Despite an intensive research effort in the past few decades, prostate cancer (PC) remains a top cause of cancer death in men, particularly in the developed world. The major cause of fatality is the progression of local prostate cancer to metastasis disease. Treatment of patients with metastatic prostate cancer (mPC) is generally ineffective. Based on the discovery of mPC relying on androgen for growth, many patients with mPC show an initial response to the standard of care: androgen deprivation therapy (ADT). However, lethal castration resistant prostate cancers (CRPCs) commonly develop. It is widely accepted that intervention of metastatic progression of PC is a critical point of intervention to reduce PC death. Accumulative evidence reveals a role of RKIP in suppression of PC progression towards mPC.

1. Introduction

In the developed world, prostate cancer (PC) is the most frequently diagnosed male malignancy and a major cause of cancer death in men

[1]. The disease is initiated from prostate epithelial cells as high-grade prostatic intra-epithelial neoplasia (HGPIN) lesions that evolve to invasive prostate adenocarcinoma or PC which can progress to metastasis

[2]. PCs are graded based on Gleason scores (GS) or GS-based World Health Organization (WHO) grading system which categorizes PC into WHO grade group 1–5

[3][4][5][3,4,5].

Prostate cancers are characterized with a high degree of disparity in terms of its prognosis. While tumors with GS ≤ 6 or WHO grade group 1 are generally indolent, others possess high-risk of progression. Local PCs are managed with watchful waiting (active surveillance) and curative therapies: radical prostatectomy (RP) or radiation therapy (RT)

[6][7][8][9][6,7,8,9]. Approximately 30% of patients will experience disease relapse or biochemical recurrence (BCR) based on increases in serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA)

[10]. BCR is defined with elevations of serum PSA > 0.2 ng/mL after RP or > 2 ng/mL above the nadir following RT

[11]. Relapsed tumors elevated risks of metastasis; 24–34% of patients following BCR will develop metastatic PC (mPC)

[12][13][12,13].

Built on the androgen-dependence nature of PC discovered in 1940s, current standard of care for mPCs remains androgen deprivation therapy (ADT)

[14][15][14,15]. Despite remarkable initial response in more than 80% of patients with mPC, ADT is essentially a palliative care as metastatic castration-resistant PCs (mCRPCs) commonly develop

[16][17][16,17]. Owing to extensive research efforts, multiple options are available to manage CRPCs, including taxane-based chemotherapy, anti-androgens targeted therapy involving either abiraterone or enzalutamide

[17][18][19][17,18,19], and immunotherapy

[20][21][20,21]. However, these therapies only offer modest survival benefits

[17][22][17,22]. From this perspective, interventions targeting early-stage progressions of BCR and metastasis are more desirable than treating CRPC or mCRPC.

Metastasis contributes to more than 90% of cancer deaths

[23][24][23,24], and is regulated by complex networks. Epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) is critical in promoting metastasis; EMT increases cancer cell’s migratory and invasion capacities, which are essential properties in facilitating the establishment of cancer cells at the secondary organs from primary site

[25][26][25,26]. EMT is a major contributor to cancer stem cells

[27], including prostate cancer stem cells (PCSCs)

[28]. PCSCs are a major source of PC metastasis

[28]. Other processes contributing to PC metastasis include cell proliferation regulated by Raf-MEK-ERK and PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathways

[29][30][29,30], the EZH2 polycomb protein

[31][32][33][31,32,33], and NFκB

[34][35][34,35]. Intriguingly, all these processes are connected to a suppressor of PC metastasis, Raf kinase inhibitor protein (RKIP) (

Figure 1)

[36][37][36,37].

2. RKIP as a Tumor Suppression of Prostate Cancer (PC)

Consistent with RIKP’s potential role in molecular events relevant to tumor suppression, RKIP downregulations, and RKIP’s associations with cancer progression, RKIP-derived tumor suppressive activities have been reported in multiple cancer types, including urogenital cancers (bladder cancer

[38][84], clear cell renal cell carcinoma

[39][40][41][85,86,87], and PC

[42][43][88,89]), breast cancer

[44][90], pancreatic cancer

[45][91], hepatoma

[46][92], non-small cell lung cancer

[47][93], gastric cancer

[48][94], and others

[49][95].

