Precision oncology aims to define the best treatment for each individual tumor by matching targeted drugs to the molecular alterations present in the tumor. This task is hampered by the complexity and heterogeneity of the molecular alterations present in each tumor and the resulting variability of patient’s responses. Systems biology allows us to reconstruct the complex behavior of biological systems and to compute the system's response to environmental perturbations, including targeted therapies. This helps to dissect drug resistance phenomena and to establish the best drug combinations for a specific, individual tumor.

- cancer systems biology

- statistical methods

- network analysis

- mathematical models

- signaling networks

- drug resistance

- patient-specific network modeling

- precision oncology

1. The challenges of precision oncology

Over the past decades, two key advances have changed the landscape of cancer research: a predominantly reductionist approach has given way to the widespread use of omics techniques [1][2][3], while the therapeutic armamentarium, previously based on chemotherapy and few hormonal drugs, has been enriched with a large variety of targeted drugs (drugs whose molecular targets are precisely defined [4]), affecting cancer intracellular signaling or the microenvironment and immune system.

Complexity [5] and heterogeneity [6] of tumors has prompted the development of precision oncology, aiming to tailor treatments to individual patients [7][8] by matching targeted drugs to the molecular alterations that are present in individual tumors. This requires a deep biological characterization of tumors, including omics studies. A fundamental objective is predicting the individual response to treatments, relying on the presence of the target (often a mutant, overexpressed, or fusion protein), but also on predictors formed by panels of biomarkers [9]. Another key objective is deciphering the mechanisms of resistance to targeted drugs, such as alterations in the target itself (e.g., secondary mutations), mutations in molecules downstream of the target, and network adaptation mechanisms, including facilitation of resistance by kinase dimerization and feedback mechanisms [10][11][12] or activation of parallel pathways [13]. A further objective is to identify optimal drug combinations that increase efficacy and overcome resistance [14].

The complexity of intracellular signaling and cell-cell interactions makes it particularly challenging to pursue these objectives. Here we review current systems biology methods and provide examples of how they can be valuable tools to tackle this task.

2. Systems Biology

Systems biology studies the collective behavior of different types of molecules involved in a biological process, aiming to reconstruct the system behavior. Systems of many different molecules have behaviors that cannot be simply deduced from the properties of their constitutive elements, and are characterized by “emergent properties” [15][16][17][18].

Biological entities are dynamical systems, that evolve in space and time. A snapshot of the system at a certain time point, showing the spatial disposition and the concentrations of molecules, is called a state. The system evolution through different states can be represented graphically as a trajectory in the so-called state space. The aim of systems analysis is to describe the evolution of the system following a perturbation, such as drug treatment.

Dynamical systems evolve towards specific states, called attractors. These may be fixed, steady states, or cyclic trajectories subtending oscillating behaviors, or irregular chaotic trajectories. A system can have more than one attractor, e.g., two different stable steady states (bistability), and evolve toward one or the other depending on the starting state of the system.

Typical emergent properties of dynamical systems are robustness, i.e., the ability to maintain their functions despite perturbations, and adaptation, i.e., the ability to adjust their behavior in response to environmental changes. Robustness and adaptation characterize tumors as complex systems, which almost inevitably adapt to anticancer drugs and develop resistance.

An array of statistical and mathematical modeling techniques can be applied to describe, with different levels of accuracy, dynamical biological processes [19].

3. Statistical Methods

Statistical models aim to find associations among variables. Supervised methods deal with different predefined classes of objects (e.g., responders versus non-responders) and try to identify a set of variable values that help us discriminate among classes. Unsupervised methods consider the whole set of data without prior classification and aim to identify intrinsic subsets in the data. Supervised methods include the different types of regression models: linear, logistic, Cox proportional hazards, as well as the so called robust regressions. Unsupervised methods include cluster analysis, aiming to identify relevant subsets in a dataset, and principal component analysis, pointing to reduce the number of variables by combining original variables into a few new, condensed variables. Partial least squares regression makes such variable reduction in a supervised context [20].

Machine learning is the part of artificial intelligence (AI) that uses computer algorithms to analyze big datasets to generate predictive models. These algorithms employ statistical tools, both supervised and unsupervised, and are capable to iteratively self-adjust to optimize the performance [21].

