Toxoplasmosis is a prevalent disease affecting a wide range of hosts including approximately one-third of the human population. It is caused by the sporozoan parasite Toxoplasma gondii (T. gondii), which instigates a range of symptoms, manifesting as acute and chronic forms and varying from ocular to deleterious congenital or neuro-toxoplasmosis. Toxoplasmosis may cause serious health problems in fetuses, newborns, and immunocompromised patients. Recently, associations between toxoplasmosis and various neuropathies and different types of cancer were documented. In the veterinary sector, toxoplasmosis results in recurring abortions, leading to significant economic losses. Treatment of toxoplasmosis remains intricate and encompasses general antiparasitic and antibacterial drugs. The efficacy of these drugs is hindered by intolerance, side effects, and emergence of parasite resistance. Furthermore, all currently used drugs in the clinic target acute toxoplasmosis, with no or little effect on the chronic form.

- acute toxoplasmosis

- chronic toxoplasmosis

- parasite therapeutic targets

- neuropathies

- antiparasitic drugs

- immunomodulatory drugs

1. Introduction

2. Emerging Therapeutic Targets in Toxoplasma gondii Infections

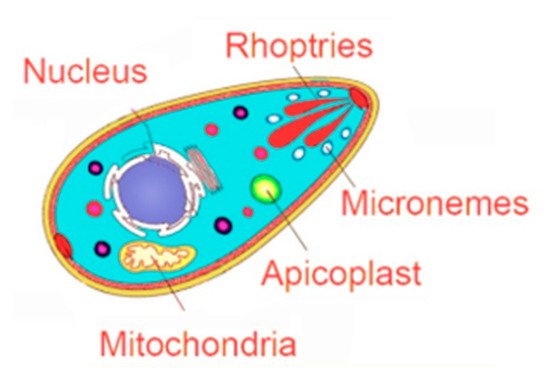

Despite all prophylactic approaches to prevent the infection with T. gondii, an available human vaccine is still out of reach. While the search for a vaccine has been highly pursued, currently used drugs target only the acute form of the disease. Chronic toxoplasmosis, which represents the more prevalent form and associates with dreadful clinical outcomes, reaching fatality in immunocompromised patients, remains an unmet medical need. An ideal drug against toxoplasmosis should affect multiple stages of the parasite life cycle (i.e., tachyzoites responsible for acute toxoplasmosis and bradyzoites responsible for chronic toxoplasmosis). Furthermore, these drugs should (1) target the parasite biology, (2) exhibit low toxicity and tolerable side effects, (3) have high bioavailability, and (4) cross the blood–brain barrier and reach the brain, where the propensity for neuronal cysts is high [81][42]. A number of preclinical studies were conducted in vitro and prolonged mice survival in vivo (reviewed in [82][43]). A comprehensive summary of tested drugs and compounds over a decade extending from 2006 to 2016 reported 80 clinically available drugs and a large number of new compounds with more than 40 mechanisms of action. Several target-based drug screens were also identified. These include different kinases, mitochondrial electron transport chain, fatty acid synthesis, DNA synthesis, and replication, among several others [59][44]. In the following sections, we will provide a comprehensive overview of the different parasite targets and their corresponding emerging drugs (Figure 1, Table 2).

| Parasite Targets | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apicoplast | Micronemes | Rhoptries | Mitochondria | Nucleus |

| Inhibitors of Fatty Acid synthesis: -Clodinafop -Thiolactomycin -Triclosan |

BKI targeting TgCDPK1: -BKI-1294 -BKI-1294 analogs: Compounds 24 and 32) -BKI-1748 |

Oxindoles | Targeting HSP60 | Topo-isomerase 2 inhibitors: -Daunorubicin -Trovafloxacin -Enrofloxacin -Gatofloxacin |

| Inhibitors of 2-Isoprenoid synthesis: -Fosmidomycin |

SP230 | 6-azaquinazolines | Atovaquone | Topo-isomerase 1 inhibitors: -Artemisinin -Artemisone -Artemiside -Artemether -Harmane -Harmine -Non-harmane |

| Inhibitors of DNA gyrase: -Quinolones -Fuoroquinolones -Ciprofloxacin -Trovafloxacin -Ofloxacin -Temafloxacin |

Pyrazolopyridines | ELQ-271 | DNA-intercalating agents: -Fluphenasine -Thioridazine -Trifluoperazine -Hycanton -Phleomycin -Mitomycin C |

|

| Inhibitors of Protein synthesis: -Clindamycin -Spiramycin -Azithromycin |

Chemical scaffolds | ELQ-316 | Ribonucleotide reductase inhibitors: -Thiosemicarbazones -Hydroxyurea |

|

| Thiazolidinone derivatives | ELQ-400 | Oxidative DNA damage/DNA binding: -Resveratrol -Valproic acid |

||

| Naphtoquinones | ||||

2.1. Targeting the Apicoplast

2.2. Targeting the Invasion Complex

2.2.1. Microneme Organelles

2.2.2. Rhoptry Organelles

2.3. Targeting the Parasite Mitochondrial Electron Transport Pathway

2.4. Targeting the Interconversion between Tachyzoites and Bradyzoites

References

- Montoya, J.G.; Liesenfeld, O. Toxoplasmosis. Lancet 2004, 363, 1965–1976.