2.1. RKIP-Mediated Suppression of PC Tumorigenesis and Metastasis

2.1.1. Facilitation of PC Initiation and Metastasis via Downregulation of RKIP at the Protein Level

The first evidence for RKIP as a metastatic suppressor of PC started with the identification of RKIP downregulation in LNCaP cells-derived metastatic C4-2B cells compared to their parental cells

[50][96]; functionally, downregulation of RKIP elevated metastatic potential of C4-2B cells

[42][88]. Specifically, restoration of RKIP expression in C4-2B cells to a comparable level in LNCaP cells reduced C4-2B cells’ invasion ability in vitro and the cells’ ability to produce lung metastasis in an orthotopic PC model without affecting its ability in forming primary tumors

[42][88]. Downregulation of RKIP at the protein level was observed following PC progression from low grade (low Gleason score) to high grade and the downregulation was particularly evident in metastatic PCs (

n = 22)

[42][88]. In comparison to LNCaP cells, C4-2B cells displayed an increase in ERK activation, and inhibition of ERK activation with PD098059 decreased C4-2B cell invasion capacity in vitro.

Further analysis of RKIP expression in a tissue microarray containing non-tumor prostate tissues (

n = 57), primary PCs (

n = 79), and metastatic CRPC (

n = 55), RKIP downregulation was detected in 48% of primary (or local) PCs and 89% of mCRPCs respectively

[43][89]. RKIP downregulation in primary PCs stratifies the risk of PC recurrence (biochemical recurrence) following surgery and remains an independent risk factor of relapse after adjusting for Gleason score, maximal tumor diameter, pathological stage, surgical margin status, digital rectal examination, PSA, and gland weight

[43][89].

The RKIP downregulations in primary PC compared to non-cancerous prostate tissues and its further downregulation in mPC vs. primary PC also occurred following PC progression in TRAMP mice

[51][97]. While systemic knockout of RKIP had minimal impact on mouse health

[52][98], RKIP deficiency significantly enhanced PC formation and metastasis in TRAMP mice

[51][97]. Collectively, clinical and transgenic mouse (functional) studies support RKIP’s action in suppressing PC tumorigenesis and metastasis. However, whether decreases in PC metastasis in

RKIP−/−;TRMAP mice were a direct result of reductions in primary PC formation requires additional investigations. Major limitations of the above studies include lack of analyses of RKIP expression at the mRNA level and utilization of more targeted transgenic model such as prostate-specific

RKIP−/− mice.

