Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Jessie Wu and Version 4 by Jessie Wu.

Academic interest in the involvement of indigenous peoples with tourism has grown considerably over the past two decades, but the focus has been on traditional activities and facilities and there is little tourism literature which looks at non-traditional forms of tourism involvement. The entry suggests this reflects the motivations and interests of researchers and suggests that increased indigenous participation in research is to be encouraged and may be reflected in different emphases and subjects.

- economic development

- indigenous peoples

- tourism

1. Background

Indigenous tourism is a term commonly used to describe tourism that involves indigenous peoples or first nations in tourism. In recent years, research attention on this topic has broadened and expanded greatly, reflecting both increased involvement of indigenous peoples and their more active participation in controlling and utilising a widening range of tourism and economic development. This more active participation has taken tourism beyond its traditional role as a limited source of employment and economic development to a stage at which tourism is being utilised as an agent to improve the indigenous political position with respect to controlling a wider range of development and strengthening regional and national identities.

2. Stages of and Motivation for Involvement

It is not unreasonable to propose that part of this neglect and narrowness of focus of the economic aspect of such involvement may lie in the motivations of the various parties which established tourist visitation to indigenous peoples. The involvement of tourism with indigenous peoples in various forms is older than may be imagined. Weaver [1] argued that “indigenous tourism” had gone through six phases, which he called pre European; exposure; exhibitionism and exploitation (with artefacts in museums etc.); exhibitionism and exploitation in remnant areas and resistance; empowerment, and finally; quasi empowerment and “shadow indigenous tourism”. In his discussion of this categorization, Weaver does not discuss economic development or business opportunities specifically, rather focusing on the social and cultural issues resulting from the interaction between indigenous and non-indigenous groups, or “hosts and guests” to use Smith’s terminology [2].

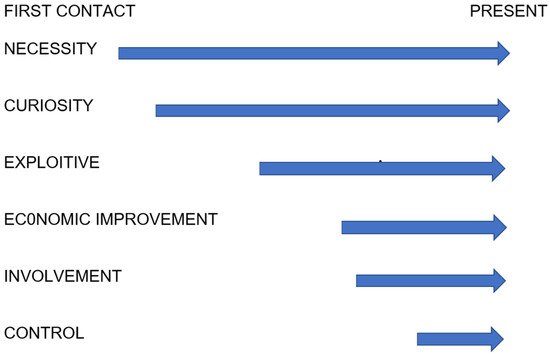

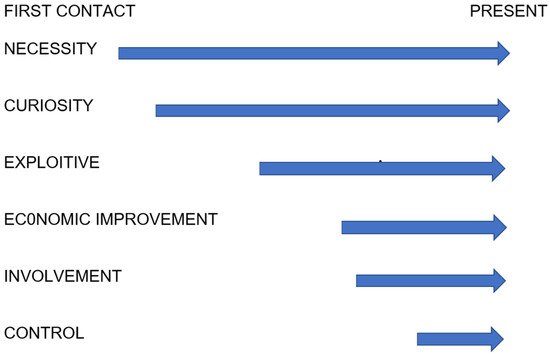

In taking an alternative view, it is possible to suggest that the interaction of tourists and indigenous peoples was influenced by a broader set of motivations, particularly on the part of the non-indigenous populations involved, as illustrated in Figure1. This figure illustrates the increasing range of motivations involved in tourism to indigenous peoples from the time of first contact between indigenous groups and visitors. Precise timelines are not feasible to portray because of the great variation in individual cases, reflecting factors including accessibility, remoteness, policies of governments and indigenous groups about allowing contact and under what conditions, and the rate of tourism development in general in specific areas. In some cases indigenous populations have had a long period of contact with outside peoples and tourists and a variety of motivations for that contact, in other cases, the time period between first contact and the present day may be only a century or even less.

Figure 1.

Changing motivations for tourism involvement with indigenous peoples.