- Ben-Harari, R.R.; Connolly, M.P. High burden and low awareness of toxoplasmosis in the United States. Postgrad. Med. 2019, 131, 103–108.

- Reza Yazdani, M.; Mehrabi, Z.; Ataei, B.; Baradaran Ghahfarokhi, A.; Moslemi, R.; Pourahmad, M. Frequency of sero-positivity in household members of the patients with positive toxoplasma serology. Rev. Esp. Quimioter. Publ. Of. Soc. Esp. Quimioter. 2018, 31, 506–510.

- Robert-Gangneux, F.; Dardé, M.-L. Epidemiology of and Diagnostic Strategies for Toxoplasmosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2012, 25, 264.

- Lindsay, D.S.; Dubey, J.P. Toxoplasma gondii: The changing paradigm of congenital toxoplasmosis. Parasitology 2011, 138, 1829–1831.

- Yamamoto, L.; Targa, L.S.; Sumita, L.M.; Shimokawa, P.T.; Rodrigues, J.C.; Kanunfre, K.A.; Okay, T.S. Association of Parasite Load Levels in Amniotic Fluid With Clinical Outcome in Congenital Toxoplasmosis. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017, 130, 335–345.

- Robbins, J.R.; Zeldovich, V.B.; Poukchanski, A.; Boothroyd, J.C.; Bakardjiev, A.I. Tissue barriers of the human placenta to infection with Toxoplasma gondii. Infect. Immun. 2012, 80, 418–428.

- McAuley, J.B. Congenital Toxoplasmosis. J. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. Soc. 2014, 3 (Suppl. 1), S30–S35.

- Singh, S. Congenital toxoplasmosis: Clinical features, outcomes, treatment, and prevention. Trop. Parasitol. 2016, 6, 113–122.

- Weiss, L.M.; Dubey, J.P. Toxoplasmosis: A history of clinical observations. Int. J. Parasitol. 2009, 39, 895–901.

- Vasconcelos-Santos, D.V.; Dodds, E.M.; Orefice, F. Review for disease of the year: Differential diagnosis of ocular toxoplasmosis. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 2011, 19, 171–179.

- Nahouli, H.; El Arnaout, N.; Chalhoub, E.; Anastadiadis, E.; El Hajj, H. Seroprevalence of Anti-Toxoplasma gondii Antibodies Among Lebanese Pregnant Women. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2017, 17, 785–790.

- Nowakowska, D.; Colón, I.; Remington, J.S.; Grigg, M.; Golab, E.; Wilczynski, J.; Sibley, L.D. Genotyping of Toxoplasma gondii by Multiplex PCR and Peptide-Based Serological Testing of Samples from Infants in Poland Diagnosed with Congenital Toxoplasmosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2006, 44, 1382.

- Galal, L.; Sarr, A.; Cuny, T.; Brouat, C.; Coulibaly, F.; Sembène, M.; Diagne, M.; Diallo, M.; Sow, A.; Hamidović, A.; et al. The introduction of new hosts with human trade shapes the extant distribution of Toxoplasma gondii lineages. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2019, 13, e0007435.

- Delhaes, L.; Ajzenberg, D.; Sicot, B.; Bourgeot, P.; Darde, M.L.; Dei-Cas, E.; Houfflin-Debarge, V. Severe congenital toxoplasmosis due to a Toxoplasma gondii strain with an atypical genotype: Case report and review. Prenat. Diagn. 2010, 30, 902–905.

- Schlüter, D.; Barragan, A. Advances and Challenges in Understanding Cerebral Toxoplasmosis. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 242.

- Blanchard, N.; Dunay, I.R.; Schlüter, D. Persistence of Toxoplasma gondii in the central nervous system: A fine-tuned balance between the parasite, the brain and the immune system. Parasite Immunol. 2015, 37, 150–158.

- Matta, S.K.; Rinkenberger, N.; Dunay, I.R.; Sibley, L.D. Toxoplasma gondii infection and its implications within the central nervous system. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 19, 467–480.

- Madireddy, S.; Rivas Chacon, E.D.; Mangat, R. Toxoplasmosis; StatPearls Publishing LLC.: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2021.

- Evans, A.K.; Strassmann, P.S.; Lee, I.P.; Sapolsky, R.M. Patterns of Toxoplasma gondii cyst distribution in the forebrain associate with individual variation in predator odor avoidance and anxiety-related behavior in male Long–Evans rats. Brain Behav. Immun. 2014, 37, 122–133.

- Hermes, G.; Ajioka, J.W.; Kelly, K.A.; Mui, E.; Roberts, F.; Kasza, K.; Mayr, T.; Kirisits, M.J.; Wollmann, R.; Ferguson, D.J.; et al. Neurological and behavioral abnormalities, ventricular dilatation, altered cellular functions, inflammation, and neuronal injury in brains of mice due to common, persistent, parasitic infection. J. Neuroinflamm. 2008, 5, 48.

