be involved in the potential anti-inflammatory mechanism of EOZS. The MAPK signaling pathway plays an important role in extracellular signaling to the inner nucleus, and it can be activated by external environmental stress or stimulation by inflammatory mediators [29]. It has been shown that the conditional knockdown of the p38α MAPK gene results in a significant reduction in TNF-α production by LPS-induced microglia in mice, thus preventing the neuronal damage produced by LPS induction [30]. NF-κB, as a core regulator of inflammatory response, has been a popular research target in the field of inflammation and immunity. When canonical NF-κB signaling pathway is activated, IκB is phosphorylated via the IκB kinase (IKK) complex and subsequently polyubiquitinated and degraded by the 26S proteasome. NF-κB is then phosphorylated and enters the nucleus, leading to the initiation and protein expression of pro-inflammatory genes such as TNF-α and IL-6 [31]. All of this evidence suggests that the activation status of MAPK and NF-κB signaling pathways has a critical impact on the production of downstream pro-inflammatory mediators. Therefore, the inhibition of the excessive activation of MAPK and NF-κB signaling pathways is a strategy for the treatment of inflammation-related diseases.

During inflammation, cells damaged by irritation recruit immune cells to migrate towards the site of inflammation by releasing cytokines and chemokines, while immune cells produce more inflammatory mediators through activated MAPK and NF-κB signaling pathways [32], creating a positive feedback loop that may further exacerbate the progression of inflammation. In this study, we demonstrated that EOZS inhibited the activation of macrophage and production of pro-inflammatory mediators through the regulation of MAPK and NF-κB signaling pathways (Figure 1). In vivo experiments also showed that EOZS could reduce the infiltration of immune cells to the site of inflammation to alleviate inflammation. Indeed, ample evidence suggests that plant volatile oils possess anti-inflammatory pharmacological activity in vivo and in vitro [33][34][35].

Figure 1. Schema showed the anti-inflammatory molecular mechanism of EOZS by activating MAPK and NF-κB signaling pathways.

3. Conclusions

In conclusion, this was the first study to clarify the anti-inflammatory molecular mechanism of EOZS, and these findings indicate that EOZS may have the potential to prevent or treat inflammation-related diseases. However, there are differences in the anti-inflammatory effects of EOZS from different locations. Therefore, it is necessary to establish relevant standards to control the quality of EOZS in order to promote its industrialization.

References

- Medzhitov, R. Origin and physiological roles of inflammation. Nature 2008, 454, 428–435.

- Nasef, N.A.; Mehta, S.; Ferguson, L.R. Susceptibility to chronic inflammation: An update. Arch. Toxicol. 2017, 91, 1131–1141.

- Duran, W.N.; Breslin, J.W.; Sanchez, F.A. The NO cascade, eNOS location, and microvascular permeability. Cardiovasc. Res. 2010, 87, 254–261.

- Fajgenbaum, D.C.; June, C.H. Cytokine storm. New Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 2255–2273.

- Chen, Z.; Bozec, A.; Ramming, A.; Schett, G. Anti-inflammatory and immune-regulatory cytokines in rheumatoid arthritis. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2019, 15, 9–17.

- Sorci-Thomas, M.G.; Thomas, M.J. Microdomains, inflammation, and atherosclerosis. Circ. Res. 2016, 118, 679–691.

- Abdulkhaleq, L.A.; Assi, M.A.; Abdullah, R.; Zamri-Saad, M.; Taufiq-Yap, Y.H.; Hezmee, M.N.M. The crucial roles of inflammatory mediators in inflammation: A review. Vet. World 2018, 11, 627.

- Hamidzadeh, K.; Christensen, S.M.; Dalby, E.; Chandrasekaran, P.; Mosser, D.M. Macrophages and the recovery from acute and chronic inflammation. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2017, 79, 567–592.

- Lv, H.; Yang, H.; Wang, Z.; Feng, H.; Deng, X.; Cheng, G.; Ci, X. Nrf2 signaling and autophagy are complementary in protecting lipopolysaccharide/d-galactosamine-induced acute liver injury by licochalcone A. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 1–15.

- Beltrán-García, J.; Osca-Verdegal, R.; Pallardó, F.V.; Ferreres, J.; Rodríguez, M.; Mulet, S.; Sanchis-Gomar, F.; Carbonell, N.; García-Giménez, J.L. Oxidative stress and inflammation in COVID-19-associated sepsis: The potential role of anti-oxidant therapy in avoiding disease progression. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 936.

- Deng, Y.; Matsui, Y.; Pan, W.; Li, Q.; Lai, Z. Yap1 plays a protective role in suppressing free fatty acid-induced apoptosis and promoting beta-cell survival. Protein Cell 2016, 7, 362–372.

- Taniguchi, A.; Tsuge, M.; Miyahara, N.; Tsukahara, H. Reactive oxygen species and antioxidative defense in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1537.

- Miguel, M.G. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities of essential oils: A short review. Molecules 2010, 15, 9252–9287.

- Freires, I.A.; Denny, C.; Benso, B.; De Alencar, S.M.; Rosalen, P.L. Antibacterial activity of essential oils and their isolated constituents against cariogenic bacteria: A systematic review. Molecules 2015, 20, 7329–7358.

- Bhalla, Y.; Gupta, V.K.; Jaitak, V. Anticancer activity of essential oils: A review. J. Sci. Food Agr. 2013, 93, 3643–3653.

