1. Lipid Droplet Biogenesis. General Aspects

Mammalian cells accumulate excess neutral lipids, i.e., triacylglycerol (TG) and cholesterol esters (CE), in cytoplasmic organelles known as lipid droplets (LD). While LDs are present in almost all known cell types, their number, size and composition vary greatly from cell to cell and even within a given cell type. LDs are spherical particles composed of a phospholipid monolayer which encases a core made up mainly of TG and CE

[1][2][3][1,2,3]. A large number of unique phospholipid molecular species has been identified in the LD monolayer. Most of these belong to the choline- and ethanolamine-containing glycerophospholipid classes (abbreviated as PC and PE, respectively), which represent approx. 64% and 24% of the total. Minor amounts of other classes such as phosphatidylinositol (PI), phosphatidylserine (PS), phosphatidic acid (PA), sphingomyelin, and lysophospholipids have also been identified

[1][2][3][1,2,3].

The phospholipid monolayer is decorated with a variety of proteins that play numerous roles, ranging from regulating lipid mobilization from and to the organelle, to serving to support and stabilize the organelle structure itself. Of particular importance is the PAT family of proteins, which includes perilipin-1 (PLIN1), adipophilin (ADPR, PLIN2) and TIP47 (Tail-Interacting protein of 47 Kda, PLIN3)

[4]. PLIN1 contributes to the growth and stabilization of LDs

[5]. PLIN2 is involved in adipocyte differentiation and appears to be important for proper hydrolysis of the LDs

[6]. The functions of PLIN3 are related to the regulation of lipolysis in skeletal muscle cells

[7]. PLIN4 has been implicated in stabilizing the LD by interacting directly with TG moieties when their phospholipid coverage is limited

[8]. PLIN5 appears to be involved in protective roles against mitochondrial damage and endoplasmic reticulum stress in liver

[9].

In addition to the PAT proteins, numerous enzymes related to lipid metabolism have also been found on the surface of LDs; these include adipose triacylglycerol lipase (ATGL)

[10], hormone-sensitive lipase

[11], cytidine triphosphate:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase

[12][13][12,13], lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferases

[14], long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase 3

[15], lipin-1

[16][17][16,17], cyclooxygenase

[18], and group IVA cytosolic phospholipase A

2 (cPLA

2α)

[19][20][19,20], among others. Some of these proteins also participate in signaling

[1][21][22][23][24][1,21,22,23,24]. Thus, the presence of such a varied number of lipid-metabolizing enzymes attests to the role of LDs as intracellular hubs where lipid signaling enzymes dock and interact to activate select pathways

[1][21][22][23][24][1,21,22,23,24].

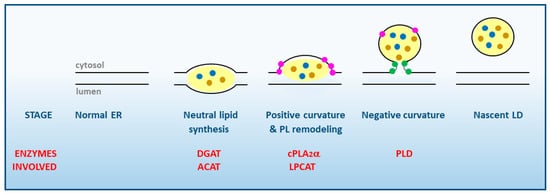

Although significant progress has been made in recent years, the mechanism of LD biogenesis is yet to be fully established. Formation of LDs involves a large number of steps and is carried out in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), where the amphipathic monolayer of LDs originates

[25][26][25,26] (

Figure 1).

Figure 1. Stages of LD synthesis at the cytosolic face of smooth ER membranes. The various enzymes of lipid metabolism participating in each stage are highlighted in red. Note the essential role of cPLA2α in favoring the induction of positive membrane curvature. TG and CE inside the LD are represented by brown and blue dots, respectively. Lysophospholipids at the membrane are highlighted as pink dots, phosphatidic acid as green dots. PL, phospholipid; DGAT, diacylglycerol:acyl-CoA acyl transferase; ACAT, acyl-CoA:cholesterol acyl transferase; PLD, phospholipase D; LPCAT, lysophosphatidylcholine:acyl-CoA acyl transferase.

The first step in LD formation is the synthesis of TG and CE, the major neutral lipids that compose the core of the LD. Different enzymes located in the ER are involved in their synthesis, namely diacylglycerol acyltransferases (DGAT) for TG, and acyl-CoA:cholesterol acyltransferases (ACAT) for CE. These enzymes may be activated by different stimuli including excess free fatty acids present in the medium, cell activation via surface receptors, or ER stress

[27]. The free fatty acids that are used for neutral lipid synthesis may arise from multiple sources, both exogenous (lipoproteins from blood plasma), and endogenous (destruction of intracellular membranes or stimulation of the de novo fatty acid biosynthesis)

[27].

