Local governments may seek efficient public service delivery through scaling up production, and the quest for the optimal local government size has attracted extensive attention of scholars and policy makers. Indeed, if scale matters for local government efficiency, increasing size may be a key factor in achieving more value for money for citizens. As such, getting scale right may contribute significantly to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as set out in the 2030 Agenda. Nonetheless, there is considerable uncertainty with regard to how scale shapes the average cost of local government service delivery. These uncertainties may have contributed to policy makers and public organizations disregarding the often inconclusive and sometimes contradictory empirical evidence in stimulating and allowing mergers and consolidation in many Western countries.

This Special Issue is concerned with economies of scale in local government. Interesting issues to be addressed relate to the existence of general and service specific economies of scale and the implications of both for local government policy regarding various types of scaling (amalgamation, cooperation, and outsourcing). Based on a brief literature review, we inventory a number of issues which warrant further research. One of the conclusions is that the relationship between scale and sustainability is a complex issue with many aspects. Examples include the relation between economies of scale and outsourcing and cooperation, issues concerned with multi-level aspects of scale, and the trade-off that may exist between achieving economies of scale and cost efficiency (e.g., transition cost of mergers). Another conclusion is that no such thing as “one size fits all” exists. Different perspectives may play a role and should be born in mind when suggesting solutions and providing recommendations to achieve sustainable goals.

- cost model

- financial sustainability

- environmental sustainability

- economies of scale

- economies of scope

- collaboration

- mergers

- outsourcing

- multi-level

1. Introduction

2. Theory: Economies of Scale and Scope in the Public Sector

- (1)

-

First and foremost, there is the “big stick” approach of merger, in which two or more previously independent organizations are merged into one new, bigger organization. In addition to affecting cost through scale, mergers may also impact short-term and long-term cost efficiency as a result of transition costs. In theory, these effects need not be negative, as mergers may also allow for eliminating inefficiencies, for example by adapting the best governing practice of the merging organizations. Consolidation can also take place between sub-units of organizations. An interesting case emerges when mergers also lead to the provision of a more diversified set of services. In that case, economies of scope may also occur, where economies of scope are defined as the benefits coming from dividing fixed costs over more different services instead of providing more services. This may arise when the merger affects the type of services provided by a local government.

- (2)

-

The second mechanism is cooperation. Two or more organizations can choose to embrace in the joint production of public service delivery. In theory, this allows them to achieve economies of scale in those areas where they may be most prominent, e.g., in capital-intensive or highly standardized services. However, potential downsides include the monitoring cost of governing the cooperation agreements, the cost of aligning processes, and free-rider behavior.

- (3)

-

Third, for the same reasons as under 2), local government may choose to outsource services to larger scale private parties, since they are not able to benefit from scale economies themselves. Examples are public transport, road construction and maintenance, and waste collection. Local governments can collaborate in a joint tender to private parties to enforce their market power to absorb a part of the scale economies of the private party.

- (4)

-

Fourth, organization size may change due to organic growth. While such trends are often insignificant in the short term, they may have significant effects in the long run. Local governments may increase population at the cost of another, or the (average) population may be affected, changing the overall national population.

