The pattern recognition receptors, complement system, inflammasomes, antimicrobial peptides, and cytokines are innate immunity soluble factors. They sense, either directly or indirectly, the potential threats and produce inflammation and cellular death. High interest in their modulation has emerged lately, acknowledging they are involved in many cutaneous inflammatory, infectious, and neoplastic disorders. We extensively reviewed the implication of soluble factors in skin innate immunity. Furthermore, we showed which molecules target these factors, how these molecules work and how they've been used in dermatological practice. Cytokine inhibitors have paved the way to a new era in treating moderate to severe psoriasis and atopic dermatitis.

- innate immunity

- pattern recognition receptors

- cytokines

- inflammasomes

- complement

- antimicrobial peptides

- imiquimod

- biologics

1. Introduction

2. Pattern Recognition Receptors

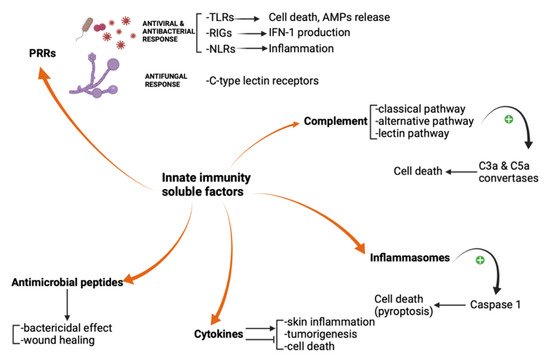

Fungi, protozoa, viruses, and bacteria share common pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), which are identified by the innate immune system via highly specialized receptors, the so-called “pattern recognition receptors” (PRRs). These receptors are exposed both on immune and non-immune cells and serve as a first-line defense against PAMPs. Four major families of pattern recognition receptors have been described yet: Toll-like receptors (TLRs), RIG-I-like receptors (RIGs), NOD-like receptors (NLRs), and the C-type lectin receptors. The innate immune system uses PRRs to distinguish between self entities and microorganisms. Autoimmune diseases may be linked to PRRs recognition of self molecules, such as nucleic acids [4][5][6]. For example, the aberrant activation of the innate immune response in cutaneous lupus erythematosus is triggered by the cellular debris, rich in endogenous immunostimulatory nucleic acids which bind to PRRs and induce interferon responses and inflammasome activation [7]. TLRs are a family of glycoproteins usually expressed by granulocytes, dendritic cells, macrophages, and monocytes. Keratinocytes may express TLRs as well. TLRs are located on the cell surface, in the cellular plasma membrane, and in intracellular compartments. They contain ectodomains that mediate PAMPs recognition and transmembrane domains and endo-domains necessary for downstream signal transduction [6]. Apoptosis, shaping the development of the adaptive immune response, and triggering the release of antimicrobial peptides are important TLRs activation consequences [8]. While TLRs recognize endosomal nucleic acids, the retinoic acid-inducible gene (RIG)-I-like receptors (RIGs) detect cytosolic viral RNA and induce type I interferon production. Twenty-two intracellular NOD-like receptors (NLRs) classify into four subfamilies based on their N-terminal domain. NOD1 and NOD2 receptors recognize peptidoglycans from the bacterial wall and finally promote pro-inflammatory mediators’ expression, while NLRP3 activation leads to inflammasome assembly. C-type lectin receptors are glycosylated type-II transmembrane PRRs that promote anti-fungal effects via their carbohydrate-recognition domains (CRDs). Representative members of this family include dendritic cell-associated C-type lectin 1 (Dectin 1), Dectin 2, macrophage C-type lectin (MCL), and macrophage inducible C-type lectin (Mincle). Mincle is capable to respond to C. albicans and Malassezia species (Figure 1) [5][6][7].

3. Complement

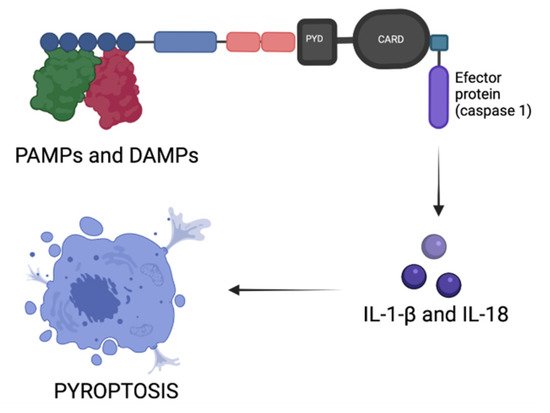

4. Inflammasomes

5. Antimicrobial Peptides

Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) are an evolutionarily preserved family of peptides found both in vertebrates and invertebrates that consist of 20–60 amino acids in length [20]. AMPs display the capacity to announce infection or injury; therefore, the term “alarmins” is common for some AMPs. AMPs were initially described in the wound repair process, and further research has proved their bactericidal effect and capacity to alert the host and activate the immune system [21]. This bactericidal mechanism is due to the cationic structure of most of the AMPs that attach to the anionic bacterial cell surface, as described for group A Streptococcus and other bacteria [22]. Defensins, cathelicidins, dermcidins, and other molecules, such as RNase 7, psoriasin, and lactoferrin, are among AMPs produced in human skin [20]. Although more than 20 different proteins were proven to provide antimicrobial activity, cathelicidins and β-defensins are the most precisely described AMPs [23]. Both cathelicidins and β-defensins are negligible in normal skin. Per contra, an increased expression in the superficial epidermis was shown in psoriasis. A lower expression was found in eczematous lesions from atopic dermatitis patients, which may be significant in terms of their susceptibility to developing skin infections with gram-positive germs [24]. AMPs have demonstrated an important role in wound healing and re-epithelization, by increasing angiogenesis, cell proliferation, and preventing pathogen multiplication in the injured tegument [25]. Furthermore, cathelicidins inhibition was linked with impaired re-epithelialization in wounded organ-cultured human skin [26].6. Cytokines

Cytokines represent a family of small proteins (<40 kDa) released by most of the cells, mainly macrophages and helper T cells, that display a specific effect on the immune response. They can act on distant cells, nearby cells (a paracrine mechanism), or the same cells that secrete them (an autocrine mechanism) [[27], [28]]. Both pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines are secreted during the immune response, however, their effects depend on the targeted cells [[29][30][31]].

