1. Insulin Resistance as Trigger Event for NAFLD Onset, Progression, and Clinical Course

NAFLD is recognized as a heterogenous disease, with disparate and complex causes of liver dysfunction

[1]. Various maladaptations along with genetic influences are thought to be responsible for NAFLD onset and progression. The disease is therefore increasingly termed metabolic dysfunction associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD)

[1]. Chronic subclinical inflammation and IR are considered as most significant molecular drivers of NAFLD/MAFLD progression

[2][3][4][4,16,17]. Due to the potential risk of leading to liver fibrosis/cirrhosis this can determine patient prognosis

[5][6][7][8][9][10][18,19,20,21,22,23]. NAFLD/MAFLD is related to renal and cardiovascular disease, whereby obesity and T2D are delineated as main pathologies linking NAFLD/MAFLD with long term sequelae

[11][12][13][14][15][16][24,25,26,27,28,29]. Furthermore, metabolic fatty liver disease is a predictor of colorectal adenoma, related to the incidence of various malignancies, and in particular to the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)

[8][9][17][18][19][21,22,30,31,32]. In the US, metabolic fatty liver disease is currently the second leading etiology of HCC-related liver transplantation and patients undergoing major surgery have more perioperative complications and longer hospital stay. After transplantation there is a significant risk of de novo T2D and NAFLD/MAFLD, and furthermore of premature death from cardiovascular complications and sepsis

[20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27][33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40]. Together, MAFLD/NAFLD has to be considered a multisystem disease, as hepatic manifestation of the metabolic syndrome (MeSy)/T2D and can influence patient prognosis

[26][28][29][39,41,42].

IR is the early pathophysiologic trigger event in the overnutrition-MeSy-T2D spectrum (

[30][43]; reviewed in

[31][44]). IR is closely related to ectopic lipid deposition, whereby liver fat is recognized as central predictor of whole-body insulin sensitivity, or reciprocally IR under human in vivo conditions

[2][30][31][32][33][4,43,44,45,46]. The metabolic condition of skeletal muscle, the organ system most evidently impacted by physical exercise, was recently found to be influenced by liver lipid status in a dose dependent fashion

[33][46]. Regular physical exercise can favorably modulate whole-body IR and improve glucose control and life expectancy of T2D subjects

[34][47]. Therefore, guidelines on T2D management suggest regular physical activity as one causal treatment option

[35][36][48,49]. This treatment strategy could also exert beneficial effects under conditions of NAFLD/MAFLD

[37][50]. Current guidelines on the clinical management of metabolic fatty liver disease include such recommendations, although evidence is sparse and potential underlying molecular mechanisms are fragmentarily understood

[38][51].

2. The Concept of Metabolic Flexibility: Molecular Mechanisms of Physical Activity on Glucose Metabolism and Insulin Signaling in Skeletal Muscle

The concept of metabolic flexibility is defined by the ability to rapidly adapt to conditional changes in energetic substrate demand, as for instance with transition from feeding to the fasted state, or acute onset of physical activity

[39][40][41][42][52,53,54,55]. It was shown in the 1990s that postabsorpive IR humans expose markedly reduced skeletal muscle fatty acid oxidation, a state termed metabolic inflexibility

[43][56]. Although evidence in this field has enormously grown in past decades it remains established that IR is a key component of metabolic inflexibility (reviewed in

[41][54]). IR is clinically relevant mainly in white adipose tissue (WAT), skeletal muscle, and the liver. A broad body of evidence is available regarding the numerous molecular mechanisms responsible for the development of IR, to which the interested reader is referred

[44][45][57,58]. Selected aspects in skeletal muscle, which can be modified by physical activity, will be in scope of this paragraph.

Skeletal muscle accounts for 60–80% of insulin stimulation-mediated glucose metabolism

[46][59]. Rising skeletal muscle metabolic activity by means of physical exercise therefore constitutes a promising therapeutic approach. Multiple mechanisms are discussed with regards to acute or chronic exercise training on insulin action and related substrate flux

[47][48][49][50][51][52][53][60,61,62,63,64,65,66].