4. Network Analysis

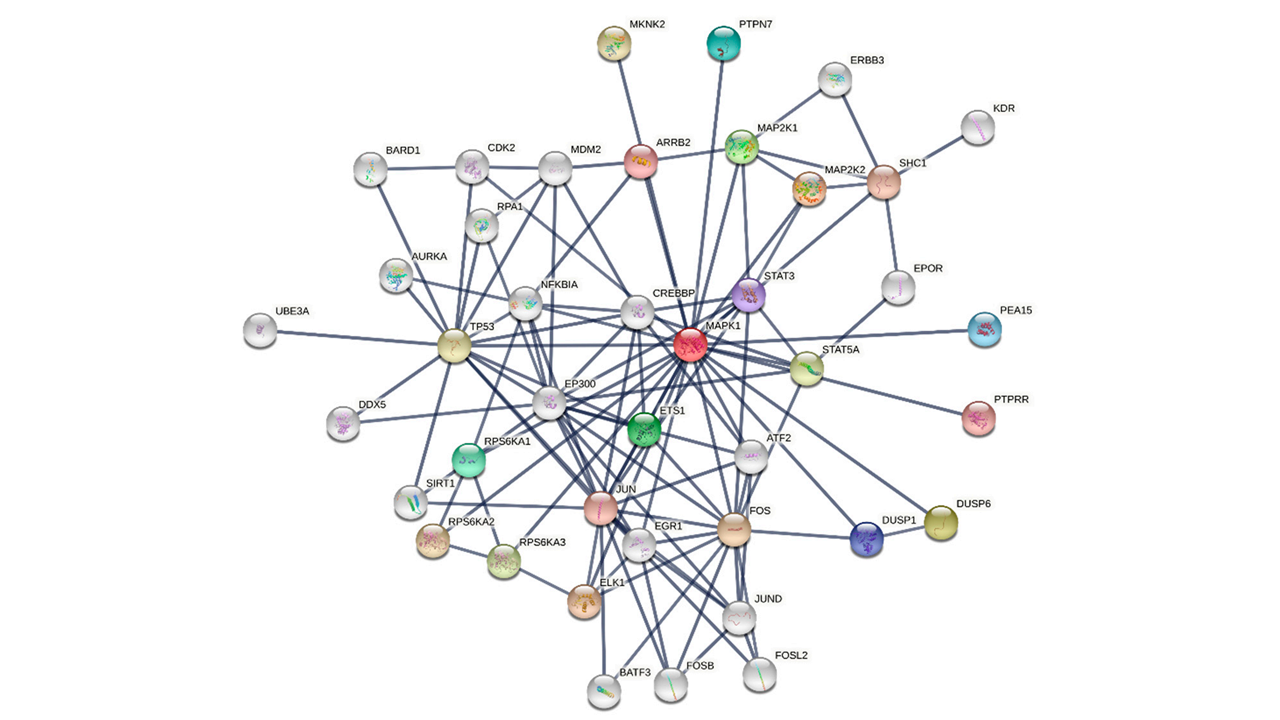

Another tool to decipher high throughput data is reconstructing networks of interconnected molecules, such as gene and protein networks [22] (Figure 1). Network analysis aims first to define the structure or topology of a network, which is linked to its functional properties.

Figure 1. Interaction network of MAPK1. The network is built using the STRING database [23]. The top 20 first neighbours and top 20 second neighbours of MAPK1 (aka ERK1) are shown.

Biological networks can be reconstructed following a "bottom-up" (or knowledge-based) approach, whereby the selection of molecules and interactions to be included in the network is based on information extracted from the literature and public databases. Alternatively, a top-down (or data-driven) approach can be followed, reconstructing the network directly from experimental data, for example from omics studies, a process called reverse engineering [24]. Different tools are used to reconstruct the interactions among molecules, including statistical tools in Bayesian networks, tools from information theory, or dynamical system-based approaches such as modular response analysis [25].

5. Logic Models

Logic models represent the interaction between two molecules as a logical statement [26]. In Boolean logic, each molecular species can be in one of two possible states (true or false, on or off, 1 or 0). A Boolean network is formed by a set of Boolean variables, where the connections among variables are defined by Boolean functions. The latter are represented by couples of attributes, specifying the states of the two variables. An activating signal may be represented as 1/1, meaning that when the first node is activated (1, on), also the second becomes activated. An inhibitory signal may be represented as 1/0, meaning that when the first node is activated, the second is inhibited (0, off). Logic modeling does not require knowledge of the detailed mechanistic relationship between nodes, but simply represents the direction and the type (e.g., activating or inhibitory) of relationship. Although logic models mainly yield qualitative results, they can reproduce the evolution of a system. They are suitable to predict the effects of perturbations, such as mutations or exposure to drugs, on a system’s behavior.