A widely held assumption to explain the formation of LDs posits that the newly formed TG and CE accumulate in the ER. Some studies demonstrated that up to 3 mol% of TG and 5 mol% of CE can be accommodated before the LD breaks off to the cytosol, while other studies have suggested even greater accumulation, nearing 5–10% of both TG and CE. In either case, a highly regulated rate of phospholipid to neutral lipid must be maintained at all instances to support the shape and biophysical properties of the nascent organelle

[28][29][28,29].

In order to grow, nascent LDs need a positive local membrane curvature while still in the ER membrane (

Figure 1). This is achieved by the accumulation of lysophospholipids particularly lysoPA, lysoPC and lysoPE which, having a wedge-shaped conformation, help the LD to grow and counteract the neutral or slightly negative curvature produced by PC and PE, respectively

[3][25][28][29][3,25,28,29]. Since lysophospholipids are generated by phospholipase A

2s (PLA

2), this kind of enzymes, in particular cPLA

2α, are key regulators of the initial stages of LD formation

[24][30][31][32][33][24,30,31,32,33]. Of note, cPLA

2α manifests a marked selectivity for hydrolyzing phospholipids containing arachidonic acid at the sn-2 position

[34], which makes the activation of this enzyme a key regulatory event for the synthesis of arachidonate-derived bioactive eicosanoids

[35][36][37][35,36,37]. LDs have repeatedly been suggested to constitute a prominent eicosanoid-synthesizing site within the cells

[38][39][38,39]; thus, it appears that cPLA

2α may simultaneously serve two key functions of LD biology, i.e., to provide lysophospholipids to allow for continued growth of the organelle and, at the same time, to provide free AA substrate for the synthesis of bioactive lipid mediators in situ. This is further discussed in

Section 7 below.

Once a positive curve has been generated at the LD baseline, cells are now able to store more TG and CE in between the phospholipid monolayers. As a result of such enhanced accumulation of neutral lipids, a simultaneous increase in the amount of PLs is necessary to maintain the biophysical properties of the monolayer of the nascent LD. This process requires the coordinate action of enzymes from the phospholipid biosynthetic and acyl chain remodeling pathways (i.e., phospholipid:acyl-CoA acyltransferases), the latter of which contribute to remove the lysophospholipids that accumulated in the membrane as a result of PLA

2 action. As the LD emerges from the ER, a neutral curvature is established that stabilizes and protects the hydrophobic core from lipolysis

[3][12][29][3,12,29].

In the latter stages of LD biogenesis, a negative curvature is generated at the connection sites with the ER to allow for the complete cleavage and release of the newly-formed LD to the cytosol. This effect is made possible by the accumulated presence of PA at the connection sites, which promotes a strong negative curvature

[3][40][3,40]. PA is thought to be produced by phospholipase D enzymes

[41][42][41,42] and removed, as needed, by lipin-1

[16][17][16,17]. Along the whole process described above, recruitment of a wide range of accessory proteins to the LD continuously takes place, such as the aforementioned proteins of the PAT family, which help stabilize the structure and assist in the recruitment of additional proteins and lipids

[1][3][28][29][43][1,3,28,29,43].

2. Arachidonic Acid, a Compound Released in Atherosclerotic Lesions

Arachidonic acid (5,8,11,14-eicosatetraenoic acid, 20:4n-6, AA) is a member of the n-6 family of polyunsaturated fatty acids and can be obtained directly from the diet or synthesized from linoleic acid (18:2n-6) through the successive actions of Δ6-desaturase, elongase and Δ5-desaturase. Although produced mainly in the liver, practically all cells in the body are endowed with the machinery to produce AA from linoleic acid

[44][86].