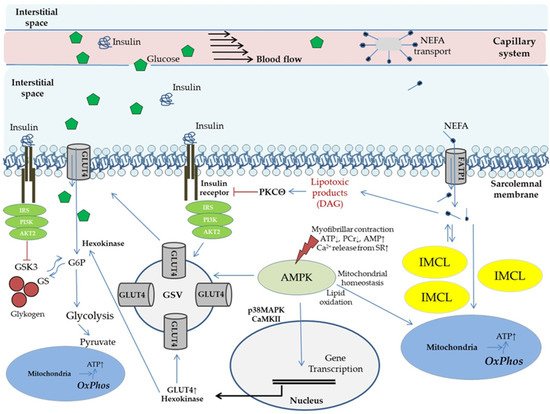

Figure 1 provides an overview.

Figure 1. Potential molecular mechanisms of physical exercise and lipid species on glucose uptake and modulation of insulin action in skeletal muscle (conducted according to

[44][50][51][53][54][55][56][57,63,64,66,67,68,69]). Physical exercise basically modulates supply of substrates and signaling molecules (via enhanced capillary perfusion, capillary recruitment/expansion of capillary volume); membrane transport of glucose (effects are majorly reported for GLUT4); mitochondrial adaptations (mitochondrial plasticity) and metabolic activation (glycolysis, lipid metabolism); and storage capacity and mobilization of energetic substrates (glycogen, IMCL). Effects of physical activity on insulin action and glucose uptake mediated by activation of AMP-activated protein kinase have been evaluated in various clinical settings (reviewed in

[31][44]). AKT2, gene 2 encoding proteinkinase B; AMPK, AMP-activated protein kinase; CaMK, calcium/calmodulin kinase; DAG, diacylglycerol; FATP, fatty acid transport protein; G6P, glucose 6 phosphate; GLUT, glucose transporter; GS, glycogen synthase; GSK, glycogen synthase kinase; GSV, glucose transporter storage vesicle; IRS, insulin receptor substrate; IMCL, intramyocellular lipids; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; NEFA, non-esterified fatty acids; OxPhos, oxidative phosphorylation; PCr, phosphocreatine; PI3K, phospho-inositol 3 kinase; PKC, proteinkinase C; SR, sarcoplasmic reticulum.

Hallmarks of peripheral IR are impaired glucose transporter 4 (GLUT4) mediated glucose uptake by skeletal muscle, and compromised suppressibility of WAT lipolysis (reviewed in

[31][44]). Visceral obesity is common in IR subjects and extensive evidence implicates that elevated circulating non-esterified fatty acids (NEFA) from inappropriate WAT hyperlipolysis are contributing to the etiology

[4][57][58][17,70,71]. Under hyperlipolytic conditions increased proportions of NEFA are taken up by skeletal muscle. As indicated in

Figure 1 this is followed by a rise in diacylglycerol (DAG), a product exerting potential lipotoxic effects on insulin signal transduction, resulting in reduced insulin stimulated GLUT4 translocation

[4][51][17,64]. Supporting this, in vivo experimental settings in humans have shown that increased NEFA exposure of skeletal muscle reduces both, non-oxidative and oxidative glucose metabolism, as mirrored by 50% reduced glucose oxidation rates and glycogen storage capacity, respectively

[45][59][60][58,72,73]. Furthermore, “NEFA overflow” under IR conditions is related to a rise in intramyocellular lipid (IMCL) deposition, which could play a role in buffering NEFA influx

[45][58]. IMCL, particularly the depots in the subsarcolemmal region, correlate with the presence of IR under in vivo conditions in obese subjects, and are associated with cellular DAG and ceramide levels

[61][62][63][74,75,76]. IMCL elevation is hypothesized to result not alone from increased lipid uptake, but also from impaired mitochondrial function. Experimental research supports this hypothesis, showing that skeletal muscle overexpression of the human catalase gene to mitochondria protects from age-related mitochondrial dysfunction and lipid-induced IR