- Xiao, J.; Li, Y.; Gressitt, K.L.; He, H.; Kannan, G.; Schultz, T.L.; Svezhova, N.; Carruthers, V.B.; Pletnikov, M.V.; Yolken, R.H.; et al. Severance Cerebral complement C1q activation in chronic Toxoplasma infection. Brain Behav. Immun. 2016, 58, 52–56.

- Ngô, H.M.; Zhou, Y.; Lorenzi, H.; Wang, K.; Kim, T.K.; Zhou, Y.; El Bissati, K.; Mui, E.; Fraczek, L.; Rajagopala, S.V.; et al. Toxoplasma Modulates Signature Pathways of Human Epilepsy, Neurodegeneration & Cancer. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 11496.

- Johnson, H.J.; Koshy, A.A. Latent Toxoplasmosis Effects on Rodents and Humans: How Much is Real and How Much is Media Hype? mBio 2020, 11, e02164-19.

- Johnson, S.K.; Johnson, P.T.J. Toxoplasmosis: Recent Advances in Understanding the Link Between Infection and Host Behavior. Annu. Rev. Anim. Biosci. 2021, 9, 249–264.

- Bannoura, S.; El Hajj, R.; Khalifeh, I.; El Hajj, H. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis and reactivation of cerebral toxoplasmosis in a child: Case report. IDCases 2018, 13, e00434.

- Basavaraju, A. Toxoplasmosis in HIV infection: An overview. Trop. Parasitol. 2016, 6, 129–135.

- Kodym, P.; MalÝ, M.; Beran, O.; Jilich, D.; Rozsypal, H.; Machala, L.; Holub, M. Incidence, immunological and clinical characteristics of reactivation of latent Toxoplasma gondii infection in HIV-infected patients. Epidemiol. Infect. 2015, 143, 600–607.

- Gay, J.; Gendron, N.; Verney, C.; Joste, V.; Dardé, M.L.; Loheac, C.; Vrtovsnik, F.; Argy, N.; Houze, S. Disseminated toxoplasmosis associated with hemophagocytic syndrome after kidney transplantation: A case report and review. Transpl. Infect. Dis. 2019, 21, e13154.

- Kollu, V.; Magalhaes-Silverman, M.; Tricot, G.; Ince, D. Toxoplasma Encephalitis following Tandem Autologous Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Case Rep. Infect. Dis. 2018, 2018, 9409121.

- Paccoud, O.; Guitard, J.; Labopin, M.; Surgers, L.; Malard, F.; Battipaglia, G.; Duléry, R.; Hennequin, C.; Mohty, M.; Brissot, E. Features of Toxoplasma gondii reactivation after allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation in a high seroprevalence setting. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2020, 55, 93–99.

- Ramanan, P.; Scherger, S.; Benamu, E.; Bajrovic, V.; Jackson, W.; Hage, C.A.; Hakki, M.; Baddley, J.W.; Abidi, M.Z. Toxoplasmosis in non-cardiac solid organ transplant recipients: A case series and review of literature. Transpl. Infect. Dis. 2020, 22, e13218.

- Ramchandar, N.; Pong, A.; Anderson, E. Identification of disseminated toxoplasmosis by plasma next-generation sequencing in a teenager with rapidly progressive multiorgan failure following haploidentical stem cell transplantation. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2020, 67, e28205.

- Robert-Gangneux, F.; Meroni, V.; Dupont, D.; Botterel, F.; Garcia, J.M.A.; Brenier-Pinchart, M.-P.; Accoceberry, I.; Akan, H.; Abbate, I.; Boggian, K.; et al. Toxoplasmosis in Transplant Recipients, Europe, 2010–2014. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2018, 24, 1497–1504.

- Adekunle, R.O.; Sherman, A.; Spicer, J.O.; Messina, J.A.; Steinbrink, J.M.; Sexton, M.E.; Lyon, G.M.; Mehta, A.K.; Phadke, V.K.; Woodworth, M.H. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of toxoplasmosis among transplant recipients at two US academic medical centers. Transpl. Infect. Dis. 2021, 23, e13636.

- La Hoz, R.M.; Morris, M.I.; Infectious Diseases Community of Practice of the American Society of Transplantation. Infectious Diseases Community of Practice of the American Society of Tissue and blood protozoa including toxoplasmosis, Chagas disease, leishmaniasis, Babesia, Acanthamoeba, Balamuthia, and Naegleria in solid organ transplant recipients- Guidelines from the American Society of Transplantation Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. Clin. Transplant. 2019, 33, e13546.

- Holland, M.S.; Sharma, K.; Lee, B.C. Cerebral toxoplasmosis after rituximab therapy for splenic marginal zone lymphoma: A case report and review of the literature. JMM Case Rep. 2015, 2, e005010.

- Lee, E.B.; Ayoubi, N.; Albayram, M.; Kariyawasam, V.; Motaparthi, K. Cerebral toxoplasmosis after rituximab for pemphigus vulgaris. JAAD Case Rep. 2019, 6, 37–41.

