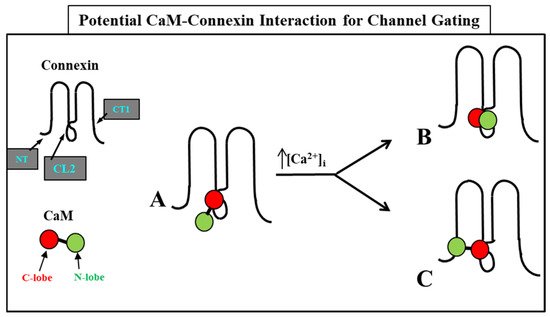

In the past four decades numerous findings have indicated that gap junction channel gating is mediated by intracellular calcium concentrations ([Ca2+i]) in the high nanomolar range via calmodulin (CaM). We believe that CaM directly closes the channel by a cork-like gating mechanism.

- connexins

- innexins

- channel gating

- calcium

- calmodulin

- cell communication

- cell-to-cell channels

- cell coupling

- cell uncoupling

1. Introduction

2. Cytosolic Calcium and Gap Junction Channel Gating

3. Evidence for Calmodulin Role in Gap Junction Channel Gating

4. Calmodulin-Connexinrk Interaction—Are There CalmoduGating Modelin Binding Sites in Connexins?

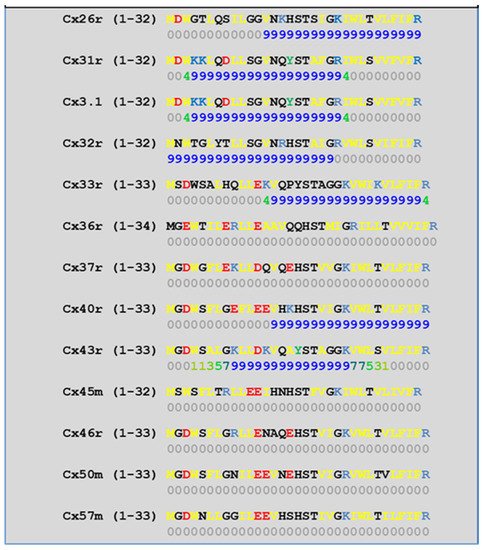

4.1. NH2-Terminus (NT) and Initial COOH-Terminus (CT1) CaM-Binding Sites

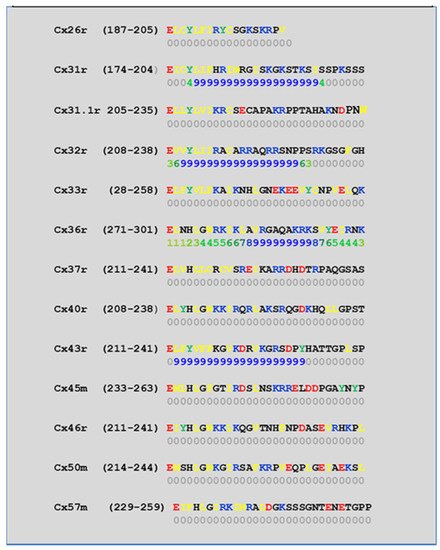

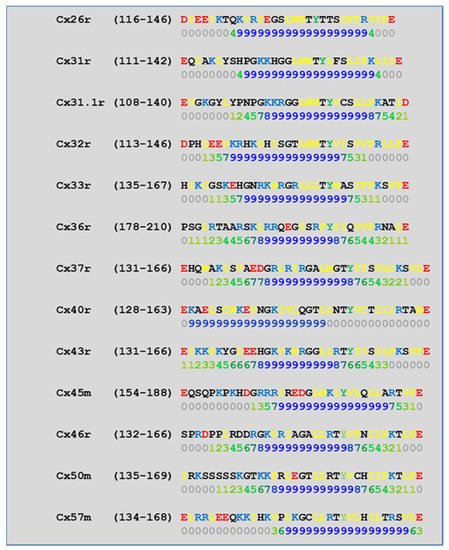

4.2. Cytoplasmic Loop (CL) CaM-Binding Sites

| Connexin | NT Site | CL2 Site | CT1 Site |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cx26r | Yes | Yes | |

| Cx31r | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Cx31.1r | Yes | Yes | |