3. Local Government Scale: A Brief Literature Review

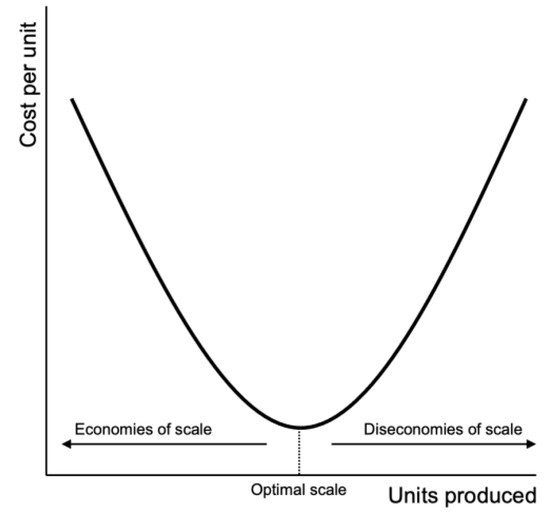

In seeking efficiency gains in the delivery of local public services, many countries have pursued a long-term policy of local government amalgamation. As a result, the number of municipalities in the Netherlands, for example, has steadily decreased from 1015 in 1950 up to 355 in 2019. The policy backgrounds of Dutch local government amalgamation is well-documented [8][9][10]. Economies of scale are considered the main underlying assumption driving local government amalgamation. A more recent trend is that of local governments also seeking economies of scale in specific services through joint production via inter-municipal cooperation. The popularity of inter-municipal cooperation is on the rise in European countries and saving cost is often a key motivation [11].The quest to determine the “optimal” scale of local government jurisdiction has attracted considerable attention of researchers across many disciplines. Essentially, the trade-off between small and big is debated over arguments that favor accessible, approachable local governments and involved citizens on the one hand, versus big, cost-efficient governments on the other hand. Indeed, economies of scale seem to be the dominant argument in favor of increasing local government size [5][12].There is a large literature that empirically analyses economies of scale in local government. Essentially, these studies revolve around regressing measures of cost on measures of (output) size to fit cost functions. Applications started emerging over sixty years ago [13]. A distinction can be made between studies that focus on the overall, local government level and those that focus on the analysis of specific services [14], such as waste collection, road maintenance, or administration. In the analysis at the local government level, by far the most common measure of output size is population count, despite being considered a poor measure over local government output [15]. Service-specific studies have seen far more detailed and accurate output measures used than population count, such as kilograms of waste collected, the length of the road network maintained, or the number of taxes invoiced. Often, economies of scale are reported as a by-product of the more general analysis of local government efficiency (see [16][17] for extensive, recent overviews of the local government efficiency literature), which use so-called frontier techniques such as Stochastic Frontier Analysis (SFA) and Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) to estimate cost functions. Regarding economies of scale and efficiency, Dutch local governments are relatively understudied; although, some studies have emerged recently [18][19][20].By now, several articles have surveyed (parts of) the empirical literature on economies of scale in the provision of local government services [5][15][21][22][23][24]. Foremost, despite its size, the literature is described as inconclusive and in cases, contradictory [22][23][24]. In review of the existing evidence, Blom-Hansen et al. [5] noted that the “the empirical literature on the effects of municipal mergers has failed to identify systematic patterns that hold across time and space”. On the basis of an extensive, international comparison of empirical studies Holzer [23] concluded that municipalities with populations less than 25,000 may still increase efficiency, although, dependent on context, and mostly restricted to specialized, capital-intensive services. Over 250,000 inhabitants, there is more consistent evidence suggesting that diseconomies of scale persist [23]. Local governments provide a heterogeneous set of services and it is indeed recognized that some services are more subject to economies of scale than others. In particular, economies of scale are more likely in capital-intensive services due to the associated fixed cost [5][13][15][23][25][26][27][28][29][30] and in highly specialized, seldomly used services where there is room for labor specialization [5][23]. Surprisingly, mechanisms underlying potential diseconomies of scale in local government services have been discussed to a lesser extent. As mentioned before, diseconomies of scale are typically discussed over bureaucracy concerns [1][25][31]. Diseconomies of scale due to bureaucratic congestion occur when the required inputs for coordination increase disproportionally as output volumes increase. Arguably, high-complexity services may be subject to more pronounced diseconomies of scale, but there is little literature on the moderating factors driving bureaucratic congestion in local government, and thus, why some may be more subject to bureaucratic congestion than others. In summary, the three key mechanisms underlying economies of scale are: (1) fixed cost, (2) specialization, and (3) bureaucratic congestion.A more recent strand of literature exploits within-municipal variation resulting from amalgamation reforms implemented in several countries, including the Netherlands, Denmark, and Israel. These studies allow for a more causal identification of the relation between scale and cost as they observe actual changes that occur after amalgamation, as opposed to the cross-sectional and correlation analysis of economies of scale prevalent in the literature discussed before. The picture arising from these studies is that amalgamation has not led to a systematic decrease in spending in the Netherlands [32] and Denmark [5]; although, evidence for positive merger effects were found in Israel [24]. Regarding Denmark, indeed, cost savings in some services (roads and administration) were offset by cost increases in other areas (labor market services and culture), although most services remained unaffected [5]. Regarding inter-municipal cooperation, a relatively recent phenomenon, researchers are increasingly investigating whether cooperation is an effective reform for reducing cost. Emerging literature on the matter indicates that cooperation can be effective in decreasing cost, but there are some contradictory results (for an extensive and recent overview, see [33]). Recent applications in the Netherlands suggest that inter-municipal cooperation has been effective in decreasing cost in tax collection, but not in other service areas [20][34]. Again, these results highlight the relevance of local government service heterogeneity with regard to economies of scale. In particular, economies of scale through cooperation seems more achievable in capital-intensive services that pose little risk for bureaucratic congestion as output volumes grow. Regarding local governments engaging in outsourcing and privatisation, there is a considerable literature which has indeed suggested economies of scale as one of the key underlying mechanisms [35].4. Research Challenges