- Morjaria, S.; Epstein, D.J.; Romero, F.A.; Taur, Y.; Seo, S.K.; Papanicolaou, G.A.; Hatzoglou, V.; Rosenblum, M.; Perales, M.-A.; Scordo, M.; et al. Toxoplasma Encephalitis in Atypical Hosts at an Academic Cancer Center. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2016, 3, ofw070.

- Safa, G.; Darrieux, L. Cerebral Toxoplasmosis After Rituximab Therapy. JAMA Intern. Med. 2013, 173, 924–926.

- Rajapakse, S.; Weeratunga, P.; Rodrigo, C.; de Silva, N.L.; Fernando, S.D. Prophylaxis of human toxoplasmosis: A systematic review. Pathog. Glob. Health 2017, 111, 333–342.

- Benmerzouga, I.; Checkley, L.A.; Ferdig, M.T.; Arrizabalaga, G.; Wek, R.C.; Sullivan, W.J., Jr. Guanabenz repurposed as an antiparasitic with activity against acute and latent toxoplasmosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 6939–6945.

- McFarland, M.M.; Zach, S.J.; Wang, X.; Potluri, L.-P.; Neville, A.; Vennerstrom, J.L.; Davis, P.H. Review of Experimental Compounds Demonstrating Anti-Toxoplasma Activity. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016, 60, 7017–7034.

- Montazeri, M.; Sharif, M.; Sarvi, S.; Mehrzadi, S.; Ahmadpour, E.; Daryani, A. A Systematic Review of In vitro and In vivo Activities of Anti-Toxoplasma Drugs and Compounds (2006–2016). Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 25.

- Saremy, S.; Boroujeni, M.E.; Bhattacharjee, B.; Mittal, V.; Chatterjee, J. Identification of potential apicoplast associated therapeutic targets in human and animal pathogen Toxoplasma gondii ME49. Bioinformation 2011, 7, 379–383.

- Sonda, S.; Hehl, A.B. Lipid biology of Apicomplexa: Perspectives for new drug targets, particularly for Toxoplasma gondii. Trends Parasitol. 2006, 22, 41–47.

- Waller, R.; Keeling, P.; Donald, R.G.K.; Striepen, B.; Handman, E.; Lang-Unnasch, N.; Cowman, A.F.; Besra, G.; Roos, D.; McFadden, G.I. Nuclear-encoded proteins target to the plastid in Toxoplasma gondii and Plasmodium falciparum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 12352–12357.

- Zuther, E.; Johnson, J.J.; Haselkorn, R.; McLeod, R.; Gornicki, P. Growth of Toxoplasma gondii is inhibited by aryloxyphenoxypropionate herbicides targeting acetyl-CoA carboxylase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 13387–13392.

- Seeber, F.; Soldati-Favre, D. Metabolic pathways in the apicoplast of apicomplexa. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 2010, 281, 161–228.

- Jomaa, H.; Wiesner, J.; Sanderbrand, S.; Altincicek, B.; Weidemeyer, C.; Hintz, M.; Turbachova, I.; Eberl, M.; Zeidler, J.; Lichtenthaler, H.K.; et al. Inhibitors of the nonmevalonate pathway of isoprenoid biosynthesis as antimalarial drugs. Science 1999, 285, 1573–1576.

- Ling, Y.; Sahota, G.; Odeh, S.; Chan, J.M.; Araujo, F.G.; Moreno, S.N.; Oldfield, E. Bisphosphonate inhibitors of Toxoplasma gondi growth: In vitro, QSAR, and in vivo investigations. J. Med. Chem. 2005, 48, 3130–3140.

- Clastre, M.; Goubard, A.; Prel, A.; Mincheva, Z.; Viaud-Massuart, M.-C.; Bout, D.; Rideau, M.; Velge-Roussel, F.; Laurent, F. The methylerythritol phosphate pathway for isoprenoid biosynthesis in coccidia: Presence and sensitivity to fosmidomycin. Exp. Parasitol. 2007, 116, 375–384.

- Garcia-Estrada, C.; Prada, C.F.; Fernandez-Rubio, C.; Rojo-Vazquez, F.; Balana-Fouce, R. DNA topoisomerases in apicomplexan parasites: Promising targets for drug discovery. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2010, 277, 1777–1787.

- Maxwell, A. DNA gyrase as a drug target. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 1999, 27, 48–53.

- McFadden, G.I.; Roos, D.S. Apicomplexan plastids as drug targets. Trends Microbiol. 1999, 7, 328–333.

- Gozalbes, R.; Brun-Pascaud, M.; Garcia-Domenech, R.; Galvez, J.; Girard, P.M.; Doucet, J.P.; Derouin, F. Anti-toxoplasma activities of 24 quinolones and fluoroquinolones in vitro: Prediction of activity by molecular topology and virtual computational techniques. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2000, 44, 2771–2776.

- Khan, A.A.; Slifer, T.; Araujo, F.G.; Remington, J.S. Trovafloxacin is active against Toxoplasma gondii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1996, 40, 1855–1859.

- Reiff, S.B.; Vaishnava, S.; Striepen, B. The HU protein is important for apicoplast genome maintenance and inheritance in Toxoplasma gondii. Eukaryot. Cell 2012, 11, 905–915.