[64][77]. A role for mitochondrial dysfunction is further supported by findings in young lean and normoglycemic subjects with diabetic parents, exposing a 60% increase in IMCL along with a 38% reduced mitochondrial density, and 60% diminished insulin stimulated glucose uptake

[65][78]. Knowledge on IMCL was just recently expanded by showing that contribution of IMCL to whole-body lipid oxidation could decrease in an obesity dependent manner

[63][76]. Interestingly, lean old and young subjects had comparable IMCL, while old obese subjects had more than twofold greater IMCL and were more IR. The authors of this study suggest that skeletal muscle IR and lipid accumulation are likely due to lifestyle factors rather than inherent ageing of skeletal muscle

[63][76]. Remarkably, normal weight endurance trained athletes also have higher IMCL levels with concomitantly increased muscle DAG, but are at the same time more insulin sensitive as compared to sedentary normal weight and obese subjects (“athlete’s paradox”)

[61][74]. In that regard it is known that muscle contractions, comparable to insulin stimulation, can increase DAG levels in skeletal muscle cells and potentially play a role in adaptations induced by exercise

[66][67][68][79,80,81]. Therefore, regular physical exercise could not alone normalize DAG related metabolism, but also impact specific proteins involved in subcellular IMCL formation and mobilization. Moreover, physical training appears to improve (or maybe even preserve) mitochondrial function, mediated at least in part by AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK)

[53][56][61][62][66,69,74,75]. The latter phenomenon is of specific interest in the discussion according to NAFLD/MAFLD, since it was shown by Michael Rodens’ group in humans in vivo that patients suffering from NASH have substantial mitochondrial dysfunction despite higher mitochondrial mass, resulting in impaired metabolic flexibility

[69][82]. It is well known that IR correlates with mitochondrial function, even in skeletal muscle

[70][83]. Otherwise, beneficial effects of regular exercise on mitochondrial plasticity are recognized

[71][72][84,85]. For instance, rigorous physical exercise under specific conditions just over few weeks was lately shown to improve muscle mitochondrial volume density by as much as 50% and citrate synthase activity by 40%

[73][86]. Consequently, mitochondrial dysfunction can be defined as central pathology related to IR and ectopic lipid accumulation, while physical activity can be interpreted as a potent treatment option to restore or at least preserve metabolic flexibility. Remarkably, not only endurance training, but also resistance exercise can exert favorable adaptions on ectopic lipid metabolism

[74][75][87,88].

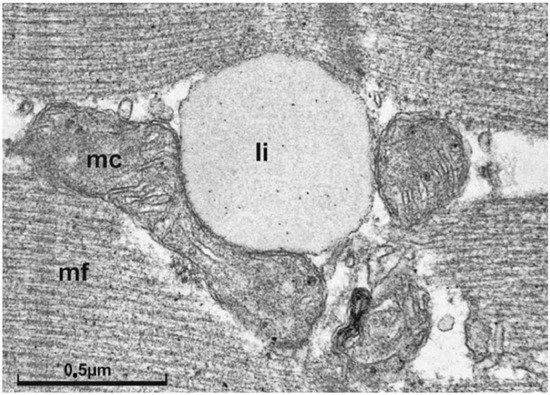

Figure 2 shows a representative IMCL droplet in skeletal muscle of a trained subject. The close spatial relationship of IMCL and mitochondria could be indicative of a “logistic adaptation”, to be able to quickly respond to increased substrate demand.

Figure 2. Electron micrograph of a longitudinal section of skeletal muscle tissue. In the center, at the z-line level, interfibrillar mitochondria with a lipid droplet immediately adjacent are shown (micrograph taken from

[76][89] with kind permission of

[77][90] and Springer-Nature). In support of the concept of metabolic flexibility it is believed that greater IMCL storage capacity in athletes represents an adaptive response to regular physical training, allowing a larger contribution of the local lipid pool as an energetic substrate source during exercise in order to preserve glycogen

[76][78][89,91]. Li, lipid droplet; mc, central mitochondria; mf myofilament; marker indicates 0.5 µm.