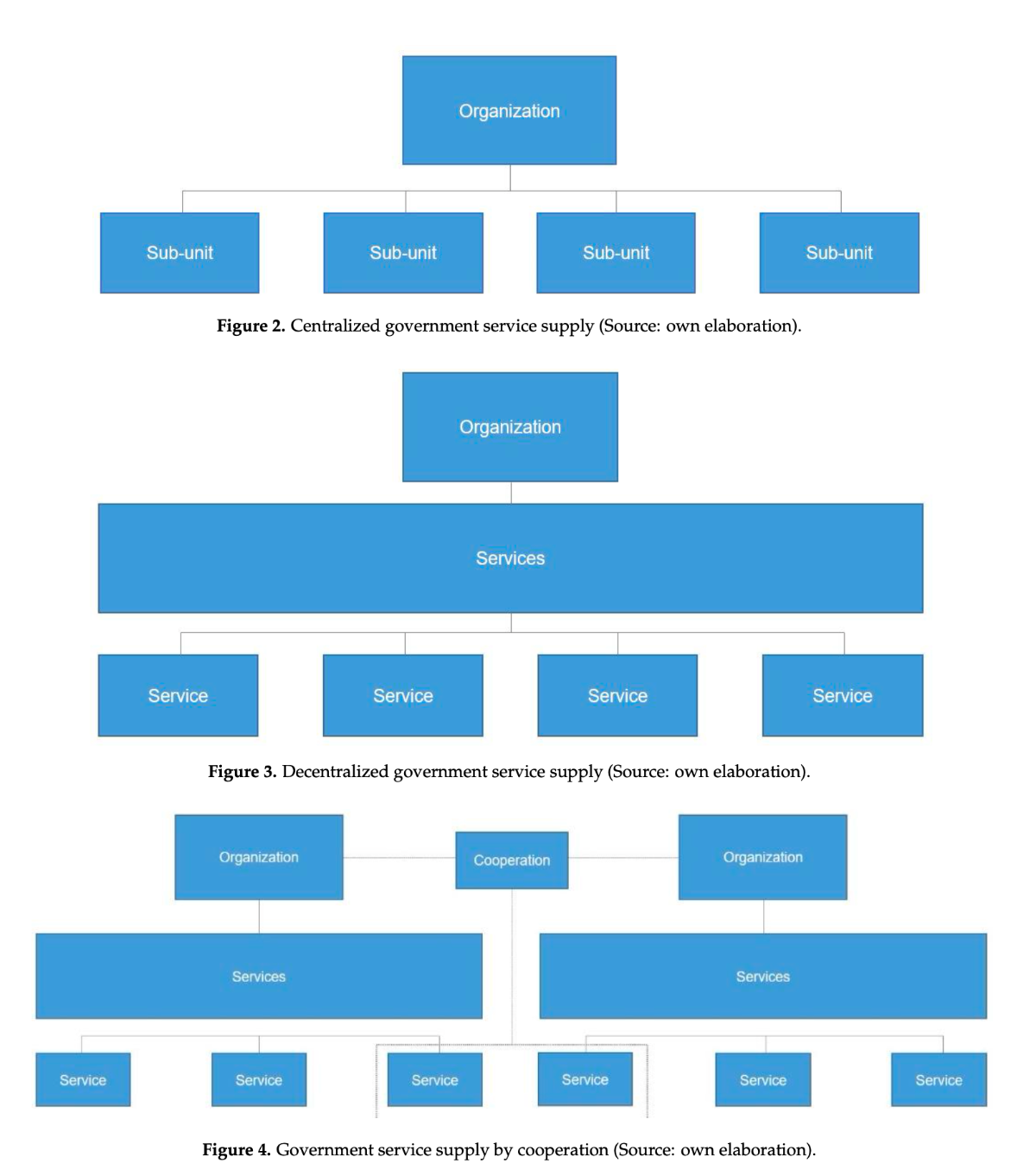

As outlined above, many public organizations are seeking the efficient delivery of public services through scaling up production, and the quest for the “optimal” size of public organizations has attracted extensive attention of scholars and policy makers. Nonetheless, there still is considerable uncertainty surrounding the relation between scale and cost in local government and the determinants that drive this relation. Two important factors that bedevil the analysis of economies of scale are the fact that the output of public organizations is often hard to measure, and the multi-level nature of scale, with no single measure of scale doing justice to the (often complex) nature of public organizations. In studying the relation between scale and cost, researchers commonly measure scale at the firm size, e.g., the administrative unit of a local government. Blom-Hansen et al. [5] explicitly discussed this with relation to local government and distinguish the “firm” (local government) and “plant” size in, e.g., child care centers, libraries, and residential homes for the elderly, and argued that scale effects actually arise mostly at the lower (plant) level of the organization. In order to get an impression about the complexity of the organizational structure of services supply we present a number of diagrams of organizational structures that are common practice on local government services supply.

Figure 2 shows the most elementary form of service supply. Departments within the municipality are responsible for services supply. Examples are, for instance, the provision of official documents (passports and licenses) and the provision of social allowances. Figure 3 represents a form of decentralized service provision. The local government subsidizes private institutions represented by boards, such as school boards Figure 4 represents a form of super-centralized service supply. Services are supplied by a supra-local body, such as the biggest municipality in the cooperation or by a third party contracted by the cooperation.

Aside from the multi-level issue itself—which level are we analyzing—another complex issue arises when different levels are interacting. To illustrate this point we refer to study of Blank et al. [37] that analyzed whether concentrating emergency departments of hospitals is beneficial. They showed that economies of scale at this level indeed exist but are offset by diseconomies of scale at the hospital level resulting from their taking on more patients. Another interesting case regarding different scale levels can be found in the provision and education, which revolves around the distinction between school and school board size. Arguably, economies of scale may arise at both levels. Generally, driven by limitations, existing empirical applications investigate scale effects only with regard to either school, or school board (or district) size. The