Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Bruce Ren and Version 1 by Emilia Sawicka.

Cardiovascular diseases are the most common causes of hospitalization, death and disability in Europe. Despite our knowledge of nonmodifiable and modifiable cardiovascular classical risk factors, the morbidity and mortality in this group of diseases remains high, leading to high social and economic costs. Therefore, it is necessary to explore new factors, such as the gut microbiome, that may play a role in many crucial pathological processes related to cardiovascular diseases. Diet is a potentially modifiable cardiovascular risk factor. Fats, proteins, carbohydrates, vitamins and minerals are nutrients that are essential to the proper function of the human body.

- gut microbiome

- diet

- heart

- cardiovascular risk factors

- cardiovascular diseases

1. Introduction

Cardiovascular pathologies, among non-infectious diseases, are significant causes of mortality (49% of all deaths) [1]. Annually, 4 million deaths in Europe are attributed to these diseases and cardiovascular mortality is higher in Central and Eastern Europe compared with Western Europe [1]. Despite our knowledge of nonmodifiable and modifiable cardiovascular classical risk factors, reliably described in Framingham’s cohort study [2], the morbidity and mortality in this group of diseases remains high [3]. Due to the above-mentioned reasons, and the high social and economic costs related to this group of diseases, it is necessary to explore other factors, such as the gut microbiome, that may play a role in many crucial pathological processes in the cardiovascular system. The data from the literature revealed that bacteria form an interactive ecosystem of interdependencies with their host cells in the majority of cases, in the form of mutualism and commensalism [4,5,6][4][5][6]. This influences the immune processes of the host as well as metabolic homeostasis, and is therefore an important element in cardiovascular disease development and progression [7]. Diet is a cardiovascular risk factor that may be easily modifiable. The relationship between the gut microbiome, diet and cardiovascular disease is complex and still not fully understood.

The human microbiome is formed shortly after birth and in healthy individuals this process is largely completed within the first 3–5 years; however, it can be modified by diet [8,9][8][9]. Fats, proteins, carbohydrates and vitamins are nutrients that are essential to the proper functioning of the human body. The style and composition of the human diet has changed over time and evolved from a hunter–gatherers diet to an industrialized and Westernized modern diet including processed products and fast food. It is suggested that gut microbiota are involved in energy homeostasis by extracting calories from nutrients and in the metabolism of short-chain fatty acids, amino acids and vitamins [5].

2. Diet pattern

2.1. Traditional vs. Modern Industrialized Diet

The industrialization of European countries has resulted in an increased amount of fat in our diet, and a reduction in complex carbohydrate consumption, which has led to a decrease in gut microbiome diversity [10]. It was found that African children from rural villages, in contrast to European populations, showed a significant enrichment in phylum Bacteroidetes and a depletion in Firmicutes, and the family of Enterobacteriaceae from the phylum Proteobacteria, with a unique abundance of bacteria from the genera Prevotella and Xylanibacter. The latter contains a set of bacterial genes for cellulose and xylan hydrolysis that are completely missing in European children [10]. Furthermore, their diet was rich in short-chain fatty acids [10]. Differences in the gut microbiome and metabolomics profile between unindustrialized, traditional rural lifestyles (Hadza hunter-gatherers of Tanzania) and the industrialized, Westernized diet and lifestyles of urban Italians were found [10,11,12,13][10][11][12][13]. The Hadza diet consists of wild foods that can be classified into five main categories: meat, honey, baobab, berries and tubers, without cultivated or domesticated plants and animals, and minimal amounts of agricultural products, whereas the diet of the Italian cohort is almost entirely composed of commercial agricultural products and adheres to the Mediterranean diet, which includes abundant plant foods, fresh fruit, pasta, bread and olive oil [11]. The study revealed higher abundance of Bacteroidetes and a lower abundance of Firmicutes in the Hadza population compared to the Italian group, and the near absence of Actinobacteria, an important subdominant component, in the Italian microbiome [11]. Furthermore, the Hadza gut microbial ecosystem was profoundly depleted in Bifidobacterium, enriched in Prevotella, and comprised of unusual arrangement of Clostridiales [11]. Moreover, a review by García-Montero et al. did not compare specific diets related to particular environmental factors but rather nutritional approaches such as the Mediterranean and Westernized diet [14]. Based on a PREDIMED (PREvención con DIeta MEDiterránea) study, the authors concluded that participants with better adherence to the Mediterranean diet, who consumed more polysaccharides and plant proteins and less animal protein [15] and those with reduced animal protein in their diet, presented a higher abundance of Bacteroidetes with a lower Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio [14,15][14][15]. This diet pattern was related to greater diversity, and an improved gut barrier function and permeability [16]. Participants who consumed greater amounts of animal protein differed from the Mediterranean diet and were characterized by a higher Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio [14,15][14][15].

The Westernized diet is characterized by a high content of unhealthy and harmful elements along with a reduced consumption of fruits and vegetables. This dietary approach promotes a pathological microbiota status, leading to a higher Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio [14].

What Does It Mean for the Heart?

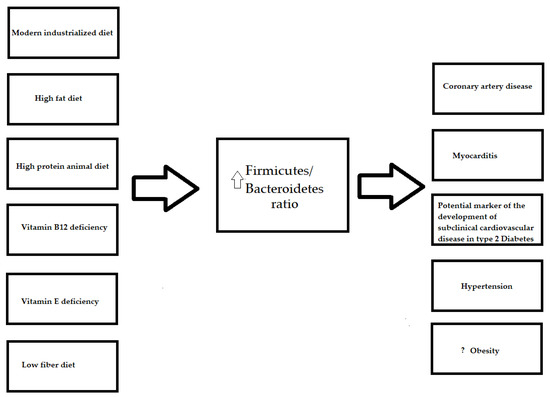

The gut microbiota of adults mainly consists of Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes that, together with Actinobacteria and Proteobacteria, account for nearly 99% of the intestinal microbiome [17]. It is worth noting that diet is suggested to be related to changes in all four of the main gut microbiome phyla (Table 1), although the authors paid particular attention to the abundance of Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes. The Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio is considered to be an indicator for gut dysbiosis. A higher ratio was found for an industrialized diet (Figure 1) [18], and was found to be associated with coronary artery disease [12,13][12][13] and myocarditis [19]. Furthermore, it was proven that fecal microbiota transplantation, a method that is used to restore gut homeostasis, alleviates myocardial damage in myocarditis [19].

Figure 1. The influence of the diet on Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio and diseases. ?

Table 1. The relation between diet pattern and gut microbiome composition.

| Pattern of the Diet | Increase in Microbiome | Decrease in Microbiome | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional diet |

|

| ||||

| Modern industrialized diet |

|

|

3. Diet Compound

3.1. Fats

The relationships between dietary fat and health are complex. On the one hand, diets high in saturated and trans fatty acids increase the risk of cardiovascular diseases via the up-regulation of total blood cholesterol and LDL-cholesterol [20]. On the other hand, mono- and polyunsaturated fats are beneficial to our health.

The contribution of the gut microbiome to fat metabolism is multidirectional. Gut microbiota (such as Eubacterium and Bacteroides) are proven to participate in the conversion of cholesterol to coprostanol, which is a non-absorbable sterol excreted in the feces. Two major pathways have been proposed for this process. The first involves a direct reduction in the 5–6 double bond in cholesterol, while the second consists of the oxidation of the 3β-hydroxy group and the isomerization of the double bond to yield 4-cholesten-3-one, which undergoes two reductions to form coprostanone and then coprostanol [21]. Furthermore, diets rich in fats stimulate the production of bile acids that, in addition to their role in the absorption of dietary lipids and lipid-soluble nutrients, exhibit antimicrobial activity and promote microbiome species capable of metabolizing bile acids in the intestine [21]. Microbiota also participates in the transformation of primary bile acid to secondary bile acid via the deconjugation, oxidation and epimerization of hydroxyl groups at C3, C7 and C12, 7-dehydroxylation, esterification and desulfatation [21]. Different secondary bile acids can influence health in various ways [21].

The human diet is important for the gut microbiome composition in both adult life and during childhood and even before birth. A study by Chu et al. revealed that, independent of maternal body mass index, a maternal high-fat diet is associated with distinct changes in the neonatal gut microbiome at birth, which persists through 4–6 weeks of age [22]. The study showed that a diet rich in fat caused a reduction in the Bacteroides species in the infant gut [22]. These microbes are responsible for the polysaccharide metabolism, including for the production of short-chain fatty acids from human milk oligosaccharides, which is a major energy source for rapidly growing infants [23] and affects their immune development [23]. Higher dietary fat content also resulted in an increase in Firmicutes, Proteobacteria and Actinobacteria in mice [24,25,26,27][24][25][26][27]. The data concerning Bacteroidetes in the context of a fat rich diet are ambiguous [24,26,28][24][26][28]. This might be related to the fact that, as shown by Wu et al., among Bacteroidetes, Bacteroides species are associated with long-term proteins and animal-fat consumption, whereas increased levels of Prevotella were found in patients with diets high in carbohydrates, especially fiber [29]. Furthermore, it was proven that a high-fat diet increased the abundance of Gram-negative bacteria [30].