6. Mechanistic Models

Mechanistic models that are based on systems of differential equations require a more detailed knowledge of the biological process studied. Building such models requires (i) establishing which molecules and interactions to consider, (ii) choosing mathematical equations to describe each interaction, (iii) finding suitable values for the parameters involved, and then (iv) solving the equations to simulate the behavior of the system, making predictions about system responses to perturbations [16][26].

The simplest form of differential equations are ordinary differential equations (ODEs), which use the mean field approximation and are suitable when the number of molecules of each species is large. Modeling biological systems with ODEs involves considering all the processes that modify the level or activity of each relevant molecule. These processes are characterized by rate parameters, such as kinetic constants, whose values must be measured or estimated experimentally. Solutions to ODEs are functions of time, represented as plots on Cartesian axes depicting the evolution of the state of the system over time.

If the assumption of high molecule numbers (more than 1000) is not fulfilled, stochastic differential equations must be used, which consider a probability distribution, instead of a numeric value, for each variable [27].

A precise mechanistic modeling requires to represent each different state of any single molecule as an individual variable. Often protein molecules have multiple interacting domains and phosphorylation states, which leads to an exponential increase in the number of variables and ODEs. To overcome this issue, the approach of rule-based modeling has been developed [28].

7. Emerging Network Properties Captured by Differential Equation Models

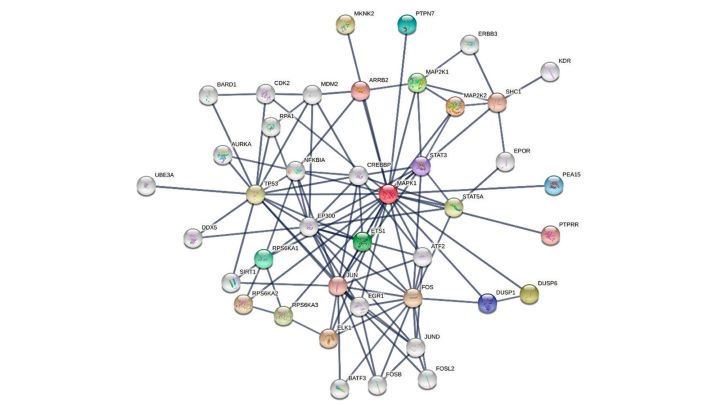

Signal transduction in most cellular networks occurs via cascades of protein phosphorylation-dephosphorylation cycles (Figure 2A), controlled by opposing enzymes, a protein kinase and a phosphatase (Figure 2B,C). These cycles show peculiar behaviors like ultrasensitivity, whereby, when the converting enzymes operate near saturation, the response to an input becomes abrupt [29].

Figure 2. A cascade of protein phosphorylation-dephosphorylation cycles.

A cascade of protein phosphorylation-dephosphorylation cycles.

