Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), the most common malignancy of the pancreas, accounts for 3% of all cancers and 7% of cancer-related deaths and is expected to claim 48,220 lives in 2021 in the US (American Cancer Society). Despite continued scientific efforts, the 5-year survival rate of all surveillance, epidemiology, and end results (SEER) stages combined remains a dismal 10% (American Cancer Society). Surgery remains the only curative option for PDAC patients.

CXCL12, a member of the CXC family of chemokines, is secreted by the activated fibroblasts (for which we use the terms aPSCs and CAFs interchangeably in this review) of the TME and is a crucial mediator reported to contribute to growth and metastasis in PDAC and several other solid tumors, including head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) and breast, ovarian, and colorectal carcinomas. CXCL12 has a pervasive influence in PDAC by increasing proliferation, enhancing invasion and metastasis, and promoting chemoresistance and immune evasion of tumor cells.

1. Introduction

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), the most common malignancy of the pancreas, accounts for 3% of all cancers and 7% of cancer-related deaths and is expected to claim 48,220 lives in 2021 in the US (American Cancer Society). Despite continued scientific efforts, the 5-year survival rate of all surveillance, epidemiology, and end results (SEER) stages combined remains a dismal 10% (American Cancer Society). Surgery remains the only curative option for PDAC patients. However, over 70% of patients do not qualify for surgical intervention due to locally advanced tumors or their metastatic spread at the time of diagnosis, contributing to the high mortality associated with PDAC

[1]. Chemotherapy in the forms of FOLFIRINOX (a cocktail of 5-fluorouracil, irinotecan, and oxaliplatin) and a combination of gemcitabine with nab-paclitaxel (nanoparticle albumin-bound paclitaxel) remain the mainstay of metastatic PDAC treatment

[2]. Even with these therapies, the 5-year survival rates for patients with regionally advanced and metastatic disease stand at 12% and 3%, respectively.

A major obstacle to effectively treating PDAC is attributable to its unique tumor microenvironment (TME). Unlike many other solid cancers, an overwhelmingly large proportion—sometimes as much as 80%—of the total tumor volume in PDAC is comprised of nontumor stroma

[3]. This dense, fibrous stroma, referred to as desmoplasia, contains extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins as well as stromal cells (including immune cells such as regulatory T cells (Tregs), myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), and tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs)), fibroblasts (such as pancreatic stellate cells (PSCs) and cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs)), and endothelial cells. The ECM is composed of collagens, laminin, fibronectin, glycosaminoglycans, and other soluble factors

[4]. Together, the cellular and structural components of the TME function as a dynamic network that drives tumor cell growth, invasion, metastasis, and therapeutic resistance.

In normal pancreatic tissue, the structural components of the ECM function as a scaffold and signaling matrix to maintain tissue homeostasis, while resident fibroblasts and quiescent PSCs conserve connective tissue organization and immune cells engage in immune surveillance. However, upon tumor initiation, cancer cells manipulate the surrounding microenvironment to their own benefit by shifting these components into a state that allow tumorigenesis. Cancer cells can alter the TME directly (via the secretion of signaling molecules) as well as indirectly (through the resulting hypoxia and oxidative stress), the effects of which include fibroblast/PSC activation and recruitment, blood vessel formation, and the initiation of an inflammatory response

[5]. Upon their activation, PSCs show increased proliferation and migration and assume a myofibroblast-like phenotype that involves the expression of alpha-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), fibroblast-specific protein-1 (FSP-1), and fibroblast activation protein-alpha (FAP-α)

[6]. Activated PSCs (aPSCs) also show excessive deposition of ECM proteins, resulting in increased interstitial pressure and tissue rigidity, which can contribute to impaired drug delivery and increased cancer cell migration

[7][8][7,8]. Furthermore, aPSCs secrete chemokines, growth factors, and other soluble proteins that can enhance tumor cell growth and migration, promote angiogenesis, and induce immune evasion.