Additionally, a meta-analysis based on 27 dietary studies, including 1,101 samples from rodents and humans in a finer taxonomic analysis, revealed that the most reproducible signals of a high-fat diet are Lactococcus species (Firmicutes), which were demonstrated to be common dietary contaminants [31]. Furthermore, in this study, the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio was significantly correlated with fat content [31] (Figure 1).

What Does It Mean for the Heart?

Gut microbiome changes, related to high-fat diets, are presented in Table 2. An increase in Lactococcus, which belong to Firmicutes phylum and participate in glucose fermentation and, therefore, lactic acid production, was shown to have both pathogenic and protective capabilities. It was demonstrated that milk fermented by Lactococcus lactis imparts an important systolic and diastolic blood pressure and HR-lowering effect [32].

Table 2. The relation between diet compound and gut microbiome composition.

| Pattern of the Diet | Increase in Microbiome | Decrease in Microbiome | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High fat diet |

|

| ||||

| High protein plant diet |

|

| ||||

| High protein animal diet |

|

| ||||

| Dietary protein amount: 100 to 200 g/kg |

|

| ||||

| Dietary protein amount: dose greater than 200 g/kg |

| |||||

| High carbohydrates diet |

|

| ||||

| High fiber diet |

|

| ||||

| Diet sufficient with vitamin D |

|

| ||||

| Diet sufficient with vitamin A |

| |||||

| Diet sufficient with vitamin B12 |

|

| ||||

| Diet sufficient with vitamin E |

|

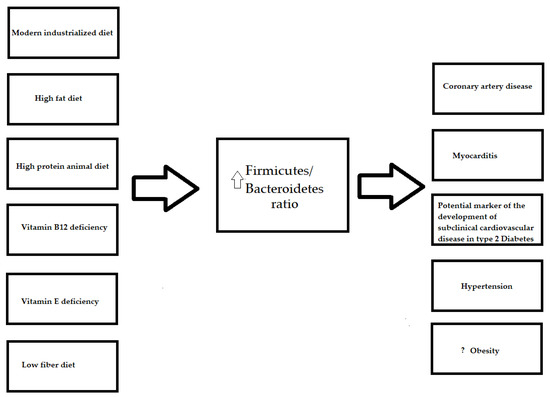

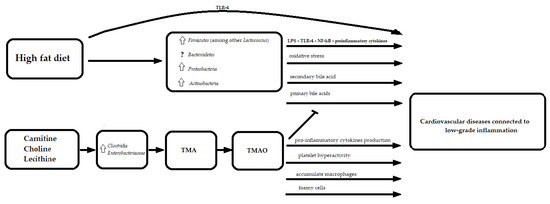

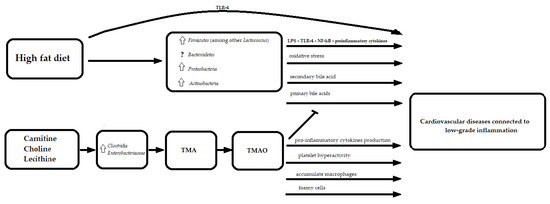

A high fat diet is suspected to play a role in chronic low-grade inflammation, which can cause atherosclerosis in many cardiovascular diseases. It has also been suggested to be related to an increased abundance of Gram-negative bacteria, which contain lipopolysaccharides on their outer membrane (LPS) [53]. The lipid A component of LPS binds to Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR-4) [53], leading to the activation of nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) signaling the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines [54]. TLR-4 may also be stimulated directly by free fatty acids [55]. In addition, high-fat diets increase barrier-disrupting cytokines (tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF α), interleukin (IL) 1B, IL6, and interferon γ) and decrease barrier-forming cytokines (IL10, IL17, and IL22) [56]. These mechanisms increase gut permeability and promote LPS, free fatty acids and the infiltration of pro-inflammatory cytokines into the circulation [57].

What is more, in a mice study, changes of the gut microbiota induced by a long-term high-fat diet were associated with increased intestinal oxidative stress expressed as reactive oxygen species, total antioxidant capacity, and malondialdehyde [58].

Furthermore, the previously mentioned bile acids are recognized as signaling molecules through the activation of receptors such as the farnesoid X receptor (FXR) or G protein-coupled receptor (TGR5) [59]. Moreover, the inhibition of bile acid synthesis in the liver might be regulated by the gut microbiota-dependent expression of fibroblast growth factor 15 in the ileum and cholesterol 7α-hydroxylase (CYP7A1) in the liver by FXR-dependent mechanisms [60]. In the literature, the tauro-conjugated beta- and alpha-muricholic acids were identified as FXR antagonists [60]. The activation of vasculature-specific FXR improves lipid profiles and influences vascular tension, thereby resulting in an anti-atherosclerotic effect [61]. On the other hand, FXR expression was significantly up-regulated in the ischemic cardiac tissue in rats, and the inhibition of FXR reduced the size of the insult, suggesting that FXR plays an important role in mediating cardiac apoptosis and injury [61] (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The molecular mechanisms linking fat in diet, gut microbiota and cardiovascular diseases. TMA—trimethylamine; TMAO—trimethylamine N-oxide; LPS—lipopolysaccharide; TLR-4—Toll-like receptor 4; NF-kB—Nuclear Factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells; ?

Furthermore, it was shown that trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) induces atherosclerosis by reducing cholesterol metabolism through hepatic bile acid inhibition [62].

TMAO is a product of trimethylamine (TMA) oxidation via hepatic flavin monooxygenases. TMA is produced by gut microbes, such as Clostridia and Enterobacteriaceae, from carnitine, choline, and lecithin, which can be found in various dietary products including red meat and eggs [63]. The proatherosclerosis function of TMAO might be related to two macrophage scavenger receptors (cluster of differentiation 36 and scavenger receptor A) leading to the accumulation of macrophages, foamy cells formation and the promotion of inflammation [64,65,66,67][64][65][66][67]. The CD36/MAPK/JNK pathway may play a crucial role in the formation of TMAO-induced foam cells [68]. TMAO can cause increased pro-inflammatory cytokines production, such as TNF α and IL-1B, while decreasing anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10 [69]. Moreover, TMAO was reported to induce platelet hyperactivity, which could lead to atherosclerotic thrombotic events [70]. Therefore, TMAO is considered to be one of pivotal mechanisms through which the diet and microbiome may affect the development of atherosclerosis (Figure 2).

3.2. Proteins

Dietary proteins are considered to be one of the most important macronutrients. They are digested to produce amino acids, which are used for protein synthesis. They have many important functions in the human body, including in the cardiovascular system, for instance, for transport (hemoglobin) and muscle contraction (actin, myosin). The undigested proteins and amino acids are mainly fermented by bacteria into various metabolites, such as organic amines, hydrogen sulfate and ammonia, both of which participate in various physiological functions related to host health and diseases. Greater levels of undigested proteins lead to an increase in pathogenic microorganism with an associated higher risk of metabolic diseases [71]. Both the origin of the protein (animal vs. plant) and its concentration can influence the gut microbiome [71]. It was shown that a diet enriched with 20% peanut protein led to an increase in Bifidobacterium and a reduction in Enterobacteria and Clostridium perfringensa in rats [33]. Furthermore, a higher intake of soybean protein was associated with an increase in Escherichia and Propionibacterium abundance [34[34][35][36],35,36], whereas data from the literature revealed that casein, a protein present in milk, can also increase the abundance of Bifidobacterium and Lactobacilli [37], and decrease the abundance of Staphylococci, Coliformis, Streptococci [38], Eubacterium rectale and Marvinbryantia formatexigens [39]. Moreover, in the study of Garcia-Mantrana I. et al. a higher intake of animal protein was found to be related to a significantly lower presence of Bacteroidetes (p = 0.029) and a higher Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio [15].

Moreover, a randomized, double-blind, parallel-design trial conducted in 38 overweight individuals, who received high-protein isocaloric diets with casein, soy protein or a maltodextrin (control) supplementation, revealed that high-protein diets did not alter the microbiota composition, but induced a shift in bacterial metabolism toward amino acid degradation with different metabolite profiles in accordance with the protein source [72]. Another study suggests that the dietary protein/fat ratio has only minimal, transient effects on the gut microbiota composition; however, gut microbiota might contribute to variability in host responses to high altitude [73]. Moreover, a positive correlation was found between Firmicutes abundance and high concentrations of amino acid degradation products, that might be related to Clostridia activity [74] and a negative correlation was identified for an abundance of Bacteroidetes with the exception for Butyricimonas and Odoribacter genera, both of which showed a positive correlation [72]. A low amount of protein in the diet, by reducing substrate for pathogenic bacteria proliferation, resulted in reduced Escherichia coli abundance on the mucosal surface [75,76,77][75][76][77]. The gut microbiome composition in animal models seems to be strictly associated with the consumption of dietary protein, whereby doses from 100 to 200 g/kg caused an increase in Lactobacilli and a reduction in Coliformis and Staphylococci; doses greater than 200 g/kg caused an increase in Coliforms, Streptococcus and Bacillus [40].