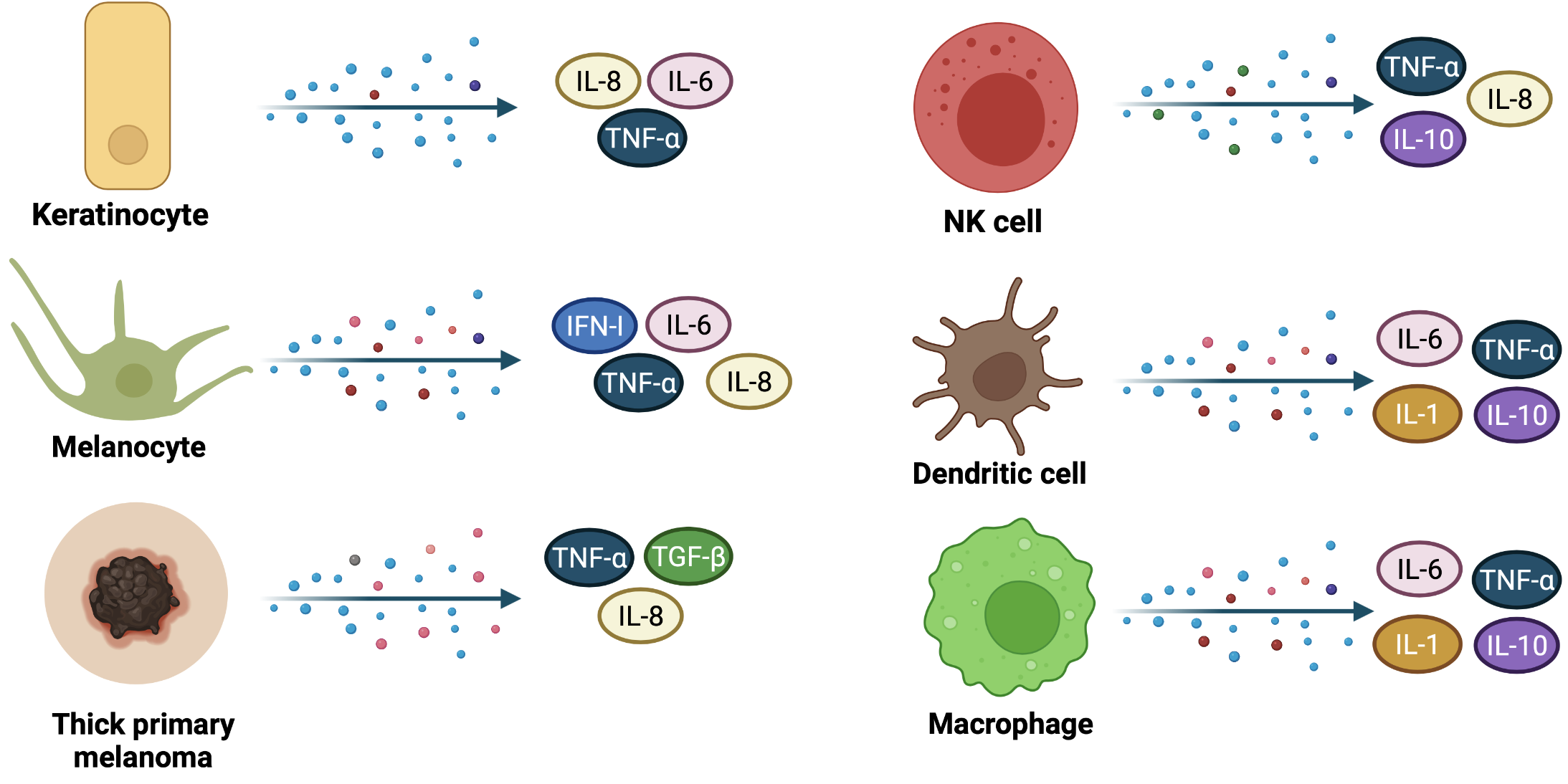

Keratinocytes also produce many cytokines, such as interleukin-1 (IL-1), interleukin-6 (IL-6), interleukin-7 (IL-7), interleukin-8 (IL-8), interleukin-10 (IL-10), interleukin-12 (IL-12), interleukin-15 (IL-15), interleukin-18 (IL-18), interleukin-20 (IL-20), and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) [[32]]. It was proved that various environmental molecules such as sodium lauryl sulfate, phenol, and croton oil induce IL-8 and other proinflammatory cytokines expression, production, and release in human keratinocyte cultures, suggesting their importance in skin inflammation [[33]]. HPV infection, especially high-risk strains, was linked with increased expression of IL-6 in infected keratinocytes promoting local tumorigenesis [[34]].

Melanocytes are neuroimmune cells that express type I IFN as an early innate response to viruses. They respond against pathogens using PRRs and can initiate cell death accompanied by IFN-b, TNF-a, IL-6, and IL-8 expression, as a response to some viral analogs [[35]]. Nevi and thin primary melanomas show little expression of TNF-α, transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), and IL-8, while a marked-up regulation of cytokines and growth factors can be noticed in thick primary melanomas and metastatic melanomas [[36]]. The melanoma inhibitor of apoptosis protein (ML-IAP) is an important regulator of apoptosis that inhibits caspase activation and TNF signaling, frequently overexpressed in melanoma cells, but with low expression in normal melanocytes. Expression of ML-IAP has been proved to enhance apoptosis resistance in melanoma by binding caspases 3, 7 and 9, and to provide melanoma cells a higher endurance during tumor progression [[37]]. Although melanoma cells possess this apoptosis-escape mechanism, the roles of non-apoptotic cell death signaling pathways, such as autophagy-dependent cell death, necroptosis (caspase-independent cell death, similar to necrosis), ferroptosis (iron-dependent lipid-peroxides induced cell death), pyroptosis (via inflammasomes), and parthanatos (mitochondrial accumulation of poly(ADP-ribosyl)ated proteins’ induced cell death) are of major importance as well [[38]].

Many cytokines produced by other resident skin cells such as macrophages, NK cells, dendritic cells (Figure 4), or endothelial cells, act at numerous levels to control the cornification process, intercellular adhesion, or the expression of some genes that encode important enzymes. Skin barrier regulation is dictated by the interaction between ligands (cytokines) and cytokine receptor complexes, activating several signaling pathways such as Janus kinase/ Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription (JAK/ STAT), Phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K/AKT), Mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) and Nuclear Factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NFκB) [[31],[39]].

Figure 4. Cytokines release during skin immune response and in thick primary melanomas. Keratinocytes, melanocytes, and other innate immunity cells, such as NK cells, dendritic cells and macrophages secrete cytokines that may serve both as pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory molecules or may trigger carcinogenesis (IL-6). Thick primary melanomas secrete IL-8, TNF-α, and TGF-β, suggesting a high synthesis rate within neoplastic cells.

7. How does Imiquimod target PRRs?

In addition to their role in preventing infection, TLRs possess both tumorigenic and anti-neoplasia effects. TLRs expressed on the cancerous cells’ membrane promote invasion and metastasis in some cancers, while they inhibit neoplasia progression in others [[40]].

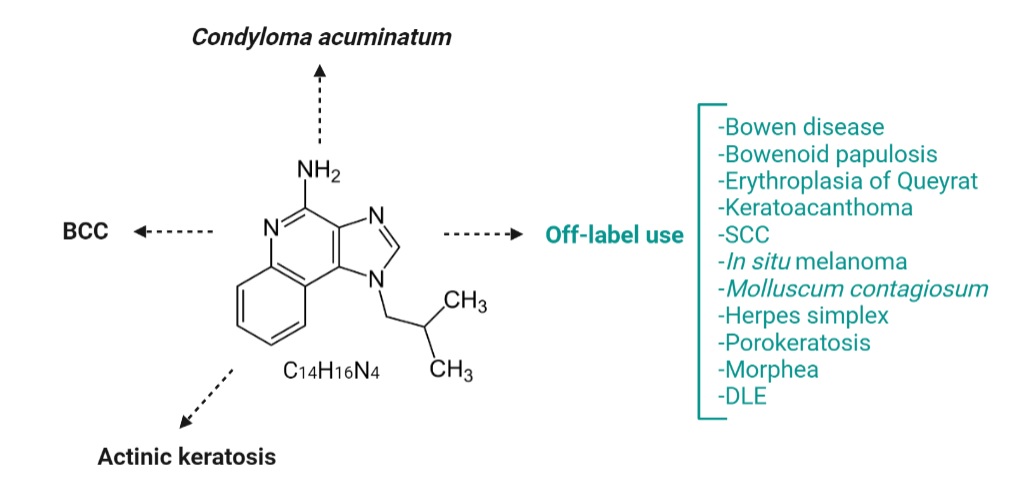

Initially known as S-26308 or R-837, Imiquimod (1-(2-methyl propyl)-1H-imidazo-[4,5-c]-quinoline-4 amine) is an imidazoquinoline amine analog to guanosine (Figure 5), approved for the treatment of actinic keratosis (AK), superficial basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and anogenital warts (condyloma acuminatum), but is widely used in some other skin disorders as well. Imiquimod binds to the TLR-7 localized on the surface of Langerhans cells, dendritic cells, and monocytes and induces TNF-α and IFN-α secretion, proving its antiviral and antitumor effect [[41]]. Huang et al. previously showed that Imiquimod could induce immunogenic cell death (ICD) in vivo and in vitro. Imiquimod-induced ICD consists of reactive oxygen species (ROS) production in cancer cells. ROS trigger endoplasmic reticulum stress and subsequently promotes surface exposure of calreticulin, ATP dependent autophagy, and postapoptotic release of high mobility group box-1 protein (HMGB1). HMGB1 eventually promotes maturation of antigen-presenting cells and tumor antigen presentation [[42]].