2.1.2. No Apparent Reduction of RKIP mRNA Expression Following PC Pathogenesis

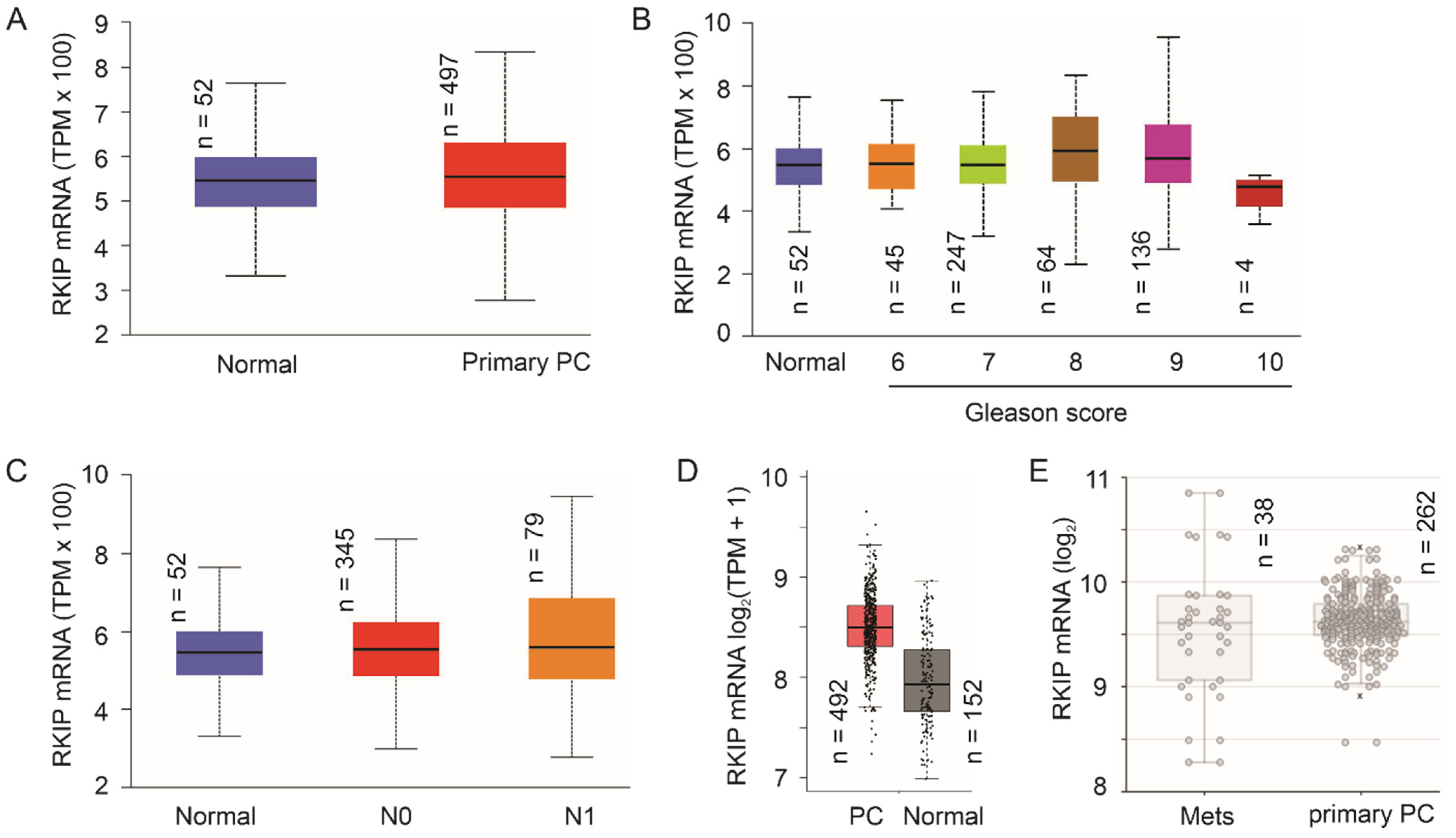

The number of publications related to RKIP reductions following PC evolution remains limited. This might be in part attributed to the highly heterogenous nature of PC and challenges in studying RKIP downregulation at the protein level. With advances in DNA sequencing (Next-generation sequencing), an ever-increasing number of cancer genetics and gene expression data have been accumulated and made available. Using TCGA RNA-seq data on prostate tissue (

n = 52) and PC samples (

n = 497) available from the UALCAN platform (

ualcan.path.uab.edu/home, accessed on 6 October 2021)

[53][99], we did not find apparent downregulation of RKIP in PC, high grade PCs, and lymph node metastasis (

Figure 14A–C). Similar observations could be obtained using the GEPIA2 platform

[54][100] with more prostate tissues (

n = 152) (

Figure 14D). Furthermore, using the Sawyers microarray dataset

[55][101] within the R2: Genomics Analysis and Visualization platform (

http://r2.amc.nl, accessed on 3 December 2021), RKIP mRNA was not significantly expressed at reduced levels in mPCs compared to primary PCs

(Figure 2E). This strongly suggests the RKIP downregulation observed in PC occurs at least in part at post-mRNA levels. Future research should explore these mechanisms.

3. Conclusions

The research activities in the past 20 years collectively demonstrated RKIP as a tumor suppressor of PC tumorigenesis and metastasis. This knowledge is supported by (1) functional evidence derived from in vitro, in vivo (xenograft and transgenic mouse models), and clinical studies as well as (2) mechanistic pathways contributing to RKIP-derived suppression of PC. Future research should explore the functionality and underlying mechanisms for RKIP mediated suppression of PC using more refined transgenic models, including mice with prostate-specific expression of RKIP and its mutants. The latter may help to define the regulations relevant to RKIP tumor suppressive actions; this is important, as RKIP can be switched to promote tumorigenesis following its phosphorylation at S153

(Figure 2). Additionally, mechanisms leading to RKIP downregulation in PC and RKIP’s involvement in other aspects of PC progression should also be investigated (see

Section 5 for details).