4.3. CaM Is Anchored to Connexins at Resting [Ca2+]i

| KD (with Ca2+) | KD (Ca2+-Free) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cx32 | 40 ± 4 nM | 280 ± 10 nM | ||||

| Cx35 | 31 ± 2 nM | 2.67 ± 0.09 µM | ||||

| Cx45 | 75 ± 4 nM | 78 ± 1 nM | Cx32r | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Cx57 | 60 ± 6 nM | 52 ± 14 nM | Cx33r | Yes | Yes | |

| Cx36r | Yes | Yes | ||||

| Cx37r | Yes | |||||

| Cx40r | Yes | Yes | ||||

| Cx43r | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| Cx45m | Yes | |||||

| Cx46r | Yes | |||||

| Cx50m | Yes | |||||

| Cx57m | Yes |

5. Calmodulin-Cork Gating Model

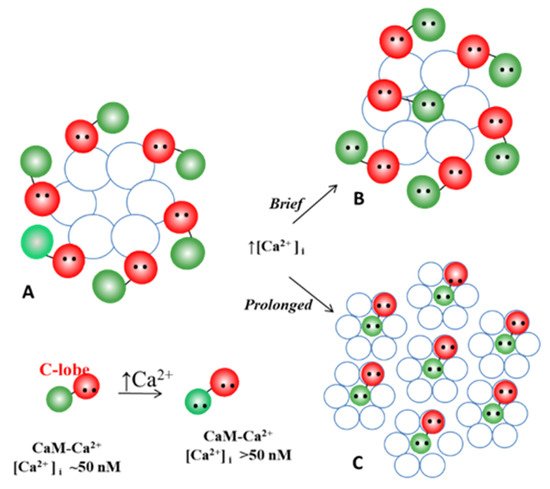

54.1. Ca-CaM-Cork Gating Mechanism

54.2. CaM-Cork Gating Mechanism

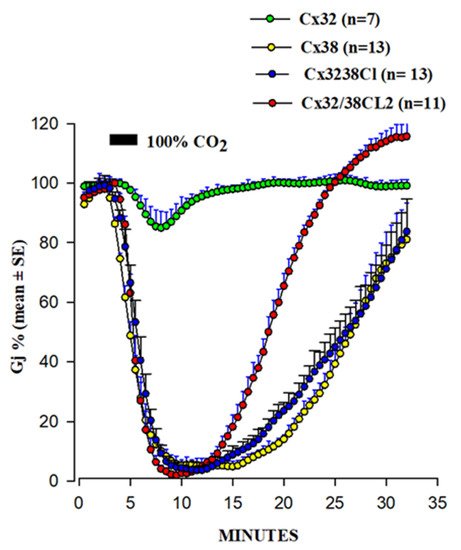

54.2.1. CaM-Cork Gating in Mutant-Cx32 Channels

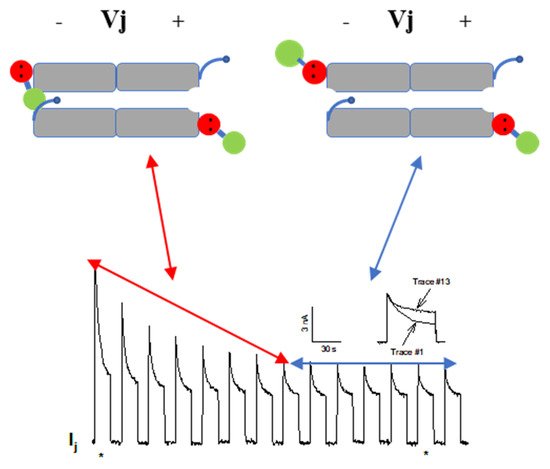

54.2.2. CaM-Cork Gating of Homotypic Cx32 Channels Can Be Activated by Large Vj Pulses

54.2.3. CaM-Cork Gating in Homotypic Cx45 Channels

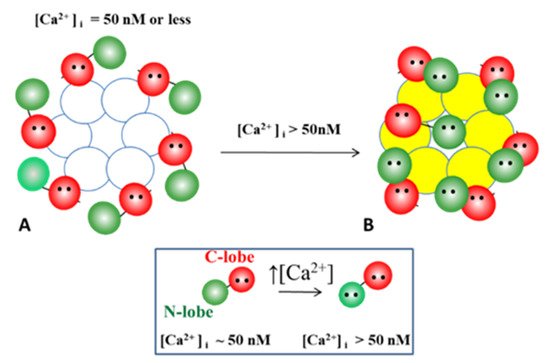

54.2.4. How Many CaM’s Lobes Are Needed to Close a Channel?

54.3. Ca-CaM-Locked-Gate—Irreversible Channel Gating

54.3.1. Gap Junction Crystallization and the Locked-Gate Model

54.3.2. What Causes Gap Junction Crystallization?

6. The Calmodulin-Cork Model Is Supported by X-ray Diffraction Images of Isolated Gap Junction Channels in Closed State

We are aware that the mechanism for gap junction crystallization we are proposing is highly speculative and needs to be experimentally tested. Perhaps, future work could test this idea by attempting to detect biochemically the presence of CaM molecule in isolated gap junctions. However, one should realize that if only two CaM molecules are bound to each channel of crystalline gap junction fragments, the CaM will only represent 14.3% of the proteins, as each channel is made of twelve connexin monomers.