Figure 5. Imiquimod chemical structure (central) and approved and off-label use of Imiquimod in skin diseases. Imiquimod is an amine analog to guanosine, currently approved for topical treatment of BCC, KA, and anogenital warts. Nowadays, in dermatological practice, imiquimod is an off-label drug used to treat many skin diseases, such as inflammatory skin disorders, neoplastic diseases, or skin infections. SCC=squamous cell carcinoma; DLE=discoid lupus erythematosus.

7.1. Imiquimod in basal cell carcinoma (BCC)

A 2019 meta-analysis on 4256 patients compared the safety and efficacy of imiquimod with other treatments in patients with BCC (including vehicle, excisional surgery, cryosurgery, 5-fluorouracil, methylamino levulinate photodynamic therapy). Imiquimod associated significant higher histological clearance rate (RR = 9.28, 95% CI: 5.56, 15.49; p < 0.001) and complete response rate (RR=3.15, 95% CI: 1.55, 6.38; p=0.001). Imiquimod was slightly inferior when comparing the success rates (RR=0.93, 95%CI: 0.90, 0.96; p < 0.001). The authors suggest that imiquimod should be used as the first choice of treatment for BCC [[43]]. A multicentre, non-inferiority randomized controlled trial (RCT) with 501 participants with nodular and superficial basal cell carcinoma who were divided in two groups (imiquimod group, 254 participants and surgical excision group, with 247 participants) concluded that there is no obvious difference between groups regarding the cosmetic outcome, but treatment successfulness for imiquimod was inferior to surgery (88% in imiquimod group, comparative to 98% in surgery group) [[44]]. According to the European consensus published in 2019, Imiquimod is particularly useful in low-risk single or multiple superficial BCC, with limited evidence on nodular BCC, but with a better response comparative to methyl-aminolevulinate photodynamic therapy for superficial BCC [[45]].

7.2. Imiquimod in actinic keratosis

Ogawa et al. have used an antibody specific to plasmacytoid dendritic cells to investigate whether imiquimod stimulates these cells’ recruitment to AK lesions. Histological staining demonstrated that plasmacytoid dendritic cells were significantly more abundant after the topical treatment and their number inversely correlated with healing duration, indicating that these cells are critically involved in the regression of AK during imiquimod treatment [[46]].

In a randomized trial, imiquimod cream 5% effectiveness in AK was compared with other three topical treatments (ingenol mebutate gel 0,015%, fluorouracil cream 5%, methyl aminolevulinate photodynamic therapy). The study concluded that 5% fluorouracil was significantly more effective than imiquimod, MAL-PDT, or ingenol mebutate at 12 months for multiple AKs [[47]]. In a meta-analysis of five randomized double-blinded trials treating 1293 patients with AK (with almost 90% men) complete clearance occurred in 50% of patients treated with imiquimod and most adverse events were local, most frequently erythema, scabbing, and flaking, but serious adverse events were not significantly different between imiquimod or vehicle control, with a relative risk of 1.2 (0.7–2.0) [[48]].

An article from 2015 suggested that imiquimod cream 3,75% is the only effective treatment across a large sun-exposed field (full face or balding scalp), for both clinical and subclinical AK (unmasked by imiquimod during treatment). The median percentage decline in lesions was 92%, and the efficient clearance of both clinical and subclinical lesions led to unremitting lesion clearance for at least 12 months. The authors concluded that imiquimod can reveal patients’ entire burden of disease and SCC risk [[49]].

7.3. Imiquimod in condyloma acuminatum

A 2020 meta-analysis included all the RCTs that evaluated topical treatments for external genital warts and revealed podophyllotoxin 0,5% solution is significantly more effective compared to imiquimod 5% cream. However, it was associated with a higher overall adverse event rate. None of the above treatments were significantly different from each other in terms of relapse. [[50]].

In genital (penile) warts, imiquimod clearance rates are similar to those of podophyllotoxin, if applied three times per week until total clearance or for a maximum of 16 weeks for imiquimod cream 5%, respectively every night for up to 8 weeks for imiquimod cream 3,75%. The treatment surface should be washed six to ten hours after application to minimize local adverse events [[51]]. In a RCT comprising 228 patients, an eight-week combination therapy of 400mg oral zinc sulfate with topical imiquimod for vulvar warts significantly decreased relapse after six months [[52]].

7.4. Imiquimod off-label use

Off-label use of imiquimod is not rare in our daily practice. Imiquimod possesses an immunomodulatory effect in neoplastic, infectious, and inflammatory skin disorders [[53]].

7.4.1. Bowen disease

Several clinical studies and case reports investigated imiquimod efficiency in Bowen disease. A retrospective study of 49 patients (96% males, 96% Caucasians, various body locations) concluded that 86% had a complete clinical response with topical imiquimod [[54]]. In an open-label study sixteen patients with a single biopsy-proven lesion that was 1 cm or larger in diameter (up to 5,4 cm) assigned to once-daily self-application of imiquimod 5% cream for 16 weeks. Histological clearance was obtained in their 6-week posttreatment biopsy specimens in 93% of the lesions [[55]]. However, more extensive studies are necessary to compare imiquimod with other nonsurgical therapies in Bowen disease.

7.4.2. Bowenoid papulosis

Resembling condyloma acuminatum, but with the histopathological appearance of Bowen’s disease, Bowenoid papulosis of the genital area can display a good response to topical imiquimod 5% [[56]], but the results are scarce, in few case reports. An almost complete regression to topical imiquimod in monotherapy was obtained in HIV patients [[57]]. Favorable results are obtained in Bowenoid papulosis patients who are HIV positive, when combining oral acitretin with topical 5% imiquimod [[58]].

7.4.3. Erythroplasia of Queyrat

With the cost of moderate burning sensation, imiquimod 5% can be an alternative for surgical and invasive procedures, which may provide poor cosmetic and functional outcomes since this type of in situ carcinoma is usually located on the glans of the penis [[59]]. In negative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testings for HPV, imiquimod efficiency is most likely explained by cytokines’ activation, with antitumor effect, as shown in BCC [[60]].

7.4.4. Keratoacanthoma (KA)

Complete surgical excision is the treatment of choice, but poor cosmetic outcomes may arise. Thus, conservative treatments using podophyllin, 5-fluorouracil, imiquimod, or even intralesional injection of methotrexate or corticosteroids may be beneficial. Topical imiquimod 5% was successfully used in some solitary facial KA [[61]], and low-dose acitretin association was documented to promote complete resolution in multiple KAs patients [[62]]. Contrariwise, a retrospective study showed that conservative treatments led to significantly higher recurrence rates when compared to surgical treatment [[63]].

7.4.5. Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC)

The available studies do not currently endorse topical treatments in SCC; therefore, surgical excision is the preferred treatment [[64]]. When applied over large surfaces, inflammation may occur, decreasing topical imiquimod usefulness in field cancerization. 5-fluorouracil is preferred instead [[65]].

7.4.6. In situ melanoma

Topical imiquimod 5% can be used as a second-line treatment in lentigo maligna, particularly in large tumors, which are located on the face, ears, or scalp, especially in poor surgical candidates and old patients. Adjuvant imiquimod after complete surgical excision showed improved outcomes in terms of local recurrence [[66]]. Other skin malignancies that may respond to topical imiquimod include extramammary Paget disease (alternative treatment to surgery) [[67]], the classical form of Kaposi disease (safe and suitable for home application) [[68]], folliculotropic mycosis fungoides [[69]], or melanoma skin metastases (palliative therapy, favors metastases resolution) [[70]].

7.4.7. Molluscum contagiosum

On the one hand, a recent case-control study on 48 pediatric patients recommends topical imiquimod as a first-line treatment in children with disseminated lesions [[71]]. On the other hand, some scientists found the use of imiquimod in children with molluscum contagiosum not only inefficient but also hazardous, considering high systemic absorption, hematological abnormalities [[72]], and even pemphigus-like eruption as side-effects [[73]].