The above-mentioned studies confirm proteins’ role in regulating the gut microbiome; however, the study based on 109 healthy men and women aged 21 to 65, with a body mass index of 18 to 36, revealed that protein is less influential than saturated fat [78].

What Does It Mean for the Heart?

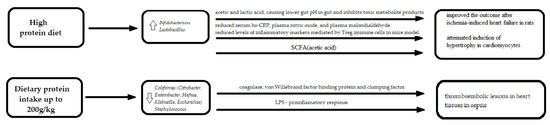

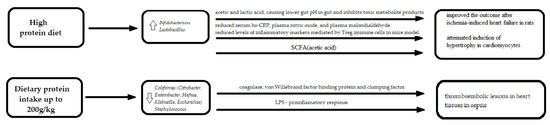

Both the type and the amount of proteins in the diet seem to play a role in gut microbiome composition, which influences our health and, more specifically, the heart (Table 2).

Diets rich with plants as well as animal protein were associated with an increase of some genus of Firmucutes and Actinobacteria, particularly with a high abundance of Bifidobacterium, which, together with Lactobacilli, are used as probiotics. Increased Bifidobacterium contributes to the generation of more microbial metabolites, including acetic acid and lactic acid, resulting in a lower pH in the gut, that inhibits toxic metabolite products, such as amine and benzpyrole. Its increased abundance was shown in heart failure patients [79], while its protective role in myocardium infarction was proven in mice models [80]. Pretreatment with Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis 420 for 10 or 28 days attenuated cardiac injury from ischemia-reperfusion and reduced levels of inflammatory markers, which was mediated by Treg immune cells in mice models [80]. Furthermore, the symbiotic supplementation of Lactobacillus acidophilus, Lactobacillus casei, and Bifidobacterium bifidum for 12 weeks among people who are overweight, or have diabetes and coronary heart disease had beneficial effects on serum hs-CRP, plasma nitric oxide, and plasma malondialdehyde levels [81]. The supplementation did not have any effect on other biomarkers of oxidative stress levels and on carotid intima-media thickness [81]. Unfortunately, in this study, gut microbiome composition was not investigated. The oral supplementation of Lactobacillus rhamnosus significantly improved outcomes following ischemia-induced heart failure in rats [82] and attenuated the induction of hypertrophy in cardiomyocytes [83].

In an animal model, a dietary intake of protein of up to 200 g/kg was related to changes in the gut microbiome through a reduction of pathogenic bacteria Coliformis (Citrobacter, Enterobacter, Hafnia, Klebsiella, Escherichia) and Staphylococci, whereas an increase in protein intake was related to an increase in the abundance of those bacteria [61]. These Gram-negative bacteria affect homeostasis through LPS production. Furthermore, some of these bacteria (Klebsiella and Streptococcus) were found in atherosclerotic lesions [84]. In mice models, three secreted products, namely, staphylococci–coagulase, the von Willebrand factor binding protein and the clumping factor were proven to promote thromboembolic lesions in heart tissues in sepsis [85]. The first two are known to activate prothrombin to cleave fibrinogen, while clumping factor allowed Staphylococci to associate with the resulting fibrin [85].

Interestingly, high concentrations of the amino acid degradation products were correlated directly with two genera from the Odoribacteraceae family, which seem to have different relationships with blood pressure [72]. On the one hand, they were positively related to Butyricimonas, which was shown to have a positive correlation with mean arterial pressure in elderly women from South Korea [86]. On the other hand, Odoribacter, a short-chain fatty acid-producing bacteria, was proven to help maintain lower systolic blood pressure in pregnant women through butyrate production [87], and in rats [88]. Despite the positive role of Odoribacter in controlling blood pressure, it was directly correlated with aortic aneurysm diameters in mice [89] (Figure 3).

Figure 3. The molecular mechanisms linking protein in diet, gut microbiota and cardiovascular diseases. LPS—lipopolysaccharide; SCFA—Short-Chain Fatty Acid; CRP—c-reactive protein;

3.3. Carbohydrates

Daily energy requirements depend on gender, age, height, weight, health, and levels of physical activity. In both the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular diseases, maintaining a particular body weight is extremely important. Carbohydrates, as the main source of energy in the diet, are crucial for energy homeostasis.

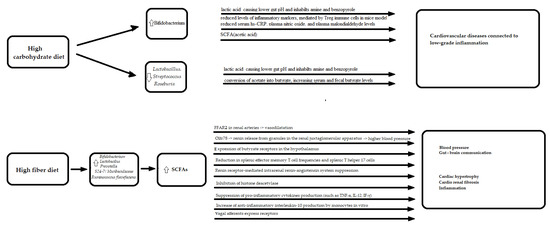

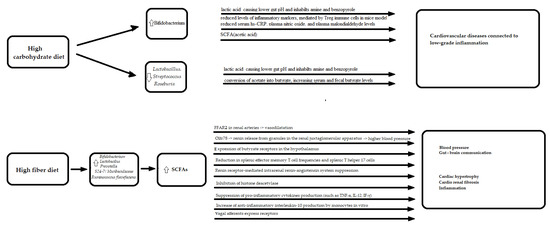

Feva et al. studied 88 subjects at an increased risk of metabolic syndrome, who were kept on a high saturated fat diet for 4 weeks (baseline), and were then randomly placed under one of the five experimental diets for 24 weeks [41]. The study revealed that low fat, high carbohydrate diets increased fecal Bifidobacterium and high carbohydrate/high glycemic index increased fecal Bacteroides, whereas high carbohydrate/low glycemic index and a high saturated diet increased Faecalibacterium prausnitzii. Changes in the abundance of fecal Bacteroides correlated inversely with body weight [41]. Another study showed that supplementing the diet with galacto-oligosaccharides increased the abundance of Bifidobacterium species in feces five-fold in obese or overweight people [42].

Furthermore, an analysis conducted on 1135 participants from a Dutch population, using deep sequencing [43], showed that a higher intake of total carbohydrates were most strongly associated with an increase in Bifidobacteria, while they were associated with a decrease in Lactobacillus, Streptococcus, and Roseburia [43]. Lactobacillus and Streptococcus are lactose-fermenting bacteria that, through lactic acid production, lower the gut pH and inhibits amine and benzopyrole production, while Roseburia lead to increasing serum and fecal butyrate levels via the conversion of acetate into butyrate [90].

3.3.1. Dietary Fiber

Fiber contains a mixture of polysaccharide and non-polysaccharide substances (such as lignins, cutins) that cannot be digested by enzymes of the human digestive tract. Instead, it is metabolized by microbes that generate short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), including acetate, propionate and butyrate. Most of the produced acetate and propionate is absorbed by the gut, while butyrate is used by colon mucosa cells as a primary energy source [91].

The effects of fiber in the gut microbiome were summarized in a systematic review and meta-analysis from 2018, which was based on a total of 64 studies involving 2099 participants [44]. Dietary fiber intervention resulted in a higher abundance of Bifidobacterium spp., Lactobacillus [44,47][44][47] and the fecal butyrate concentration [44]. Moreover, a subgroup analysis revealed that fructans and galactooligosaccharides also led to a significantly greater abundance of the same bacteria [47]. Another study based on whole-genome shotgun sequencing revealed that fiber consumption shifted the Bacteroidetes/Firmicutes ratio, increasing the relative abundance of Bacteroidetes [62]. Furthermore, an analysis of correlations showed a positive relation between the Bacteroidetes/Firmicutes ratio and total dietary fiber intake but not with body mass index [47].

Notably, in mice studies, diets with navy bean and black bean flours rich in non-digestible fermentable carbohydrates increased the abundance of carbohydrate fermenting bacteria such as Prevotella, S24-7 and Ruminococcus flavefaciens, which coincided with enhanced short-chain fatty acid production and colonic expression of the SCFA receptors GPR-41/-43/-109a [46].

3.3.2. What Does It Mean for the Heart?

Similarly to a high-protein diet, high-carbohydrate and high-fiber diets resulted in an increase in the genus Bifidobacterium from phylum Actinobacteria, that imparts positive effects on health and the heart was previously discussed. Furthermore, a high-carbohydrate and high-fiber diet was also related to an increase in Bacteroidetes, which caused a decrease in Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio. As mentioned previously, a higher Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio was related to an industrialized diet and many cardiovascular diseases [12,13,19][12][13][19]. A particular genus, Prevotella, from the phylum Bacteroidetes, associated with a diet rich in non-digestible carbohydrates, seems to also have a negative influence on health despite its positive value. It also plays an important role in dysbiosis in pre- and hypertension patients [92]. This genus was increase in high lifetime cardiovascular disease risk profile Bogalusa Heart Study participants [93] and Prevotella copri was proven to be associated with cardiac valve calcification [94].