- The Calmodulin-Cork Model Is Supported by X-ray Diffraction Images of Isolated Gap Junction Channels in Closed State

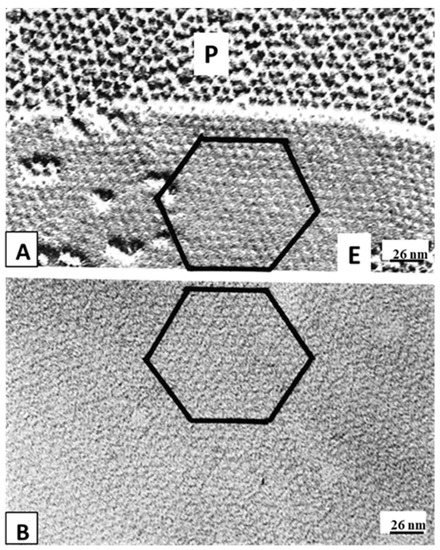

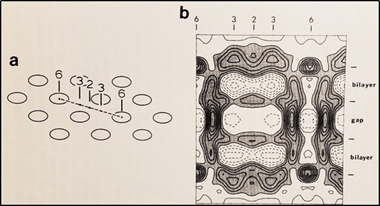

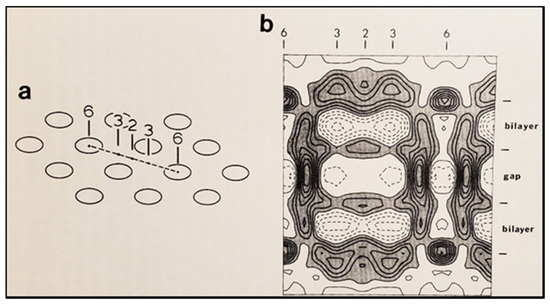

In the early 1980s, Makowski and coworkers described the structure of crystalline (hexagonal) gap junctions isolated from mouse liver in a high-resistance configuration (closed channels) by analyzing X-ray diffraction data at 18 Å resolution (Figures 18 and 19B) [120,121]. The channels’ gated condition of these isolated gap junctions was proven by the evidence that the channels were impermeable to sucrose [120]; in their words: “Analysis of diffraction patterns from isolated gap junctions in 50% sucrose shows that the sucrose fills the extracellular gap but fails to enter the channel. It is possible that the channel is closed at both cytoplasmic surfaces, excluding sucrose. This suggests that the isolated junctions are in a high resistance state” [120]. Indeed, the three-dimensional map of the electron density demonstrated that the channels were blocked at both cytoplasmic ends by a small particle; in their words: “Its position blocking the channel suggests that it may comprise a gating structure responsible for the control of channel permeability, X-ray diffraction studies of junctions in varying concentrations of sucrose (Makowski et al. 1984a) [122] indicated that in these preparations the channel was closed to the penetration of sucrose and that a solvent region approximately 100 Å long and centered on the six fold axis remained free of sucrose” [121].

. Diagram of the three-dimensional structure of a frozen-hydrated gap junction isolated from mouse liver and solved to 18 Å resolution by X-ray diffraction. The channel “6” in (a,b) is impermeable to 50% sucrose, proving that it is closed at each cytoplasmic end by a particle that prevents sucrose entry. This proves that the channels of isolated (crystalline) junctions are in closed state (Ca-CaM locked state). Reproduced from Ref. [121] with permission from the Journal of Molecular Biology and the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratories.

