Periodontitis is a multifactorial chronic inflammatory disease that affects tooth-supporting soft/hard tissues of the dentition. The dental plaque biofilm is considered as a primary etiological factor in susceptible patients; however, other factors contribute to progression, such as diabetes and smoking. Current management utilizes mechanical biofilm removal as the gold standard of treatment. Antibacterial agents might be indicated in certain conditions as an adjunct to this mechanical approach. Studies suggest efficacy in the use of adjunctive antimicrobials in patients with grade C periodontitis of young age or where the associated risk factors are inconsistent with the amount of bone loss present. Meanwhile, alternative approaches such as photodynamic therapy and probiotics showed limited supportive evidence, and more studies are warranted to validate their efficiency.

- antibacterial

- biofilms

- periodontal debridement

- bacterial resistance

- photodynamic therapy

- periodontal disease

- probiotics

- periodontitis

1. Introduction

Periodontitis is an inflammatory disease initiated by dysbiosis of the subgingival microbiome, with aberrant immune response, causing collateral damage to the tooth-supporting tissues and ultimately leading to tooth loss [1][2][15,16]. Dental plaque biofilm is considered as the primary etiologic factor for the majority of dental/periodontal diseases [3][17]. The gold standard of treatment for periodontitis is mechanical debridement of subgingival biofilm. Indeed, suppression of pathogenic microorganisms has for a long time been a keystone in regeneration and repair of periodontal tissues, which can be challenging using mechanical debridement alone, which must be complemented by patient-based plaque control programs [4][5][6][18,19,20]. For many decades, attempts have been made to improve the efficacy of mechanical treatment by introducing different adjuncts such as the use of antimicrobials/antibiotics at different dosages and routes of administration. However, the structural complexity of dental biofilm provides a shelter for many pathogenic microorganisms, making delivery to individual bacteria challenging [7][21]. In addition, due to the non-specificity of these drugs, they may target useful commensal species which counteract pathogenic biofilm development [8][22].

2. Structure of Biofilm

3. Management of Dental Biofilm

3.1. Periodontal Debridement: The Gold Standard for Periodontal Therapy

The objective of periodontal therapy is removal of the causative factor, i.e., dental biofilm from tooth surfaces. In the majority of cases, patients’ oral hygiene measures are adequate to resolve gingivitis. This may be accomplished by mechanical debridement to remove hard deposits from teeth which enhance retention of dental biofilm [13]. In periodontal pockets, subgingival debridement (SD) is pivotal for the removal of hard and soft sub-gingival deposits. To date, SD is the most effective method in the treatment of periodontitis [13]. It aims to remove the bulk of the dental biofilm, together with calculus which acts as a plaque-retentive factor and absorb bacterial toxins, thereby lowering the periodontal pathogens levels at subgingival sites, hence promoting recovery of periodontal health [13] by maintaining the level of periodontal pathogens to a threshold compatible with periodontal health [14]. This can be seen clinically through the reduction of inflammation and probing pockets depth (PPD), and the gain in clinical attachment levels (CAL) after SD using either hand or machine-driven instruments [15]. Therefore, periodontal debridement, with or without adjuncts, is still the gold standard modality for the treatment of periodontal diseases. However, long-term success is only ensured when the patients practice oral hygiene measures regularly [16].3.2. Adjunctive Systemic and Local Antimicrobials/Antibiotics in Periodontics

