To evaluate the repair performance of HSGc-C5 carcinoma cell against radiation-induced DNA damage, a Geant4-DNA application for radiobiological research was extended by using newly measured experimental data acquired.

1. Incident Energy Spectra at the Cell Entrance

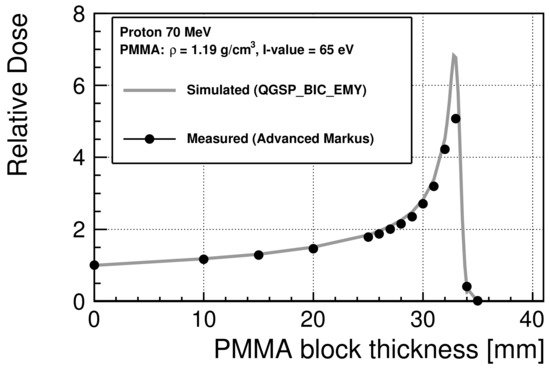

To estimate the energy spectra of the incident protons at the cell entrance in the irradiation experiments for the colony assay and FAR assay, the I-value of the PMMA used in the experiments was evaluated to be 65 eV to provide the best agreement with the measured depth dose as the I-value. Figure 2 shows the relative dose distribution of 70 MeV protons scaled at 0 mm. The maximum standard errors of the experimental data are 0.27% before the Bragg peak and 8% after the peak. The Bragg peak occurred between 32 mm and 33 mm.

Figure 2. Relative dose of 70 MeV protons in PMMA scaled at 0 mm. The statistical uncertainties are smaller than the marker size.

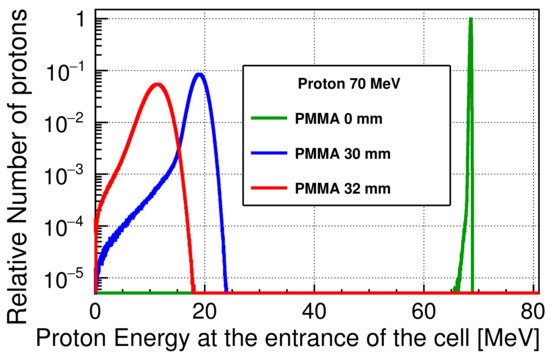

Figure 3 shows the energy spectra of the incident protons at the entrance of the cell, scaled to the maximum of the number of protons at a 0 mm PMMA thickness. The energy is shifted to lower values with increasing PMMA thickness reaching 10.8 MeV at 32 mm, and the width of a spectrum broadens due to the energy losses and energy straggling while passing through the PMMA. Even when the PMMA block is not inserted, the protons will lose their energy when passing through the PMMA sheet and the window of the advanced Markus chamber. The average proton energies were approximately 68.5, and 10.8 MeV, and the standard deviations of the spectra were 0.5 and 2.1 MeV at PMMA thicknesses of 0 and 32 mm, respectively. The corresponding unrestricted linear energy transfer (LET

∞) values were 0.05, 0.60, and 0.96 keV/

μm

[1][58], respectively.

Figure 3. Scaled energy spectra of the 70 MeV incident protons at the cell entrance, downscaled by a PMMA block and a PMMA sheet. The thickness of the PMMA sheet is not considered in the figure legend.

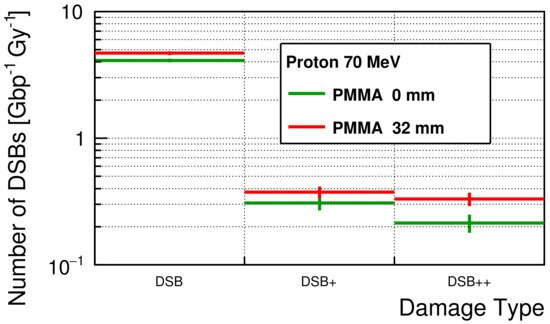

2. Initial DNA Damage

The simulated initial number of DSBs for each damage type is shown in Figure 4. For all damage types, the numbers of DSBs were slightly larger with a 32 mm PMMA block than the numbers without a PMMA block. The average numbers of DSBs were 4.11 ± 0.14 and 0.74 ± 0.11 Gy−1Gbp−1 for simple-DSB and complex-DSB without a PMMA block, respectively. With a PMMA block, the average numbers of DSBs were 4.69 ± 0.17 and 1.04 ± 0.12 Gy−1Gbp−1, respectively.

Figure 4. The simulated number of DSBs for each damage type.

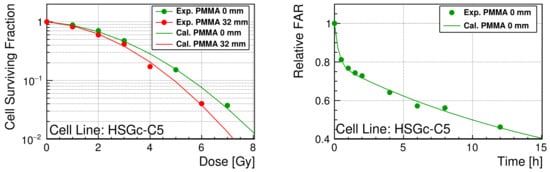

3. Optimized Repair Performance

As shown in Figure 5, the model parameters of the TLK model are reasonably optimized for the Geant4-DNA to reproduce both SF and relative FAR.

Figure 5. (

Left): SF of HSGc-C5 as a function of delivered dose. The statistical errors were smaller than the marker size (up to 7%). (

Right): Relative FAR of HSGc-C5 as a function of time after irradiation. The curve is calculated with the optimized TLK model parameters from the simulated initial DNA damage. The measured SF and relative FAR are available in

supplementary materials SF.csv and FAR.csv.

The optimized parameters are presented in Table 1. Through the fast-repair process, the probability of the repair was approximately 3.36 h−1 (the half-life time is approximately 12.6 min). Through the slow-repair process, the probability of the repair was approximately 0.01 h−1 (the half-life time is approximately 70.0 h). The probability of the binary repair was significantly small (4.58×10−6 h−1) relative to that of single rejoining. In contrast, the lethality of binary repair was very high (probability of repair leading cell death, possibly misrepair, in the binary repair process ∼40%). Compared with the lethality of binary repair, the lethality of residual complex DSBs was relatively small (∼3%).

Table 1. Optimized repair parameters for HSGc-C5.

| λ1 | (h | −1 | ) |

λ2 | (h | −1 | ) |

η | (h | −1 | ) |

β1 |

β2 |

γ |

| 3.36 |

0.99×10−2 |

4.58×10−6 |

0. |

2.75×10−2 |

0.39 |

4. Conclusion

To evaluate the repair performance of HSGc-C5 cell against radiation induced DNA damage, the Geant4-DNA application was extended by using newly measured experimental data acquired in this study. Concerning fast- and slow-DNA rejoining, the TLK model parameters were adequately optimized (the repair speeds of each process were reasonably close to the DNA rejoining speed of the NHEJ and HR processes). The lethality rates of the DNA damage induced by complex DSBs and binary repair were approximately 3% and 40%, respectively. Using the optimized repair parameters, the Geant4-DNA simulation was able to predict the SF and the DNA repair kinetics.