Another elementary energy storage substrate in terms of physical exercise is glycogen. There is an inverse relationship of IR-status, glycogen synthase activity and glycogen storage capacity in human skeletal muscle in vivo

[59][79][80][72,92,93]. By contrast, exercise-induced depletion of depots is followed by an enhanced ability to synthesize glycogen

[52][65]. Using a defined depletion-recovery protocol under combined exercise and dietary restriction conditions, followed by carbohydrate overfeeding over days resulted in glycogen storage capacity in humans as high as 15 g per kilogram body weight

[81][94]. Glycogen depletion due to exercise and repletion by dietary intervention during recovery is a routinely used strategy of many athletes

[82][83][95,96]. Moreover, highly trained endurance athletes can increase fatty acid oxidation in response to lipid overload. At the same time glycogen storage within muscle is preserved at the expense of decreasing glucose oxidation. This maneuver, which is associated with higher mitochondrial capacity of the exercised muscle, represents a unique example of metabolic flexibility

[41][54]. As regards NAFLD/MAFLD, improved glycogen storage and mobilization capacity would be desirable, since this would theoretically help to relieve glucose load from the liver and thereby leave less substrate for de novo lipogenesis (reviewed in

[31][44]). Remarkably, a single bout of exercise can substantially rise insulin sensitivity in IR subjects, while the subsequent increase in insulin stimulated skeletal muscle glucose uptake and glycogen synthesis can be observed for up to 48 h. Interestingly, glycogen levels are increased independently from muscle glycogen content under such conditions (reviewed in

[83][96]). Further research is required to explore which preconditions and exercise schedules will result in best clinical results, specifically in ageing human NAFLD/MAFLD patients. However, it appears that exercising in the fasted state can substantially stimulate glycogen synthesis and IMCL breakdown, at least in young healthy volunteers

[84][97]. Moreover, GLUT4 content of skeletal muscle is related to muscle mass, suggesting potential over-additive effects of a combined endurance and resistance exercise schedule

[85][98].

Finally, one aspect in terms of exercise which can potentially result in unfavorable adaptations needs to be discussed. There is a known relationship between exercise intensity and improved glucose uptake

[53][66]. However, very intense exercise (particularly eccentric exercise, i.e., downhill running), resulting in disruption of muscle cell integrity followed by delayed onset of muscle soreness due to eliciting local inflammatory response can decrease glucose disposal in skeletal muscle for up to 48 h (reviewed in

[86][99]). Although earlier data suggest a compensatory pancreatic β-cell response resulting in raised insulin levels after eccentric exercise in young healthy subjects, it is still unclear whether this remains true for older IR patients

[87][100]. Furthermore, it has been shown very recently that excessive training (i.e., high intensity interval training, HIIT) results in impaired mitochondrial function and glucose intolerance

[88][101]. This clearly indicates that exercise schedules for improving insulin action, glucose uptake and ectopic lipid storage in older IR subjects require professional assessment, appropriate planning, monitoring and management.

Together, regular physical exercise can beneficially impact gross adaptational processes involved in fuel storage and mobilization associated with IR. The concept of metabolic flexibility provides some explanation governing fuel selection between NEFA and glucose, with the related substrate shift serving more efficient energy source utilization during exercise. Beyond this metabolic flexibility enables the switch from catabolic to anabolic processes in which energy substrates can be effectively stored after muscle activity

[41][54]. These adaptations are realized by a multitude of modulations on the transcriptomic, proteomic, and epigenomic level. Obviously, AMPK appears to have a key regulatory function in this situation (

[89][90][102,103]; reviewed in

[41][54]). From a pathophysiological perspective the model of metabolic flexibility is specifically attractive under conditions of NAFLD/MAFLD, since it can be concluded from existing literature that the regularly exercised skeletal muscle provides substantial surplus storage capacity for energetic substrates (i.e., NEFA and glucose). Moreover, restoration of skeletal muscle fuel depots relies on provision from food sources, further contributing to relieve the liver from an overflow of potential nutritoxic substrates

[91][92][104,105].