It can be argued that the first motivation for tourist-related contact was Obligation or Necessity, a need for people to know of other cultures. This motivation was found in the elite of society of the time, in the form of the first tourists of the Grand Tour in Europe in the 1600s [3] although the perceptions of these other cultures varied from viewing them as examples of how one should behave, to one of disrespect. That motivation moved to Curiosity, particularly as tourism spread to remoter parts of the world (in the perceptions of tourist generating countries) and contact with indigenous peoples became more frequent, reflecting such forces as colonialism, much-improved transportation services, and the development of international economic linkages [4]. This marked the beginning of economic motivations for visiting indigenous peoples and was stimulated and marketed by companies and individuals who saw economic benefits from increased business in fields such as transportation and accommodation, and their early customers were again the affluent segments of societies. In turn to this was added Exploitation, primarily by non-indigenous agencies who foresaw economic benefits to their stakeholders from taking tourists to view indigenous peoples in their settings. This motivation was almost entirely economic, involving enterprises such as the Canadian Pacific Railway in Canada and its equivalents in the west of the United States, major shipping lines such as Pacific and Orient (P&O) trading across the Pacific in particular [4], and to a much lesser degree, international airlines and tour companies. Some of the early tour companies, such as Thomas Cook, had already begun to offer tours to “foreign lands” which also encourage visitation to local communities to “see the natives”, who were promoted as features of interest. The role of indigenous communities in these stages was almost entirely passive, providing an attraction and gaining very little in terms of employment or from sales of products.

This period was followed by Economic Improvement, with governments (regional and national) and supporting agencies at national and international levels encouraging indigenous tourism as a way of reducing poverty amongst indigenous peoples, albeit with concerns over potential negative impacts of the development of tourism. Johnston ([5], p.89) for example, noted “The tourism industry, especially ecotourism, is arguably the prime force today threatening indigenous homelands and cultures”. At this stage, participation was sometimes initiated by indigenous communities themselves, realizing that there were opportunities for economic development that could be controlled by the local communities themselves and thus directed to meet local needs and preferences [6][7][8]. Such developments could then be aimed at maximizing benefits while specifically avoiding potential conflicts over resource use, exploitation of traditions, and cultural misappropriation. The Maori at the hot springs at Rotorua in New Zealand, are one example, building on the established pattern of tourist visitation to the geothermal terraces first visited by tourists at the end of the nineteenth century [9]. Initially, however, almost all of the economic development was related directly to traditional activities, products and culture, albeit under partial or complete indigenous control.

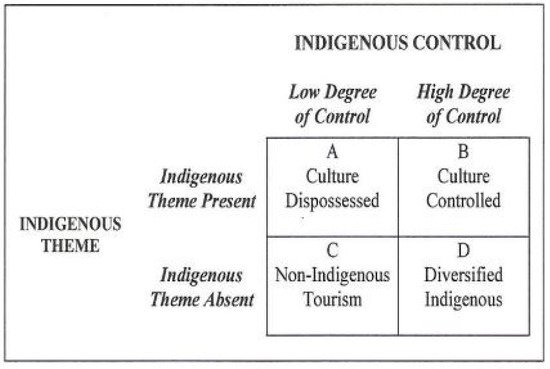

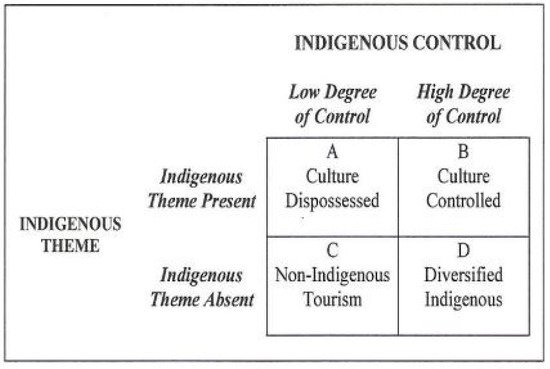

This pattern fits the model of Butler and Hinch [10] whereby the degree of control of indigenous tourism can shift from a low level to a high level (Figure 2). At the same time, there was the slight emergence of involvement in the economic development of tourism that went beyond the “culture dispossessed” element of that model to what is shown in that figure as “diversified indigenous tourism”. This represents the beginning of a major and significant change in indigenous peoples’ involvement in tourism, into the stage of Involvement, by their participating in the economic development of tourism that was indigenous in control and ownership but not related to indigenous culture to any significant degree. It is this element that is relatively lacking in the tourism literature that was reviewed compared to other foci. This stage reflects the beginning of tourism to indigenous communities initiated by themselves, both to showcase their cultures and practices, but also reflecting an interest in the economic benefits potentially available. Involvement had long been a feature of indigenous tourism, but primarily as an element being observed rather than as an agent of development, the latter traditionally remaining under the control of external agencies, both public and private. The shift in emphasis came about for a number of reasons, including improved access to previously relatively remote indigenous locations, greater interest in traditional cultures, and greater publicity and promotion of indigenous attractions. From being passive attractions, indigenous populations began to participate actively, as guides, information sources, educators, and facility owners and operators as involvement grew. This situation also saw increasing issues and problems, such as clashes over behaviour, over access to specific areas and resources and over cultural disagreements. One good example of such issues was access to Uluru (Ayers Rock) in central Australia. Uluru had become a major tourist attraction once access was available by road and air, and accommodation provided. One of the tourist attractions was climbing the rock, an activity opposed by the local tribe (Anangu) who regarded the monolith as a sacred feature. It took many years of protest, despite Uluru being in a national park, created by the courtesy of the local people, to end the practice [11], reflecting not only greater involvement in management by the local aboriginals but also their re-gaining an element of control over the nature and scale of development.