Furthermore, after a high-fiber diet, a higher abundance of SCFAs intestinal producers was revealed. SCFAs (acetate, propionate and butyrate) are generally considered as favorable to health and their role was described in cardiovascular pathologies, including in hypertension [95,96][95][96] and atherosclerosis [95]. Interestingly, despite the fact that SCFA-producing bacteria were associated with lower blood pressure [97[97][98],98], the SCFAs concentration of stool was associated with higher blood pressure [97,98,99][97][98][99]. In order to elucidate this issue, studies concerning both the fecal and serum measurement of SCFAs should be included in future research.

Animal models suggest that SCFAs act via fatty acid receptors FFAR2 (GPR43), FFAR3 (GPR41) [100], olfactory receptor 78 (the human analogue-OR51E2) [101] and GPR109A (hydroxycarboxylic acid receptor (HCA) 2) [102]. The expression of these receptors differs between tissues and cell types, and it is present in intestinal epithelial cells, immune cells, and adipocytes. Propionate was proven to be the most potent agonist for both FFAR3 and FFAR2. Acetate was more selective for FFAR2, whereas butyrate and isobutyrate were more active on FFAR3 [100]. FFAR2 expressed in the renal arteries causes vasodilatation in response to SCFAs, whereas Olfr78 mediated higher blood pressure through rennin release from granules in the renal juxtaglomerular apparatus [103]. The potency of SCFAs is much lower for Olfr78 and OR51E2, than for FFAR2, and therefore, it was suggested that Olfr78 serves as a negative feedback loop for the blood pressure, reducing the effects of FFAR2 [101]. Furthermore, propionate, in the absence of one of two SCFAs sensory receptors (Olfr78 and FFAR3), differentially modulated blood pressure [104]. SCFAs have also been suggested to be implicated in gut–brain communication, via the expression of butyrate receptors in the hypothalamus [105] and vagal afferents express receptors [106].

Furthermore, a study of mice models with transcriptome analyses showed that the protective effects of a high-fiber diet and acetate supplementation were accompanied by the down-regulation of cardiac and renal Egr1, which is involved in cardiac hypertrophy, cardio renal fibrosis, and inflammation [107]. Furthermore, a recently published article confirms fiber’s role in blood pressure reduction that it is associated with sympatholytic negative inotropic effects, in vivo [108].

Propionate supplementation in mice models resulted in attenuated cardiac hypertrophy, fibrosis, vascular dysfunction and hypertension [109]. This effect was related to reduced systemic inflammation, which is defined as a reduction in splenic effector memory T cell frequencies and splenic T helper 17 cells [109].

The antihypertensive effect of sodium butyrate supplementation in rat models was related to (pro) renin receptor-mediated intrarenal renin-angiotensin system suppression [110] as well as anti-inflammatory effects that are presumed to be mediated by the inhibition of histone deacetylase [110]. Butyrate suppresses the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as tumor-necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-12 (IL-12), and interferon-γ (IF-γ), and up-regulates the production of anti-inflammatory interleukin-10 (IL-10) by monocytes, in vitro [110] (Figure 4).

Figure 4. The molecular mechanisms linking carbohydrate in diet, gut microbiota and cardiovascular diseases. LPS—lipopolysaccharide; SCFA—Short-Chain Fatty Acid; CRP—c-reactive protein; FFAR2—Free fatty acid receptor 2; Olfr 78—olfactory receptor 78; TNF—Tumor necrosis factor, IL—interleukin;

3.4. Vitamins

Data concerning vitamins, the gut microbiome and cardiovascular diseases combined are limited in the literature. Among vitamins, vitamin D is the most widely described in the literature in this context. Although vitamin D has been traditionally recognized as a vitamin responsible for bone–mineral health, its role in hypertension, peripheral artery disease, myocardial infarction and heart failure has also been described [111].

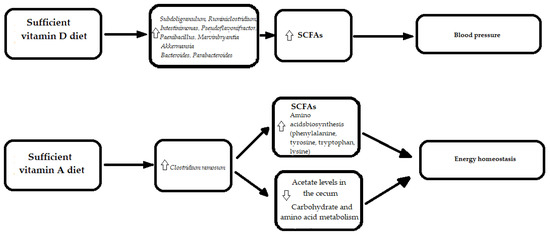

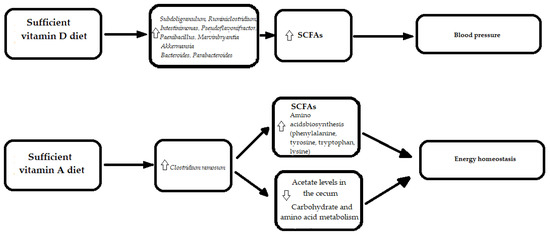

In a cohort of 34 hypertension patients and 15 healthy controls, Zuo et al. suggested that gut microbiome dysbiosis, contributing to the hypertension development, might be partially mediated by vitamin D3 deficiency [112]. Vitamin D3 was significantly decreased in the feces of hypertension patients and correlated with decreased biodiversity, expressed through the Shannon index and Pielou evenness [112]. Moreover, fecal vitamin D3 positively correlated with Subdoligranulum, Ruminiclostridium, Intestinimonas, Pseudoflavonifractor, Paenibacillus, and Marvinbryantia genera from Firmicutes [112]. A recently published article on vitamin D and gut the microbiome includes a study of 567 older men, and identified eight taxa in the Firmicutes phylum that were positively associated with vitamin D metabolites. In the study, men with higher levels of calcitriol and higher calcitriol activation ratios, but not calcifediol, were more likely to possess butyrate-producing bacteria that are associated with better gut microbial health [48] and clinical status.

A recent human study on twenty adults with vitamin D insufficiency or deficiency, who were given 600, 4000 or 10,000 IU/day of oral vitamin D3, revealed that a higher baseline vitamin D concentration was associated with an increased relative abundance of Akkermansia (phylum Verrucomicrobia) and a decreased relative abundance of Porphyromonas (phylum Bacteroidetes), whereas after the intervention, dose-dependent increases in the relative abundance of Bacteroides (phylum Bacteroidetes) and Parabacteroides (phylum Bacteroidetes) were found [113].

For vitamin A, a relationship with formation of congenital heart defects [49], and energy homeostasis [114] were revealed. A study concerning vitamin A and the gut microbiome in mice models showed that mice with a vitamin A-deficient diet had significantly lower butyrate levels and higher acetate levels in the cecum compared to mice with a vitamin A-sufficient diet. The increase in butyrate levels in mice with a vitamin A-sufficient diet corresponded to higher numbers of the butyrate-producing bacteria—Clostridium ramosum (a member of Clostridium_XVIII), than for mice with a vitamin A-deficient diet. Mice with a vitamin A-deficient diet demonstrated disturbances in multiple metabolic pathways, including alterations in energy homeostasis [114]. Furthermore, a PICRUSt analysis revealed that bacteria from vitamin A-sufficient mice resulted in the enrichment of genes that are important in the biosynthesis of some amino acids, including phenylalanine, tyrosine, tryptophan, and lysine, while bacterial communities from vitamin A-insufficient mice had an enhanced carbohydrate and amino acid metabolism [114] (Figure 5).

Figure 5. The molecular mechanisms linking vitamins in diet, gut microbiota and cardiovascular diseases. SCFAs—Short-Chain Fatty Acids.

Moreover, studies on vitamin B12 indicated that supplementation with cobalamin and whey increased Bacteroidetes/Firmicutes ratio and reduced Proteobacteria spp. abundance (Escherichia/Shigella spp. and Pseudomonas) [50]. In the study, cobalamin was found to enhance the growth of Bacteroidetes; meanwhile whey protein promoted the growth of Firmicutes [50].

In mice models, the low-vitamin E group was characterized with higher Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio [51]. Furthermore, contrary to the control group, in the low- and high-vitamin E groups, Escherichia coli was found to be present [51].

What Does It Mean for the Heart?

The most widely described association in the literature is between fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, and K) and the gut microbiome. The above-mentioned data suggest that a higher concentration of vitamin D resulted in an increase in genera from Firmicutes phylum, which are responsible for lactic acid and butyrate production and are, therefore, supportive to our health. Furthermore, vitamin D concentrations were positively associated with an increased relative abundance of Akkermansia (phylum Verrucomicrobia), which was proven to be a beneficial microbe in terms of obesity, glucose and lipid metabolism [52]. In humans with a high body weight, blood cholesterol and fasting blood glucose level, the abundance of Akkermansia in the gut was lower than in healthy individuals [115]. Moreover, in mouse models, the high level of blood lipopolysaccharide, an indicator of intestinal permeability, decreased with the administration of Akkermansia [116].