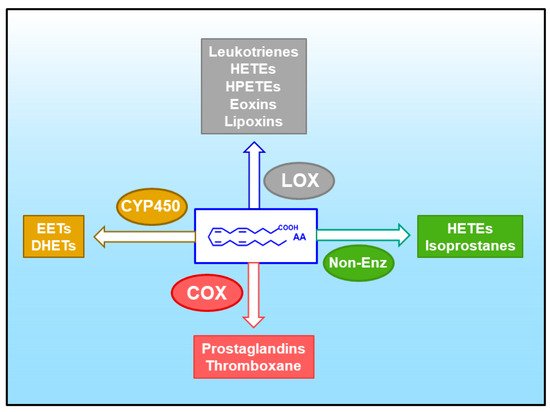

AA is the common precursor of the eicosanoids, a family of lipid mediators with key roles in physiology and especially in pathophysiological situations involving inflammatory reactions

[36] (

Figure 2). The potent biological activity of the eicosanoids requires the cells to exert a tight control on AA levels in a way that the availability of the fatty acid in free form is often a limiting factor for eicosanoid biosynthesis

[45][46][87,88]. Of note, when present at sufficiently high concentrations, AA may be significantly converted to its two-carbon elongation product, adrenic acid (7,10,13,16-docosatetraenoic acid, 22:4n-6)

[47][48][49][89,90,91], which can also be oxygenated to a variety of bioactive products

[50][51][52][92,93,94].

Figure 2. Pathways for the oxidative metabolism of AA. A variety of eicosanoids can be produced through four major pathways. These are: (i) the cyclooxygenase (COX) pathway, yielding prostaglandins and thromboxane; (ii) the lipoxygenase (LOX) pathway, yielding leukotrienes, hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acids (HETEs), hydroperoxyeicosatetraenoic acids (HPETEs), eoxins and leukotrienes; (iii) the cytochrome P450 (CYP450) pathway, yielding epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs) and dihydroxyeicosatrienoic acids (DHETEs); and (iv) non-enzymatic oxidation reactions (Non-Enz), yielding isoprostanes and HETEs.

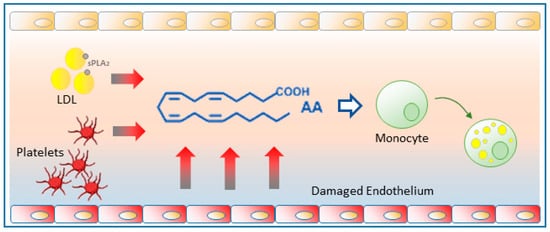

It has long been recognized that free AA is liberated in significant amounts into the bloodstream during the early stages of atherosclerosis

[53][95]. Endothelial cells activated by oxidized LDLs and other stimuli constitute a major source of free AA

[54][55][56][96,97,98]. In addition, the action of sPLA

2s released from a variety of cells directly on the LDL-bound phospholipids constitutes another important source of AA released into the bloodstream

[57][58][59][60][99,100,101,102]. Finally, platelets recruited to the activated endothelium also contribute to increase the availability of free AA

[53][95] (

Figure 3).

Figure 3. Free AA production in atherosclerotic foci. Damaged endothelium releases substantial amounts of free AA which can be taken up by circulating monocytes and promote their change to a foamy phenotype. Platelets recruited to the activated endothelium also contribute to generating free AA. The sPLA2 action on circulating LDLs can also provide significant amounts of free AA.

Increased levels of free AA in the vicinity of atherosclerotic lesions may contribute greatly to LD formation by circulating monocytes, thereby transforming them into foamy cells and hence, into pro-atherogenic monocytes. This view has been experimentally supported by data demonstrating that free AA, at pathophysiologically relevant concentrations

[61][103], is a strong inducer of LD formation in human peripheral blood monocytes

[30]. Free AA appears to serve two different roles; on the one hand it serves as a substrate for the synthesis of TG but, interestingly, not CE. Conversely, AA activates intracellular signaling via p38 and JNK-mediated phosphorylation cascades that enhance neutral lipid synthesis and also activate cPLA

2α, which in turn is required to regulate the biogenesis of the LD

[30].

LD production by monocytes exposed to AA proceeds the same in the presence of a number of cyclooxygenase or lipoxygenase inhibitors

[30]. Moreover, removal of the oxidized impurities from the commercial fatty acid (hydroxy, hydroperoxy and oxo derivatives of AA generated spontaneously) used in the above studies yielded a fraction of pure free AA that completely recapitulated LD formation in monocytes, while the oxidized AA fraction did not

[62][104]. These results demonstrate that it is free AA itself and not an oxygenated product that is responsible for inducing the conversion of monocytes into foamy cells.