7.4.8. Herpes simplex virus (HSV)

7.4.8. Herpes simplex virus (HSV)

Acyclovir is a drug extensively used to treat HSV infections. Some recent studies have even investigated vaginal acyclovir delivery methods [[74]]. In few case reports, immunocompromised patients with acyclovir-resistant anogenital herpes simplex were reported to respond to topical administration of imiquimod, thus avoiding the intravenous administration of toxic antiviral drugs, such as cidofovir or foscarnet [[75]]. Imiquimod interacts with the adenosine receptor A1, activating the protein kinase A pathway and upregulating cystatin A synthesis in infected nonimmune cells, proving an IFN-independent antiviral mechanism [[76]]. Herpes simplex virus (HSV) can manipulate TLR and evade the innate immune response. Recent studies showed that HSV‐mediated TLR signaling enables virus replication and suppresses interferon production via NF‐κB signaling [[77]]. Another double-stranded DNA virus, varicella-zoster virus, can induce proinflammatory cytokines upon activation of TLR-2, while TLR-2 abnormalities were associated with an increased number of local recurrences in patients with genital HSV infection [[78]].

7.4.9. Porokeratosis

Several case reports proved that porokeratosis of Mibelli has a favorable response to topical imiquimod 5%, both in children and elders, including some severe cases, nonresponsive to prior cryotherapy or 5-fluorouracil [[79],[80]]. It is also beneficial in some patients with disseminated or linear porokeratosis. Some authors suggest that imiquimod may modulate p53 tumor suppression protein and have reported overexpressed or mutant p53 protein in porokeratosis lesions; therefore, a p53-dependent mechanism may explain imiquimod efficiency in porokeratosis [[81],[82]].

7.4.10. Morphea

Imiquimod's effectiveness in morphea is attributed to its capacity to induce local interferon synthesis, which inhibits collagen production by human fibroblasts, as shown in other sclerodermoid disorders. A prospective, open-label, double-baseline study from 2011 showed that topical imiquimod 5% is effective and safe in children with plaque morphea. A decrease in the thickness of the plaques was quantified using ultrasound [[83]]. Contrarily, a 2015 study that enrolled 25 adult patients with plaque morphea showed no ultrasonographic differences in thicknesses between the treatment and vehicle groups, but induration demonstrated a favorable response [[84]].

7.4.11. Discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE)

Following imiquimod 5% treatment, patients with generalized DLE showed remission, after 20, respectively 24 applications, in two case reports [[85], [86]]. Nevertheless, imiquimod-induced cutaneous lupus erythematosus has been reported in the literature [[87]].

8. Targeting other soluble factors

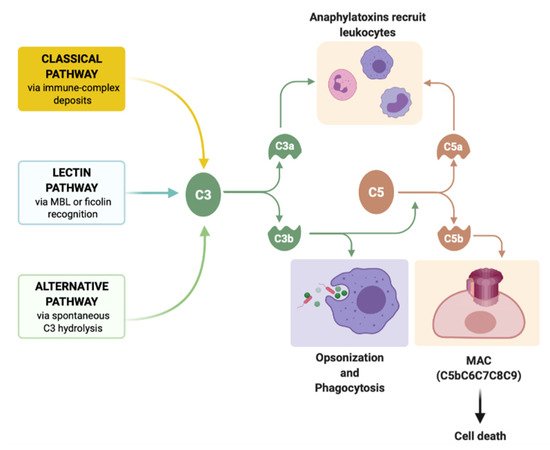

Complement pathways are associated with several skin disorders, such as bullous pemphigoid, psoriasis, urticaria, urticarial vasculitis, hidradenitis suppurativa, vasculitis, and lupus erythematosus. Consequently, the interest in producing complement-specific molecules has been increasing [[88]]. Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) binds C1q, C3, and C4, preventing C1 attack and C3 and C4 in situ deposition, respectively. IVIG also downregulates C3 convertase activity, therefore it is successfully used in some small-medium-vessel vasculitides [[89]]. Eculizumab and its long-lasting form, ravulizumab, are monoclonal antibodies that bind to C5 and inhibit its cleavage by C5a, both approved for paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria [[90]]. IFX-1, an anti-C5a inhibitor, was evaluated in a trial involving 12 participants with hidradenitis suppurativa (NCT03001622); however, no results are currently available [[91]].

Canakinumab is an interleukin-1 monoclonal human antibody that can successfully control and prevent flares in patients with colchicine-resistant familial Mediterranean fever, mevalonate kinase deficiency, and tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated periodic syndrome, as proved in a 2018 study [[92]]. Canakinumab is additionally effective in Schnitzler syndrome, with the cost of infection as a frequently encountered adverse event [[93]], and can also represent a therapeutic option for steroid-resistant pyoderma gangrenosum [[94]]. Some cases of pyoderma gangrenosum remain refractory to this treatment [[95]]. Anakinra is an IL-1 inhibitor that demonstrated a decreased disease activity of moderate to severe hidradenitis suppurativa in a five-patient open-label study [[96]].

