Touristic destinations all around the world are struggling to digitally transform the touristic experience and the touristic products they offer and to capitalize a good experience with new tourists and returning ones. It is possible for various lines of business to come together and work along one another for an improve touristic experience using mobile technologies in a personalized, targeted approach.

- digital memento

- digital souvenir

- e-memento

- e-souvenir

1. Introduction

2. Designing a Digital Memento

A digital memento that will serve as a dynamic postcard of the personalized experience in the routes and visits taking place while in vacations is proposed. The visitors are usually taking picture along routes they may follow that later need further organization and processing. The solution was designed and implemented contributing the following to the industry:

-

Guided process to assist users in taking a photograph (e.g., selfie) while on a trip;

-

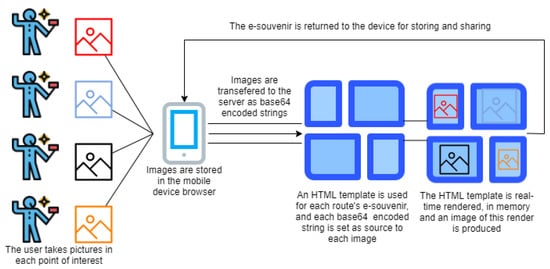

Automatic creation of an e-souvenir [4], a collage of landscape and selfie photos, provided as a digital cart-postal;

-

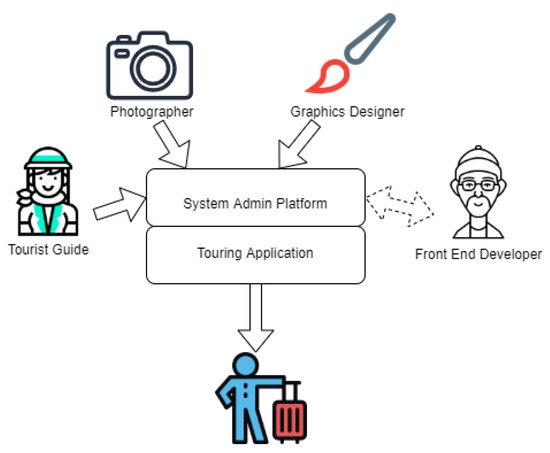

An open platform that gives the photographers and graphic designers the means to express themselves and create cart-postal images that will later be personalized for a user;

-

An ecosystem for digital organization of memories that accompanies self-guided tour apps.

3. Related Work

3.1. Touristic Memorable Experience

3.2. Personalized Printed Posters and Media Package Souvenir Appification

Sakkopoulos et al. [4], in 2005, presented how appification had been introduced to describe the rapidly widening shift from web browsing to the usage of smartphone apps for Internet-based information access and e-services consumption. This work showed how user involvement can be increased when, instead of buying a physical souvenir from a museum, a personalized e-souvenir [4] can be formed and acquired by the user combining ready-made photos and videos into a single multimedia package. This is the first time that the user intervened into forming a representation of their own memories into a digital token. However, no further personalisation has been included. It is also shown how QoS assurance techniques enable efficient media delivery through smartphones to assist making the old-fashioned shopping souvenirs go online and become virtual. Kunieda et al. [15][13] presented a way of how collaboration of various sectors, institutes and organizations could produce a regional problem-solving information system through an agile development process model. They addressed problems such as local advertisements (with KadaPos), travel diaries (with KaDiary) and tourist guidebooks (with KadaPam). All three solutions offered a personalized information brochure printed out for each problem. So, the person interested in the solution could reach a predefined physical printing system and receive the aforementioned brochure. In this case, personalisation has been used to produce a final printed product—a map—and no digital transformation is employed at the end-users’ hands but only for the backend.4. Solution Architecture

4.1. User Experience—Top Tier

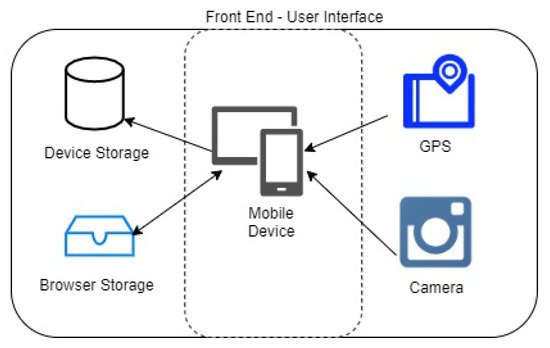

The top tier (Presentation layer/user interface), as presented in Figure 3, will be visible to the user. Through this level, the user browses, defines his options and receives the results of his personal preferences and choices. To support all clients, a web application with the principles of PWA (Progressive Web Applications) is employed, providing flexibility and giving the look and feel of a locally installed (native) application.

