Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Po Shiuan Hsieh and Version 3 by Jessie Wu.

The objective of this rentryview is to present an update on the link between chemokines and obesity-related inflammation and metabolism dysregulation under the linght of recent knowledge, which may present important therapeutic targets that could control obesity-associated immune and metabolic disorders and chronic complications in near future. In addition, the cellular and molecular mechanisms of chemokines and chemokine receptors including the potential effect of post-translational modification of chemokines in ther regulation of inflammation and energy metabolism will be discussed in this entryreview.

- chemokines

- inflammation

- energy metabolism

- obesity

1. Chemokines in Obesity and Metabolic Syndrome

The increase in prevalence of obesity and associated cardiometabolic diseases has become a priority issue in health care systems worldwide and contributes to the global economic burden. Adipose tissue expansion in obesity consists of white and brown adipose tissues. WAT is the predominant site of energy storage and also serves as the endocrine organ. The adipocyte-derived hormones, cytokines and growth factors could regulate cell functions on local and/or systemic levels. Brown adipose tissue (BAT) is rich in mitochondria and capable of increasing energy expenditure and adaptive thermogenesis mainly via the activity of uncoupling protein 1 (UCP-1) [1][8]. There are some subcutaneous WATs possessing a subset of cells called beige adipocytes that can express high levels of UCP-1 upon chronic exposure to cold and β-adrenergic stimulation. Thereby, these cells are capable of elevated fuel oxidation and thermogenesis if needed. On the other hand, the chemokine levels in adipose tissue could be upregulated by the augmentation of inflammatory mediators in the obese adipose tissues [2][3][4][9,10,11]. However, it still remains elusive about the role of chemokines in deteriorating the development of adipose tissue dysfunction and insulin resistance in humans.

Previous reports have demonstrated that chemokines can facilitate the development of morbid obesity through its receptors to promote inflammatory leukocyte influx, especially pro-inflammatory monocytes, into hypertrophic adipose tissue. Circulating levels and tissue contents of the chemokines such as CXCL1, CXCL5, CXCL8, CXCL12, CCL2, CCL5, CCL7 and CCL19 are significantly increased in obesity. Abrogation of the signal pathways of CXCL14, CXCL5, CCL2, or their cognate chemokine receptors, alleviated obesity-associated metabolic abnormalities in high fat diet (HFD)-induced obese mice [5][6][1,12]. For instance, the study conducted with HFD-induced obese mice showed that deletion of CCL2 or its receptor CCR2 significantly attenuated inflammatory macrophage (ATM) infiltration and inflammatory reaction in adipose tissues [7][8][9][13,14,15] and consistent overexpression of CCL2 in adipose tissue increased inflammatory ATM content in WAT [10][16]. Nevertheless, deletion of CCL2 gene did not affect obesity-associated monocyte influx into WAT [11][17]. On the other hand, previous reports have demonstrated that the increases of the expression CCL7 [12][18] in adipose tissues not only promotes migration of prostate cancer cells but also participates in a link between adipose tissue inflammation and insulin resistance in HFD-induced obese mice and the murine 3T3-F442A pre-adipocyte cell line. Increased adipose tissue expression of CCL19 in obese subjects has also been implicated to represent a pathological link between systemic low-grade inflammation and insulin resistance [13][19]. Taken together, these observations demonstrate that the chemokines/chemokine receptor-mediated signaling substantially contribute to the development of adipose tissue inflammation and subsequent metabolic disorders in obesity. However, the dualistic role of chemokines and chemokine receptors in the etiology of obesity-related inflammation and energy metabolism has been speculated on, but the data remain ambiguous.

2. The Involvement of Chemokines and Chemokine Receptors in the Development of Inflammation and Energy Metabolism

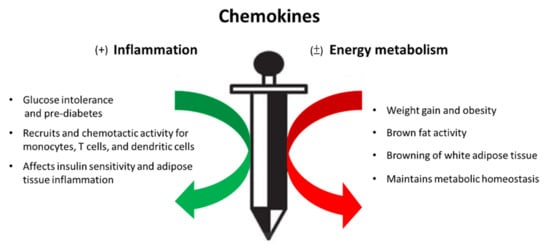

Metabolism homeostasis has been believed to be affected by cytokines secreted by immune cells as well as by adipocytes themselves in adipose tissue. Augmentation of tissue inflammation through adipocyte release of chemokines (e.g., CCL2 [7][13], CCL5 [14][20]) drives the alteration in leukocyte number and phenotype, thereby expanding the inflammatory environment within adipose tissue beds. The pro-inflammatory signals are also the important components of the thermogenic regulation in brown and beige adipocytes and contribute to their dysfunction in obesity by impairing energy expenditure and glucose uptake. In contrast, brown adipocytes release chemokines such as CXCL14- recruited, alternatively activated (M2) macrophages, and exerts its effects on promoting energy metabolism [15][21]. It is implicated that chemokines and chemokine receptors play a double-edged role in the progression of adipose tissue inflammation and energy metabolism, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Chemokines, a double-edged sword in the inflammatory response and energy metabolism during the process of metabolic syndrome.