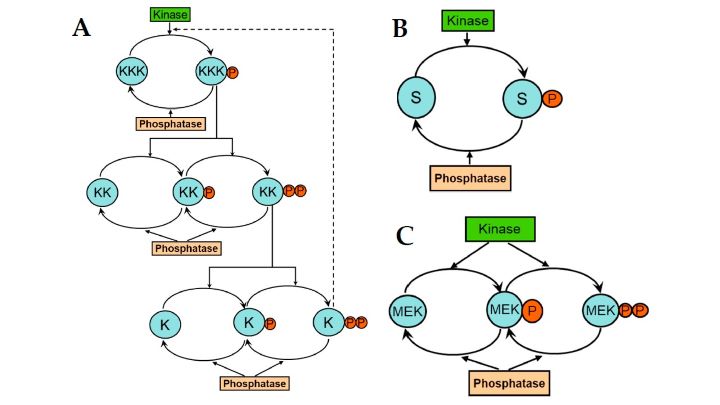

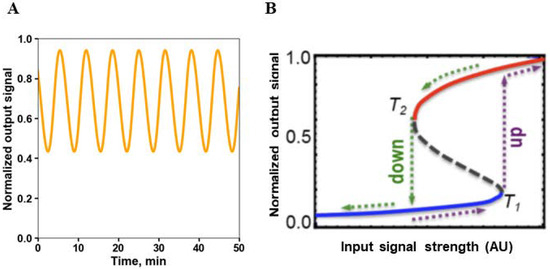

A fundamental feature of networks are feedback loops. Positive feedbacks amplify the signal, whereas negative feedbacks attenuate it. But feedbacks can also favor the occurrence of instabilities, leading to a radical change in the state of the system, known as bifurcations [14]. Too strong, long negative feedbacks induce damped or sustained oscillations [30] (Figure 3A). Positive feedbacks can cause bistability and hysteresis, where the threshold for jumping from one steady state to the other differs depending on the direction of change of an external signal or parameter (Figure 3B). Hysteresis prevents the easy reversal of a system state, committing to its sustainability. Positive feedbacks occurring in combination with negative feedbacks can give rise to sustained oscillations, called relaxation oscillations, typically observed in cell cycle regulation [31].

|

Figure 3. Oscillations and hysteresis brought about by negative and positive feedback loops.

Under some conditions, hysteresis gives way to an irreversible switch to one of the two steady states [32]. Hysteresis and irreversible switches allow the control of multiple irreversible transitions in cellular processes, such as those occurring at cell cycle checkpoints.

8. Modeling Spatiotemporal Network Behavior by Partial Differential Equations

The use of ODE models requires the fulfillment of the assumptions that the molecules are evenly distributed in the modeled compartment, and this condition is not fulfilled for molecules bound to membranes or molecular scaffolds. Often, opposing enzymes, such as a kinase and phosphatase in signal transduction cascades, are localized to different cellular compartments (e.g. a kinase resides at the cell membrane, whereas a phosphatase is homogeneously distributed in the cytosol). This results in the emergence of gradients of phosphorylated and unphosphorylated forms of the protein substrate. Because in this and similar cases, the variables (concentrations) depend not only on time but also on the spatial coordinates, describing the rate of change of these concentrations requires the so called “partial differential equations” (PDEs), which model the spatiotemporal behavior of molecular species. Recently these have been used to model how the biochemical machinery of RhoA GTPase govern cell movements, faithfully reproducing the cellular behavior observed in in vitro experiments [33].

9. Mechanistic Models Help Us Understand Resistance to Targeted Therapies

Cellular network adaptations are involved in the development of resistance to targeted therapies. A classic example is resistance to BRAF inhibitors in patients with melanoma. BRAF inhibitors induce conformational changes in BRAF, favoring the formation of RAF homo- and hetero-dimers. If only one RAF protomer is inhibited in a RAF-dimer, the inhibited protomer allosterically activates the other RAF protomer, leading to paradoxical activation of the downstream MAPK pathway. Dynamical models suggest that upon RAF dimerization, for thermodynamic reasons, the affinity of a BRAF inhibitor for one of the RAF protomers increases, but the affinity for the other protomer sharply decreases. This favors the formation of RAF dimers where only one protomer is bound to the inhibitor, with consequent allosteric activation of the inhibitor-free protomer and sustained MAPK signaling activity [11][34]. These models predict that a combination of two structurally different inhibitors, binding to different RAF conformations, can overcome resistance, and allow to estimate the levels of synergy or antagonism between RAF inhibitors and MEK inhibitors. These predictions were confirmed with experiments in tumor cell lines [12].

Negative feedbacks have been held responsible for the development of acquired resistance to many targeted drugs. Yet, a systematic analysis of network adaptation mechanisms [12] shows that, following drug inhibition, negative feedbacks can lead to a transient reactivation or overshoot but cannot fully restore output signaling (Figure 4A,B). Rather, this work highlights three ways in which treatment with a targeted inhibitor can be followed by a complete recovery of pathway signaling: (i) when there are at least two connection routes, activating and inhibitory, from an inhibited upstream drug target to the downstream output, creating a feedforward loop in addition to the other connection route; (ii) when there is a crosstalk among two pathways, whereby inhibition of one of them can favor the activation of the other; (iii) when a kinase inhibitor induces kinase dimerization, as described above for RAF inhibitors [12]. Combined with kinase dimerization, negative feedbacks facilitate drug resistances.