Vitamin E and B12 deficiencies, lead to an increased Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio, which has been described in many cardiovascular diseases (Figure 1).

3.5. Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes Ratio and Diet

Despite findings, with regard to the profiles of particular microorganisms in relation to diet, differing between studies, the most common result is the change in the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio. The Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio, which is considered to be an indicator for gut dysbiosis, seems to increase in an unhealthy diet pattern, such as the modern industrialized diet, which includes a high amount of fat, animal protein and a lack of vitamin B12 and E (Figure 1). A higher Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio is related to many inflammatory and metabolic disorders, including cardiovascular pathologies [12,13,19,117,118,119,120,121][12][13][19][117][118][119][120][121]. Although, in general, results of the intervention and observational studies confirm Bacteroidetes decrease and Firmicutes increase in obese humans [122] and animals [123], a meta-analysis performed by Sze M.C. et al. did not confirm such an association [124]. Therefore, further interventional studies across a large population are required to elucidate the relationship between the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio and obesity.

References

- National HES Manual. Available online: http://www.ehes.info/manuals/national_manuals/national_manual_Poland_PL.pdf (accessed on 3 September 2021).

- Stokes, J., 3rd; Kannel, W.B.; Dawber, T.R.; Kagan, A.; Revotskie, N. Factors of risk in the development of coronary heart disease-six year follow-up experience. The Framingham Study. Ann. Intern. Med. 1961, 55, 33–50.

- Townsend, N.; Wilson, L.; Bhatnagar, P.; Wickramasinghe, K.; Rayner, M.; Nichols, M. Cardiovascular disease in Europe: Epidemiological update 2016. Eur. Heart J. 2016, 37, 3232–3245.

- Bäckhed, F.; Ley, R.E.; Sonnenburg, J.L.; Peterson, D.A.; Gordon, J.I. Host-bacterial mutualism in the human intestine. Science 2005, 307, 1915–1920.

- Xu, J.; Gordon, J.I. Honor thy symbionts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 10452–10459.

- Chow, J.; Lee, S.M.; Shen, Y.; Khosravi, A.; Mazmanian, S.K. Host-bacterial symbiosis in health and disease. Adv. Immunol. 2010, 107, 243–274.

- Witkowski, M.; Weeks, T.L.; Hazen, S.L. Gut Microbiota and Cardiovascular Disease. Circ. Res. 2020, 127, 553–570.

- Stewart, C.J.; Ajami, N.J.; O’Brien, J.L.; Hutchinson, D.S.; Smith, D.P.; Wong, M.C.; Ross, M.C.; Lloyd, R.E.; Doddapaneni, H.; Metcalf, G.A.; et al. Temporal development of the gut microbiome in early childhood from the TEDDY study. Nature 2018, 562, 583–588.

- Rodríguez, J.M.; Murphy, K.; Stanton, C.; Ross, R.P.; Kober, O.I.; Juge, N.; Avershina, E.; Rudi, K.; Narbad, A.; Jenmalm, M.C.; et al. The composition of the gut microbiota throughout life, with an emphasis on early life. Microb. Ecol. Health Dis. 2015, 26, 26050.

- De Filippo, C.; Cavalieri, D.; Di Paola, M.; Ramazzotti, M.; Poullet, J.B.; Massart, S.; Collini, S.; Pieraccini, G.; Lionetti, P. Impact of diet in shaping gut microbiota revealed by a comparative study in children from Europe and rural Africa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 14691–14696.

- Turroni, S.; Fiori, J.; Rampelli, S.; Schnorr, S.L.; Consolandi, C.; Barone, M.; Biagi, E.; Fanelli, F.; Mezzullo, M.; Crittenden, A.N.; et al. Fecal metabolome of the Hadza hunter-gatherers: A host-microbiome integrative view. Sci. Rep. 2016, 14, 32826.

- Emoto, T.; Yamashita, T.; Sasaki, N.; Hirota, Y.; Hayashi, T.; So, A.; Kasahara, K.; Yodoi, K.; Matsumoto, T.; Mizoguchi, T.; et al. Analysis of gut microbiota in coronary artery disease patients: A possible link between gut microbiota and coronary artery disease. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2016, 23, 908–921.

- Liu, L.; He, X.; Feng, Y. Coronary heart disease and intestinal microbiota. Coron. Artery Dis. 2019, 30, 384–389.

- García-Montero, C.; Fraile-Martínez, O.; Gómez-Lahoz, A.M.; Pekarek, L.; Castellanos, A.J.; Noguerales-Fraguas, F.; Coca, S.; Guijarro, L.G.; García-Honduvilla, N.; Asúnsolo, A.; et al. Nutritional Components in Western Diet Versus Mediterranean Diet at the Gut Microbiota-Immune System Interplay. Implications for Health and Disease. Nutrients 2021, 13, 699.

- Garcia-Mantrana, I.; Selma-Royo, M.; Alcantara, C.; Collado, M.C. Shifts on gut microbiota associated to mediterranean diet adherence and specific dietary intakes on general adult population. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 890.

- Merra, G.; Noce, A.; Marrone, G.; Cintoni, M.; Tarsitano, M.G.; Capacci, A.; De Lorenzo, A. Influence of mediterranean diet on human gut microbiota. Nutrients 2021, 13, 7.

- Yamashita, T.; Emoto, T.; Sasaki, N.; Hirata, K.I. Gut microbiota and coronary artery disease. Int. Heart J. 2016, 57, 663–671.

- Lin, A.; Bik, E.M.; Costello, E.K.; Dethlefsen, L.; Haque, R.; Relman, D.A.; Singh, A. Distinct distal gut microbiome diversity and composition in healthy children from Bangladesh and the United States. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e53838.

- Hu, X.F.; Zhang, W.Y.; Wen, Q.; Chen, W.J.; Wang, Z.M.; Chen, J.; Zhu, F.; Liu, K.; Cheng, L.X.; Yang, J.; et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation alleviates myocardial damage in myocarditis by restoring the microbiota composition. Pharmacol. Res. 2019, 139, 412–421.

- Spady, D.K.; Woollett, L.A.; Dietschy, J.M. Regulation of plasma LDL cholesterol levels by dietary cholesterol and fatty acids. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 1993, 13, 355–381.

- Gerard, P. Metabolism of cholesterol and bile acids by the gut microbiota. Pathogens 2014, 3, 14–24.

- Alou, M.T.; Lagier, J.C.; Raoult, D. Diet influence on the gut microbiota and dysbiosis related to nutritional disorders. Hum. Microb. J. 2016, 1, 3–11.

- Salyers, A.A.; West, S.E.; Vercellotti, J.R.; Wilkins, T.D. Fermentation of mucins and plant polysaccharides by anaerobic bacteria from the human colon. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1977, 34, 529–533.

- Hildebrandt, M.A.; Hoffmann, C.; Sherrill-Mix, S.A.; Keilbaugh, S.A.; Hamady, M.; Chen, Y.Y.; Knight, R.; Ahima, R.S.; Bushman, F.; Wu, G.D. High-fat diet determines the composition of the murine gut microbiome independently of obesity. Gastroenterology 2009, 137, 1716–1724.

- Shang, Y.; Khafipour, E.; Derakhshani, H.; Sarna, L.K.; Woo, C.W.; Siow, Y.L.; Karmin, O. Short term high fat diet induces obesity enhancing changes in mouse gut microbiota that are partially reversed by cessation of the high fat diet. Lipids 2017, 52, 499–511.

- Hamilton, M.K.; Boudry, G.; Lemay, D.G.; Raybould, H.E. Changes in intestinal barrier function and gut microbiota in high-fat diet-fed rats are dynamic and region dependent. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2015, 308, 840–851.

- De Wit, N.; Derrien, M.; Bosch-Vermeulen, H.; Oosterink, E.; Keshtkar, S.; Duval, C.; de Vogel-van den Bosch, J.; Kleerebezem, M.; Müller, M.; van der Meer, R. Saturated fat stimulates obesity and hepatic steatosis and affects gut microbiota composition by an enhanced overflow of dietary fat to the distal intestine. AJP Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2012, 303, 589–599.

- Wu, G.D.; Chen, J.; Hoffmann, C.; Bittinger, K.; Chen, Y.Y.; Keilbaugh, S.A.; Bewtra, M.; Knights, D.; Walters, W.A.; Knight, R.; et al. Linking Long-term dietary patterns with gut microbial enterotypes. Science 2011, 334, 105–108.

- Arumugam, M.; Raes, J.; Pelletier, E.; Le Paslier, D.; Yamada, T.; Mende, D.R.; Fernandes, G.R.; Tap, J.; Bruls, T.; Batto, J.M.; et al. Enterotypes of the human gut microbiome. Nature 2011, 473, 174–180.