challenge in both aforementioned studies is to incorporate multiple scale measures in one single model, instead of analyzing at one specific level. These conceptual difficulties may well have contributed to policy makers and public organizations disregarding the often inconclusive and sometimes contradictory empirical evidence in stimulating and allowing mergers and consolidation. The aim of this Special Issue is to narrow this research gap by addressing the relation between economies of scale and consolidation in local government. Some of the relevant research questions are:

-

Are local government services subject to economies of scale, and is there heterogeneity across services?

-

What is the relationship between local government amalgamation, economies of scale and cost?

- What is the relationship between inter-municipal cooperation, economies of scale and cost?

In the context of cooperations, municipalities may import economies of scale, thus benefitting from the larger scale of the cooperation. This implies that the scale at which a municipality produces differs from the scale of output of the cooperation. A proper modelling of this relation contributes to identifying to what extent scale effects can be imported and whether cooperation is associated with transaction costs, i.e., costs that arise due to increased bureaucracy and required alignment. The corresponding research question is:

• To what extent can local governments achieve service-specific economies of scale through inter-municipal cooperation or outsourcing, for instance to private enterprises?

An aforementioned interesting case refers to the distinction between operational and board size. More generally, regarding the multi-level aspect of scale, the most convincing analysis of economies of scale is one that incorporates the size indicators of all relevant operational units in the production process. For example, an analysis of economies of scale in the provision of education by local governments ideally incorporates measures of class size, school size, and the administrative size of the local government. The relevant question here is:

• How can we distinguish between the scale effects of different organizational or administrative levels and integrate them into a framework to assess the efficient size range configuration of each level?

An interesting issue also arises from the cost effects of implementing scale policy measures, in terms for instance in transaction and transition costs. These types of cost may affect cost efficiency for quite some time. Merger may take some time to be fully implemented and may come with substantial extra costs. The analysis should therefore account for these cost efficiency effects as well. The corresponding research question is:

• To what extent do scale policy measures, such as amalgamation and cooperation, affect cost efficiency (other than through scale itself), both in the short- and long-term?