10. Signaling Network Models Can Predict Drug Sensitivity

Modeling the dynamics of signaling pathways to drug perturbations can predict cell type–specific responses to small-molecule therapeutics and prioritize primary drug targets and their combinations. Dynamic logic models of signaling networks were built for colorectal cancer cell lines based on a large-scale signaling perturbation screening [35]. Simulated signaling dynamics correlated with some drug sensitivities, and a drug combination predicted to overcome resistance to MEK inhibitors by co-blockade of GSK3 was validated experimentally. A dynamic model of the estrogen receptor-induced proliferation of MCF-7 breast cancer cells was built to predict responses to endocrine therapy [36]. This ODE model was able to predict the responses to a combination treatment of estrogen deprivation and the drug palbociclib inhibiting Cdk4/6. Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) greatly enhanced cancer treatment, yet many patients are intrinsically resistant to anti-programmed cell death protein 1 (anti-PD1) and anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (anti-CTLA4) therapies or they become resistant after initial response. A logic network model encompassing PD1, CTLA4 and other inhibiting and activating checkpoints [37] was able to recapitulate results of existing experimental studies of anti-PD1 and anti-CTLA4 therapies, and suggested the best combinations of ICIs with drugs targeting other checkpoints.

11. Patient-Specific Network Modeling

Models can be used to carry out patient-specific network simulations and to construct patient-specific dynamic biomarkers. For this purpose, variables such as the amounts, mutational status and copy number variation of relevant molecular species are measured directly on a patient tumor sample and the values are entered into the model, to perform patient-specific simulations of the system behavior.

Several studies have exploited systems-level models of apoptosis to predict the patient responses to chemotherapy. Patient-specific ODEs-based models of the intrinsic apoptotic pathway, based on the concentrations of five key molecules determined in samples of colorectal tumors, were the only significant predictor of patient outcome at multivariate analysis and outperformed predictors based on statistical analyses of apoptotic molecules [38]. A logic model of the intrinsic and extrinsic apoptosis pathways was used to simulate the apoptotic response to different drugs or drug combinations in pancreatic tumor samples and cell lines, allowing to predict effective drug combinations that were confirmed experimentally [39].

Other studies have been performed to define the best combination therapy according to the set of driver genes of an individual tumor [40], to reconstruct metabolic networks [41] and to investigate the metabolic differences subtending different tumor phenotypes, such as resistance or sensitivity to radiation therapy [42].

The c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) pathway is a MAPK cascade mediating apoptosis in response to different types of stress, including chemotherapeutic agents. JNK may undergo either a gradual activation in response to growth factors, promoting cell survival and proliferation, or an ultrasensitive, switch-like activation in response to stress, leading to apoptosis. Reconstruction of the JNK pathway in neuroblastoma cell lines identified a positive feedback from JNK to MKK7 as responsible for the ultrasensitive switch-like apoptotic response [43]. Patient-specific simulations obtained by an ODEs-based model of JNK pathway showed that JNK response is increasingly impaired with increasing stage of the disease and has independent prognostic value in multivariate analysis [43].

12. Conclusions

Despite major advances, cancer treatment remains an open challenge in many respects. Identifying the driver molecular alterations in a tumor is only part of the solution [44], and to obtain long-term control, or even cure, of complex tumors will likely require that (i) their key molecular alterations are correctly targeted, and (ii) network adaptations causing drug resistance are prevented by properly designated drug combinations. Describing and analyzing the intrinsic behavior of the biological processes that underlie tumor pathology, dynamical models will potentially allow to identify the key points for effective interventions with target drugs, substantially delaying or preventing resistance.

References

- The ICGC/TCGA Pan-Cancer Analysis of Whole Genomes Consortium; Pan-cancer analysis of whole genomes. Nature 2020, 578, 82-93, 10.1038/s41586-020-1969-6.

- Apostolia M. Tsimberidou; Elena Fountzilas; Leonidas Bleris; Razelle Kurzrock; Transcriptomics and solid tumors: The next frontier in precision cancer medicine. Seminars in Cancer Biology 2020, Sep 17, S1044-579X(20)30196-6, 10.1016/j.semcancer.2020.09.007.

- Walter Kolch; Andrew Pitt; Functional proteomics to dissect tyrosine kinase signalling pathways in cancer. Nature Cancer 2010, 10, 618-629, 10.1038/nrc2900.

- Yeuan Ting Lee; Yi Jer Tan; Chern Ein Oon; Molecular targeted therapy: Treating cancer with specificity. European Journal of Pharmacology 2018, 834, 188-196, 10.1016/j.ejphar.2018.07.034.

- Douglas Hanahan; Robert A. Weinberg; Hallmarks of Cancer: The Next Generation. Cell 2011, 144, 646-674, 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013.

- Michalina Janiszewska; The microcosmos of intratumor heterogeneity: the space-time of cancer evolution. Oncogene 2019, 39, 2031-2039, 10.1038/s41388-019-1127-5.