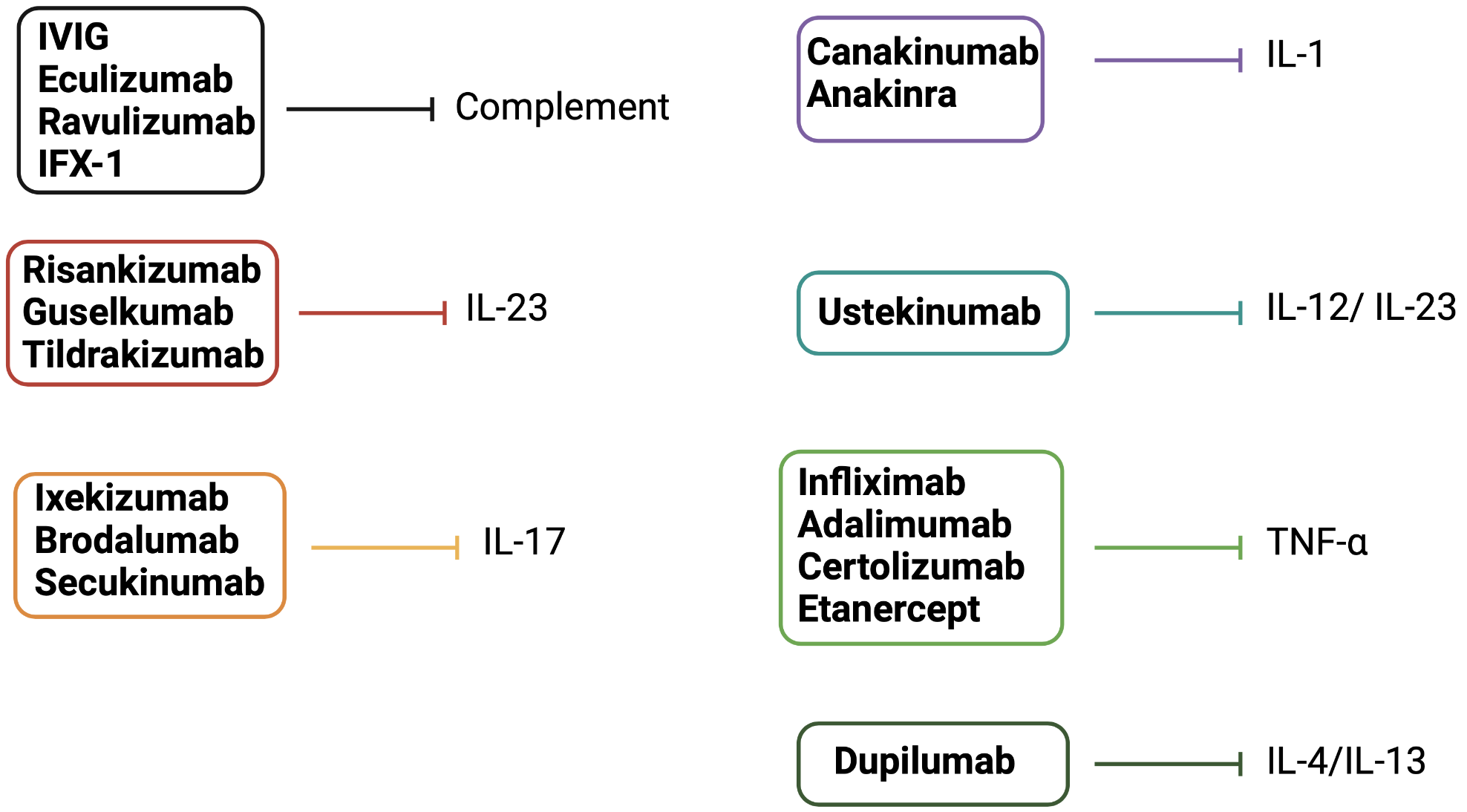

Other interleukin inhibitors were approved for atopic dermatitis and psoriasis (Figure 6). Dupilumab is an IL-4/ IL-13 inhibitor approved in moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis [[97]]. Risankizumab, guselkumab, tildrakizumab (p19 subunit of IL-23 inhibitors), ustekinumab (IL-12/ 23 inhibitor), ixekizumab, brodalumab, and secukinumab (IL-17 inhibitors) are the modern biologics approved in moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. TNF-α inhibitors, such as infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab, and etanercept, may similarly represent a good alternative in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis [[98][99][100][101]]. Most biologics used in psoriasis show no difference regarding short-term efficacy and tolerability [[102]].

Figure 6. Drugs that target innate immunity soluble factors (others than PRRs). Complement modulators and biologics target innate immunity soluble factors. Dupilumab inhibits IL-4/IL-13 and is approved for use in moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. IL-23, IL-17, IL-12/ IL-23 inhibitors, and TNF-α inhibitors are approved for use in moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. Canakinumab and anakinra inhibit IL-1. Eculizumab, ravulizumab, IFX-1, and IVIG inhibit complement pathways.

9. Conclusions

Imiquimod, a TLR-7 ligand, is currently approved for BCC, AK, and condyloma acuminatum, but there is an emerging interest in using imiquimod for other skin cancers, infections, and inflammatory skin conditions. Nevertheless future prospective studies are warranted to provide clear guidelines regarding the off-label uses of Imiquimod. Newly discovered IL-1 inhibitors, canakinumab and anakinra, exhibit a consistent inhibition of the abnormal inflammasome assembly, providing optimistic results in managing patients with CAPS and Schnitzler syndrome. Cytokine inhibitors have opened the door to a new era in treating moderate to severe psoriasis and atopic dermatitis. Given their role in a variety of dermatological diseases, further research is warranted.

References

- Schwartz, T. Immunology. In Dermatology; Bolognia, J.L., Schaffer, J.V., Cerroni, L., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; Chapter 4; pp. 81–83.

- Bonefeld, C.M.; Geisler, C. The role of innate lymphoid cells in healthy and inflamed skin. Immunol. Lett. 2016, 179, 25–28.

- Kabashima, K.; Honda, T.; Ginhoux, F.; Egawa, G. The immunological anatomy of the skin. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2019, 19, 19–30.

- Meyer-Hoffert, U. Innate Immunity in the Skin. J. Innate Immun. 2012, 4, 223–224.

- McKernan, D.P. Pattern recognition receptors as potential drug targets in inflammatory disorders. Adv. Protein Chem. Struct. Biol. 2020, 119, 65–109.

- Ermertcan, A.; Ozturk, F.; Gunduz, K. Toll-like receptors and skin. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2011, 25, 997–1006.

- Wenzel, J. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus: New insights into pathogenesis and therapeutic strategies. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2019, 15, 519–532.

- McInturff, J.E.; Modlin, R.L.; Kim, J. The Role of Toll-like Receptors in the Pathogenesis and Treatment of Dermatological Disease. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2005, 125, 1–8.

- Vignesh, P.; Rawat, A.; Sharma, M.; Singh, S. Complement in autoimmune diseases. Clin. Chim. Acta 2017, 465, 123–130.

- Palianus, J.; Meri, S. Complement System in Dermatological Diseases—Fire Under the Skin. Front. Med. 2015, 2, 3.

- Pasch, M.C.; Bos, J.D.; Daha, M.R.; Asghar, S.S. Transforming growth factor-beta isoforms regulate the surface expression of mem-brane cofactor protein (CD46) and CD59 on human keratinocytes . Eur. J. Immunol. 1999, 29, 100–108, Erratum in Eur. J. Immunol. 1999, 29, 1751.

- Tang, L.; Zhou, F. Inflammasomes in Common Immune-Related Skin Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 882.

- Beer, H.-D.; Contassot, E.; French, L.E. The Inflammasomes in Autoinflammatory Diseases with Skin Involvement. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2014, 134, 1805–1810.

- Broz, P.; Dixit, V.M. Inflammasomes: Mechanism of assembly, regulation and signalling. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2016, 16, 407–420.

- Latz, E.; Xiao, T.S.; Stutz, A. Activation and regulation of the inflammasomes. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2013, 13, 397–411.

- He, Y.; Zeng, M.Y.; Yang, D.; Motro, B.; Núñez, G. NEK7 is an essential mediator of NLRP3 activation downstream of potassium efflux. Nature 2016, 530, 354–357.

- Contassot, E.; Beer, H.-D.; French, L.E. Interleukin-1, inflammasomes, autoinflammation and the skin. Swiss Med Wkly. 2012, 142, w13590.

- Kuemmerle-Deschner, J.B.; Hachulla, E.; Cartwright, R.; Hawkins, P.N.; Tran, T.A.; Bader-Meunier, B.; Hoyer, J.; Gattorno, M.; Gül, A.; Smith, J.; et al. Two-year results from an open-label, multicentre, phase III study evaluating the safety and efficacy of canakinumab in patients with cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome across different severity phenotypes. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2011, 70, 2095–2102.

- Di Micco, A.; Frera, G.; Lugrin, J.; Jamilloux, Y.; Hsu, E.-T.; Tardivel, A.; De Gassart, A.; Zaffalon, L.; Bujisic, B.; Siegert, S.; et al. AIM2 inflammasome is activated by pharmacological disruption of nuclear envelope integrity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, E4671–E4680.

- Yamasaki, K.; Gallo, R.L.; Kenshi, Y.; Richard, L.G. Antimicrobial peptides in human skin disease. Eur. J. Dermatol. EJD 2007, 18, 11–21.

- Gallo, R.L. Sounding the Alarm: Multiple Functions of Host Defense Peptides. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2008, 128, 5–6.

- Kristian, S.A.; Datta, V.; Weidenmaier, C.; Kansal, R.; Fedtke, I.; Peschel, A.; Gallo, R.L.; Nizet, V. D-Alanylation of Teichoic Acids Promotes Group A Streptococcus Antimicrobial Peptide Resistance, Neutrophil Survival, and Epithelial Cell Invasion. J. Bacteriol. 2005, 187, 6719–6725.

- Schauber, J.; Gallo, R.L. Antimicrobial peptides and the skin immune defense system. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2008, 122, 261–266.

- Ong, P.Y.; Ohtake, T.; Brandt, C.; Strickland, I.; Boguniewicz, M.; Ganz, T.; Gallo, R.L.; Leung, D.Y. Endogenous antimicrobial peptides and skin infections in atopic dermatitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002, 347, 1151–1160.

- Herman, A.; Herman, A.P. Antimicrobial peptides activity in the skin. Ski. Res. Technol. 2019, 25, 111–117.

- Heilborn, J.D.; Nilsson, M.F.; Sorensen, O.E.; Ståhle-Bäckdahl, M.; Kratz, G.; Weber, G.; Borregaard, N. The Cathelicidin Anti-Microbial Peptide LL-37 is Involved in Re-Epithelialization of Human Skin Wounds and is Lacking in Chronic Ulcer Epithelium. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2003, 120, 379–389.