5. Contributions to This Special Issue

Takeshi Miyazaki [38] conducted research on the effects on expenditure of the designation of cities (core or special case cities), thereby giving more freedom to be active in a wider range of services. The author stressed the fact that a larger municipality not only benefits from economies of scale, but also from economies scope or diversification. However, he showed that there is hardly any proof of (dis)economies of scope in public services provided by local governments. In the provision of public services by general local governments, economies of scope could not be established in the short term (2–3 years), but did appear in the mid- to long-term. After the delegation of duties, per capita expenditure for core cities increases by 2.8% immediately after the designation, but then decreases by 0.6% annually.

One of the issues addressed in Section 4 and in a recent study of Niaounakis [8] concerns the large variety in economies of scale between the different municipality functions. An interesting example of substantial economies of scale is presented in this Special Issue by Bernadelli et al. [39]. The authors analyzed economies of scale in municipal administration in the Paraná state local government system in Brazil over the period 2006 to 2018. They found that there is a U-shaped scale effect between council size by population and administrative intensity after controlling for a range of economic and social variables. Economies of scale in municipal administration provide empirical evidence for municipal mergers, since small municipalities expend a larger share on administration than large municipalities. The presence of scale economies in administrative services also favors creating shared services in municipal administration without the need for expensive merger transitions and the abolishment of small municipalities.

In their contribution to the Special Issue, Blank and Niaounakis [40] addressed the issue of economies of scale and the multi-layer aspect of services. One of the main questions for local governments concerns the optimal configuration of administrative layers. In particular, they focused on the optimal size of school boards and optimal size of schools. They analyzed the relation between cost and scale in school boards and in schools simultaneously. The influence of both the governing layer (board) and the operational layer (school) on average cost are jointly modelled. They applied their model to Dutch primary schools. The results indicate that small schools (<60) pupils are operating under sizable economies of scale. The optimum school size is estimated at roughly 450 pupils, but average cost remains roughly constant with regard to size. In contrast to school size, the effect of board size (in terms of the number of schools governed) on average cost is limited. The policy recommendation is that municipalities should create schoolboards with at least three schools within their jurisdiction and take measures in case individual school size declines below 60 pupils.

Blank [41] presented an analysis of the efficiency and productivity of the provision of school buildings by Dutch municipalities. A cost function is estimated for the years 2005–2016 using stochastic frontier methods based on data of Dutch municipalities. In his contribution Blank made an explicit connection between financial and environmental sustainability. Building operations and construction are responsible for a large part of global energy use and carbon dioxide emissions. This implies that more efficient provision of school buildings may serve financial as well as climate goals. The results indicate that inefficiency and non-productiveness are substantial among Dutch municipalities. Provision of school buildings on a more appropriate scale (mostly larger scale), detailed performance benchmarking, and including more incentives for innovative behavior may result in a more sustainable provision of school buildings and less energy use and emission of carbon dioxide.

6. Discussion

Although there is an extensive literature on economies of scale in local government, the literature has been described as inconclusive. As such, it has proven hard to provide policy makers and public managers with consistent recommendations regarding the efficient size of public service delivery in local government. This Special Issue aims to contribute to the literature on local government economies of scale and pays particular attention to the conceptual complexity regarding scale. The focus of this Special Issue is strongly directed towards financial sustainability, but in many cases, this goes hand in hand with environmental sustainability, as was pointed out in one of the contributions. Many of the services produced by local government are directly related to infrastructural works, such as school buildings, public libraries, roads, public transportation, and so on. Efficiency improvement in these services may also lead to lower energy consumption and emissions of carbon dioxide. It must therefore be stressed that in many cases efficiency and sustainability do not conflict. In case they do, efficiency and sustainability can easily be aligned by merely including sustainable outcomes, such as low emissions, into the efficiency framework.

References

In a number of contributions, the Special Issue recognized that economies of scale vary between the heterogeneous services local governments provide (multi-service) and between different vertical hierarchical levels within local governments (multi-level). Aside from the number of services produced per type of services another issue related to scale has a relevant impact. Differences in size may also imply a difference in function of the municipality. Cities have a strong appeal on people and business coming from outside the municipality and may therefore affect the types of services delivered. In these cases, the scope of services provided correlates with scale. This, in turn, may have important methodological implications for the analysis of economies of scale and the implications drawn for the optimal scale policy of local governments.