- L.R. Yates; Joan Seoane; C. Le Tourneau; L.L. Siu; R. Marais; Stefan Michiels; J.C. Soria; P. Campbell; Nicola Normanno; A. Scarpa; et al.J.S. Reis-FilhoJ. RodonC. SwantonFabrice Andre The European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) Precision Medicine Glossary. Annals of Oncology 2017, 29, 30-35, 10.1093/annonc/mdx707.

- Jeffrey Abrams; Barbara Conley; Margaret Mooney; James Zwiebel; Alice Chen; John J. Welch; Naoko Takebe; Shakun Malik; Lisa McShane; Edward Korn; et al.Mickey WilliamsLouis StaudtJames H Doroshow National Cancer Institute's Precision Medicine Initiatives for the New National Clinical Trials Network. American Society of Clinical Oncology Educational Book 2014, 34, 71-76, 10.14694/edbook_am.2014.34.71.

- Fabrice Andre; Nofisat Ismaila; N. Lynn Henry; Mark R. Somerfield; Robert C. Bast; William Barlow; Deborah E. Collyar; M. Elizabeth Hammond; Nicole M. Kuderer; Minetta C. Liu; et al.Catherine Van PoznakAntonio C. WolffVered Stearns Use of Biomarkers to Guide Decisions on Adjuvant Systemic Therapy for Women With Early-Stage Invasive Breast Cancer: ASCO Clinical Practice Guideline Update—Integration of Results From TAILORx. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2019, 37, 1956-1964, 10.1200/jco.19.00945.

- David Lake; Sonia A. L. Corrêa; Jürgen Müller; Negative feedback regulation of the ERK1/2 MAPK pathway. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 2016, 73, 4397-4413, 10.1007/s00018-016-2297-8.

- Boris N. Kholodenko; Drug Resistance Resulting from Kinase Dimerization Is Rationalized by Thermodynamic Factors Describing Allosteric Inhibitor Effects. Cell Reports 2015, 12, 1939-1949, 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.08.014.

- Boris N. Kholodenko; Nora Rauch; Walter Kolch; Oleksii S. Rukhlenko; A systematic analysis of signaling reactivation and drug resistance. Cell Reports 2021, 35, 109157-109157, 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109157.

- Ayesha Murtuza; Ajaz Bulbul; John Paul Shen; Parissa Keshavarzian; Brian D. Woodward; Fernando J. Lopez-Diaz; Scott M. Lippman; Hatim Husain; Novel Third-Generation EGFR Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors and Strategies to Overcome Therapeutic Resistance in Lung Cancer. Cancer Research 2019, 79, 689-698, 10.1158/0008-5472.can-18-1281.

- Sandra M. Swain; José Baselga; Sung-Bae Kim; Jungsil Ro; Vladimir Semiglazov; Mario Campone; Eva Ciruelos; Jean-Marc Ferrero; Andreas Schneeweiss; Sarah Heeson; et al.Emma ClarkGraham RossMark C. BenyunesJavier Cortés Pertuzumab, Trastuzumab, and Docetaxel in HER2-Positive Metastatic Breast Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine 2015, 372, 724-734, 10.1056/nejmoa1413513.

- Upinder S. Bhalla; Ravi Iyengar; Emergent Properties of Networks of Biological Signaling Pathways. Science 1999, 283, 381-387, 10.1126/science.283.5400.381.

- Boris N. Kholodenko; Cell-signalling dynamics in time and space. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 2006, 7, 165-176, 10.1038/nrm1838.

- Boris N. Kholodenko; John Hancock; Walter Kolch; Signalling ballet in space and time. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 2010, 11, 414-426, 10.1038/nrm2901.

- Walter Kolch; Melinda Halasz; Marina Granovskaya; Boris Kholodenko; The dynamic control of signal transduction networks in cancer cells. Nature Cancer 2015, 15, 515-527, 10.1038/nrc3983.

- Iman Tavassoly; Joseph Goldfarb; Ravi Iyengar; Systems biology primer: the basic methods and approaches. Essays in Biochemistry 2018, 62, 487-500, 10.1042/ebc20180003.

- Kevin A. Janes; Michael B. Yaffe; Data-driven modelling of signal-transduction networks. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 2006, 7, 820-828, 10.1038/nrm2041.