Molecular analyses of the lipid composition of the LDs produced by AA in foamy monocytes has shown that the neutral lipid fractions of these cells are enriched with an uncommon positional isomer of palmitoleic acid, namely cis-7-hexadecenoic acid, (16:1n-9)

[63][75]. 16:1n-9 exhibits significant anti-inflammatory activity both in vivo and vitro which is comparable to that of n-3 fatty acids, and clearly distinguishable from that of palmitoleic acid

[63][64][75,105]. Further, 16:1n-9 can be mobilized from phospholipids in activated phagocytic cells to form novel lipid species such as 16:1n-9-containing PI molecules and esters of 16:1n-9 with various hydroxyfatty acids

[65][106]. These two kinds of compounds have been shown to possess growth-factor-like properties

[66][107] and anti-diabetic/anti-inflammatory activities

[67][108], respectively. The selective accumulation in the neutral lipid fraction of phagocytic cells of an uncommon fatty acid such as 16:1n-9 may reveal an early phenotypic change that could provide a biomarker of proatherogenicity, and a potential target for pharmacological intervention in the first stages of cardiovascular disease. Intriguingly, the 16:1n-9 fatty acid has also been recently identified in the TG fraction of some cancer cells

[68][109], suggesting perhaps a wider biological role.

3. Glycerophospholipid Hydrolysis as a Major Pathway for the Mobilization of AA

The production of lipid mediators is intrinsically linked to the availability of polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) precursors necessary for their synthesis. This depends on the activities of numerous enzymes and proteins that regulate the uptake, transport, storage, hydrolysis, remodeling and trafficking of PUFA among the different cellular and extracellular lipid pools. The major metabolic route supplying free PUFA for lipid mediator synthesis is that regulated by PLA

2s, because these enzymes can directly access the major cellular reservoir of readily mobilizable fatty acid, i.e., the sn-2 position of membrane glycerophospholipids, mainly PC, PE, and PI

[35][36][37][35,36,37]. It is relevant to indicate, however, that despite the overwhelming quantitative importance of PLA

2s to overall PUFA release, there are other minor routes not involving PLA

2 which can play important roles under limited, tightly controlled conditions. These include monoacylglycerol lipases acting on endocannabinoids

[69][70][110,111], acid lipases acting on lysosomal lipids

[71][112], and triacylglycerol lipase (ATGL) acting on TG

[72][73][113,114].

The PLA

2 enzymes typically involved in cellular signaling leading to lipid mediator production have been classically categorized into three major families, namely the Ca

2+-dependent cytosolic enzymes (cPLA

2), the Ca

2+-independent enzymes (iPLA

2), and the secreted enzymes (sPLA

2). A number of excellent comprehensive reviews covering the classification, characteristics and activation properties of the more than 30 members of the PLA

2 superfamily have recently been published, and the reader is kindly referred to these for specific details

[34][74][75][76][77][78][79][80][81][82][83][84][34,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125].

The group IVA PLA

2, or cPLA

2α, is widely recognized as the key enzyme effecting the AA release because of its unique preference for AA-containing phospholipid substrates and its activation properties, which place it at the center of a number of key signaling pathways involving phosphorylation cascades and/or intracellular Ca

2+ movements

[34][76][77][34,117,118]. In accordance, studies using cPLA

2α-deficient mice have confirmed that this enzyme is essential for stimulus-induced eicosanoid production in practically all cells and tissues

[34][74][75][76][77][34,115,116,117,118]. A myriad of stimuli, acting on surface receptors, are able to trigger the translocation activation of cPLA

2α from the cytosol to a number of intracellular membranes, including the LD monolayer

[19][20][19,20]. This allows positioning of the enzyme in the vicinity of cyclooxygenases and lipoxygenases for efficient supply of the free fatty acid for eicosanoid formation

[85][86][126,127].

The group VIA calcium-independent PLA

2, frequently referred to as iPLA

2β, is another important enzyme for lipid mediator production which, unlike cPLA

2α, does not manifest overt specificity for any particular fatty acid, being able to efficiently hydrolyze all kinds of phospholipid substrates

[87][128]. Studies in macrophages have suggested that cPLA

2α and iPLA

2β preferentially act on different membrane phospholipid subsets, the former cleaving AA-containing phospholipids, and the latter liberating other fatty acids, such as adrenic acid and palmitoleic acid

[47][48][88][89,90,129]. These in vivo preferences suggest that the activity of each PLA

2 in stimulated cells can also be limited by the nature of the stimulus, the subcellular localization of the enzyme, and the accessibility to a given phospholipid pool

[89][90][130,131].