Figure 2.

Matrix of control and theme.

The final stage of the process being discussed is that of Control of indigenous tourism by indigenous peoples. It is important to recognize that control in this situation does not mean only control of what had become traditional tourist activities on indigenous lands, but also control over non-traditional indigenous tourist activities and related services including transportation and accommodation at all scales and not necessarily in traditional forms. In some cases, this has meant indigenous communities becoming engaged in the economic development of tourism outwith their traditional reservations and very clearly engaged in forms of tourism with little or no links to indigenous traditions. This is a logical progression by a section of the population in many countries which had previously been denied access to the control and direction of tourism and other economic development. Such denial in many cases was by both neglect and by a misperception of their abilities and inclinations, as well as deliberate suppression, thus preventing an appropriate level of involvement in the economic development of tourism. Catellino ([12], p. 274) summed up the situation in North America “With ongoing consequences for American Indians, the New World Indian has been a pervasive figure of constitutive exclusion in modern theories of money, property, and government”. The most obvious example of broadening of involvement is probably in the area of casino expansion in the United States of America, with the attendant benefits and problems which have ensued [13]. Major changes in the legal arrangements for gambling in the United States were undertaken in the 1970s which resulted in two significant impacts for indigenous communities and their economic development [14]. In the first case, the monopoly on gambling held by Nevada was broken with gambling being allowed, under varying degrees of control, in all states, and secondly, gambling was legally permitted on Indian Reservations. The implications and changes which the relevant legislation brought about were massive for many indigenous groups [15], and illustrated what could be achieved in terms of potential economic development in previously “useless” areas and how such development could take place under indigenous control. Little of this is discussed in the tourist academic literature ([16] is somewhat of an exception), where the focus has remained on culture and tradition and associated forms of tourism development and its implications [17]. There is considerable discussion of these alternative economic developments related to tourism in other literature [12][18][19][20] under such search topics as “indigenous peoples and casinos” (183 references in SCOPUS for example), although much of that is focused on the negative aspects of such developments (e.g., [18]).

It is important to note that each of the motivations identified in Figure 2 above have tended to remain present as an influence on tourism visitation, although several have diminished in relative importance over time. It would be wrong, for example, to imagine that the curiosity element has disappeared, and, for better or worse, it is likely to remain a factor in explaining why some tourists want to visit indigenous peoples. The lure of the “perceived exotic” is powerful and present in many forms of tourism and particularly strong where the exotic is becoming increasingly easy to access [4] and no longer threatening in the way it may have been perceived in the nineteenth century when the first major contacts were made in a tourism context between visitors and indigenous communities.