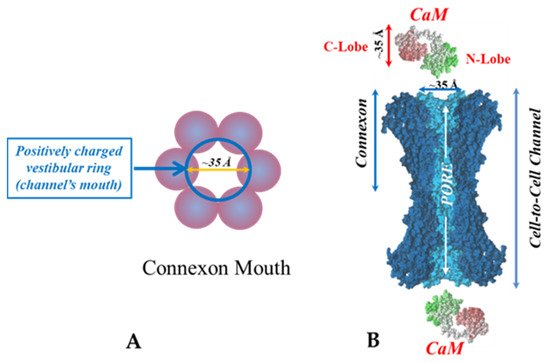

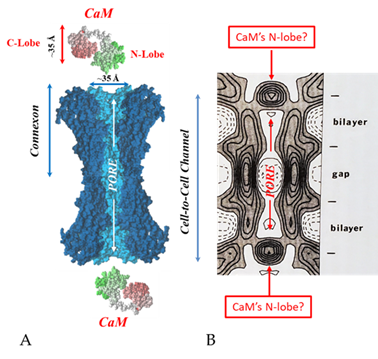

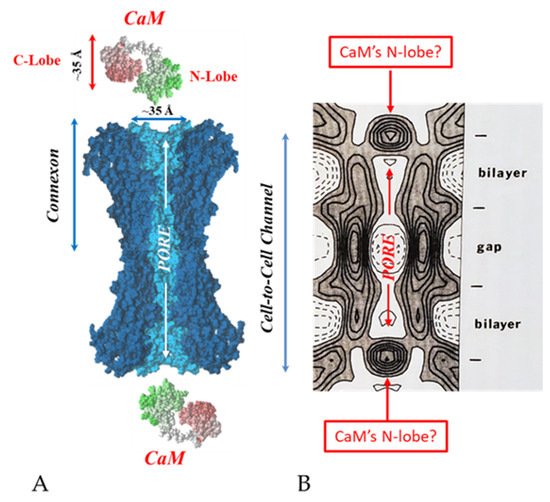

. Both the positively charged channel’s mouth and the negatively charged CaM lobes are ~35 Å in size (A). Thus, a CaM lobe could fit well within the positively charged connexon’s mouth (A). Significantly, the three-dimensional structure of gap junctions isolated from mouse liver (B) demonstrates that the channel of isolated (crystalline) junctions is impermeable to 50% sucrose, proving that it is closed at each cytoplasmic end by a particle that prevents sucrose entry (B). Our hypothesis is that the blocking particle is the CaM’s N-lobe (B). Both the CaM and connexon images (A) were provided by Dr. Francesco Zonta (VIMM, University of Padua, Italy. (B) was reproduced from Ref. [121] with permission from the Journal of Molecular Biology and the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratories.

Diagram of the three-dimensional structure of a frozen-hydrated gap junction isolated from mouse liver and solved to 18 Å resolution by X-ray diffraction. The channel “6” in (

,

) is impermeable to 50% sucrose, proving that it is closed at each cytoplasmic end by a particle that prevents sucrose entry. This proves that the channels of isolated (crystalline) junctions are in closed state (Ca-CaM locked state). Reproduced from Ref. [121] with permission from the Journal of Molecular Biology and the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratories.

Both the positively charged channel’s mouth and the negatively charged CaM lobes are ~35 Å in size (

). Thus, a CaM lobe could fit well within the positively charged connexon’s mouth (

). Significantly, the three-dimensional structure of gap junctions isolated from mouse liver (

) demonstrates that the channel of isolated (crystalline) junctions is impermeable to 50% sucrose, proving that it is closed at each cytoplasmic end by a particle that prevents sucrose entry (

). Our hypothesis is that the blocking particle is the CaM’s N-lobe (

). Both the CaM and connexon images (

) were provided by Dr. Francesco Zonta (VIMM, University of Padua, Italy. (

) was reproduced from Ref. [121] with permission from the Journal of Molecular Biology and the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratories.

Significantly, the blocking particle, spherical in shape, is approximately 30–35 Ǻ in diameter [121] (Figures 18 and 19B), which is remarkably similar in size to a CaM lobe (Figure 19A). Indeed, in their words: “The channel has a diameter of 20–30 Ǻ along most of its length but appears to narrow to a minimum diameter of about 15 Ǻ in the extracellular half of the bilayer … Both the sucrose results and the three-dimensional map are consistent with the idea that a structure located near the cytoplasmic surface of the membraned is blocking the channel in these preparations” [121]. These studies support our evidence that gap junctions with crystalline (hexagonal) channel arrays are in an uncoupled (gated) state (Ca-CaM locked gate, Figures 13-16) [11,17,18,127–130] and suggest that a CaM lobe is gating the channel.

- Conclusions and Future Perspectives

This article has reviewed four decades of data supporting the direct role of CaM in gap junction channel gating. The Ca-CaM-cork gating mechanism [113], proposed over two decades ago [112], is based on evidence from the effect of CaM inhibitors, the inhibition of CaM expression, the expression of a CaM mutant (CaMCC) with higher Ca2+-sensitivity, CaM-connexin co-localization at gap junctions, the presence of high-affinity CaM-binding sites in connexins, the expression of connexin mutants, the gating effect of repeated large Vj pulses, data at the single channel level, the recovery of lost gating competency by addition of Ca-CaM to internally perfused crayfish axons and, finally, X-ray diffraction data on isolated gap junction fragments.

One may ask: why is it important to understand in detail the gating mechanism of gap junction channels? It is important not only because cell–cell uncoupling is more than just a safety mechanism for protecting healthy cells from damaged neighbors (healing over), but because the gating sensitivity to [Ca2+]i in the high nanomolar range indicates that the fine modulation of direct cell–cell communication provides cells with the means for regulating tissue homeostasis. In addition, and more importantly, the field should be encouraged to test the effect of recently discovered disease-causing CaM mutants on gap junction function [135].