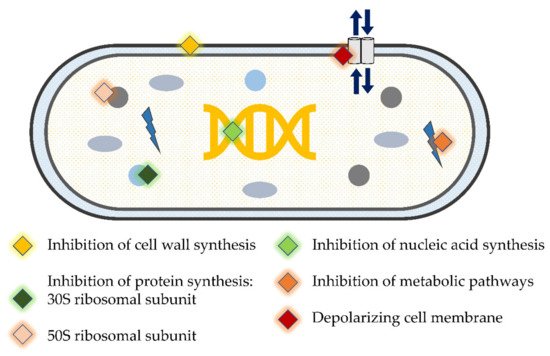

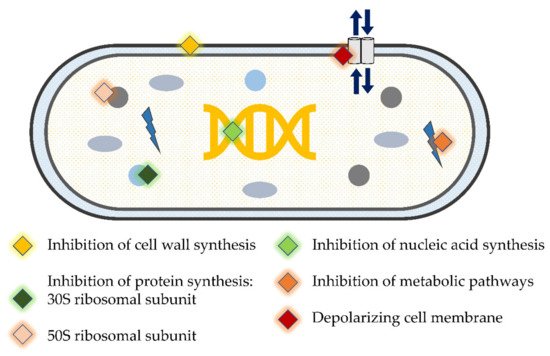

Although periodontitis is not related to specific bacteria, a number of periodontal pathogens have been identified. One of the goals of periodontal therapy is to move from a ‘pathogenic’ to a ‘healthy’ biofilm [17]. SD does not always produce the desired clinical improvement in all subjects or for the same subject in the long term [18][19]. This could be attributed to the operator’s lack of skill, the presence of inaccessible areas such as multi-rooted teeth, and/or the colonization by tissue invading species such as Porphyromonas gingivalis and Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans that cannot be completely eradicated by SD alone [20][21]. Thus, other forms of treatment modalities such as antibiotics/antimicrobials have been proposed as adjunctive therapy [22][23]. These therapeutic agents have diverse mechanisms of action (3.1. Periodontal Debridement: The Gold Standard for Periodontal Therapy

3.2. Adjunctive Systemic and Local Antimicrobials/Antibiotics in Periodontics

Although periodontitis is not related to specific bacteria, a number of periodontal pathogens have been identified. One of the goals of periodontal therapy is to move from a ‘pathogenic’ to a ‘healthy’ biofilm [33]. SD does not always produce the desired clinical improvement in all subjects or for the same subject in the long term [34,35]. This could be attributed to the operator’s lack of skill, the presence of inaccessible areas such as multi-rooted teeth, and/or the colonization by tissue invading species such as Porphyromonas gingivalis and Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans that cannot be completely eradicated by SD alone [36,37]. Thus, other forms of treatment modalities such as antibiotics/antimicrobials have been proposed as adjunctive therapy [38,39]. These therapeutic agents have diverse mechanisms of action (

4. Using Antimicrobials/Antibiotics as Adjunct to Periodontal Therapy

A number of studies using various antimicrobials against periodontal pathogens have been carried out. It is apparent that the antimicrobials can kill periodontal pathogens in in vitro biofilm models. However, some studies indicated that amoxicillin (AMX) + metronidazole (MET) were not efficient in reducing the bacterial count [30][31]. Nevertheless, most of the studies consistently reported that the combination of these two antibiotics was superior to using either of them alone, particularly against red complex bacteria [32][33][34][35]. Similar results with regard to these bacteria were obtained with other antibiotics including azithromycin (AZM) [32][35], minocycline [36], and active organic ingredients of mouthrinses [37][38][39]. However, it is important to acknowledge that owing to greater tolerance to antimicrobials, the minimum inhibitory concentration calculated in in vitro studies would purportedly be lower and would bear little relevance to in vivo situations [18][40]. Furthermore, the majority of these studies used laboratory strains in their biofilm models, which apparently differ from clinical strains in their behavior and resistance to antimicrobials [41].

Many studies have been conducted to evaluate the additional benefits of using antibiotics within the course of periodontal therapy. Results from some of these studies have concluded that antibiotics are important adjuncts to SD in specific situations [42][43][44]. The additional clinical benefits of antibiotics are more pronounced in molar sites than in non-molar sites [45]. Following SD, the administration of broad-spectrum antibiotics for three to seven days improves microbiological outcomes compared to SD alone [44]. In regenerative periodontal therapy, better clinical outcomes could be achieved when systemic antibiotics are prescribed for patients [46]. On the other hand, many studies have reported that the use of antibiotics as an adjunct to periodontal therapy has no additional clinical benefits. Following periodontal surgery, the adjunctive use of AMX alone [47] or in combination with MET [48] for more than one week postoperatively provides no additional clinical improvements after one year. Similarly, the use of AZM as an adjunct to SD for the treatment of periodontitis seems to have no role in improving clinical outcomes compared to SD alone [49] despite the reduction in the levels of periodontal pathogens in deep periodontal pockets [50]. Precaution in prescribing antibiotics for patients with periodontal disease is advised and should be limited to certain conditions. To date, available evidence suggest prescribing adjunctive antimicrobials in patients with grade C periodontitis of young age or where the associated risk factors are inconsistent with the amount of bone loss present.A number of studies using various antimicrobials against periodontal pathogens have been carried out. It is apparent that the antimicrobials can kill periodontal pathogens in in vitro biofilm models. However, some studies indicated that amoxicillin (AMX) + metronidazole (MET) were not efficient in reducing the bacterial count [66,67]. Nevertheless, most of the studies consistently reported that the combination of these two antibiotics was superior to using either of them alone, particularly against red complex bacteria [68,69,70,71]. Similar results with regard to these bacteria were obtained with other antibiotics including azithromycin (AZM) [68,71], minocycline [72], and active organic ingredients of mouthrinses [73,74,75]. However, it is important to acknowledge that owing to greater tolerance to antimicrobials, the minimum inhibitory concentration calculated in in vitro studies would purportedly be lower and would bear little relevance to in vivo situations [34,76]. Furthermore, the majority of these studies used laboratory strains in their biofilm models, which apparently differ from clinical strains in their behavior and resistance to antimicrobials [77].