- Bhavneet Bhinder; Coryandar Gilvary; Neel S. Madhukar; Olivier Elemento; Artificial Intelligence in Cancer Research and Precision Medicine. Cancer Discovery 2021, 11, 900-915, 10.1158/2159-8290.cd-21-0090.

- Enrico Pieroni; Sergio De La Fuente Van Bentem; Gianmaria Mancosu; Enrico Capobianco; Heribert Hirt; Alberto De La Fuente; Protein networking: insights into global functional organization of proteomes. PROTEOMICS 2008, 8, 799-816, 10.1002/pmic.200700767.

- Damian Szklarczyk; Annika L Gable; Katerina C Nastou; David Lyon; Rebecca Kirsch; Sampo Pyysalo; Nadezhda T Doncheva; Marc Legeay; Tao Fang; Peer Bork; et al.Lars J JensenChristian von Mering The STRING database in 2021: customizable protein–protein networks, and functional characterization of user-uploaded gene/measurement sets. Nucleic Acids Research 2020, 49, D605-D612, 10.1093/nar/gkaa1074.

- Gustavo Stolovitzky; Don Monroe; Andrea Califano; Dialogue on Reverse-Engineering Assessment and Methods: The DREAM of High-Throughput Pathway Inference. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 2007, 1115, 1-22, 10.1196/annals.1407.021.

- Frank J. Bruggeman; Hans V. Westerhoff; Jan B. Hoek; Boris N. Kholodenko; Modular Response Analysis of Cellular Regulatory Networks. Journal of Theoretical Biology 2002, 218, 507-520, 10.1016/s0022-5193(02)93096-1.

- Nicolas Le Novère; Quantitative and logic modelling of molecular and gene networks. Nature Reviews Genetics 2015, 16, 146-158, 10.1038/nrg3885.

- Daniel T. Gillespie; Stochastic Simulation of Chemical Kinetics. Annual Review of Physical Chemistry 2007, 58, 35-55, 10.1146/annurev.physchem.58.032806.104637.

- Michael Blinov; James Faeder; Byron Goldstein; William S. Hlavacek; BioNetGen: software for rule-based modeling of signal transduction based on the interactions of molecular domains. Bioinformatics 2004, 20, 3289-3291, 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth378.

- Boris Kholodenko; Jan Hoek; Hans Westerhoff; Guy C. Brown; Quantification of information transfer via cellular signal transduction pathways. FEBS Letters 1997, 414, 430-434, 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01018-1.

- Boris N. Kholodenko; Negative feedback and ultrasensitivity can bring about oscillations in the mitogen-activated protein kinase cascades. JBIC Journal of Biological Inorganic Chemistry 2000, 267, 1583-1588, 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01197.x.

- Novak, B., & Tyson, J. J.; Numerical analysis of a comprehensive model of M-phase control in Xenopus oocyte extracts and intact embryos. Journal of cell science 1993, 106, 1153-1168.

- Wen Xiong; James E. Ferrell; A positive-feedback-based bistable ‘memory module’ that governs a cell fate decision. Nature 2003, 426, 460-465, 10.1038/nature02089.

- Alfonso Bolado-Carrancio; Oleksii S Rukhlenko; Elena Nikonova; Mikhail A Tsyganov; Anne Wheeler; Amaya Garcia-Munoz; Walter Kolch; Alex von Kriegsheim; Boris N Kholodenko; Periodic propagating waves coordinate RhoGTPase network dynamics at the leading and trailing edges during cell migration. eLife 2020, 9, 1–34, 10.7554/elife.58165.

- Oleksii S. Rukhlenko; Fahimeh Khorsand; Aleksandar Krstic; Jan Rozanc; Leonidas G. Alexopoulos; Nora Rauch; Keesha E. Erickson; William S. Hlavacek; Richard G. Posner; Silvia Gómez-Coca; et al.Edina RostaCheree FitzgibbonDavid MatallanasJens RauchWalter KolchBoris N. Kholodenko Dissecting RAF Inhibitor Resistance by Structure-based Modeling Reveals Ways to Overcome Oncogenic RAS Signaling. Cell Systems 2018, 7, 161-179.e14, 10.1016/j.cels.2018.06.002.

- Federica Eduati; Victoria Doldàn-Martelli; Bertram Klinger; Thomas Cokelaer; Anja Sieber; Fiona Kogera; Mathurin Dorel; Mathew J. Garnett; Nils Blüthgen; Julio Saez-Rodriguez; et al. Drug Resistance Mechanisms in Colorectal Cancer Dissected with Cell Type–Specific Dynamic Logic Models. Cancer Research 2017, 77, 3364-3375, 10.1158/0008-5472.can-17-0078.