Indeed, recent evidence of diseases caused by CaM mutations [136–141] suggests the potential role of CaM mutants in diseases affecting gap junction function. Almost two dozen CaM mutations have been found to cause cardiac malfunctions, most of which occur in the CaM’s C-lobe, one in the N-lobe, and one in the linker between the C- and N-lobes. In most cases the electrocardiogram (ECG) demonstrates the presence of Long QT Syndrome (LQTS), a change that affects the electrical activity of the heart, which is often associated with Catecholaminergic Polymorphic Ventricular Tachycardia (CPVT) phenotype and Idiopathic Ventricular Fibrillation (IVF). CPVT patients manifest ventricular tachycardia that can lead to death by ventricular fibrillation. In most cases, cardiac malfunctions have been attributed to the effect of CaM mutations on the ryanodine receptor (RyR2) and the cardiac L-type voltage-gated Ca2+ channel. However, other membrane channels, potential targets of CaM mutants, have also been suggested. Curiously, however, in spite of strong evidence for the direct CaM role in gap junction channel regulation, the potential consequences of these CaM mutants on direct cell–cell communication—a mechanism fundamental for the function of virtually all vertebrate and invertebrate organs—have not yet been addressed. Therefore, it is clear that future efforts should be aimed at testing the effect of these CaM mutants, and the future discovered CaM mutants, on gap junction mediated communication [135].

Authore 18

and F Contrigbure 19B), which is remarkably similar in size to a CaM lobe (tions: C.P. is the principal investigator. L.M.L.P., Research Assistant, has performed the general lab work and the technical work for preparation and injection of oocytes

Fundigung:This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Intere 19

A). Indeed, in their words: “The channel has a diameter of 20–30 Ǻ along most of its length but appears to narrow to a minimum diameter of about 15 Ǻ in the extracellular half of the bilayer. Both the sucrose results and the three-dimensional map are consistent with the idea that a structure located near the cytoplasmic surface of the membraned is blocking the channel in these preparations” [121]. These studies support our evidence that gap junctions with crystalline (hexagonal) channel arrays are in an uncoupled (gated) state (Ca-CaM locked gate, Figst:The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

We are aware that the mechanism for gap junction crystallization we are proposing is highly speculative and needs to be experimentally tested. Perhaps, future work could test this idea by attempting to detect biochemically the presence of CaM molecule in isolated gap junctions. However, one should realize that if only two CaM molecules are bound to each channel of crystalline gap junction fragments, the CaM will only represent 14.3% of the proteins, as each channel is made of twelve connexin monomers.

- The Calmodulin-Cork Model Is Supported by X-ray Diffraction Images of Isolated Gap Junction Channels in Closed State

In the early 1980s, Makowski and coworkers described the structure of crystalline (hexagonal) gap junctions isolated from mouse liver in a high-resistance configuration (closed channels) by analyzing X-ray diffraction data at 18 Å resolution (Figures 18 and 19B) [120,121]. The channels’ gated condition of these isolated gap junctions was proven by the evidence that the channels were impermeable to sucrose [120]; in their words: “Analysis of diffraction patterns from isolated gap junctions in 50% sucrose shows that the sucrose fills the extracellular gap but fails to enter the channel. It is possible that the channel is closed at both cytoplasmic surfaces, excluding sucrose. This suggests that the isolated junctions are in a high resistance state” [120]. Indeed, the three-dimensional map of the electron density demonstrated that the channels were blocked at both cytoplasmic ends by a small particle; in their words: “Its position blocking the channel suggests that it may comprise a gating structure responsible for the control of channel permeability, X-ray diffraction studies of junctions in varying concentrations of sucrose (Makowski et al. 1984a) [122] indicated that in these preparations the channel was closed to the penetration of sucrose and that a solvent region approximately 100 Å long and centered on the six fold axis remained free of sucrose” [121].

Significantly, the blocking particle, spherical in shape, is approximately 30–35 Ǻ in diameter [121] (Figures 18 and 19B), which is remarkably similar in size to a CaM lobe (Figure 19A). Indeed, in their words: “The channel has a diameter of 20–30 Ǻ along most of its length but appears to narrow to a minimum diameter of about 15 Ǻ in the extracellular half of the bilayer … Both the sucrose results and the three-dimensional map are consistent with the idea that a structure located near the cytoplasmic surface of the membraned is blocking the channel in these preparations” [121]. These studies support our evidence that gap junctions with crystalline (hexagonal) channel arrays are in an uncoupled (gated) state (Ca-CaM locked gate, Figures 13-16) [11,17,18,127–130] and suggest that a CaM lobe is gating the channel.