CXCL12, a member of the CXC family of chemokines, is secreted by the activated fibroblasts (for which we use the terms aPSCs and CAFs interchangeably in this review) of the TME and is a crucial mediator reported to contribute to growth and metastasis in PDAC and several other solid tumors, including head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) and breast, ovarian, and colorectal carcinomas

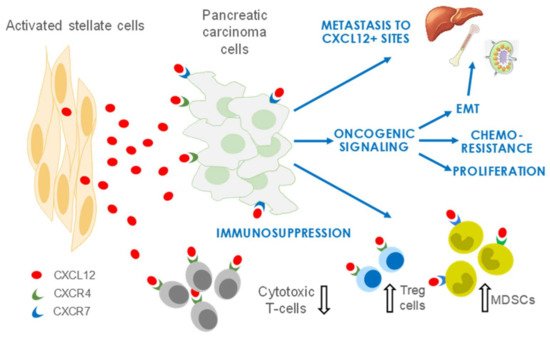

[9][10][11][9,10,11]. CXCL12 has a pervasive influence in PDAC by increasing proliferation, enhancing invasion and metastasis, and promoting chemoresistance and immune evasion of tumor cells (

Figure 1). The two receptors of CXCL12, CXC receptor 4 (CXCR4) and atypical chemokine receptor 3 (AKRC3, also known as CXCR7), are expressed on PDAC cells, and an elevated expression of CXCR4 is associated with a poor prognosis in several cancer types

[12]. In this hypothesis paper, we discuss the oncogenic functions of CXCL12 and its potential as a therapeutic target in PDAC.

Figure 1. Roles of stroma/stellate cells in PDAC. CXCL12 secreted predominantly by activated stellate cells/CAFs promotes an environment conducive to PDAC growth and metastasis. CXCL12 also has crucial functions in immune evasion and development of resistance to chemotherapies. EMT, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition; Treg, regulatory T cell; MDSCs, myeloid-derived suppressor cells.

2. CXCL12 Signaling in PDAC

2.1. CXCL12 Promotes PDAC Survival and Proliferation Signaling

CXCL12 promotes cell survival and expansion via the stimulation of dominant oncogenic RAS-MAPK and PI3K-AKT signaling pathways. Given that aPSCs form the bulk of the PDAC stroma, most studies have evaluated the effect of PSCs on PDAC cells to understand the PDAC stromal–tumor interactions. Early understanding of interactions between PSCs and PDAC cells comes from two-dimensional tumor cell line studies that showed the effect of PSC-conditioned media on tumor cell growth and survival. In one such study

[13][39], Marchesi et al. noted that PSCs increased the proliferation, invasion, and transendothelial migration of CXCR4

+ pancreatic cancer cell lines and protected the tumor cells from apoptosis in vitro. Further, PSCs also enhanced the growth rate of several PDAC models in vivo in the subcutaneous site

[14][40]. Importantly, Hwang et al.

[15][41] further substantiated these findings by demonstrating that PSCs reduced latency periods and enhanced tumor growth and metastasis in an orthotopic model of PDAC. The co-implantation of a human pancreatic tumor cell line with human PSCs in mouse pancreas resulted in increased take rates and higher tumor burdens compared with tumor cells alone. PSCs also enhanced the rate of metastasis to the lymphatic, hepatic, and peritoneal sites

[15][41]. Importantly, several other reports have corroborated the supportive contribution of CXCL12 to PDAC growth and migration in vitro

[16][17][18][42,43,44], reinforcing the concept that CXCL12 production by PSCs might underlie their facilitation of PDAC growth and progression. Biochemical analyses further demonstrate that CXCL12 supports KRAS-induced MAPK and AKT signaling to promote tumor cell survival and proliferation

[19][17][20][21][22][36,43,45,46,47]. Interestingly, an ERK inhibitor suppressed cell–cell interactions in an in vitro co-culture model of PDAC with PSCs, suggesting that ERK signaling is important in tumor and stellate cells

[23][48]. Most of these studies implicate CXCR4 as the primary mediator in CXCL12-induced activation of the MAPK and AKT pathways. While the function of CXCR7 is less well-characterized, CXCR7 has been shown to contribute to increased MAPK signaling in receptor positive PDAC cell lines

[19][36]. Similar to PDAC, CXCL12 also amplifies MAPK signaling in breast, colon, head and neck, and esophageal cancers

[24][25][26][27][49,50,51,52].

2.2. CXCL12 Signaling Promotes Immune Evasion

PDAC so far has remained disappointingly refractory to immunotherapy targeting immunological checkpoints such as cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4) and programmed cell death protein-1 and its ligand (PD-1/PD-L1). Those same immuno-oncology drugs are now approved for several other solid tumors, including cancers of the head and neck, bladder, and kidney

[28][53]. Thus, there is great interest in understanding the biological mechanisms underlying PDAC resistance to immunotherapy

[29][54].