2.1. CCL5

CCL5, also known as RANTES, has been documented to be involved in the pathogenesis of many inflammatory conditions in vivo. CCL5 could activate downstream signaling pathways such as nuclear factor NF-κB, and mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways through its receptors, namely, CCR1, CCR3, and CCR5 [16][17][18][22,23,24]. In diabetes patients, CCL5 and CCR5 are upregulated in the peripheral blood [19][20][25,26] and they have also been well-documented as the upstream regulators of insulin resistance in obese individuals [21][27]. Besides, the increased serum levels of CCL5 in type 2 diabetic patients were closely related to postprandial hyperglycemia [22][28]. The onset of cardiovascular diseases in middle-aged females has been shown to be correlated to the CCL5 level in adipose tissue [23][29]. Augmented expression of CCL5 has been demonstrated to mediate the arrest and transmigration of monocytes/macrophages into the damaged site by binding with its receptor CCR5 [18][24][25][24,30,31]. CCL5 has also been reported to be involved into inflammatory reaction of WAT by recruiting blood monocytes and exerting antiapoptotic properties on WAT macrophages in obese subjects [14][20]. Moreover, Kim et al. reported that UV-induced CCL5 can suppress triglyceride synthesis in human adipocytes via downregulation of lipogenic enzymes. These observations suggest that CCL5 may participate in the pathogenesis of obesity-associated dysregulation of lipid metabolism and comorbidities [26][32].

On the other hand, CCL5 has also been reported to participate in the central control of energy metabolism in addition to their roles in mediating inflammation. Chou and colleagues showed that the hypothalamic CCL5/CCR5 signaling through the regulation of glucose uptake and AMPK activity might link to systemic insulin dependent glucose metabolism [27][33]. Furthermore, a clinical study evaluated the expression changes of CCL5 and CCR5 in obese humans under physical exercise. Their result showed that expression of CCL5 and CCR5 was higher in the subcutaneous adipose tissue of obese individuals compared with lean control and the elevated expression of CCL5 and CCR5 was significantly reversed through physical exercise [28][34]. Our recent study has demonstrated that obesity-induced augmentation of CCL5/CCR5 signaling suppressed adaptive thermogenesis by inhibiting AMPK-mediated lipolysis and oxidative metabolism in BAT to deteriorate the development of obesity [29][35]. However, the role of the CCL5-mediated signaling and whole-body energy metabolism still needs to be clarified further.

2.2. CX3CL1-CX3CR1 Signaling

CX3CL1, also known as fractalkine, is a chemokine with chemotactic activity for monocytes, T cells, and NK cells in the development of numerous inflammatory conditions in obesity-associated chronic complications such as atherosclerosis, insulin resistance and Type 2 diabetes [30][31][32][36,37,38]. For instance, the elevated CX3CL1 level has been reported in the blood of patients with type 2 diabetes and obesity [31][37]. CX3CL1 has been demonstrated to promote monocyte adhesion to human adipocytes as well as to evoke adipose tissue inflammation [31][37]. A study has shown that CX3CL1-mediating early recruitment of microglia induced by HFD might contribute to the induction of hypothalamic inflammatory response and subsequently the impairment of glucose tolerance and adiposity in experimental obesity [33][39]. Nevertheless, the role of the CX3CL1-CX3CR1 system in obesity-associated adipose tissue inflammation and insulin resistance remains controversial. For instance, CX3CR1 deficient mice were protected against the development of HFD-induced obesity and WAT inflammation [34][40]. Deficiency of CX3CL1-CX3CR1 signaling resulted in the reduction of M2-polarized macrophage migration and an M1-dominant shift of macrophages within WAT. Moreover, mice lacking CX3CR1 expression with HFD feeding displayed the reduced expression of proinflammatory cytokines and improved the profile of proteins involved in lipid metabolism and thermogenesis in BAT [35][41]. However, CX3CL1 administration in vivo has been reported to have a contradictory effect in diminishing glucose intolerance and insulin resistance [36][42]. Lee and colleagues also showed that CX3CR1−/− mice developed glucose intolerance with diminished insulin secretion on both regular chow and HFD. CX3CR1 deletion also promoted proinflammatory macrophage accumulation in adipose tissue and liver as well as insulin resistance [32][38]. Moreover, Nagashimada et al. reported that glucose intolerance, insulin resistance, and hepatic steatosis induced by HFD-induced obesity or leptin deficiency were exacerbated in CX3CR1−/− mice. Thus, these contradictory observations implicate the dualistic role of the CX3CL1-CX3CR1 signaling in obesity-associated dysregulated glucose metabolism and adipose tissue inflammation. However, the underlying mechanism remains unclear.