- Conclusions and Future Perspectives

This article has reviewed four decades of data supporting the direct role of CaM in gap junction channel gating. The Ca-CaM-cork gating mechanism [113], proposed over two decades ago [112], is based on evidence from the effect of CaM inhibitors, the inhibition of CaM expression, the expression of a CaM mutant (CaMCC) with higher Ca2+-sensitivity, CaM-connexin co-localization at gap junctions, the presence of high-affinity CaM-binding sites in connexins, the expression of connexin mutants, the gating effect of repeated large Vj pulses, data at the single channel level, the recovery of lost gating competency by addition of Ca-CaM to internally perfused crayfish axons and, finally, X-ray diffraction data on isolated gap junction fragments.

One may ask: why is it important to understand in detail the gating mechanism of gap junction channels? It is important not only because cell–cell uncoupling is more than just a safety mechanism for protecting healthy cells from damaged neighbors (healing over), but because the gating sensitivity to [Ca2+]i in the high nanomolar range indicates that the fine modulation of direct cell–cell communication provides cells with the means for regulating tissue homeostasis. In addition, and more importantly, the field should be encouraged to test the effect of recently discovered disease-causing CaM mutants on gap junction function [135].

Indeed, recent evidence of diseases caused by CaM mutations [136–141] suggests the potential role of CaM mutants in diseases affecting gap junction function. Almost two dozen CaM mutations have been found to cause cardiac malfunctions, most of which occur in the CaM’s C-lobe, one in the N-lobe, and one in the linker between the C- and N-lobes. In most cases the electrocardiogram (ECG) demonstrates the presence of Long QT Syndrome (LQTS), a change that affects the electrical activity of the heart, which is often associated with Catecholaminergic Polymorphic Ventricular Tachycardia (CPVT) phenotype and Idiopathic Ventricular Fibrillation (IVF). CPVT patients manifest ventricular tachycardia that can lead to death by ventricular fibrillation. In most cases, cardiac malfunctions have been attributed to the effect of CaM mutations on the ryanodine receptor (RyR2) and the cardiac L-type voltage-gated Ca2+ channel. However, other membrane channels, potential targets of CaM mutants, have also been suggested. Curiously, however, in spite of strong evidence for the direct CaM role in gap junction channel regulation, the potential consequences of these CaM mutants on direct cell–cell communication—a mechanism fundamental for the function of virtually all vertebrate and invertebrate organs—have not yet been addressed. Therefore, it is clear that future efforts should be aimed at testing the effect of these CaM mutants, and the future discovered CaM mutants, on gap junction mediated communication [135].

Authore 13

, F Contrigbure 14,tions: C.P. is the principal investigator. L.M.L.P., Research Assistant, has performed the general lab work and the technical work for preparation and injection of oocytes

Fundigurng:This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Inte 15

and Figure 16) [11][17][18][127][128][129][130] and suggest that a CaM lobe is gating the channel.7. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

st: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Stough, H.B. Giant nerve fibers of the earthworn.

- Comp. Neurol.

- 1926

- ,

- 40

- , 409–463.

- Stough, H.B. Polarization of the giant nerve fibers of the earthworm.

- Comp. Neurol.

- 1930

- ,

- 50

- , 217–229.

- Weidmann, S. The electrical constants of Purkinje fibres.

- Physiol.

- 1952

- ,

- 118

- , 348–360.

- Kanno, Y.; Loewenstein, W.R. Low-resistance coupling between gland cells. Some observations on intercellular contact membranes and intercellular space.

- Nature

- 1964

- ,

- 201

- , 194–195.

- Loewenstein, W.R.; Kanno, Y. Studies on an epithelial (gland) cell junction. i. modifications of surface membrane permeability.

- Cell Biol. 1964, 22, 565–586.

- Kuffler, S.W.; Potter, D.D. Glia in the leech central nervous system: Physiological properties and neuron-glia relationship. Neurophysiol. 1964, 27, 290–320.

- Rothschuh, K.E. Über den aufbau des herzmuskels aus "elektrophysiologischen elementen". Der Dtsch. Ges. Fur Kreislaufforsch. 1950, 16, 226–232.

- Rothschuh, K.E. Über den funktionellen aufbaudes herzens aus elektrophysiologischen Elementen und üiber den mechanismus der erregungsleitung im herzen. Pflüg. Arch. 1951, 253, 238–251.

- De Mello, W.C.; Motta, G.E.; Chapeau, M. A study on the healing-over of myocardial cells of toads. Res. 1969, 24, 475–487.

- Engelmann, T.W. Vergleichende Untersuchungen zur Lehre von der Muskel und Nervenelektricität. Pflügers Arch. 1877, 15, 116–148.

- Peracchia, C. Structural correlates of gap junction permeation. Rev. Cytol. 1980, 66, 81–146.

- Peracchia, C. Cell coupling. In Membrane Structure and Dynamics; Martonosi, A.N., Ed. Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985; pp. 81–130.

- Rose, B.; Loewenstein, W.R. Permeability of cell junction depends on local cytoplasmic calcium activity. Nature 1975, 254, 250–252.