- Takeuchi, O.; Akira, S. Pattern recognition receptors and inflammation. Cell 2010, 140, 805–820.

- Charo, I.F.; Ransohoff, R.M. The Many Roles of Chemokines and Chemokine Receptors in Inflammation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 354, 610–621.

- Zhang JM, An J. Cytokines, inflammation, and pain. Int Anesthesiol Clin. 2007 Spring;45(2):27-37. doi: 10.1097/AIA.0b013e318034194e. PMID: 17426506; PMCID: PMC2785020.

- Geginat, J.; Larghi, P.; Paroni, M.; Nizzoli, G.; Penatti, A.; Pagani, M.; Gagliani, N.; Meroni, P.; Abrignani, S.; Flavell, R.A. The light and the dark sides of Interleukin-10 in immune-mediated diseases and cancer. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2016, 30, 87–93.

- Kany S, Vollrath JT, Relja B. Cytokines in Inflammatory Disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2019 Nov 28;20(23):6008. doi: 10.3390/ijms20236008. PMID: 31795299; PMCID: PMC6929211.

- Gröne A. Keratinocytes and cytokines. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2002 Sep 6;88(1-2):1-12. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2427(02)00136-8. PMID: 12088639.

- Sobhan M, Hojati M, Vafaie SY, Ahmadimoghaddam D, Mohammadi Y, Mehrpooya M. The Efficacy of Colloidal Oatmeal Cream 1% as Add-on Therapy in the Management of Chronic Irritant Hand Eczema: A Double-Blind Study. Clin Cosmet Inves-tig Dermatol. 2020 Mar 25;13:241-251. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S246021. PMID: 32273745; PMCID: PMC7103792.

- Artaza-Irigaray C, Molina-Pineda A, Aguilar-Lemarroy A, Ortiz-Lazareno P, Limón-Toledo LP, Pereira-Suárez AL, Ro-jo-Contreras W, Jave-Suárez LF. E6/E7 and E6* From HPV16 and HPV18 Upregulate IL-6 Expression Independently of p53 in Keratinocytes. Front Immunol. 2019 Jul 23;10:1676. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01676. PMID: 31396215; PMCID: PMC6664019.

- Gasque P, Jaffar Bandjee MC, The immunology and inflammatory responses of human melanocytes in infectious diseases, Journal of Infection. 2015, doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2015.06.006.

- Moretti, S., Pinzi, C., Spallanzani, A., Berti, E., Chiarugi, A., Mazzoli, S., Fabiani, M., Vallecchi, C. and Herlyn, M., Im-munohistochemical evidence of cytokine networks during progression of human melanocytic lesions. Int. J. Cancer, 1999, 84: 160-168. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19990420)84:2<160::AID-IJC12>3.0.CO;2-R

- Zhou, J., Yuen, N.K., Zhan, Q. et al. Immunity to the melanoma inhibitor of apoptosis protein (ML-IAP; livin) in patients with malignant melanoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother 61, 655–665 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00262-011-1124-1

- Hartman ML. Non-Apoptotic Cell Death Signaling Pathways in Melanoma. Int J Mol Sci. 2020 Apr 23;21(8):2980. doi: 10.3390/ijms21082980. PMID: 32340261; PMCID: PMC7215321.

- Hänel KH, Cornelissen C, Lüscher B, Baron JM. Cytokines and the skin barrier. Int J Mol Sci. 2013 Mar 26;14(4):6720-45. doi: 10.3390/ijms14046720. PMID: 23531535; PMCID: PMC3645662.

- Braunstein MJ, Kucharczyk J, Adams S. Targeting Toll-Like Receptors for Cancer Therapy. Target Oncol. 2018 Oct;13(5):583-598. doi: 10.1007/s11523-018-0589-7. PMID: 30229471.

- Papakostas D, Stockfleth E. Topical treatment of basal cell carcinoma with the immune response modifier imiquimod. Future Oncol. 2015 Nov;11(22):2985-90. doi: 10.2217/fon.15.192. Epub 2015 Oct 9. PMID: 26450707.

- Huang SW, Wang ST, Chang SH, Chuang KC, Wang HY, Kao JK, Liang SM, Wu CY, Kao SH, Chen YJ, Shieh JJ. Imiquimod Exerts Antitumor Effects by Inducing Immunogenic Cell Death and Is Enhanced by the Glycolytic Inhibitor 2-Deoxyglucose. J Invest Dermatol. 2020 Sep;140(9):1771-1783.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2019.12.039. Epub 2020 Feb 6. PMID: 32035924.

- Jia HX, He YL. Efficacy and safety of imiquimod 5% cream for basal cell carcinoma: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trial. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020 Dec;31(8):831-838. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2019.1638883. Epub 2019 Jul 22. PMID: 31294669.

- Bath-Hextall F, Ozolins M, Armstrong SJ, Colver GB, Perkins W, Miller PS, Williams HC; Surgery versus Imiquimod for Nodular Superficial basal cell carcinoma (SINS) study group. Surgical excision versus imiquimod 5% cream for nodular and superficial basal-cell carcinoma (SINS): a multicentre, non-inferiority, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014 Jan;15(1):96-105. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70530-8. Epub 2013 Dec 11. PMID: 24332516.

- Peris K, Fargnoli MC, Garbe C, Kaufmann R, Bastholt L, Seguin NB, Bataille V, Marmol VD, Dummer R, Harwood CA, Hauschild A, Höller C, Haedersdal M, Malvehy J, Middleton MR, Morton CA, Nagore E, Stratigos AJ, Szeimies RM, Ta-gliaferri L, Trakatelli M, Zalaudek I, Eggermont A, Grob JJ; European Dermatology Forum (EDF), the European Association of Dermato-Oncology (EADO) and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Diagnosis and treatment of basal cell carcinoma: European consensus-based interdisciplinary guidelines. Eur J Cancer. 2019 Sep;118:10-34. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2019.06.003. Epub 2019 Jul 6. PMID: 31288208.

- Ogawa Y, Kawamura T, Matsuzawa T, Aoki R, Shimada S. Recruitment of plasmacytoid dendritic cells to skin regulates treatment responsiveness of actinic keratosis to imiquimod. J Dermatol Sci. 2014 Oct;76(1):67-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2014.07.004. Epub 2014 Jul 19. PMID: 25088809.

- Jansen MHE, Kessels JPHM, Nelemans PJ, Kouloubis N, Arits AHMM, van Pelt HPA, Quaedvlieg PJF, Essers BAB, Steijlen PM, Kelleners-Smeets NWJ, Mosterd K. Randomized Trial of Four Treatment Approaches for Actinic Keratosis. N Engl J Med. 2019 Mar 7;380(10):935-946. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1811850. PMID: 30855743.

- Hadley G, Derry S, Moore RA. Imiquimod for actinic keratosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Invest Dermatol. 2006 Jun;126(6):1251-5. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700264. PMID: 16557235.

- Stockfleth E. Lmax and imiquimod 3.75%: the new standard in AK management. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015 Jan;29 Suppl 1:9-14. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12824. PMID: 25470719.

- Jung JM, Jung CJ, Lee WJ, Won CH, Lee MW, Choi JH, Chang SE. Topically applied treatments for external genital warts in nonimmunocompromised patients: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2020 Jul;183(1):24-36. doi: 10.1111/bjd.18638. Epub 2019 Dec 13. PMID: 31675442.

- Leung AK, Barankin B, Leong KF, Hon KL. Penile warts: an update on their evaluation and management. Drugs Context. 2018 Dec 19;7:212563. doi: 10.7573/dic.212563. PMID: 30622585; PMCID: PMC6302884.

- Akhavan S, Mohammadi SR, Modarres Gillani M, Mousavi AS, Shirazi M. Efficacy of combination therapy of oral zinc sulfate with imiquimod, podophyllin or cryotherapy in the treatment of vulvar warts. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2014 Oct;40(10):2110-3. doi: 10.1111/jog.12457. Epub 2014 Aug 11. PMID: 25132143.