- Huang, Z.; Xie, L.; Wang, H.; Zhong, J.; Li, Y.; Liu, J.; Ou, Z.; Liang, X.; Li, Y.; Huang, H.; et al. Geographic distribution and impacts of climate change on the suitable habitats of Zingiber species in China. Ind. Crop Prod. 2019, 138, 111429.

- Chen, T.; Cai, J.; Ni, J.; Yang, F. An UPLC-MS/MS application to investigate chemical compositions in the ethanol extract with hypoglycemic activity from Zingiber striolatum Diels. J. Chin. Pharm. Sci. 2016, 25, 116–121.

- Zhang, C.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, N.; Wang, J.; Li, W.; Zhou, D.; Zheng, X. Analysis of amino acid composition and evaluation of nutritional value of Zingiber strioatum Diels. J. Hubei Univ. Natl.-Nat. Sci. Ed. 2014, 32, 380–383.

- Tian, M.; Liu, T.; Wu, X.; Hong, Y.; Zhou, Y. Chemical composition, antioxidant, antimicrobial and anticancer activities of the essential oil from the rhizomes of Zingiber striolatum Diels. Nat. Prod. Res. 2020, 34, 2621–2625.

- Tian, M.; Hong, Y.; Wu, X.; Zhang, M.; Lin, B.; Zho, Y. Chemical constituents and cytotoxic activities of essential oils from the flowers, leaves and stems of Zingiber striolatum diels. Rec. Nat. Prod. 2020, 14, 144–149.

- Liu, C.; Zhang, R.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Q.; Cheng, A.; Guo, X.; Wang, X.; Sun, J. Supercritical CO2 fluid extraction of croton crassifolius Geisel root: Chemical composition and anti-proliferative, autophagic, apoptosis-inducing, and related molecular effects on A549 tumour cells. Phytomedicine 2019, 61, 152846.

- Leite, L.H.I.; Leite, G.O.; Silva, B.A.F.; Santos, S.A.A.R.; Magalhães, F.E.A.; Menezes, P.P.; Serafini, M.R.; Teixeira, C.S.; Brito, R.G.; Santos, P.L.; et al. Molecular mechanism underlying orofacial antinociceptive activity of Vanillosmopsis arborea Baker (Asteraceae) essential oil complexed with β-cyclodextrin. Phytomedicine 2019, 55, 293–301.

- Lee, J.; Chang, K.; Kim, G. Composition and anti-inflammatory activities of Zanthoxylum schinifolium essential oil: Suppression of inducible nitric oxide synthase, cyclooxygenase-2, cytokines and cellular adhesion. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2009, 89, 1762–1769.

- Rufino, A.; Ribeiro, M.; Judas, F.; Salgueiro, L.; Lopes, M.; Cavaleiro, C.; Mendes, A. Anti-inflammatory and chondroprotective activity of (+)-α-pinene: Structural and enantiomeric selectivity. J. Nat. Prod. 2014, 77, 264–269.

- Mazutti da Silva, S.M.; Rezende Costa, C.R.; Martins Gelfuso, G.; Silva Guerra, E.N. Wound healing effect of essential oil extracted from Eugenia dysenterica DC (Myrtaceae) leaves. Molecules 2019, 24, 2.

- Woguem, V.; Fogang, H.; Maggi, F.; Tapondjou, L.; Womeni, H.; Quassinti, L.; Bramucci, M.; Vitali, L.; Petrelli, D.; Lupidi, G.; et al. Volatile oil from striped African pepper (Xylopia parviflora, Annonaceae) possesses notable chemopreventive, anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial potential. Food Chem. 2014, 149, 183–189.

- Karkossa, I.; Raps, S.; Bergen, V.M.; Schubert, K. Systematic review of multi-omics approaches to investigate toxicological effects in macrophages. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 9371.

- Li, P.; Wang, Z.; Lam, S.M.; Shui, G. Rebaudioside A enhances resistance to oxidative stress and extends lifespan and healthspan in Caenorhabditis elegans. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 262.

- Hotamisligil, G.S.; Davis, R.J. Cell signaling and stress responses. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2016, 8, a006072.

- Xing, B.; Bachstetter, A.D.; Van Eldik, L.J. Microglial p38α MAPK is critical for LPS-induced neuron degeneration, through a mechanism involving TNFα. Mol. Neurodegener. 2011, 6, 1–12.

- Kawai, T.; Akira, S. Signaling to NF-κB by Toll-like receptors. Trends Mol. Med. 2007, 13, 460–469.

- Turner, M.D.; Nedjai, B.; Hurst, T.; Pennington, D.J. Cytokines and chemokines: At the crossroads of cell signalling and inflammatory disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 2014, 1843, 2563–2582.

- Polednik, K.M.; Koch, A.C.; Felzien, L.K. Effects of essential oil from Thymus vulgaris on viability and inflammation in zebrafish embryos. Zebrafish 2018, 15, 361–371.

- Rao, Z.; Xu, F.; Wen, T.; Wang, F.; Sang, W.; Zeng, N. Protective effects of essential oils from Rimulus cinnamon on endotoxin poisoning mice. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 101, 304–310.

- Wang, H.; Song, L.; Ju, W.; Wang, X.; Dong, L.; Zhang, Y.; Ya, P.; Yang, C.; Li, F. The acute airway inflammation induced by PM 2.5 exposure and the treatment of essential oils in Balb/c mice. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 44256.

More