- Wei He; Diane M. Demas; Isabel P. Conde; Ayesha N. Shajahan-Haq; William T. Baumann; Mathematical modelling of breast cancer cells in response to endocrine therapy and Cdk4/6 inhibition. Journal of The Royal Society Interface 2020, 17, 20200339, 10.1098/rsif.2020.0339.

- Maria Kondratova; Emmanuel Barillot; Andrei Zinovyev; Laurence Calzone; Modelling of Immune Checkpoint Network Explains Synergistic Effects of Combined Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy and the Impact of Cytokines in Patient Response. Cancers 2020, 12, 3600, 10.3390/cancers12123600.

- Andreas Lindner; Caoimhín G. Concannon; Gerhardt J. Boukes; Mary D. Cannon; Fabien Llambi; Deborah Ryan; Karen Boland; Joan Kehoe; Deborah A. McNamara; Frank Murray; et al.Elaine W. KaySuzanne HectorDouglas GreenHeinrich J. HuberJochen Prehn Systems Analysis of BCL2 Protein Family Interactions Establishes a Model to Predict Responses to Chemotherapy. Cancer Research 2013, 73, 519-528, 10.1158/0008-5472.can-12-2269.

- Jorge Gómez Tejeda Zañudo; Steven Steinway; Réka Albert; Discrete dynamic network modeling of oncogenic signaling: Mechanistic insights for personalized treatment of cancer. Current Opinion in Systems Biology 2018, 9, 1-10, 10.1016/j.coisb.2018.02.002.

- Wei-Feng Guo; Shao-Wu Zhang; Yue-Hua Feng; Jing Liang; Tao Zeng; Luonan Chen; Network controllability-based algorithm to target personalized driver genes for discovering combinatorial drugs of individual patients. Nucleic Acids Research 2021, 49, e37-e37, 10.1093/nar/gkaa1272.

- Aarash Bordbar; Douglas McCloskey; Daniel C. Zielinski; Nikolaus Sonnenschein; Neema Jamshidi; Bernhard O. Palsson; Personalized Whole-Cell Kinetic Models of Metabolism for Discovery in Genomics and Pharmacodynamics. Cell Systems 2015, 1, 283-292, 10.1016/j.cels.2015.10.003.

- Joshua Lewis; Tom E. Forshaw; David A. Boothman; Cristina M. Furdui; Melissa L. Kemp; Personalized Genome-Scale Metabolic Models Identify Targets of Redox Metabolism in Radiation-Resistant Tumors. Cell Systems 2021, 12, 68-81.e11, 10.1016/j.cels.2020.12.001.

- Dirk Fey; Melinda Halasz; Daniel Dreidax; Sean P. Kennedy; Jordan F. Hastings; Nora Rauch; Amaya Garcia Munoz; Ruth Pilkington; Matthias Fischer; Frank Westermann; et al.Walter KolchBoris N. KholodenkoDavid R. Croucher Signaling pathway models as biomarkers: Patient-specific simulations of JNK activity predict the survival of neuroblastoma patients. Science Signaling 2015, 8, ra130-ra130, 10.1126/scisignal.aab0990.

- Matthew H. Bailey; Collin Tokheim; Eduard Porta-Pardo; Sohini Sengupta; Denis Bertrand; Amila Weerasinghe; Antonio Colaprico; Michael C. Wendl; Jaegil Kim; Brendan Reardon; et al.Patrick Kwok-Shing NgKang Jin JeongSong CaoZixing WangJianjiong GaoQingsong GaoFang WangEric Minwei LiuLoris MularoniCarlota Rubio-PerezNiranjan NagarajanIsidro Cortés-CirianoDaniel Cui ZhouWen-Wei LiangJulian M. HessVenkata D YellapantulaDavid TamboreroAbel Gonzalez-PerezChayaporn SuphavilaiJia Yu KoEkta KhuranaPeter J. ParkEliezer M. Van AllenHan LiangMC3 Working GroupCancer Genome Atlas Research NetworkMichael S LawrenceAdam GodzikNuria Lopez-BigasJosh StuartDavid WheelerGad GetzKen ChenAlexander J. LazarGordon B. MillsRachel KarchinLi Ding. Comprehensive Characterization of Cancer Driver Genes and Mutations. Cell 2018, 173, 371-385.e18, 10.1016/j.cell.2018.02.060.