- Pfefferkorn, E.R.; Nothnagel, R.F.; Borotz, S.E. Parasiticidal effect of Clindamycin on Toxoplasma gondii grown in cultured cells and selection of a drug-resistant mutant. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1992, 36, 1091–1096.

- Dubremetz, J.; Garcia-Réguet, N.; Conseil, V.; Fourmaux, M.N. Apical organelles and host-cell invasion by Apicomplexa. Int. J. Parasitol. 1998, 28, 1007–1013.

- Langsley, G.; Heussler, V.; Chaussepied, M.; Stanway, R.R.; Lüder, C.G.K. Intracellular survival of apicomplexan parasites and host cell modification. Int. J. Parasitol. 2009, 39, 163–173.

- Portes, J.; Barrias, E.; Travassos, R.; Attias, M.; De Souza, W. Toxoplasma gondii Mechanisms of Entry Into Host Cells. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 294.

- Cardew, E.M.; Verlinde, C.L.M.J.; Pohl, E. The calcium-dependent protein kinase 1 from Toxoplasma gondii as target for structure-based drug design. Parasitology 2018, 145, 210–218.

- Murphy, R.C.; Ojo, K.K.; Larson, E.T.; Castellanos-Gonzalez, A.; Perera, B.G.; Keyloun, K.R.; Kim, J.E.; Bhandari, J.G.; Muller, N.R.; Verlinde, C.L.; et al. Discovery of Potent and Selective Inhibitors of Calcium-Dependent Protein Kinase 1 (CDPK1) from C. parvum and T. gondii. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 1, 331–335.

- Ojo, K.K.; Larson, E.T.; Keyloun, K.R.; Castaneda, L.J.; DeRocher, A.E.; Inampudi, K.K.; E Kim, J.; Arakaki, T.L.; Murphy, R.C.; Zhang, L.; et al. Toxoplasma gondii calcium-dependent protein kinase 1 is a target for selective kinase inhibitors. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2010, 17, 602–607.

- Winzer, P.; Müller, J.; Aguado-Martínez, A.; Rahman, M.; Balmer, V.; Manser, V.; Ortega-Mora, L.M.; Ojo, K.K.; Fan, E.; Maly, D.J.; et al. In Vitro and In Vivo Effects of the Bumped Kinase Inhibitor 1294 in the Related Cyst-Forming Apicomplexans Toxoplasma gondii and Neospora caninum. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 6361–6374.

- Doggett, J.S.; Ojo, K.K.; Fan, E.; Maly, D.; Van Voorhis, W.C. Bumped kinase inhibitor 1294 treats established Toxoplasma gondii infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014, 58, 3547–3549.

- Müller, J.; Aguado-Martínez, A.; Ortega-Mora, L.M.; Moreno-Gonzalo, J.; Ferre, I.; Hulverson, M.A.; Choi, R.; McCloskey, M.C.; Barrett, L.K.; Maly, D.J.; et al. Development of a murine vertical transmission model for Toxoplasma gondii oocyst infection and studies on the efficacy of bumped kinase inhibitor (BKI)-1294 and the naphthoquinone buparvaquone against congenital toxoplasmosis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2017, 72, 2334–2341.

- Schaefer, D.A.; Betzer, D.P.; Smith, K.D.; Millman, Z.G.; Michalski, H.C.; Menchaca, S.E.; Zambriski, J.A.; Ojo, K.K.; Hulverson, M.A.; Arnold, S.L.M.; et al. Novel Bumped Kinase Inhibitors Are Safe. and Effective Therapeutics in the Calf Clinical Model. for Cryptosporidiosis. J. Infect. Dis. 2016, 214, 1856–1864.

- Vidadala, R.S.R.; Rivas, K.L.; Ojo, K.K.; Hulverson, M.A.; Zambriski, J.A.; Bruzual, I.; Schultz, T.L.; Huang, W.; Zhang, Z.; Scheele, S.; et al. Development of an Orally Available and Central Nervous System (CNS) Penetrant Toxoplasma gondii Calcium-Dependent Protein Kinase 1 (TgCDPK1) Inhibitor with Minimal Human Ether-a-go-go-Related Gene (hERG) Activity for the Treatment of Toxoplasmosis. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 6531–6546.

- Vandenberg, J.I.; Perry, M.D.; Perrin, M.J.; Mann, S.A.; Ke, Y.; Hill, A.P. hERG K(+) channels: Structure, function, and clinical significance. Physiol. Rev. 2012, 92, 1393–1478.

- Rutaganira, F.U.; Barks, J.; Dhason, M.S.; Wang, Q.; Lopez, M.S.; Long, S.; Radke, J.B.; Jones, N.G.; Maddirala, A.R.; Janetka, J.W.; et al. Inhibition of Calcium Dependent Protein Kinase 1 (CDPK1) by Pyrazolopyrimidine Analogs Decreases Establishment and Reoccurrence of Central Nervous System Disease by Toxoplasma gondii. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60, 9976–9989.