Instead of searching for the holy grail of an optimal organizational scale we would like to raise the awareness amongst researchers, policy makers, and politicians about the complexity of the scale issue in the context of local government performance. There is obviously no such thing as one size fits all. Different perspectives may play a role and should be borne in mind when suggesting solutions and providing recommendations to achieve sustainable goals. Although some of the questions raised will be foreseen with clear cut answers in this Special Issue, others, however, will still be unresolved and requires further research. The research agenda may follow the different perspectives aligned with the conceptual framework presented in this paper and fill in the knowledge gaps accordingly.

Author Contributions: Both authors have contributed equally to the work reported. Writing— original draft preparation, J.L.T.B., T.K.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding: This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.References

[1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12][13][14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29][30][31][32][33][34][35][36][37][38][39][40][41]

References

- United Nations. The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2020, New York. 2021. Available online. (accessed on 26 November 2021).

- Blank, J.L.T. Illusies over Fusies. Een kritische Beschouwing over de Schaalvergroting in de Nederlandse Publieke Sector; CAOP: Den Haag, The Netherlands, 2015; Volume 41.

- Williamson, O.E. Hierarchical Control and Optimum Firm Size. J. Polit. Econ. 1967, 75, 123–138. [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, E.F. Small Is Beautiful: A Study of Economics As If People Mattered; Sphere Books: London, UK, 1970. Available online. (accessed on 26 November 2021).

- Stigler, G.J. The economies of scale. J. Law Econ. 1958, 1, 54–71. [CrossRef]

- Blom-Hansen, J.; Houlberg, K.; Serritzlew, S.; Treisman, D. Jurisdiction Size and Local Government Policy Expenditure: Assessing the Effect of Municipal Amalgamation. Am. Politi.-SCi. Rev. 2016, 110, 812-831. [CrossRef]

- Boyne, G. Population Size and Economies of Scale in Local Government. Policy Polit. 1995, 23, 213–222. [CrossRef]

- Niaounakis, T.K. Economies of Scale: A Multi-Level Perspective Applications in Dutch Local Public Services; Delft University of Technology: Delft, The Netherlands, 2021.

- Portengen, R. Beleidsdynamiek en Schaalpolitiek. Opkomst van de Menselijke Maat in Schaalbeleid? Erasmus University Rotterdam: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2018.

- Voermans, W.; Waling, G. Gemeente in de Genen. Tradities en Toekomst van de Lokale Democratie in Nederland; Prometheus: Amsterdam, The netherlands, 2018.

- Allers, M.A. Decentralisatie en gemeentelijke opschaling. Lib. Reveil 2013, 52, 119–124.

- Bel, G.; Warner, M. Inter-municipal cooperation and costs: Expectations and evidence. Public Adm. 2015, 93, 52–67. [CrossRef]

- Fox, W.F.; Gurley-Calvez, T. Will Consolidation Improve Sub-National Governments? The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2006; p. 3913

- Hirsch, W.Z. Expenditure Implications of Metropolitan Growth and Consolidation. Rev. Econ. Stat. 1959, 41, 232. [CrossRef]

- De Borger, B.; Kerstens, K. Cost efficiency of Belgian local governments: A comparative analysis of FDH, DEA and econometric approaches. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 1996, 16, 145–170. [CrossRef]

- Turley, G.; Mcdonagh, J.; McNena, S.; Grzedzinski, A. Optimum Territorial Reforms in Local Government: An Empirical Analysis of Scale Economies in Ireland. Econ. Soc. Rev. 2018, 49, 463–488.

- Narbón-Perpiña, I.; de Witte, K. Local governments’ efficiency: A systematic literature review-part I. Int. Trans. Oper. Res. 2018, 25, 431–468. [CrossRef]

- Narbón-Perpiña, I.; de Witte, K. Local governments’ efficiency: A systematic literature review-part II. Int. Trans. Oper. Res. 2018, 25, 1107–1136. [CrossRef]

- Bikker, J.; van der Linde, D. Scale economies in local public administration. Local Gov. Stud. 2016, 42, 441–463. [CrossRef]

- Blank, J.L. Measuring the performance of local administrative public services. BRQ Bus. Res. Q. 2018, 21, 251–261. [CrossRef]

- Niaounakis, T.; Blank, J. Inter-municipal cooperation, economies of scale and cost efficiency: An application of stochastic frontier analysis to Dutch municipal tax departments. Local Gov. Stud. 2017, 43, 533-554 [CrossRef]

- Bish, R.L. Local government amalgamations: Discredited nineteenth century ideals alive in the twenty first. Comment. Howe Inst. 2001, 150, 1.

