Human skeletal remains are considered as real biological archives of each subject’s life. Generally, traumas, wounds, surgical interventions, and many human pathologies suffered in life leave identifiable marks on the skeleton, and their correct interpretation is possible only through a meticulous anthropological investigation of skeletal remains. The study here presented concerns the analysis of a young Slavic soldier’s skeleton who died, after his imprisonment, in the concentration camp of Torre Tresca (Bari, Italy), during the Second World War (1946). In particular, the skull exhibited signs of surgical activity on the posterior cranial fossa and the parieto-occipital bones. They could be attributed to surgical procedures performed at different times, showing various degrees of bone edge remodeling. Overall, it was possible to correlate the surgical outcomes highlighted on the skull to the Torkildsen’s ventriculocisternostomy (VCS), the first clinically successful shunt for cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) diversion in hydrocephalus, which gained widespread use in the 1940s. For this reason, the skeleton we examined represents a rare, precious, and historical testimony of an emerging and revolutionary neurosurgical technique, which differed from other operations for treating hydrocephalus before the Second World War and was internationally recognized as an efficient procedure before the introduction of extracranial shunts.

1. Introduction

The skeleton is a true biological archive because it faithfully testifies an individual’s state of health and relationship with the environment.

Surgical procedures undergone in life, autopsies and anatomical preparations/dissection can all leave clearly identifiable marks on human skeletal remains

[1]. However, the distinction between them for scientific research can be challenging. For these reasons, it is firstly very important to distinguish ante-mortem interventions from post-mortem ones

[2][3][2,3].

Among ante-mortem interventions, the trepanation of the skull arouses a particular forensic and anthropological interest, being regarded as one of the oldest known surgical procedures and having been reported in numerous prehistoric and archaic societies

[4][5][4,5]. A thorough differential diagnosis is essential in these cases, especially in a skull lacking medical history or coming from an archaeological context where there is no other evidence that such operations were performed. Thus, identification of unhealed drilling (identifiable in cases where death has occurred soon after the procedure) is relatively straightforward, since tool marks provide direct evidence of surgical intervention. Conversely, a confident diagnosis is more difficult in healed defects of the skull, where bone remodeling that occurred during the survival time may hide the original surgical marks

[6][7][8][6,7,8].

Exceptionally, however, anthropological investigations of human skeletal remains allow us to highlight signs of surgical procedures whose morphological pattern is so characteristic that it can be precisely attributable to specific techniques.

Here we describe the skeletal remains of a Slavic soldier who died at the age of 21 years, whose skull shows signs of antemortem neurosurgery procedures morphologically comparable to the Torkildsen’s ventriculocisternostomy (VCS)

[9]. The skeletonized individual (stored in a coffin marked with the number 33 and bearing the years of birth and death “1925–1946”) is part of a skeleton collection of Slavic troops who had been detained and died in the prison camp of Torre Tresca (Bari Italy) during the Second World War, and whose remains were found in the Ossuary of the Monumental Cemetery of Bari

[10][11][10,11].

2. Materials and Methods

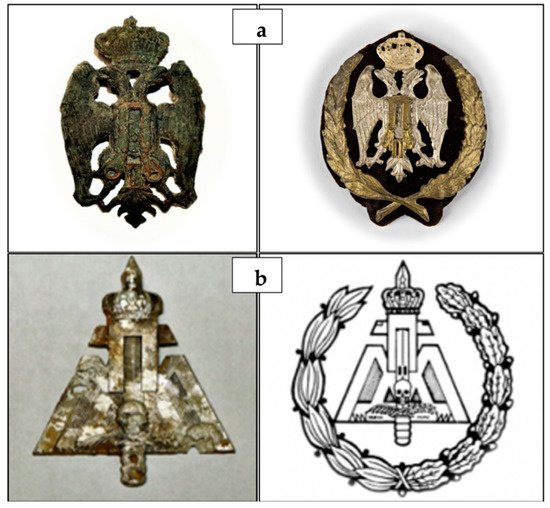

The examined subject is one of the 93 Slavic soldier skeletal remains from the Ossuary of the Monumental Cemetery of Bari. Several historical documents and the objects placed in the coffins allowed us to establish that the skeletons belonged to soldiers of the Yugoslav-Chetnik Royal Army, who were exiled to Italy in 1941 following the Yugoslavian invasion by the Axis powers. In particular, near the Slavic soldier skeletal remains contained in the coffin numbered 33, we found the frieze of the Royal Yugoslav Army, bearing the monogram of Peter II Karađorđević (last King of Yugoslavia between 1934 and 1945), which soldiers usually wore on a pointed sheepskin hat. Moreover, we found the military badge of Ravnogorksi, representing the movement’s struggle of Ravna Gora, where the Slavic troops to whom the skeletal collection belongs, were under General Dragoljub Draža Mihailović’s leadership (

Figure 1).