- Imhof, D.; Anghel, N.; Winzer, P.; Balmer, V.; Ramseier, J.; Hänggeli, K.; Choi, R.; Hulverson, M.A.; Whitman, G.R.; Arnold, S.L.; et al. In vitro activity, safety and in vivo efficacy of the novel bumped kinase inhibitor BKI-1748 in non-pregnant and pregnant mice experimentally infected with Neospora caninum tachyzoites and Toxoplasma gondii oocysts. Int. J. Parasitol. Drugs Drug Resist. 2021, 16, 90–101.

- Débare, H.; Moiré, N.; Baron, F.; Lantier, L.; Héraut, B.; Van Langendonck, N.; Denevault-Sabourin, C.; Dimier-Poisson, I.; Debierre-Grockiego, F. A Novel Calcium-Dependent Protein Kinase 1 Inhibitor Potently Prevents Toxoplasma gondii Transmission to Foetuses in Mouse. Molecules 2021, 26, 4203.

- Hakimi, M.-A.; Olias, P.; Sibley, L.D. Toxoplasma Effectors Targeting Host Signaling and Transcription. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2017, 30, 615–645.

- Ihara, F.; Nishikawa, Y. Toxoplasma gondii manipulates host cell signaling pathways via its secreted effector molecules. Parasitol. Int. 2021, 83, 102368.

- Niedelman, W.; Gold, D.A.; Rosowski, E.; Sprokholt, J.K.; Lim, D.; Arenas, A.; Melo, M.; Spooner, E.; Yaffe, M.B.; Saeij, J.P.J. The rhoptry proteins ROP18 and ROP5 mediate Toxoplasma gondii evasion of the murine, but not the human, interferon-gamma response. PLoS Pathog. 2012, 8, e1002784.

- El Hajj, H.; Demey, E.; Poncet, J.; Lebrun, M.; Wu, B.; Galéotti, N.; Fourmaux, M.N.; Mercereau-Puijalon, O.; Vial, H.; Labesse, G.; et al. The ROP2 family of Toxoplasma gondii rhoptry proteins: Proteomic and genomic characterization and molecular modeling. Proteomics 2006, 6, 5773–5784.

- El Hajj, H.; Lebrun, M.; Arold, S.T.; Vial, H.; Labesse, G.; Dubremetz, J.F. ROP18 is a rhoptry kinase controlling the intracellular proliferation of Toxoplasma gondii. PLoS Pathog. 2007, 3, e14.

- Sinai, A.P.; Joiner, K.A. The Toxoplasma gondii protein ROP2 mediates host organelle association with the parasitophorous vacuole membrane. J. Cell Biol. 2001, 154, 95–108.

- Pernas, L.; Boothroyd, J.C. Association of host mitochondria with the parasitophorous vacuole during Toxoplasma infection is not dependent on rhoptry proteins ROP2/8. Int. J. Parasitol. 2010, 40, 1367–1371.

- El Hajj, H.; Lebrun, M.; Fourmaux, M.N.; Vial, H.; Dubremetz, J.F. Inverted topology of the Toxoplasma gondii ROP5 rhoptry protein provides new insights into the association of the ROP2 protein family with the parasitophorous vacuole membrane. Cell. Microbiol. 2007, 9, 54–64.

- Etheridge, R.D.; Alaganan, A.; Tang, K.; Lou, H.J.; Turk, B.E.; Sibley, L.D. The Toxoplasma pseudokinase ROP5 forms complexes with ROP18 and ROP17 kinases that synergize to control acute virulence in mice. Cell Host Microbe 2014, 15, 537–550.

- Behnke, M.; Fentress, S.J.; Mashayekhi, M.; Li, L.X.; Taylor, G.A.; Sibley, L.D. The polymorphic pseudokinase ROP5 controls virulence in Toxoplasma gondii by regulating the active kinase ROP18. PLoS Pathog. 2012, 8, e1002992.

- Bernstein, M.; Pardini, L.; Bello Pede Castro, B.; Unzaga, J.M.; Venturini, M.C.; More, G. ROP18 and ROP5 alleles combinations are related with virulence of T. gondii isolates from Argentina. Parasitol. Int. 2021, 83, 102328.

- Shwab, E.K.; Jiang, T.; Pena, H.F.; Gennari, S.M.; Dubey, J.P.; Su, C. The ROP18 and ROP5 gene allele types are highly predictive of virulence in mice across globally distributed strains of Toxoplasma gondii. Int. J. Parasitol. 2016, 46, 141–146.

- Rêgo, W.; Costa, J.; Baraviera, R.; Pinto, L.; Bessa, G.; Lopes, R.; Vitor, R. Association of ROP18 and ROP5 was efficient as a marker of virulence in atypical isolates of Toxoplasma gondii obtained from pigs and goats in Piaui, Brazil. Vet. Parasitol. 2017, 247, 19–25.

- Wei, F.; Wang, W.; Liu, Q. Protein kinases of Toxoplasma gondii: Functions and drug targets. Parasitol. Res. 2013, 112, 2121–2129.