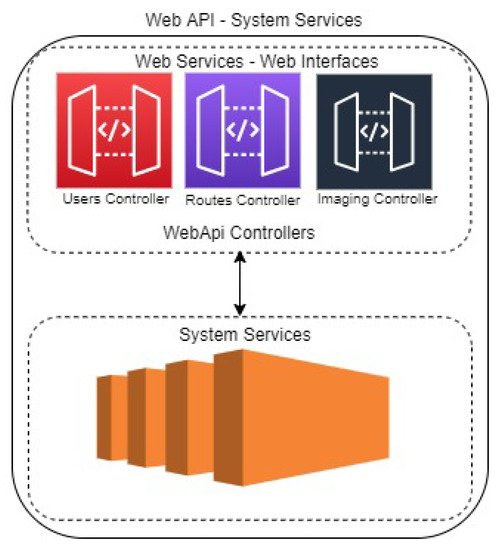

4.2. Web API—Middle Tier

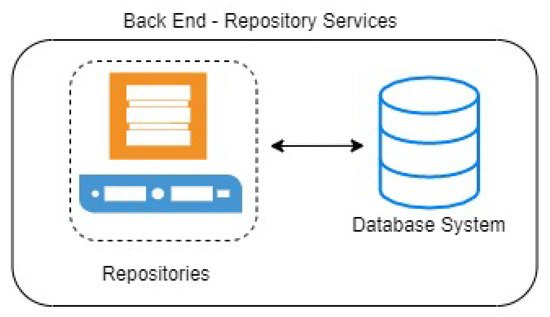

4.3. Repositories—Bottom Tier

References

- Institute of Greek Touristic Companies. Press Release 29 May 2019, Tourism Contribution in Greek Economy of 2018. Available online: https://insete.gr/wp-content/uploads/2020/02-/190529\char‘_PR-INSETE\char‘_Simvoli\char‘_Tourismou\char‘_2018.pdf (accessed on 21 October 2021).

- National Bank of Greece. Press Release 29 June 2020, National Bank of Greece’s Report for Monetary Policy of Years 2019–2020. Available online: https://www.bankofgreece.gr/enimerosi/-grafeio-typoy/anazhthsh-enhmerwsewn/enhmerwseis?announcement=cf55db30-b069-489d-9933-46af32f83a9a (accessed on 21 October 2021).

- da Silva Lopes, H.; Remoaldo, P.C.; Ribeiro, V.; Martín-Vide, J. Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Tourist Risk Perceptions—The Case Study of Porto. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6399.

- Viennas, E.; Ioannou, Z.-M.; Pavlidis, G.; Tzimas, G.; Sakkopoulos, E. HappyCruise: An architecture for Personalized Secure Boarding on Cruises. In Proceedings of the 2020 11th International Conference on Information, Intelligence, Systems and Applications IISA, Piraeus, Greece, 15–17 July 2020; pp. 1–8.

- Weiler, B.; Torl, M.; Moyle, B.D.; Hadinejad, A. Psychology in Tourism Doctoral Research. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2018, 43, 277–288.

- Williams, A. Tourism and hospitality marketing: Fantasy, feeling and fun. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2006, 18, 482–495.

- Knobloch, U.; Robertson, K.; Aitken, R. Experience, emotion, and eudaimonia: A consideration of tourist experiences and well-being. J. Travel Res. 2017, 56, 651–662.

- Oh, H.; Fiore, A.M.; Jeoung, M. Measuring experience economy concepts: Tourism applications. J. Travel Res. 2007, 46, 119–132.

- Mitas, O.; Bastiaansen, M. Novelty: A mechanism of tourists’ enjoyment. Ann. Tour. Res. 2018, 72, 98–108.

- Bello, D.C.; Etzel, M.J. The role of novelty in the pleasure travel experience. J. Travel Res. 1985, 24, 20–26.

- Förster, J.; Marguc, J.; Gillebaart, M. Novelty categorization theory. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2010, 4, 736–755.

- Ma, J. Emotions Derived from Theme Park Experiences: The Antecedents and Consequences of Customer Delight. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD, Australia, 2013.

- Izumi, R.; Kunieda, T.; Kometani, Y.; Gotoda, N.; Yaegashi, R. A Sightseeing Guidebook Automatic Generation Printing System According to the Attribute of Tourist (KadaTabi). In Joint Conference on Knowledge-Based Software Engineering; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 207–213.