- Byrnes, J.; Dollery, B. Do Economies of Scale Exist in Australian Local Government? A Review of the Research Evidence1. Urban Policy Res. 2002, 20, 391-414 [CrossRef]

- Holzer, M.; Fry, J.; Charbonneau, E.; van Ryzin, G.; Wang, T.; Burnash, E. Literature Review and Analysis Related to Optimal Municipal Size and Efficiency; Rutgers University: Newark, NJ, USA, 2009.

- Reingewertz, Y. Do municipal amalgamations work? Evidence from municipalities in Israel. J. Urban Econ. 2012, 72, 240–251.[CrossRef]

- Drew, J.; Kortt, M.A.; Dollery, B. Did the Big Stick Work? An Empirical Assessment of Scale Economies and the Queensland Forced Amalgamation Program. Local Gov. Stud. 2014, 42, 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Dollery, B.; Fleming, E. A Conceptual Note on Scale Economies, Size Economies and Scope Economies in Australian Local Government. Urban Policy Res. 2006, 24, 271-282.[CrossRef]

- Bel, G.; Mur, M. Intermunicipal cooperation, privatization and waste management costs: Evidence from rural municipalities. Waste Manag. 2009, 29, 2772–2778. [CrossRef]

- Bel, G. Local government size and efficiency in capital-intensive services: What evidence is there of economies of scale, densityand scope? In The Challenge of Local Government Size Theoretical Perspectives, International Experience and Policy Reform; EdwardElgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2013; pp. 148–170.

- Andrews, R. Local government size and efficiency in labor-intensive public services: Evidence from local educational authorities in England. In The Challenge of Local Government Size Theoretical Perspectives, International Experience and Policy Reform; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2013; pp. 171–188.

- Foged, S.K. The Relationship Between Population Size and Contracting Out Public Services: Evidence from a Quasi-experiment in Danish Municipalities. Urban Aff. Rev. 2014, 52, 348–390. [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, C.; Saving, T. Long-Run Scale Adjustments of a Perfectly Competitive Firm and Industry. Am. Econ. Rev. 1969, 59, 774–783.

- Allers, M.A.; Geertsema, J.B. The effects of local government amalgamation on public spending, taxation, and service levels: Evidence from 15 years of municipal consolidation. J. Reg. Sci. 2016, 56, 659–682. [CrossRef]

- Bel, G.; Warner, M. Factors explaining inter-municipal cooperation in service delivery: A meta-regression analysis. J. Econ. Policy Reform 2015, 19, 91–115. [CrossRef]

- Allers, M.A.; De Greef, J. Intermunicipal cooperation, public spending and service levels. Local Gov. Stud. 2016, 44, 127–150. [CrossRef]

- Bel, G.; Fageda, X. What have we learned from the last three decades of empirical studies on factors driving local privatisation? Local Gov. Stud. 2017, 43, 503–511. [CrossRef]

- Blank, J.L.T.; Van Hulst, B.L.; Valdmanis, V.G. Concentrating Emergency Rooms: Penny-Wise and Pound-Foolish? An Empirical Research on Scale Economies and Chain Economies in Emergency Rooms in Dutch Hospitals. Health Econ. 2016, 26, 1353–1365.[CrossRef]

- Miyazaki, T. Economies of Scope and Local Government Expenditure: Evidence from Creation of Specially Authorized Cities in Japan. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2684.[CrossRef]

- Bernardelli, L.V.; Dollery, B.E.; Kortt, M.A. An Empirical Analysis of Scale Economies in Administrative Intensity in the Paraná State Local Government System in Brazil. Sustainability 2021, 13, 591.[CrossRef]

- Blank, J.L.T.; Niaounakis, T.K. Managing Size of Public Schools and School Boards: A Multi-Level Cost Approach; Dutch Primary Education. 2019. Available online. (accessed on 26 November 2021).

- Blank, J.L.T. Sustainable Provision of School Buildings in The Netherlands: An Empirical Productivity Analysis of LocalGovernment School Building Operations. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9138. [CrossRef]