5. Novel Antibacterial Agents and Strategies to Overcome Bacterial Resistance in Dental Biofilm: Pros and Cons

Interest in seeking novel alternative adjuncts to SD was raised due to limitations of conventional SD methods [51][52] and drawbacks of antimicrobials/antibiotics. Antimicrobial photodynamic therapy (aPDT) and laser are among the suggested methods that have been thoroughly investigated. Additionally, probiotics emerged as another promising approach to prevent and treat periodontal disease [53][54]. The use of lasers to debride periodontal pockets and ablate subgingival deposits has gained some traction in dental practice [55]. The utilization of a low-level laser light in combination with a photosensitizer, e.g., toluidine blue, is known as aPDT. The principle of this technique is based on light exposure of a photosensitizer releasing highly reactive oxygen radicals which destroy bacteria in periodontal pockets [56]. Additionally, photonic energy is presumed to enhance tissue healing by bio-stimulatory effects; further improvement of clinical parameters is therefore expected, such as the reduction of PPD and bleeding on probing, as well as CAL gain [57]. Concomitant improvement in clinical and microbiological parameters when aPDT was used as adjunct to SD was reported in several studies [58][59][60][61]. This was consistent with the results from a current systematic review and meta-analysis that have shown positive effects on the clinical outcomes of using aPDT together with laser, with a high impact on key periodontal pathogens, particularly the red complex [62]. However, other trials showed only a reduction of periodontal pathogens without significant difference in clinical parameters when compared to SD only [63][64]. In addition, results from other studies indicated that neither microbiological nor clinical parameters were improved following the application of laser or aPDT [65][66][67][68][69][70][71] (| Author, Year | Study Design, Follow-Up | Study Population | Clinical/Microbiological Parameters | aPDT Treatment Modalities | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author, Year | Study Design, Follow-Up | Study Population | Strain of Probiotic | Mode/Frequency of Administration | Clinical/Microbiological Parameters | ||||||||||||||

| Improvement in microbiological and clinical parameters | § | ||||||||||||||||||

| Moreira et al., 2015 [61] | Moreira et al., 2015 [118] | Split-mouth RCT, 3-months | Patients with generalized AgP (n = 20) |

| |||||||||||||||

| Improvement in microbiological and clinical parameters | § | ||||||||||||||||||

| Invernici et al., 2018 [72] | Invernici et al., 2018 [134] | Parallel arm RCT, 3-months | Chronic periodontitis patients (n = 41) |

|

| SD + Diode laser (670 nm)/phenothiazine chloride (10 mg/mL) photosensitizer | |||||||||||||

| Bl | (HN019) 1 × 10 | 9 | CFU | Lozenges (10 mg) 2×/day for 30-days |

|

|

| Gandhi et al., 2019 [59] | Gandhi et al., 2019 [116] | ||||||||||

| Invernici et al., 2020 [73] | Invernici et al., 2020 [133]Split-mouth, RCT, 9-months | Periodontitis patients (n = 26) | Parallel arm RCT, 3-months | Chronic periodontitis patients (n = 30) |

|

|

SD + Diode laser (810 nm)/ICG photosensitizer | ||||||||||||

| Bl | (HN019) 1 × 10 | 9 | CFU | Lozenges 2×/day in the morning and before bedtime for 30-days |

|

| Annaji et al., 2016 [60] | Annaji et al., 2016 [117] | Split-mouth RCT, 3-months | Patients with AgP (n = 15) |

|

|

|

SD+ Diode Laser (810 nm) | |||||

| Wadhwa et al., 2021 [58] | Wadhwa et al., 2021 [115] | Split-mouth RCT, 6-months | Chronic periodontitis patients (n = 30) | Total viable anaerobic count | SD + Diode laser (810 nm)/ICG photosensitizer | ||||||||||||||

| Improvement in microbiological parameters only | § | ||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