- Grzybowski, M.M.; Dziadek, B.; Gatkowska, J.M.; Dzitko, K.; Dlugonska, H. Towards vaccine against toxoplasmosis: Evaluation of the immunogenic and protective activity of recombinant ROP5 and ROP18 Toxoplasma gondii proteins. Parasitol. Res. 2015, 114, 4553–4563.

- Grzybowski, M.M.; Gatkowska, J.M.; Dziadek, B.; Dzitko, K.; Długońska, H. Human toxoplasmosis: A comparative evaluation of the diagnostic potential of recombinant Toxoplasma gondii ROP5 and ROP18 antigens. J. Med. Microbiol. 2015, 64, 1201–1207.

- Behnke, M.; Khan, A.; Wootton, J.C.; Dubey, J.P.; Tang, K.; Sibley, L.D. Virulence differences in Toxoplasma mediated by amplification of a family of polymorphic pseudokinases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 9631–9636.

- Blader, I.J.; Saeij, J.P. Communication between Toxoplasma gondii and its host: Impact on parasite growth, development, immune evasion, and virulence. APMIS 2009, 117, 458–476.

- Taylor, S.; Barragan, A.; Su, C.; Fux, B.; Fentress, S.J.; Tang, K.; Beatty, W.L.; El Hajj, H.; Jerome, M.; Behnke, M.S.; et al. A secreted serine-threonine kinase determines virulence in the eukaryotic pathogen Toxoplasma gondii. Science 2006, 314, 1776–1780.

- Fentress, S.J.; Behnke, M.S.; Dunay, I.R.; Mashayekhi, M.; Rommereim, L.M.; Fox, B.A.; Bzik, D.J.; Taylor, G.A.; Turk, B.E.; Lichti, C.F.; et al. Phosphorylation of immunity-related GTPases by a Toxoplasma gondii-secreted kinase promotes macrophage survival and virulence. Cell Host Microbe 2010, 8, 484–495.

- Steinfeldt, T.; Konen-Waisman, S.; Tong, L.; Pawlowski, N.; Lamkemeyer, T.; Sibley, L.D.; Hunn, J.P.; Howard, J.C. Phosphorylation of mouse immunity-related GTPase (IRG) resistance proteins is an evasion strategy for virulent Toxoplasma gondii. PLoS Biol. 2010, 8, e1000576.

- Butcher, B.A.; Fox, B.A.; Rommereim, L.M.; Kim, S.G.; Maurer, K.J.; Yarovinsky, F.; Herbert, D.B.R.; Bzik, D.J.; Denkers, E.Y. Toxoplasma gondii rhoptry kinase ROP16 activates STAT3 and STAT6 resulting in cytokine inhibition and arginase-1-dependent growth control. PLoS Pathog. 2011, 7, e1002236.

- Chen, L.; Christian, D.A.; Kochanowsky, J.A.; Phan, A.T.; Clark, J.T.; Wang, S.; Berry, C.; Oh, J.; Chen, X.; Roos, D.S.; et al. The Toxoplasma gondii virulence factor ROP16 acts in cis and trans, and suppresses T cell responses. J. Exp. Med. 2020, 217, e20181757.

- Kochanowsky, J.A.; Thomas, K.K.; Koshy, A.A. ROP16-Mediated Activation of STAT6 Suppresses Host Cell Reactive Oxygen Species Production, Facilitating Type III Toxoplasma gondii Growth and Survival. mBio 2021, 12, e03305-20.

- Sabou, M.; Doderer-Lang, C.; Leyer, C.; Konjic, A.; Kubina, S.; Lennon, S.; Rohr, O.; Viville, S.; Cianférani, S.; Candolfi, E.; et al. Toxoplasma gondii ROP16 kinase silences the cyclin B1 gene promoter by hijacking host cell UHRF1-dependent epigenetic pathways. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2020, 77, 2141–2156.

- Simpson, C.; Jones, N.G.; Hull-Ryde, E.A.; Kireev, D.; Stashko, M.; Tang, K.; Janetka, J.W.; Wildman, S.A.; Zuercher, W.J.; Schapira, M.; et al. Identification of small molecule inhibitors that block the Toxoplasma gondii rhoptry kinase ROP18. ACS Infect. Dis. 2016, 2, 194–206.

- Molina, D.; Cossio-Pérez, R.; Rocha-Roa, C.; Pedraza, L.; Cortes, E.; Hernández, A.; Gómez-Marín, J.E. Protein targets of thiazolidinone derivatives in Toxoplasma gondii and insights into their binding to ROP18. BMC Genom. 2018, 19, 856.

- Maclean, A.E.; Bridges, H.R.; Silva, M.F.; Ding, S.; Ovciarikova, J.; Hirst, J.; Sheiner, L. Complexome profile of Toxoplasma gondii mitochondria identifies divergent subunits of respiratory chain complexes including new subunits of cytochrome bc1 complex. PLoS Pathog. 2021, 17, e1009301.

- Alday, P.H.; Doggett, J.S. Drugs in development for toxoplasmosis: Advances, challenges, and current status. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2017, 11, 273–293.

- Al-Anouti, F.; Tomavo, S.; Parmley, S.; Ananvoranich, S. The expression of lactate dehydrogenase is important for the cell cycle of Toxoplasma gondii. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 52300–52311.