- Loewenstein, W.R. Junctional intercellular communication: The cell-to-cell membrane channel. Rev. 1981, 61, 829–913.

- Bennett, M.V.L. Junctional permeability. In Intercellular Junctions and Synapses; Feldman, J., Gilula, N.B., Pitts, J.D., Eds.; John Wiley and Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1978; pp. 25–36.

- Délèze, J. Calcium ions and the healing over of heart fibers. In Electrophysiology of the Heart; Taccardi, B., Marchetti, C., Eds.; Pergamon Press: Oxford, UK, 1965; pp. 147–148.

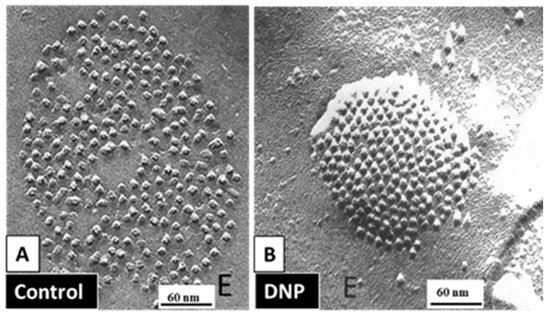

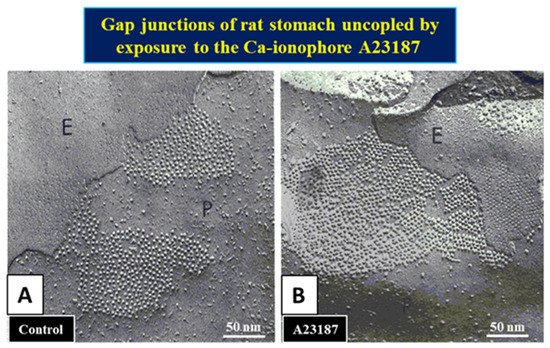

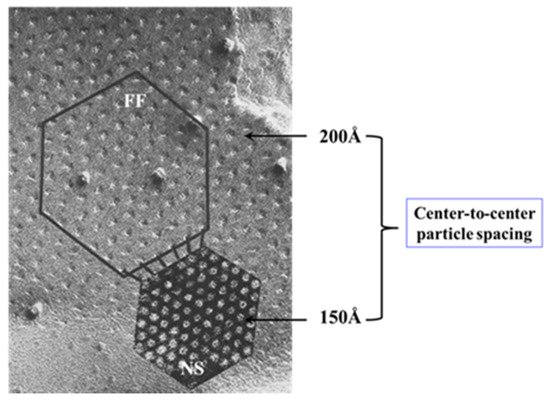

- Peracchia, C. Calcium effects on gap junction structure and cell coupling. Nature 1978, 271, 669–671.

- Peracchia, C.; Peracchia, L.L. Gap junction dynamics: Reversible effects of divalent cations. Cell Biol. 1980, 87, 708–718.

- Peracchia, C. Chemical gating of gap junction channels; roles of calcium, pH and calmodulin. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Biomembr. 2004, 1662, 61–80.

- De Mello, W.C. Influence of the sodium pump on intercellular communication in heart fibres: Effect of intracellular injection of sodium ion on electrical coupling. Physiol. 1976, 263, 171–197.

- Loewenstein, W.R. Permeable junctions. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 1975, 40, 49–63.

- Rose, B.; Loewenstein, W.R. Permeability of a cell junction and the local cytoplasmic free ionized calcium concentration: A study with aequorin. Membr. Biol. 1976, 28, 87–119.

- Délèze, J.; Loewenstein, W.R. Permeability of a cell junction during intracellular injection of divalent cations. Membr. Biol. 1976, 28, 71–86.

- De Mello, W.C. Effect of intracellular injection of calcium and strontium on cell communication in heart. Physiol. 1975, 250, 231–245.

- Bernardini, G.; Peracchia, C.; Venosa, R.A. Healing-over in rat crystalline lens. Physiol. 1981, 320, 187–192.

- Oliveira-Castro, G.M.; Loewenstein, W.R. Junctional membrane permeability: Effects of divalent cations. Membr. Biol. 1971, 5, 51–77.

- Spray, D.C.; Stern, J.H.; Harris, A.L.; Bennett, M.V. Gap junctional conductance: Comparison of sensitivities to H and Ca ions. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1982, 79, 441–445.

- Noma, A.; Tsuboi, N. Dependence of junctional conductance on proton, calcium and magnesium ions in cardiac paired cells of guinea-pig. Physiol. 1987, 382, 193–211.

- Noma, A.; Tsuboi, N. Direct measurement of the gap junctional conductance under the influence of Ca2+ in dissociated paired myocytes of guinea-pig. Heart J. 1986, 27 (Suppl. 1), 161–166.