- Cani, P.D.; Amar, J.; Iglesias, M.A.; Poggi, M.; Knauf, C.; Bastelica, D.; Neyrinck, A.M.; Fava, F.; Tuohy, K.M.; Chabo, C.; et al. Metabolic endotoxemia initiates obesity and insulin resistance. Diabetes 2007, 56, 1761–1772.

- Bisanz, J.E.; Upadhyay, V.; Turnbaugh, J.A.; Ly, K.; Turnbaugh, P.J. Meta-Analysis Reveals Reproducible Gut Microbiome Alterations in Response to a High-Fat Diet. Cell Host Microbe 2019, 26, 265–272.

- Rodríguez-Figueroa, J.C.; González-Córdova, A.F.; Astiazaran-García, H.; Vallejo-Cordoba, B. Hypotensive and heart rate-lowering effects in rats receiving milk fermented by specific Lactococcus lactis strains. Br. J. Nutr. 2013, 109, 827–833.

- Peng, M.; Bitsko, E.; Biswas, D. Functional properties of peanut fractions on the growth of probiotics and foodborne bacterial pathogens. J. Food Sci. 2015, 80, 635–641.

- Lozupone, C.A.; Stombaugh, J.I.; Gordon, J.I.; Jansson, J.K.; Knight, R. Diversity, stability and resilience of the human gut microbiota. Nature 2012, 489, 220–230.

- Tremaroli, V.; Bäckhed, F. Functional interactions between the gut microbiota and host metabolism. Nature 2012, 489, 242–249.

- Deplancke, B.; Gaskins, H.R. Microbial modulation of innate defense: Goblet cells and the intestinal mucus layer. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2001, 73, 1131–1141.

- Hancock, R.E.; Haney, E.F.; Gill, E.E. The immunology of host defence peptides: Beyond antimicrobial activity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2016, 16, 321–334.

- Hooper, L.V.; Littman, D.R.; Macpherson, A.J. Interactions between the microbiota and the immune system. Science 2012, 336, 1268–1273.

- Faith, J.J.; McNulty, N.P.; Rey, F.E.; Gordon, J.I. Predicting a human gut microbiota’s response to diet in gnotobiotic mice. Science 2011, 333, 101–104.

- Windey, K.; De Preter, V.; Verbeke, K. Relevance of protein fermentation to gut health. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2012, 56, 184–196.

- Fava, F.; Gitau, R.; Griffin, B.A.; Gibson, G.R.; Tuohy, K.M.; Lovegrove, J.A. The type and quantity of dietary fat and carbohydrate alter faecal microbiome and short-chain fatty acid excretion in a metabolic syndrome ‘at-risk’ population. Int. J. Obes. 2013, 37, 216–223.

- Canfora, E.E.; van der Beek, C.M.; Hermes, G.D.A.; Goossens, G.H.; Jocken, J.W.E.; Holst, J.J.; van Eijk, H.M.; Venema, K.; Smidt, H.; Zoetendal, E.G.; et al. Supplementation of Diet with Galacto-oligosaccharides Increases Bifidobacteria, but Not Insulin Sensitivity, in Obese Prediabetic Individuals. Gastroenterology 2017, 153, 87–97.

- Zhernakova, A.; Kurilshikov, A.; Bonder, M.J.; Tigchelaar, E.F.; Schirmer, M.; Vatanen, T.; Mujagic, Z.; Vila, A.V.; Falony, G.; Vieira-Silva, S.; et al. Population-based metagenomics analysis reveals markers for gut microbiome composition and diversity. Science 2016, 352, 565–569.

- So, D.; Whelan, K.; Rossi, M.; Morrison, M.; Holtmann, G.; Kelly, J.T.; Shanahan, E.R.; Staudacher, H.M.; Campbell, K.L. Dietary fiber intervention on gut microbiota composition in healthy adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 107, 965–983.

- Massot-Cladera, M.; Azagra-Boronat, I.; Franch, A.; Castell, M.; J Rodríguez-Lagunas, M.; Pérez-Cano, F.J. Gut Health-Promoting Benefits of a Dietary Supplement of Vitamins with Inulin and Acacia Fibers in Rats. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2196.

- Holscher, H.D.; Caporaso, J.G.; Hooda, S.; Brulc, J.M.; Fahey, G.C., Jr.; Swanson, K.S. Fiber supplementation influences phylogenetic structure and functional capacity of the human intestinal microbiome: Follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 101, 55–64.

- Monk, J.M.; Lepp, D.; Wu, W.; Pauls, K.P.; Robinson, L.E.; Power, K.A. Navy and black bean supplementation primes the colonic mucosal microenvironment to improve gut health. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2017, 49, 89–100.

- Thomas, R.L.; Jiang, L.; Adams, J.S.; Xu, Z.Z.; Shen, J.; Janssen, S.; Ackermann, G.; Vanderschueren, D.; Pauwels, S.; Knight, R.; et al. Vitamin D metabolites and the gut microbiome in older men. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5997.

- Sinning, A.R. Role of vitamin A in the formation of congenital heart defects. Anat. Rec. 1998, 253, 147–153.

- Wang, H.; Shou, Y.; Zhu, X.; Xu, Y.; Shi, L.; Xiang, S.; Feng, X.; Han, J. Stability of vitamin B12 with the protection of whey proteins and their effects on the gut microbiome. Food Chem. 2019, 276, 298–306.

- Choi, Y.; Lee, S.; Kim, S.; Lee, J.; Ha, J.; Oh, H.; Lee, Y.; Kim, Y.; Yoon, Y. Vitamin E (α-tocopherol) consumption influences gut microbiota composition. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 71, 221–225.

- Naito, Y.; Uchiyama, K.; Takagi, T. A next-generation beneficial microbe: Akkermansia muciniphila. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr. 2018, 63, 33–35.

- Raetz, C.R.H.; Whitfield, C. Lipopolysaccharide Endotoxins. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2002, 71, 635–700.

- Pålsson-McDermott, E.M.; O’Neill, L.A.J. Signal transduction by the lipopolysaccharide receptor, Toll-like receptor-4. Immunology 2004, 113, 153–162.

- Shi, H.; Kokoeva, M.V.; Inouye, K.; Tzameli, I.; Yin, H.; Flier, J.S. TLR4 links innate immunity and fatty acid-induced insulin resistance. J. Clin. Investig. 2006, 116, 3015–3025.

- Rohr, M.W.; Narasimhulu, C.A.; Rudeski-Rohr, T.A.; Parthasarathy, S. Negative Effects of a High-Fat Diet on Intestinal Permeability: A Review. Adv. Nutr. 2019, 11, 77–91.

- Bojková, B.; Winklewski, P.J.; Wszedybyl-Winklewska, M. Dietary Fat and Cancer-Which Is Good, Which Is Bad, and the Body of Evidence. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4114.

- Qiao, Y.; Sun, J.; Ding, Y.; Le, G.; Shi, Y. Alterations of the gut microbiota in high-fat diet mice is strongly linked to oxidative stress. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013, 97, 1689–1697.

- Hylemon, P.B.; Zhou, H.; Pandak, W.M.; Ren, S.; Gil, G.; Dent, P. Bile acids as regulatory molecules. J. Lipid Res. 2009, 50, 1509–1520.

- Sayin, S.I.; Wahlström, A.; Felin, J.; Jäntti, S.; Marschall, H.U.; Bamberg, K.; Angelin, B.; Hyötyläinen, T.; Orešič, M.; Bäckhed, F. Gut microbiota regulates bile acid metabolism by reducing the levels of tauro-beta-muricholic acid, a naturally occurring FXR antagonist. Cell Metab. 2013, 17, 225–235.

- Vasavan, T.; Ferraro, E.; Ibrahim, E.; Dixon, P.; Gorelik, J.; Williamson, C. Heart and bile acids—Clinical consequences of altered bile acid metabolism. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2018, 1864, 1345–1355.

- Chen, M.L.; Yi, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, X.; Ran, L.; Yang, J.; Zhu, J.D.; Zhang, Q.Y.; Mi, M.T. Resveratrol Attenuates Trimethylamine-N-Oxide (TMAO)-Induced Atherosclerosis by Regulating TMAO Synthesis and Bile Acid Metabolism via Remodeling of the Gut Microbiota. mBio 2016, 7, e02210-15.

- Rath, S.; Heidrich, B.; Pieper, D.H.; Vital, M. Uncovering the trimethylamine-producing bacteria of the human gut microbiota. Microbiome 2017, 5, 54.

- Wang, Z.; Klipfell, E.; Bennett, B.J.; Koeth, R.; Levison, B.S.; Dugar, B.; Feldstein, A.E.; Britt, E.B.; Fu, X.; Chung, Y.; et al. Gut flora metabolism of phosphatidylcholine promotes cardiovascular disease. Nature 2011, 472, 57–63.