- David CV, Nguyen H, Goldenberg G. Imiquimod: a review of off-label clinical applications. J Drugs Dermatol. 2011 Nov;10(11):1300-6. PMID: 22052312.

- Rosen, T., Harting, M., & Gibson, M. Treatment of Bowen’s Disease with Topical 5% Imiquimod Cream: Retrospective Study. Dermatologic Surgery, 2007, 33(4), 427–432. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2007.33089.x

- Mackenzie-Wood A, Kossard S, de Launey J, Wilkinson B, Owens ML. Imiquimod 5% cream in the treatment of Bowen's disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001 Mar;44(3):462-70. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2001.111335. PMID: 11209116.

- Matuszewski, M., Michajłowski, I., Michajłowski, J., Sokołowska-Wojdyło, M., Włodarczyk, A., & Krajka, K. Topical treat-ment of bowenoid papulosis of the penis with imiquimod. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereolo-gy,2009,23(8), 978–979. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2008.03083.x

- Nunes Mde G, Trope BM, Cavalcanti SM, Oliveira Ldo H, Ramos-e-Silva M. Bowenoid papulosis in a patient with AIDS treated with imiquimod: case report. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2004;12(4):278-81. PMID: 15588562.

- Lim JH, Lim KS, Chong WS. Dramatic clearance of HIV-associated bowenoid papulosis using combined oral acitretin and topical 5% imiquimod. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014 Aug;13(8):901-2. PMID: 25116965.

- Yokoyama, M., Egawa, G., Makino, T., & Egawa, K.. Erythroplasia of Queyrat treated with imiquimod 5% cream: The ne-cessity of regimen guidelines. Clinical Case Reports, 2019, 7(4), 723–725. doi:10.1002/ccr3.2076

- Micali, G., Nasca, M. R., & De Pasquale, R. Erythroplasia of Queyrat treated with imiquimod 5% cream. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 2006, 55(5), 901–903. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2006.07.021

- Pancevski, G., Pepic, S., Idoska, S., Tofoski, G., Nikolovska, S., & Nikolovska, S. Topical Imiquimod 5% as a Treatment Option in Solitary Facial Keratoacanthoma. Open Access Macedonian Journal of Medical Sciences, 2008, 6(3). doi:10.3889/oamjms.2018.133

- Barysch, M. J., Kamarashev, J., Lockwood, L. L., & Dummer, R. Successful treatment of multiple keratoacanthoma with topical imiquimod and low-dose acitretin. The Journal of Dermatology, 2010, 38(4), 390–392. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2010.00967.x

- Tran, D. C., Li, S., Henry, S., Wood, D. J., & Chang, A. L. S. An 18-year retrospective study on the outcomes of kera-toacanthomas with different treatment modalities at a single academic centre. British Journal of Dermatology,2017, 177(6), 1749–1751. doi:10.1111/bjd.15225

- Work Group; Invited Reviewers, Kim JYS, Kozlow JH, Mittal B, Moyer J, Olenecki T, Rodgers P. Guidelines of care for the management of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018 Mar;78(3):560-578. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.10.007. Epub 2018 Jan 10. PMID: 29331386; PMCID: PMC6652228.

- Que SKT, Zwald FO, Schmults CD. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: Management of advanced and high-stage tumors. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018 Feb;78(2):249-261. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.08.058. PMID: 29332705.

- Swetter SM, Tsao H, Bichakjian CK, Curiel-Lewandrowski C, Elder DE, Gershenwald JE, Guild V, Grant-Kels JM, Halpern AC, Johnson TM, Sober AJ, Thompson JA, Wisco OJ, Wyatt S, Hu S, Lamina T. Guidelines of care for the management of primary cutaneous melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 Jan;80(1):208-250. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.08.055. Epub 2018 Nov 1. PMID: 30392755.

- Merritt BG, Degesys CA, Brodland DG. Extramammary Paget Disease. Dermatol Clin. 2019 Jul;37(3):261-267. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2019.02.002. Epub 2019 Apr 19. Erratum in: Dermatol Clin. 2019 Oct;37(4):xiii. PMID: 31084720.

- Odyakmaz Demirsoy E, Bayramgürler D, Çağlayan Ç, Bilen N, Şikar Aktürk A, Kıran R. Imiquimod 5% Cream Versus Cry-otherapy in Classic Kaposi Sarcoma. J Cutan Med Surg. 2019 Sep/Oct;23(5):488-495. doi: 10.1177/1203475419847954. Epub 2019 May 9. PMID: 31072133.

- Shalabi D, Vadalia N, Nikbakht N. Revisiting Imiquimod for Treatment of Folliculotropic Mycosis Fungoides: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2019 Dec;9(4):807-814. doi: 10.1007/s13555-019-00317-2. Epub 2019 Aug 12. PMID: 31407190; PMCID: PMC6828915.

- Sisti A, Sisti G, Oranges CM. Topical treatment of melanoma skin metastases with imiquimod: a review. Dermatol Online J. 2014 Dec 12;21(2):13030/qt8rj4k7r6. PMID: 25756475.

- Gualdi G, Pascalucci C, Panarese F, Prignano F, Giuliani F, Verga E, Amerio P, Verdolini R. Molluscum contagiosum in pediatric patients: to treat or not to treat? Could a personalized imiquimod regimen be the answer to the dilemma? J Der-matolog Treat. 2020 Jun 22:1-6. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2020.1762840. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 32347136.

- Katz KA, Williams HC, van der Wouden JC. Imiquimod cream for molluscum contagiosum: Neither safe nor effective. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018 Mar;35(2):282-283. doi: 10.1111/pde.13398. PMID: 29575068.

- Zhong, C. S., Hasbun, M. T., Jones, K. M., Schmidt, B. A. R., & Hussain, S. H. Pemphigus‐like eruption as a complication of molluscum contagiosum treatment with imiquimod in a 5‐year‐old girl. Pediatric Dermatology., 2020, doi:10.1111/pde.14115

- Sabbagh, F., & Muhamad, I. I. (2017). Acrylamide-based hydrogel drug delivery systems: release of acyclovir from MgO nanocomposite hydrogel. Journal of the Taiwan Institute of Chemical Engineers, 72, 182-193.

- Perkins, N., Nisbet, M., & Thomas, M. Topical imiquimod treatment of aciclovir-resistant herpes simplex disease: case series and literature review. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 2011, 87(4), 292–295. doi:10.1136/sti.2010.047431

- Kan Y, Okabayashi T, Yokota S, Yamamoto S, Fujii N, Yamashita T. Imiquimod suppresses propagation of herpes simplex virus 1 by upregulation of cystatin A via the adenosine receptor A1 pathway. J Virol. 2012 Oct;86(19):10338-46. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01196-12. Epub 2012 Jul 11. PMID: 22787201; PMCID: PMC3457300.

- Jahanban-Esfahlan R, Seidi K, Majidinia M, Karimian A, Yousefi B, Nabavi SM, Astani A, Berindan-Neagoe I, Gulei D, Fallarino F, Gargaro M, Manni G, Pirro M, Xu S, Sadeghi M, Nabavi SF, Shirooie S. Toll-like receptors as novel therapeutic targets for herpes simplex virus infection. Rev Med Virol. 2019 Jul;29(4):e2048. doi: 10.1002/rmv.2048. Epub 2019 Jul 2. PMID: 31265195.

- Valins W, Amini S, Berman B. The Expression of Toll-like Receptors in Dermatological Diseases and the Therapeutic Effect of Current and Newer Topical Toll-like Receptor Modulators. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2010 Sep;3(9):20-9. PMID: 20877521; PMCID: PMC2945844.

- Montes-De-Oca-Sánchez G, Tirado-Sánchez A, García-Ramírez V. Porokeratosis of Mibelli of the axillae: treatment with topical imiquimod. J Dermatolog Treat. 2006;17(5):319-20. doi: 10.1080/09546630600944116. PMID: 17092865.