The dense stroma of PDAC has a complex, pleotropic immunomodulatory function in PDAC progression, and understanding the stromal-immune cell interaction is crucial in designing immune therapies for this disease. Most of the understanding of the PDAC immune microenvironment is based on findings from genetically engineered mouse models (GEMMs) that indicate that PDAC is a “cold” or “non-inflamed” tumor characterized by the absence of antigen-specific T-cell responses and elevated levels of immunosuppressive MDSCs and Tregs

[30][31][32][55,56,57]. While such a T-cell exclusion has been described in human PDAC, multiple studies reported that a fraction (16–35%) of patients exhibited CD4

+ and CD8

+ T-cell infiltration and that higher numbers of T cells in juxtatumoral stroma correlated with better survival

[33][34][35][36][37][38][58,59,60,61,62,63]. The “immune ignorance” model views PDAC as a cold tumor, thus favoring priming the initial T-cell response as an immunotherapy strategy

[39][64]. Conversely, the “immune suppressive” model of PDAC advocates for the utility of enhancing T-cell activation with checkpoint inhibitors such as monoclonal antibodies to CTLA-4 or PD-1/PD-L1. Evidence supporting each model exists, and the best strategy perhaps depends on the immune landscape of the individual tumor. Regardless, activated stromal fibroblasts are crucial immune modulatory cells. For example, the depletion of CXCL12-producing fibroblast activation protein-α (FAP

+) CAFs allowed for immunological control of tumor growth in

KPC (

Pdx1Cre, KrasLSL-G12D, and

Trp53LSL-R172H) mice and a combination of CAF depletion or CXCR4 inhibition with AMD3100 with anti–PD-L1 resulted in tumor regressions

[40][41][65,66]. This synergistic response was recapitulated in viable resected human PDAC slices by Seo and coworkers, who elegantly demonstrated improved homing of CD8

+ T cells to juxtatumoral stromal regions and enhanced CD8

+ T cell-mediated antitumor activity by combined blockade of CXCR4 and PD-1

[33][58]. Furthermore, a recent study showed that PDAC excludes T cells and resists inhibitors of PD-1 checkpoints when cancer cells are coated with covalent heterodimers of CXCL12 and keratin 19 (KRT19) formed by transglutaminase-2 (TGM2). Interrupting the expression of KRT19 or TGM2 in mouse PDAC allowed the infiltration of T cells and sensitized the response to anti–PD-1 agents

[42][67].

2.3. CXCL12 Signaling Promotes Angiogenesis

Angiogenesis is the process of new blood vessel development from pre-existing vessels. Tumors hijack this cellular process for their sustenance. Fibroblast-derived CXCL12 in concert with pancreatic tumor-derived CXCL8 has been shown to promote proliferation, invasion, and tube formation of endothelial cells in vitro

[43][68]. Furthermore, in a subcutaneous mouse model of PDAC, CXCR4 blockade by AMD3100 reduced intratumor blood flow and tumor vascular density, supporting that CXCL12 can promote angiogenesis

[44][69]. Together, these studies suggest that CXCL12 supports angiogenesis in PDAC.

2.4. CXCL12 Signaling Promotes Chemoresistance

The nucleoside analog gemcitabine remains a cornerstone of PDAC therapy, but inherent or acquired resistance to gemcitabine limits its benefit to patients. As a result, considerable effort has been expended to decipher the underlying mechanisms of resistance to gemcitabine. Stroma-tumor interactions in general and CXCL12-CXCR4 signaling in particular contribute significantly to drug resistance in PDAC. The CXCL12/CXCR4 axis promotes innate gemcitabine resistance by activating pro-survival pathways and contributes to acquired resistance via the upregulation of CXCR4 expression. CXCL12 protects PDAC cells from the cytotoxic effects of gemcitabine in part by NF-kB-dependent anti-apoptotic signaling, promoting the expression of survival proteins such as Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, and survivin

[45][70]. CXCL12 also induces an autocrine IL-6 secretion loop in PDAC cells to further enhance chemoresistance

[46][71]. Gemcitabine also counterproductively increases CXCR4 and CXCR7 expression in PDAC cells, which in turn enhances CXCL12 production by stromal cells and renders PDAC cells more invasive and resistant to gemcitabine

[47][48][72,73]. Consistent with a chemoprotective role of CXCL12 signaling, its disruption by AMD3100 has sensitized PDAC to gemcitabine in vitro and in vivo

[49][74]. AMD3100 is also known to sensitize prostate cancer cells to docetaxel and colon cancer cells to 5-fluorouracil

[50][51][52][75,76,77], implying that the blockade of CXCL12 signaling could have wider application as a chemosensitization strategy.