The secreted PLA

2s (sPLA

2) constitute the third family of PLA

2 enzymes involved in lipid mediator production

[79][91][120,132]. The sPLA

2s are secreted by a variety of cells, particularly those of the innate immune system, and act mainly on extracellular substrates such as lipoproteins, microparticles, bacteria and viruses, and the outer plasma membrane of mammalian cells. In some cases, they can also be incorporated back to the cells that first released them or to neighboring cells, and act on different intracellular membrane locations to regulate innate immune responses

[92][93][94][133,134,135]. sPLA

2 enzymes often act in concert with cPLA

2α to assist and/o amplify the cPLA

2α regulated response leading to PUFA mobilization

[95][96][97][136,137,138]. However, under some circumstances, some sPLA

2s, especially those of groups IID, III, and X, elicit significant production of PUFAs and associated mediators by acting on their own on different extracellular targets, and showing certain degree of selectivity for hydrolysis of PUFA over other monounsaturated/saturated fatty acids

[98][99][100][101][139,140,141,142].

While less generally recognized, free AA levels can also be significantly increased in cells if the reacylation of lysophospholipids is inhibited

[37][45][77][102][103][104][37,87,118,143,144,145]. This is because AA is an intermediate of a reacylation/deacylation cycle, the so-called Lands cycle, where the fatty acid is hydrolyzed from phospholipids by PLA

2s and reincorporated back by CoA-dependent acyltrasferases

[37][45][37,87]. In resting cells, reacylation reactions dominate and, as a result, free AA levels in unstimulated cells are kept at very low levels. In stimulated cells, activation of cPLA

2α makes deacylation to dominate over reacylation, which results in the net accumulation of free AA. Nevertheless, AA reacylation under activation conditions is still significant, as demonstrated by the finding that a large amount of the AA initially liberated by cPLA

2α is returned back to phospholipids. Hence, blockade of the CoA-dependent acyltransferases involved in phospholipid AA reacylation can result in greatly elevated levels of the free AA which is then available for eicosanoid synthesis

[45][87]. The substrate specificity of the acyltransferases involved in AA reacylation is the reason why this fatty acid is overwhelmingly incorporated in the position sn-2 of phospholipids

[77][118].

A third layer of complexity in the regulation of free AA availability stems from the fact that, once incorporated into phospholipids, the AA does not remain in the phospholipid molecular species that initially incorporated it but moves between different phospholipid species by a series of CoA-independent transacylation reactions

[37][104][105][37,145,146]. These reactions are key for the cells to maintain the appropriate distribution of AA within the various cellular pools so that, depending on stimulation conditions, they are accessible to the relevant PLA

2 [89][90][130,131]. This is an important aspect for the regulation of eicosanoid synthesis, as the quantity and distribution of eicosanoids produced under a given condition also depends on the composition and cellular localization of the phospholipid pool where the AA-hydrolyzing PLA

2 primarily acts

[89][90][130,131].

These transacylation reactions are catalyzed by CoA-independent transacylase (CoA-IT), an enzyme that primarily transfers AA moieties from PC (diacyl species) directly to PE (both diacyl and plasmalogens species), circumventing the need for CoA or ATP

[37][104][105][37,145,146]. The sequence of CoA-IT is still unknown which has made it difficult to advance our knowledge on the cellular regulation of phospholipid transacylation. Recent studies have provided suggestive evidence that the CoA-IT-mediated reaction is primarily catalyzed by a well described PLA

2 enzyme, the group IVC phospholipase A

2γ (cPLA

2γ)

[89][105][130,146]. Unlike its homolog cPLA

2α, cPLA

2γ is a calcium-independent enzyme and does not manifest clear selectivity for AA residues

[106][147]. Since the CoA-IT reaction involving AA-containing phospholipids appears to be critically involved in the inflammatory response of macrophages to certain stimuli

[90][107][131,148], it is conceivable that other enzymes in addition to cPLA

2γ may also serve a role as CoA-IT in cells. This is currently an area of active research

[89][90][105][106][107][108][130,131,146,147,148,149].