- Koeth, R.A.; Wang, Z.; Levison, B.S.; Buffa, J.A.; Org, E.; Sheehy, B.T.; Britt, E.B.; Fu, X.; Wu, Y.; Li, L.; et al. Intestinal microbiota metabolism of L-carnitine, a nutrient in red meat, promotes atherosclerosis. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 576–585.

- Suzuki, H.; Kurihara, Y.; Takeya, M.; Kamada, N.; Kataoka, M.; Jishage, K.; Ueda, O.; Sakaguchi, H.; Higashi, T.; Suzuki, T.; et al. A role for macrophage scavenger receptors in atherosclerosis and susceptibility to infection. Nature 1997, 386, 292–296.

- Hardin, S.J.; Singh, M.; Eyob, W.; Molnar, J.C.; Homme, R.P.; George, A.K.; Tyagi, S.C. Diet-induced chronic syndrome, metabolically transformed trimethylamine-N-oxide, and the cardiovascular functions. Rev. Cardiovasc. Med. 2019, 20, 121–128.

- Geng, J.; Yang, C.; Wang, B.; Zhang, X.; Hu, T.; Gu, Y.; Li, J. Trimethylamine N-oxide promotes atherosclerosis via CD36-dependent MAPK/JNK pathway. E Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 97, 941–947.

- Yang, S.; Li, X.; Yang, F.; Zhao, R.; Pan, X.; Liang, J.; Tian, L.; Li, X.; Liu, L.; Xing, Y.; et al. Gut Microbiota-Dependent Marker TMAO in Promoting Cardiovascular Disease: Inflammation Mechanism, Clinical Prognostic, and Potential as a Therapeutic Target. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 1360.

- Hazen, S.L. Gut microbial metabolite TMAO enhances platelet hyperreactivity and thrombosis risk. Cell 2016, 165, 111–124.

- Zhao, J.; Zhang, X.; Liu, H.; Brown, M.A.; Qiao, S. Dietary Protein and Gut Microbiota Composition and Function. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 2019, 20, 145–154.

- Beaumont, M.; Portune, K.J.; Steuer, N.; Lan, A.; Cerrudo, V.; Audebert, M.; Dumont, F.; Mancano, G.; Khodorova, N.; Andriamihaja, M.; et al. Quantity and source of dietary protein influence metabolite production by gut microbiota and rectal mucosa gene expression: A randomized, parallel, double-blind trial in overweight humans. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 106, 1005–1019.

- Karl, J.P.; Berryman, C.E.; Young, A.J.; Radcliffe, P.N.; Branck, T.A.; Pantoja-Feliciano, I.G.; Rood, J.C.; Pasiakos, S.M. Associations between the gut microbiota and host responses to high altitude. Am. J. Physiol Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2018, 315, 1003–1015.

- Barker, H.A. Amino acid degradation by anaerobic bacteria. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1981, 50, 23–40.

- Liu, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, S.; Yang, F.; Thacker, P.A.; Zhang, G.; Qiao, S.; Ma, X.J. Oral administration of Lactobacillus fermentum favors intestinal development and alters the intestinal microbiota in formula-fed piglets. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 860–866.

- Kau, A.L.; Ahern, P.P.; Griffin, N.W.; Goodman, A.L.; Gordon, J.I. Human nutrition, the gut microbiome and the immune system. Nature 2011, 474, 327–336.

- Gensollen, T.; Iyer, S.S.; Kasper, D.L.; Blumberg, R.S. How colonization by microbiota in early life shapes the immune system. Science 2016, 352, 539–544.

- Lang, J.M.; Pan, C.; Cantor, R.M.; Tang, W.H.W.; Garcia-Garcia, J.C.; Kurtz, I.; Hazen, S.L.; Bergeron, N.; Krauss, R.M.; Lusis, A.J. Impact of Individual Traits, Saturated Fat, and Protein Source on the Gut Microbiome. mBio 2018, 9, e01604-18.

- Hayashi, T.; Yamashita, T.; Watanabe, H.; Kami, K.; Yoshida, N.; Tabata, T.; Emoto, T.; Sasaki, N.; Mizoguchi, T.; Irino, Y.; et al. Gut Microbiome and Plasma Microbiome-Related Metabolites in Patients with Decompensated and Compensated Heart Failure. Circ. J. 2018, 83, 182–192.

- Danilo, C.A.; Constantopoulos, E.; McKee, L.A.; Chen, H.; Regan, J.A.; Lipovka, Y.; Lahtinen, S.; Stenman, L.K.; Nguyen, T.-V.V.; Doyle, K.P.; et al. Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis 420 mitigates the pathological impact of myocardial infarction in the mouse. Benef. Microbes 2017, 8, 257–269.

- Farrokhian, A.; Raygan, F.; Soltani, A.; Tajabadi-Ebrahimi, M.; Esfahani, M.S.; Karami, A.A.; Asemi, Z. The Effects of Synbiotic Supplementation on Carotid Intima-Media Thickness, Biomarkers of Inf mation, and Oxidative Stress in People with Overweight, Diabetes, and Coronary Heart Disease: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2019, 11, 133–142.

- Gan, X.T.; Ettinger, G.; Huang, C.X.; Burton, J.P.; Haist, J.V.; Rajapurohitam, V.; Sidaway, J.E.; Martin, G.; Gloor, G.B.; Swann, J.R.; et al. Probiotic administration attenuates myocardial hypertrophy and heart failure following myocardial infarction in the rat. Circ. Heart Fail. 2014, 7, 491.

- Ettinger, G.; Burton, J.P.; Gloor, G.B.; Reidm, G. Lactobacillus rhamnosus GR-1 Attenuates Induction of Hypertrophy in Cardiomyocytes but Not through Secreted Protein MSP-1 (p75). PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0168622.

- Ott, S.J.; El Mokhtari, N.E.; Musfeldt, M.; Hellmig, S.; Freitag, S.; Rehman, A.; Kühbacher, T.; Nikolaus, S.; Namsolleck, P.; Blaut, M.; et al. Detection of diverse bacterial signatures in atherosclerotic lesions of patients with coronary heart disease. Circulation 2006, 113, 929–937.

- McAdow, M.; Kim, H.K.; Dedent, A.C.; Hendrickx, A.P.A.; Schneewind, O.; Missiakas, D.M. Preventing Staphylococcus aureus sepsis through the inhibition of its agglutination in blood. PLoS Pathog. 2011, 7, e1002307.

- Shin, J.H.; Sim, M.; Lee, J.Y.; Shin, D.M. Lifestyle and geographic insights into the distinct gut microbiota in elderly women from two different geographic locations. J. Physiol. Anthropol. 2016, 35, 31.

- Gomez-Arango, L.F.; Barrett, H.; McIntyre, D.; Callaway, L.K.; Morrison, M.; Nitert, M.D. Increased Systolic and Diastolic Blood Pressure Is Associated with Altered Gut Microbiota Composition and Butyrate Production in Early Pregnancy. Hypertension 2016, 68, 974–977.

- Toral, M.; Robles-Vera, I.; de la Visitación, N.; Romero, M.; Yang, T.; Sánchez, M.; Gómez-Guzmán, M.; Jiménez, R.; Raizada, M.K.; Duarte, J. Critical Role of the Interaction Gut Microbiota—Sympathetic Nervous System in the Regulation of Blood Pressure. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 231.

- Xie, J.; Lu, W.; Zhong, L.; Hu, Y.; Li, Q.; Ding, R.; Zhong, Z.; Liu, Z.; Xiao, H.; Xie, D.; et al. Alterations in gut microbiota of abdominal aortic aneurysm mice. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2020, 20, 32.

- Hills, R.D., Jr.; Pontefract, B.A.; Mishcon, H.R.; Black, C.A.; Sutton, S.C.; Theberge, C.R. Gut Microbiome: Profound Implications for Diet and Disease. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1613.

- Boets, E.; Gomand, S.V.; Deroover, L.; Preston, T.; Vermeulen, K.; De Preter, V.; Hamer, H.M.; Van den Mooter, G.; De Vuyst, L.; Courtin, C.M.; et al. Systemic availability and metabolism of colonic-derived short-chain fatty acids in healthy subjects: A stable isotope study. J. Physiol. 2017, 595, 541–555.

- Li, J.; Zhao, F.; Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; Tao, J.; Tian, G.; Wu, S.; Liu, W.; Cui, Q.; Geng, B.; et al. Gut microbiota dysbiosis contributes to the development of hypertension. Microbiome 2017, 5, 14.

- Kelly, T.N.; Bazzano, L.A.; Ajami, N.J.; He, H.; Zhao, J.; Petrosino, J.F.; Correa, A.; He, J. Gut Microbiome Associates with Lifetime Cardiovascular Disease Risk Profile Among Bogalusa Heart Study Participants. Circ. Res. 2016, 119, 956–964.