2.3. CXCL12-CXCR4 Signaling

CXCL12, also known as stromal cell-derived factor 1 (SDF1), initially is a chemokine identified in bone marrow-derived stromal cells [37][43] and also an adipocyte-derived chemokine [38][44]. CXCL12 could regulate cell migration and survival through its receptor CXCR4 during cell development and tissue re-modeling [39][45]. Furthermore, blockage of CXCL12 action could reduce macrophage accumulation in adipose tissue via its receptor CXCR4 and eventually improved systemic insulin resistance in mice [38][44]. The CXCR4 in WAT has been reported to contribute to obesity-induced leukocyte recruitment, homeostasis, adipose tissue inflammation, and functional responses of adipocytes [40][41][46,47]. Moreover, the CXCL12-CXCR4 pathway has recently been speculated to be involved in the regulation of energy metabolism. For example, CXCL12-CXCR4 axis in adipose progenitors (APCs) has been demonstrated to contribute to ectopic fat deposition in high-fat fed mice through their migration to skeletal muscle to differentiate into adipocytes from subcutaneous fat [42][48]. Pharmacological antagonism of CXCR4 could prevent the effect of CXCL12 on APCs in subcutaneous fat and mimic the effects of overfeeding. A study conducted with CXCR4 Loxp mouse and fatty acid-binding protein 4 -Cre mice has shown that CXCR4 deficiency in either adipocyte or myeloid leukocyte could facilitate body weight gain and adiposity in HFD-induced obese mice through enhancing macrophage infiltration into the WAT and hypo-activity of brown adipocytes [40][46]. Accordingly, the UCP-1 mRNA and protein levels and oxygen consumption were significantly increased in the brown adipocytes treated with CXCL12 peptide [43][49]. In addition, the CXCL12-CXCR4 pathway has been further shown to participate in the control of adaptive thermogenesis and metabolic homeostasis through the activation of brown adipocytes in response to over-nutrition or intake of HFD [43][49]. In brief, the CXCL12-CXCR4 pathway could potentially affect several physiological processes related to the regulation of energy metabolism in adipose tissues.

2.4. CXCL14

The enhanced expression of CXCL14 was noted in WAT of HFD-fed obese mice. CXCL14 deletion could reduce proinflammatory macrophage infiltration in WAT and improved insulin sensitivity in HFD-fed female mice [44][50]. CXCL14 deficiency could diminish HFD-induced hyperglycemia, hyperinsulinemia, hypo-adiponectinemia and hepatic steatosis in mice [44][45][50,51]. In addition, overexpression of CXCL14 in skeletal muscle restored obesity-induced insulin resistance in CXCL14−/− mice [44][46][50,52]. It is implicated that CXCL14 is important not only in the regulation of insulin-dependent glucose uptake in skeletal muscles but also in control of whole-body glucose metabolism. Nevertheless, the in vitro study has also shown that CXCL14 has the pro-diabetogenic effects to inhibit glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in mouse islets [47][53].

Intriguingly, a research team found a causal link between CXCL14 protein and the regulation of energy metabolism. In their study, thermogenic stimuli led to the increase in CXCL14 levels and also the release of CXCL14 by BAT, which exhibits potential beneficial effects to obesity-associated metabolic diseases such as metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes. In addition, the authors have further demonstrated that CXCL14 might have a protective effect against insulin resistance by promoting the recruitment of alternatively activated M2 macrophages to adipose tissues and subsequently promote brown fat activity and white fat browning in subcutaneous adipose tissue [15][21]. However, there was a contradictory report that HFD-induced upregulation of CXCL14 could enhance insulin sensitivity by affecting adipocyte insulin signaling [48][54].