- Alday, P.H.; Bruzual, I.; Nilsen, A.; Pou, S.; Winter, R.; Ben Mamoun, C.; Riscoe, M.K.; Doggett, J.S. Genetic Evidence for Cytochrome b Qi Site Inhibition by 4(1H)-Quinolone-3-Diarylethers and Antimycin in Toxoplasma gondii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017, 61, e01866-16.

- McConnell, E.V.; Bruzual, I.; Pou, S.; Winter, R.; Dodean, R.A.; Smilkstein, M.J.; Krollenbrock, A.; Nilsen, A.; Zakharov, L.N.; Riscoe, M.K.; et al. Targeted Structure-Activity Analysis of Endochin-like Quinolones Reveals Potent Qi and Qo Site Inhibitors of Toxoplasma gondii and Plasmodium falciparum Cytochrome bc1 and Identifies ELQ-400 as a Remarkably Effective Compound against Acute Experimental Toxoplasmosis. ACS Infect. Dis. 2018, 4, 1574–1584.

- Doggett, J.S.; Nilsen, A.; Forquer, I.; Wegmann, K.W.; Jones-Brando, L.; Yolken, R.H.; Bordón, C.; Charman, S.A.; Katneni, K.; Schultz, T.; et al. Endochin-like quinolones are highly efficacious against acute and latent experimental toxoplasmosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 15936–15941.

- Secrieru, A.; Costa, I.C.C.; O’Neill, P.M.; Cristiano, M.L.S. Antimalarial Agents as Therapeutic Tools against Toxoplasmosis—A Short Bridge. between Two Distant Illnesses. Molecules 2020, 25, 1574.

- Bougdour, A.; Maubon, D.; Baldacci, P.; Ortet, P.; Bastien, O.; Bouillon, A.; Barale, J.-C.; Pelloux, H.; Ménard, R.; Hakimi, M.-A. Drug inhibition of HDAC3 and epigenetic control of differentiation in Apicomplexa parasites. J. Exp. Med. 2009, 206, 953–966.

- Maubon, D.; Bougdour, A.; Wong, Y.-S.; Brenier-Pinchart, M.-P.; Curt, A.; Hakimi, M.-A.; Pelloux, H. Activity of the histone deacetylase inhibitor FR235222 on Toxoplasma gondii: Inhibition of stage conversion of the parasite cyst form and study of new derivative compounds. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010, 54, 4843–4850.

- Afifi, M.A.; Al-Rabia, M.W. The immunomodulatory effects of rolipram abolish drug-resistant latent phase of Toxoplasma gondii infection in a murine model. J. Microsc. Ultrastruct. 2015, 3, 86–91.

- Wei, S.; Marches, F.; Daniel, B.; Sonda, S.; Heidenreich, K.; Curiel, T. Pyridinylimidazole p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase inhibitors block intracellular Toxoplasma gondii replication. Int. J. Parasitol. 2002, 32, 969–977.

- Brumlik, M.J.; Pandeswara, S.; Ludwig, S.M.; Jeansonne, D.P.; Lacey, M.R.; Murthy, K.; Daniel, B.J.; Wang, R.F.; Thibodeaux, S.R.; Church, K.M.; et al. TgMAPK1 is a Toxoplasma gondii MAP kinase that hijacks host MKK3 signals to regulate virulence and interferon-gamma-mediated nitric oxide production. Exp. Parasitol. 2013, 134, 389–399.

- Brumlik, M.J.; Wei, S.; Finstad, K.; Nesbit, J.; Hyman, L.E.; Lacey, M.; Burow, M.E.; Curiel, T.J. Identification of a novel mitogen-activated protein kinase in Toxoplasma gondii. Int. J. Parasitol. 2004, 34, 1245–1254.

- Sun, H.; Zhuo, X.; Zhao, X.; Yang, Y.; Chen, X.; Yao, C.; Du, A. The heat shock protein 90 of Toxoplasma gondii is essential for invasion of host cells and tachyzoite growth. Parasite 2017, 24, 22.

- Lyons, R.E.; Johnson, A.M. Heat shock proteins of Toxoplasma gondii. Parasite Immunol. 1995, 17, 353–359.

- Toursel, C.; Dzierszinski, F.; Bernigaud, A.; Mortuaire, M.; Tomavo, S. Molecular cloning, organellar targeting and developmental expression of mitochondrial chaperone HSP60 in Toxoplasma gondii. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2000, 111, 319–332.

- Dobbin, C.A.; Smith, N.C.; Johnson, A.M. Heat shock protein 70 is a potential virulence factor in murine toxoplasma infection via immunomodulation of host NF-kappa B and nitric oxide. J. Immunol. 2002, 169, 958–965.

- Ashwinder, K.; Kho, M.T.; Chee, P.M.; Lim, W.Z.; Yap, I.K.S.; Choi, S.B.; Yam, W.K. Targeting Heat Shock Proteins 60 and 70 of Toxoplasma gondii as a Potential Drug Target.: In Silico Approach. Interdiscip. Sci. 2016, 8, 374–387.