Figure 1. Objects placed in coffin No. 33. Frieze of the Royal Yugoslav Army, bearing the monogram of Peter II Karađorđević (a), and military badge of Ravnogorksi, representing the movement’s struggle of Ravna Gora under the leadership of General Dragoljub Draža Mihailović (b).

3. Results

The skeleton under examination belonged to a man with an age-at-death of 20–25 years, height 174.4 ± 3.3 cm. Osteometric measurements indicated a mesocranial skull, with a horizontal cranial index of 75.0–79.0. The presence of the metopic suture was detected. The platimeric index of the femur, with a value of 103, indicated stenomeria, suggesting a poor development of trochanters. The robustness index calculation resulted in a value of 11, indicating a weak femur, while the pilastric index was equal to 75, suggesting a weak activity of the thigh muscle of the subject in life. The cnemic index of the tibia, with a value of 134, indicated eurychnemia, which is suggestive of poor muscular development (calf muscle).

During paleopathological analyses, a cribra orbitalia of severity 3 and healing grade 1 was found on both the left and right orbital roof

[12][26], suggesting that the subject probably suffered an iron deficiency, or infectious disease, or scurvy, or B12 deficiency megaloblastic anemia

[13][27], or that he developed a hematological disease causing a hemopoietic marrow expansion

[14][28].

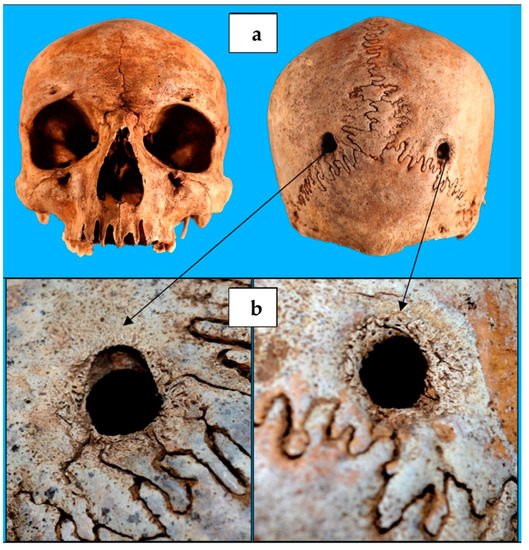

Investigation for any traumatic lesions revealed the presence of two cranial circular holes (

Figure 2), each with a diameter of 1 cm, and located at the level of the parietal bones, near the meeting point between the sagittal suture and the lambdoid one. They were specularly positioned along an almost transversal axis, and they had margins with traces of bone remodeling, allowing us to establish that the two holes’ production occurred antemortem

[15][16][17][23,29,30].

Figure 2. Cranium of the individual contained in coffin No. 33. (

a) The two circular-shaped lesions of parietal bones, (

b) with evidence of a healing process along their edges.

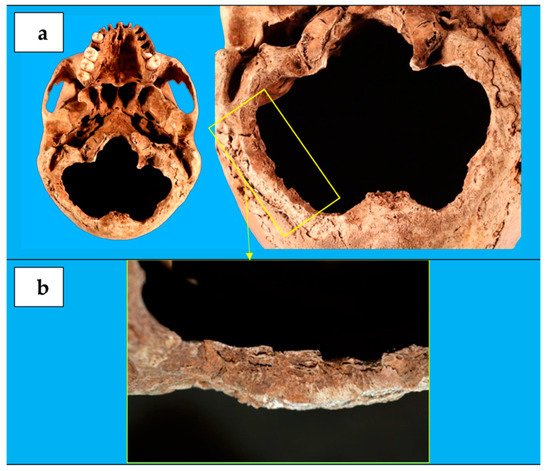

The most significant skull lesion consisted in a loss of substance in the occipital bone lower portion (

Figure 3), resulting in an occipital foramen enlargement. It was clover-shaped, with a transverse diameter of 10 cm and an antero-posterior diameter of 8 cm. Its margins run along the occipito-mastoid sutures bilaterally and between the upper nuchal line and the lower one at the rear, lapping the outer occipital protuberance. Typical cutting blade marks were still observable over part of the lesion edges, showing a poorly evident healing process and suggesting that the lesion had been probably produced later than the paralambdoid ones

[2].

Figure 3. (

a) The clover-shaped loss of substance in the occipital bone lower portion, (

b) with cutting blade marks over part of the lesion edges and poorly evident healing process.