3. Current Insight into Tourism, Indigenous Peoples

As knowledge about tourism and its effects became more accurate and detailed, the more complex relationships that exist between tourism and its associated development and indigenous communities can be identified. There has been a growth in research on how indigenous communities could become involved in tourism for purposes of economic development and employment, and subsequently on the difficulties and problems such a step involves. A matrix used in Tourism and Indigenous Peoples [10] (Figure 2) placed the focus on control and the theme involved in indigenous tourism. It can be argued that there has been a trend from Culture Dispossessed (low indigenous control with an indigenous theme) to Culture Controlled (an indigenous theme with a high indigenous level of control) and to Diversified Indigenous (high indigenous control but without an indigenous theme). It is important to re-emphasise as well, the considerable and growing involvement in what was termed Non-Indigenous Tourism, where indigenous control was low and there was no indigenous theme, as represented, for example, in some casino developments and other forms of mass tourism on indigenous land, which potentially offers considerable basic employment for indigenous peoples that would otherwise be absent. Emphasis has also shifted to social and cultural responses to involvement in tourism, including changes in behaviour, such as modification of cultural practices and products for sale to tourists, and ways in which indigenous communities could shield themselves from the more intrusive aspects of tourism. As noted, there has been increasing interest in the politics and power aspects of indigenous involvement with tourism [21]. This discussion includes who controls tourism and its entry into indigenous communities and areas under indigenous control, what indigenous communities feel its role should be in their homelands, and most importantly, who decides on the nature, rate and level of development of tourism in such situations. The inclusion of tourism in discussions relating to indigenous rights and nationalism represents perhaps the latest area of academic discussion [22]. As with all aspects of development, control and power lie at the heart of the rationale for and the effects of development and change on all communities. Comments on academic research made earlier note that traditionally much research has been performed by researchers for their own purposes. Some have participated with such groups in gathering data, formulating hypotheses and deducing implications and suggested actions, reflecting an increasing interest in the use of local indigenous knowledge in forms of economic development such as tourism [23]. Such research in the future should include a wider range of potential economic development that could be used by indigenous peoples should they so desire. This last point is critical, the decision on what level, what type and what rate of economic development should take place, if any at all, should clearly be made by the indigenous communities involved rather than by external agencies, public or private. To argue otherwise is to revert to the worse patriarchal forms of colonialism where economic development was dominated by the benefits which accrue to external stakeholders, sometimes in conflict with the wishes of the local inhabitants. Excluding considering or not offering a full range of potential forms of economic development is inappropriate and implies that only certain, externally approved types of development should be promoted and allowed for indigenous populations. Research on and for indigenous peoples with respect to tourism has an obligation to be comprehensive and not pre-ordained by external views on sustainability, ecotourism, or other concepts, and must allow the indigenous populations to be involved from the very beginning of any proposals for development. Where such research involves indigenous peoples, acquiring and using their knowledge [24] in the research also creates an obligation to produce results that could be of value to the indigenous community. This may mean that the results have to be written and presented in forms that are useful to those communities and not just to an academic audience in line with academic paradigms. Incorporating indigenous scholars in collaborative research studies is one essential step in producing more relevant and useful results.4. Summary

Smmary

Whitford and Ruhanen ([25], p. 1091) concluded their paper with some powerful statements, including “primary consideration at all times should be how and what do (Indigenous Peoples) want from Indigenous tourism”, and that research “should be guided by Indigenous peoples and cultures…-and not the academy”. Those sentiments are still pertinent and deserve emphasis. It can be argued that too much tourism research on issues relating to indigenous tourism, particularly in the past, was carried out with little knowledge or experience of tourism and as a result, conclusions were drawn that could not be defended in the current era. The impacts caused by tourism are complex as well as indirect, and spatially and temporally variable. Things blamed on tourism and benefits ascribed to tourism development can be misplaced and misinterpreted. Impacts can take a long time to appear, some are incidental, and some appear only in other locations, thus extensive knowledge of tourism itself and what its development means is vitally important if appropriate conclusions are to be drawn about its effects, positive and negative, on indigenous peoples.

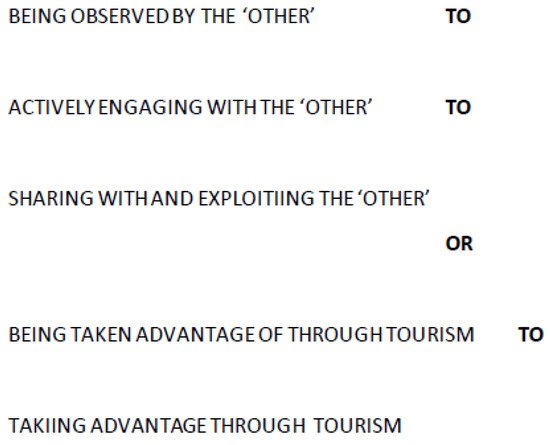

The general future for indigenous tourism is likely to be positive, both in the level of engagement and hopefully, in indigenous control and management over such development. The increasing involvement of indigenous people in research is certain to bring with it not only a greater representation of indigenous views but also increasing recognition for those viewpoints. This is particularly important with respect to the portrayal of indigenous communities and their culture, a major problem in earlier times when the representation of indigenous peoples was incorrect and often unethical, as well as disrespectful in many ways. More research and knowledge are needed in making the move from “Being observed by the Other” to “Actively engaging with the Other” to “Sharing with and Exploiting the Other” (Figure 34), and ensuring this move is as easy as possible for communities involved. The shift from being taken advantage of through tourism to appropriately taking advantage through tourism requires more research on the full range and appropriate forms of tourism as viewed by indigenous communities and how their specific goals and preferences can be achieved. Among these goals are achieving greater equity and equality, as well as much greater control over the nature and scale of all developments. Such research inevitably means shared participatory efforts led by indigenous knowledge and wishes.

Figure 34. Changing roles and relationships in indigenous tourism.

References

- Weaver, D. Indigenous tourism stages and their implications for sustainability. J. Sustain. Tour. 2010, 18, 43–60.