- Harrison S, Sinclair R. Porokeratosis of Mibelli: successful treatment with topical 5% imiquimod cream. Australas J Dermatol. 2003 Nov;44(4):281-3. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-0960.2003.00010.x. PMID: 14616497.

- Jensen JM, Egberts F, Proksch E, Hauschild A. Disseminated porokeratosis palmaris and plantaris treated with imiquimod cream to prevent malignancy. Acta Derm Venereol. 2005;85(6):550-1. doi: 10.1080/00015550510038241. PMID: 16396815.

- Ahn SJ, Lee HJ, Chang SE, Lee MW, Choi JH, Moon KC, Koh JK. Case of linear porokeratosis: successful treatment with topical 5% imiquimod cream. J Dermatol. 2007 Feb;34(2):146-7. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2006.00236.x. PMID: 17239156.

- Pope E, Doria AS, Theriault M, Mohanta A, Laxer RM. Topical imiquimod 5% cream for pediatric plaque morphea: a pro-spective, multiple-baseline, open-label pilot study. Dermatology. 2011;223(4):363-9. doi: 10.1159/000335560. Epub 2012 Feb 8. PMID: 22327486.

- Dytoc M, Wat H, Cheung-Lee M, Sawyer D, Ackerman T, Fiorillo L. Evaluation of the efficacy and safety of topical imiquimod 5% for plaque-type morphea: a multicenter, prospective, vehicle-controlled trial. J Cutan Med Surg. 2015 Mar-Apr;19(2):132-9. doi: 10.2310/7750.2014.14072. Epub 2015 Mar 11. PMID: 25775634.

- Gül U, Gönül M, Cakmak SK, Kiliç A, Demiriz M. A case of generalized discoid lupus erythematosus: successful treatment with imiquimod cream 5%. Adv Ther. 2006 Sep-Oct;23(5):787-92. doi: 10.1007/BF02850319. PMID: 17142214.

- Turan E, Sinem Bagci I, Turgut Erdemir A, Salih Gurel M. Successful treatment of generalized discoid lupus erythematosus with imiquimod cream 5%: a case report and review of the literature. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2014;22(2):150-9. PMID: 25102804.

- Jiménez-Gallo D, Brandão BJF, Arjona-Aguilera C, Báez-Perea JM, Linares-Barrios M. Imiquimod-induced cutaneous lupus erythematosus with antinuclear antibodies showing a homogenous pattern. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2017 Oct;42(7):795-797. doi: 10.1111/ced.13174. Epub 2017 Jun 14. PMID: 28616880.

- Giang J, Seelen MAJ, van Doorn MBA, Rissmann R, Prens EP and Damman J. Complement Activation in Inflammatory Skin Diseases. Front. Immunol., 2018, 9:639. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00639

- Chimenti MS, Ballanti E, Triggianese P, Perricone R. Vasculitides and the Complement System: a Comprehensive Review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2015 Dec;49(3):333-46. doi: 10.1007/s12016-014-8453-8. PMID: 25312590.

- Ghias MH, Hyde MJ, Tomalin LE, Morgan BP, Alavi A, Lowes MA, Piguet V. Role of the Complement Pathway in In-flammatory Skin Diseases: A Focus on Hidradenitis Suppurativa. J Invest Dermatol. 2020 Mar;140(3):531-536.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2019.09.009. Epub 2019 Dec 20. PMID: 31870626.

- ClinicalTrials.gov. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03001622 (accessed on 12 August 2021).

- De Benedetti F, Gattorno M, Anton J, Ben-Chetrit E, Frenkel J, Hoffman HM, Koné-Paut I, Lachmann HJ, Ozen S, Simon A, Zeft A, Calvo Penades I, Moutschen M, Quartier P, Kasapcopur O, Shcherbina A, Hofer M, Hashkes PJ, Van der Hilst J, Hara R, Bujan-Rivas S, Constantin T, Gul A, Livneh A, Brogan P, Cattalini M, Obici L, Lheritier K, Speziale A, Junge G. Cana-kinumab for the Treatment of Autoinflammatory Recurrent Fever Syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2018 May 17;378(20):1908-1919. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1706314. PMID: 29768139.

- Betrains A, Staels F, Vanderschueren S. Efficacy and safety of canakinumab treatment in schnitzler syndrome: A systematic literature review. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2020 Aug;50(4):636-642. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2020.05.002. Epub 2020 May 25. PMID: 32502728.

- Kolios AG, Maul JT, Meier B, Kerl K, Traidl-Hoffmann C, Hertl M, Zillikens D, Röcken M, Ring J, Facchiano A, Mondino C, Yawalkar N, Contassot E, Navarini AA, French LE. Canakinumab in adults with steroid-refractory pyoderma gangrenosum. Br J Dermatol. 2015 Nov;173(5):1216-23. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14037. Epub 2015 Oct 16. PMID: 26471257.

- Sun NZ, Ro T, Jolly P, Sayed CJ. Non-response to Interleukin-1 Antagonist Canakinumab in Two Patients with Refractory Pyoderma Gangrenosum and Hidradenitis Suppurativa. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2017 Sep;10(9):36-38. Epub 2017 Sep 1. PMID: 29344326; PMCID: PMC5749618.

- Leslie KS, Tripathi SV, Nguyen TV, Pauli M, Rosenblum MD. An open-label study of anakinra for the treatment of moderate to severe hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014 Feb;70(2):243-51. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.09.044. Epub 2013 Dec 4. PMID: 24314876.

- Seegräber M, Srour J, Walter A, Knop M, Wollenberg A. Dupilumab for treatment of atopic dermatitis. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2018 May;11(5):467-474. doi: 10.1080/17512433.2018.1449642. Epub 2018 Mar 20. PMID: 29557246.

- Papp KA, Blauvelt A, Bukhalo M, Gooderham M, Krueger JG, Lacour JP, Menter A, Philipp S, Sofen H, Tyring S, Berner BR, Visvanathan S, Pamulapati C, Bennett N, Flack M, Scholl P, Padula SJ. Risankizumab versus Ustekinumab for Moder-ate-to-Severe Plaque Psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2017 Apr 20;376(16):1551-1560. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1607017. PMID: 28423301.

- Deodhar A, Gottlieb AB, Boehncke WH, Dong B, Wang Y, Zhuang Y, Barchuk W, Xu XL, Hsia EC; CNTO1959PSA2001 Study Group. Efficacy and safety of guselkumab in patients with active psoriatic arthritis: a randomised, double-blind, pla-cebo-controlled, phase 2 study. Lancet. 2018 Jun 2;391(10136):2213-2224. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30952-8. Epub 2018 Jun 1. PMID: 29893222.

- Bai F, Li GG, Liu Q, Niu X, Li R, Ma H. Short-Term Efficacy and Safety of IL-17, IL-12/23, and IL-23 Inhibitors Brodalumab, Secukinumab, Ixekizumab, Ustekinumab, Guselkumab, Tildrakizumab, and Risankizumab for the Treatment of Moderate to Severe Plaque Psoriasis: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J Immunol Res. 2019 Sep 10;2019:2546161. doi: 10.1155/2019/2546161. PMID: 31583255; PMCID: PMC6754904.

- Armstrong AW, Read C. Pathophysiology, Clinical Presentation, and Treatment of Psoriasis: A Review. JAMA. 2020 May 19;323(19):1945-1960. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4006. PMID: 32427307.

- Mahil SK, Ezejimofor MC, Exton LS, Manounah L, Burden AD, Coates LC, de Brito M, McGuire A, Murphy R, Owen CM, Parslew R, Woolf RT, Yiu ZZN, Uthman OA, Mohd Mustapa MF, Smith CH. Comparing the efficacy and tolerability of biologic therapies in psoriasis: an updated network meta-analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2020 Oct;183(4):638-649. doi: 10.1111/bjd.19325. Epub 2020 Aug 9. PMID: 32562551.