- Liu, Z.; Li, J.; Liu, H.; Tang, Y.; Zhan, Q.; Lai, W.; Ao, L.; Meng, X.; Ren, H.; Xu, D.; et al. The intestinal microbiota associated with cardiac valve calcification differs from that of coronary artery disease. Atherosclerosis 2019, 284, 121–128.

- Verhaar, B.J.H.; Prodan, A.; Nieuwdorp, M.; Muller, M. Gut Microbiota in Hypertension and Atherosclerosis: A Review. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2982.

- Chen, X.F.; Ren, S.C.; Tang, G.; Wu, C.; Chen, X.; Tang, X.Q. Short-chain fatty acids in blood pressure, friend or foe. Chin. Med. J. 2021, 134, 2393–2394.

- Verhaar, B.J.H.; Collard, D.; Prodan, A.; Levels, J.H.M.; Zwinderman, A.H.; Bäckhed, F.; Vogt, L.; Peters, M.J.L.; Muller, M.; Nieuwdorp, M.; et al. Associations between gut microbiota, faecal short-chain fatty acids, and blood pressure across ethnic groups: The HELIUS study. Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, 4259–4267.

- Huart, J.; Leenders, J.; Taminiau, B.; Descy, J.; Saint-Remy, A.; Daube, G.; Krzesinski, J.M.; Melin, P.; De Tullio, P.; Jouret, F. Gut Microbiota and Fecal Levels of Short-Chain Fatty Acids Differ Upon 24-Hour Blood Pressure Levels in Men. Hypertension 2019, 74, 1005–1013.

- De La Cuesta-Zuluaga, J.; Mueller, N.T.; Alvarez, R.Q.; Velásquez-Mejía, E.P.; Sierra, J.A.; Corrales-Agudelo, V.; Carmona, J.A.; Abad, J.M.; Escobar, J.S. Higher Fecal Short-Chain Fatty Acid Levels Are Associated with Gut Microbiome Dysbiosis, Obesity, Hypertension and Cardiometabolic Disease Risk Factors. Nutrients 2018, 11, 51.

- Le Poul, E.; Loison, C.; Struyf, S.; Springael, J.Y.; Lannoy, V.; Decobecq, M.E.; Brezillon, S.; Dupriez, V.; Vassart, G.; Van Damme, J.; et al. Functional characterization of human receptors for short chain fatty acids and their role in polymorphonuclear cell activation. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 25481–25489.

- Pluznicki, J.L. Microbial Short-Chain Fatty Acids and Blood Pressure Regulation. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2017, 19, 25.

- Ohira, H.; Tsutsui, W.; Fujioka, Y. Are Short Chain Fatty Acids in Gut Microbiota Defensive Players for Inflammation and Atherosclerosis? J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2017, 24, 660–672.

- Miyamoto, J.; Kasubuchi, M.; Nakajima, A.; Irie, J.; Itoh, H.; Kimura, I. The role of short-chain fatty acid on blood pressure regulation. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 2016, 25, 379–383.

- Pluznick, J. A novel SCFA receptor, the microbiota, and blood pressure regulation. Gut Microbes 2014, 5, 202–207.

- Yang, T.; Magee, K.L.; Colon-Perez, L.M.; Larkin, R.; Liao, Y.S.; Balazic, E.; Cowart, J.R.; Arocha, R.; Redler, T.; Febo, M.; et al. Impaired butyrate absorption in the proximal colon, low serum butyrate and diminished central effects of butyrate on blood pressure in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Acta Physiol. 2019, 226, e13256.

- Lal, S.; Kirkup, A.J.; Brunsden, A.M.; Thompson, D.G.; Grundy, D. Vagal afferent responses to fatty acids of different chain length in the rat. Am. J. Physiol. Liver Physiol. 2001, 281, G907–G915.

- Marques, F.Z.; Nelson, E.; Chu, P.Y.; Horlock, D.; Fiedler, A.; Ziemann, M.; Tan, J.K.; Kuruppu, S.; Rajapakse, N.W.; El-Osta, A.; et al. High-fiber diet and acetate supplementation change the gut microbiota and prevent the development of hypertension and heart failure in hypertensive mice. Circulation 2017, 135, 964–977.

- Poll, B.G.; Xu, J.; Jun, S.; Sanchez, J.; Zaidman, N.A.; He, X.; Lester, L.; Berkowitz, D.E.; Paolocci, N.; Gao, W.D.; et al. Acetate, a Short-Chain Fatty Acid, Acutely Lowers Heart Rate and Cardiac Contractility Along with Blood Pressure. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2021, 377, 39–50.

- Bartolomaeus, H.; Balogh, A.; Yakoub, M.; Homann, S.; Markó, L.; Höges, S.; Tsvetkov, D.; Krannich, A.; Wundersitz, S.; Avery, E.G.; et al. Short-Chain Fatty Acid Propionate Protects from Hypertensive Cardiovascular Damage. Circulation 2019, 139, 1407–1421.

- Wang, L.; Zhu, Q.; Lu, A.; Liu, X.; Zhang, L.; Xu, C.; Liu, X.; Li, H.; Yang, T. Sodium butyrate suppresses angiotensin II-induced hypertension by inhibition of renal (pro)renin receptor and intrarenal renin-angiotensin system. J. Hypertens. 2017, 35, 1899–1908.

- Trehan, N.; Afonso, L.; Levine, D.L.; Levy, P.D. Vitamin D Deficiency, Supplementation, and Cardiovascular Health. Crit. Pathw. Cardiol. 2017, 16, 109–118.

- Zuo, K.; Li, J.; Xu, Q.; Hu, C.; Gao, Y.; Chen, M.; Hu, R.; Liu, Y.; Chi, H.; Yin, Q.; et al. Dysbiotic gut microbes may contribute to hypertension by limiting vitamin D production. Clin. Cardiol. 2019, 42, 710–719.

- Charoenngam, N.; Shirvani, A.; Kalajian, T.A.; Song, A.; Holick, M.F. The Effect of Various Doses of Oral Vitamin D3 Supplementation on Gut Microbiota in Healthy Adults: A Randomized, Double-blinded, Dose-response Study. Anticancer Res. 2020, 40, 551–556.

- Tian, Y.; Nichols, R.G.; Cai, J.; Patterson, A.D.; Cantorna, M.T. Vitamin A deficiency in mice alters host and gut microbial metabolism leading to altered energy homeostasis. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2018, 54, 28–34.

- Tilg, H.; Moschen, A.R. Microbiota and diabetes: An evolving relationship. Gut 2014, 63, 1513–1521.

- Everard, A.; Belzer, C.; Geurts, L.; Ouwerkerk, J.P.; Druart, C.; Bindels, L.B.; Guiot, Y.; Derrien, M.; Muccioli, G.G.; Delzenne, N.M.; et al. Cross-talk between Akkermansia muciniphila and intestinal epithelium controls diet-induced obesity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 9066–9071.

- Tsai, H.J.; Tsai, W.C.; Hung, W.C.; Hung, W.W.; Chang, C.C.; Dai, C.Y.; Tsai, Y.C. Gut Microbiota and Subclinical Cardiovascular Disease in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2679.

- Mushtaq, N.; Hussain, S.; Zhang, S.; Yuan, L.; Li, H.; Ullah, S.; Wang, Y.; Xu, J. Molecular characterization of alterations in the intestinal microbiota of patients with grade 3 hypertension. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2019, 44, 513–522.

- Crovesy, L.; Masterson, D.; Rosado, E.L. Profile of the gut microbiota of adults with obesity: A systematic review. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 74, 1251–1262.

- Marzullo, P.; Di Renzo, L.; Pugliese, G.; De Siena, M.; Barrea, L.; Muscogiuri, G.; Colao, A.; Savastano, S. From obesity through gut microbiota to cardiovascular diseases: A dangerous journey. Int. J. Obes. Suppl. 2020, 10, 35–49.

- Sawicka-Smiarowska, E.; Bondarczuk, K.; Bauer, W.; Niemira, M.; Szalkowska, A.; Raczkowska, J.; Kwasniewski, M.; Tarasiuk, E.; Dubatowka, M.; Lapinska, M.; et al. Gut Microbiome in Chronic Coronary Syndrome Patients. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 5074.

- Turnbaugh, P.J.; Hamady, M.; Yatsunenko, T.; Cantarel, B.L.; Duncan, A.; Ley, R.E.; Sogin, M.L.; Jones, W.J.; Roe, B.A.; Affourtit, J.P.; et al. A core gut microbiome in obese and lean twins. Nature 2009, 457, 480–484.

- Ley, R.E.; Backhed, F.; Turnbaugh, P.; Lozupone, C.A.; Knight, R.D.; Gordon, J.I. Obesity alters gut microbial ecology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 11070–11075.

- Sze, M.A.; Schloss, P.D. Looking for a signal in the noise: Revisiting obesity and the microbiome. mBio 2016, 7, e01018-16.

More