- Smith, V. Hosts and Guests: The Anthropology of Tourism; University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1977.

- Hibbert, C. The Grand Tour; George Putnam and Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1974.

- Douglas, N. They Came for Savages. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia, 1994.

- Johnston, A. Indigenous Peoples and Ecotourism: Bringing Indigenous Knowledge and Rights into the Sustainability Equation. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2000, 25, 89–96.

- Carr, A. Maori nature tourism businesses: Connecting with the land. In Tourism and Indigenous Peoples Issues and Implications; Butler, R., Hinch, T., Eds.; Butterworth Heinemann: London, UK, 2007; pp. 113–127.

- Blundell, V. Aboriginal empowerment and souvenir trade in Canada. Ann. Tour. Res. 1993, 20, 64–87.

- Wherry, F.F. The Nation state, identity management and indigenous crafts: Constructing markets and opportunities in North West Costa Rica. Ethn. Racial Stud. 2006, 29, 1124–1152.

- Hall, M.C. Tourism and the Maori of Aotearoa. In Tourism and Indigenous Peoples; Butler, R., Hinch, T., Eds.; Thompson International Business Press: London, UK, 1996; pp. 155–175.

- Butler, R.W.; Hinch, T. 1996. Available online: https://catalogue.nla.gov.au/Record/1261873 (accessed on 28 November 2021).

- King, J. Indigenous Tourism: The Most Ancient of Journeys. In Tourism and Religion Issues and Implications; Butler, R., Suntikul, W., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 14–17.

- Cattelino, J.R. From Locke to slots: Money and the politics of indigeneity. Comp. Stud. Soc. Hist. 2018, 60, 274–307.

- Jojola, T.; Ong, P. Indian gaming as community economic development. In Jobs and Economic Opportunities in Minority Communities; Ong, P., Loukaitou-Suderis, A., Eds.; A Temple Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2006; pp. 213–231.

- Stansfield, C. Reservations and Gambling: Native Americans and the diffusion of legalised gaming. In Tourism and Indigenous Peoples; Butler, R., Hinch, T., Eds.; International Thompson Business Press: London, UK, 1996; pp. 129–147.

- Carmichael, B.; Jones, J.L. Indigenous owned casinos and perceived local community impacts. In Tourism and Indigenous Peoples Issues and Implications; Butler, R., Hinch, T., Eds.; Butterworth Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2007; pp. 95–109.

- Ruhanen, L.; McLennan, C.; Whitford, M. Developing a sustainable indigenous tourism sector: Reconciling socio-economic objectives with market driven approaches. In Indigenous People and Economic Development: An International Perspective; Hassan, A., L’Abee, R., Iankova, K., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 205–221.

- Grimwood, B.S.R.; Muldoon, M.L.; Stevens, Z.M. Settler colonialism, Indigenous cultures, and the promotional landscape of tourism in Ontario, Canada’s ‘near North’. J. Herit. Tour. 2019, 14, 233–248.

- Kovas, A.E.; McFarland, B.H.; Landen, M.G.; Lopez, A.L.; May, P.A. Survey of American Indian alcohol statutes, 1975–2006: Evolving needs and future opportunities for tribal health. J. Stud. Alcohol. Drugs 2008, 69, 183–191.

- Matelski, M.J.; Street, N.L. The passamaquoddy indians: Casinos, controversy, and creative apparel. Int. J. Civ. Political Community Stud. 2014, 12, 21–32.

- McMillen, J.; Donnelly, K. Gambling in Australian Indigenous communities: The state of play. Aus. J. Social Issues 2008, 43, 397–446.

- Brougham, J.E.; Butler, R.W. The Application of Segregation Analysis to Explain Resident Attitudes to Social Impacts of Tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1981, 8, 569–590.

- Takele, Y.S. Community based eco-tourism as a biodiversity conservation and livelihood option in rural ethiopia: A case study on mountain abuna yosef and its surrounding area, north wollo. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Syst. 2019, 12, 36–50.

- Hall, M.C. Politics, power and indigenous tourism. In Tourism and Indigenous Peoples; Butler, R.W., Hinch, T., Eds.; Butterworth Heinemann: London, UK, 2007; pp. 305–319.

- Butler, C.F.; Menzies, M.C.R. Traditional ecological knowledge and indigenous tourism. In Tourism and Indigenous Peoples Issues and Implications; Butler, R., Hinch, T., Eds.; Butterworth Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2007; pp. 15–27.

- Whitford, M.; Ruhanen, L. Indigenous tourism research, past and present: Where to from here? J. Sustain. Tour. 2016, 24, 1080–1099.

More