| Improvement in clinical parameters only | § | ||||||||||||||||||

| Laleman et al., 2020 [74] | Laleman et al., 2020 [135] | Parallel arm RCT, 6-months | Chronic periodontitis patients (n = 39) | Lr (DSM 17,938 and ATCC PTA 5289) 2 × 108 CFU each | Five probiotic drops applied to residual pocket immediately after SD. Then each patient instructed to use lozenges 2×/day after brushing for 3-months |

|

|

|

|||||||||||

| Tekce et al., 2015 [75] | Tekce et al., 2015 [137] | Parallel arm RCT, 12-months | Chronic periodontitis patients (n = 30) | Lr (DSM 17,938 and ATCC PTA 5289) 2 × 108 CFU each | Lozenges 2×/day after brushing for 3-weeks | Muzaheed et al., 2020 [63] | Muzaheed et al., 2020 [120] | Parallel arm RCT, 3-months | Periodontitis patients (n = 45) |

|

|

|

SD + Diode laser (660 nm)/methylene-blue (0.005%) photosensitizer | ||||||

| Chondros et al., 2009 [64] | Chondros et al., 2009 [121] | Parallel arm RCT, 6-months | Periodontitis patients (n = 24) |

|

|

|

SD + Diode Laser (670 nm)/phenothiazine chloride (10 mg/mL) photosensitizer | ||||||||||||

| No improvement in microbiological and clinical parameters | § | ||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Improvement in microbiological parameters only | § | ||||||||||||||||||

| Dhaliwal et al., 2017 [76] | Dhaliwal et al., 2017 [136] | Parallel arm RCT, 3-months | Chronic periodontitis patients (n = 30) | Sf (T-110 JPC), 30 × 107 CFU, Cb (TO-A HIS), 2 × 106 CFU, Bm (TO-A JPC), 1 × 106 CFU and Ls (HIS), 5 × 107 CFU | Bifilac lozenges 2×/day or 21-days |

|

|

|

|||||||||||

| Teughels et al., 2013 [77] | Teughels et al., 2013 [138] | Parallel arm RCT, 3-months | Chronic periodontitis patients (n = 30) | Lr (DSM17938 and ATCC PTA5289) 9 × 108 CFU each | Lozenges 2×/day for 3-months |

|

|

|

Chitsazi et al., 2014 [70] | Chitsazi et al., 2014 [127] | Split-mouth RCT, 3-months | Patients with AgP (n = 24) |

|

|

|

||||

| No improvement in microbiological and clinical parameters | SD + Diode Laser (670–690 nm) | ||||||||||||||||||

| § | Rühling et al., 2010 [71] | Rühling et al., 2010 [128] | Parallel arm RCT, 3-months | Periodontitis patients (n = 54) |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Pudgar et al., 2021 [78] | Pudgar et al., 2021 [139] |

|

Parallel arm RCT, 3-months | SD + Diode Laser (635 nm)/5% tolonium chloride photosensitizer | |||||||||||||||

| Chronic periodontitis patients (n = 40) | Lb | (CECT7480) and | Lp (CECT7481), 6.0 × 109 CFU/mL each | One lozenge/day |

|

|

|

Queiroz et al., 2015 [68] Queiroz et al., 2014 [69] | Queiroz et al., 2015 [125] Queiroz et al., 2014 [ | ||||||||||

| Morales et al., 2018 [79 | 126] | ] | Morales et al., 2018 [Parallel arm RCT, 3-months | 140Periodontitis smoker patients (n = 20) | ] |

|

Parallel arm RCT, 9-months |

| Chronic periodontitis patients (n = 47) |

| SD + Diode Laser (660 nm)/phenothiazine chloride (10 mg/mL) photosensitizer | ||||||||

| Lrh | (SP1) 2 × 10 | 7 | CFU | One sachet in water (150 mL) and ingest it once a day after brushing for 3-months |

|

|

|

Tabenski et al., 2017 [66] | Tabenski et al., 2017 [123] | Parallel arm RCT, 12-months | Periodontitis patients (n = 45) |

|

|

|

SD + Diode Laser (670 nm)/phenothiazine chloride photosensitizer | ||||

| Hill et al., 2019 [65] | Hill et al., 2019 [122] | Split-mouth RCT, 6-months | Periodontitis patients (n = 20) |

|

|

|

SD + Diode laser (808 nm)/ICG photosensitizer | ||||||||||||

| Pulikkotil et al., 2016 [67] | Pulikkotil et al., 2016 [124] | Split-mouth RCT, 3-months | Periodontitis patients (n = 20) |

|

|

|

SD + LED lamp (red spectrum, 628 Hz)/methylene blue photosensitizer | ||||||||||||