- Dekker, L.R.; Fiolet, J.W.; VanBavel, E.; Coronel, R.; Opthof, T.; Spaan, J.A.; Janse, M.J. Intracellular Ca2+, intercellular electrical coupling, and mechanical activity in ischemic rabbit papillary muscle. Effects of preconditioning and metabolic blockade. Res. 1996, 79, 237–246.

- Peracchia, C. Effects of caffeine and ryanodine on low pHi-induced changes in gap junction conductance and calcium concentration in crayfish septate axons. Membr. Biol. 1990, 117, 79–89.

- Peracchia, C. Increase in gap junction resistance with acidification in crayfish septate axons is closely related to changes in intracellular calcium but not hydrogen ion concentration. Membr. Biol. 1990, 113, 75–92.

- Neyton, J.; Trautmann, A. Single-channel currents of an intercellular junction. Nature 1985, 317, 331–335.

- Lazrak, A.; Peracchia, C. Gap junction gating sensitivity to physiological internal calcium regardless of pH in Novikoff hepatoma cells. J. 1993, 65, 2002–2012.

- Lazrak, A.; Peres, A.; Giovannardi, S.; Peracchia, C. Ca-mediated and independent effects of arachidonic acid on gap junctions and Ca-independent effects of oleic acid and halothane. J. 1994, 67, 1052–1059.

- Enkvist, M.O.; McCarthy, K.D. Astroglial gap junction communication is increased by treatment with either glutamate or high K+ concentration. Neurochem. 1994, 62, 489–495.

- Cotrina, M.L.; Kang, J.; Lin, J.H.; Bueno, E.; Hansen, T.W.; He, L.; Liu, Y.; Nedergaard, M. Astrocytic gap junctions remain open during ischemic conditions. Neurosci. 1998, 18, 2520–2537.

- Giaume, C.; Venance, L. Characterization and regulation of gap junction channels in cultured astrocytes. In Gap Junctions in the Nervous System; Spray, D.C., Dermietzel, R., Eds.; R.G Landes Medical Pub.: Austin, TX, USA, 1996; pp. 135–157.

- Crow, J.M.; Atkinson, M.M.; Johnson, R.G. Micromolar levels of intracellular calcium reduce gap junctional permeability in lens cultures. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1994, 35, 3332–3341.

- Mears, D.; Sheppard, N.F., Jr.; Atwater, I.; Rojas, E. Magnitude and modulation of pancreatic beta-cell gap junction electrical conductance in situ. Membr. Biol. 1995, 146, 163–176.

- Dakin, K.; Zhao, Y.; Li, W.H. LAMP, a new imaging assay of gap junctional communication unveils that Ca2+ influx inhibits cell coupling. Methods 2005, 2, 55–62.

- Xu, Q.; Kopp, R.F.; Chen, Y.; Yang, J.J.; Roe, M.W.; Veenstra, R.D. Gating of connexin 43 gap junctions by a cytoplasmic loop calmodulin binding domain. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2012, 302, C1548–C1556.

- Iwatsuki, N.; Petersen, O.H. Membrane potential, resistance, and intercellular communication in the lacrimal gland: Effects of acetylcholine and adrenaline. Physiol. 1978, 275, 507–520.

- Iwatsuki, N.; Petersen, O.H. Pancreatic acinar cells: Acetylcholine-evoked electrical uncoupling and its ionic dependency. Physiol. 1978, 274, 81–06.

- Iwatsuki, N.; Petersen, O.H. Electrical coupling and uncoupling of exocrine acinar cells. Cell Biol. 1978, 79 Pt 1, 533–545.

- Matthews, E.K.; Petersen, O.H. Pancreatic acinar cells: Ionic dependence of the membrane potential and acetycholine-induced depolarization. Physiol. 1973, 231, 283–295.

- Scheele, G.A.; Palade, G.E. Studies on the guinea pig pancreas. Parallel discharge of exocrine enzyme activities. Biol. Chem. 1975, 250, 2660–2670.

- Ochs, D.L.; Korenbrot, J.I.; Williams, J.A. Intracellular free calcium concentrations in isolated pancreatic acini; effects of secretagogues. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1983, 117, 122–128.

- Lurtz, M.M.; Louis, C.F. Calmodulin and protein kinase C regulate gap junctional coupling in lens epithelial cells. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2003, 285, C1475–C1482.

- Peracchia, C. Gap Junction Stucture and Chemical Regulation. Direct Calmodulin Role in Cell-to-Cell Channel Gating; Academic Press. An Imprint of Elsevier: London, UK, 2019.

- Peracchia, C. Calmodulin-mediated regulation of gap junction channels. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 485.

- Zou, J.; Salarian, M.; Chen, Y.; Veenstra, R.; Louis, C.F.; Yang, J.J. Gap junction regulation by calmodulin. FEBS Lett. 2014, 588,1430–1438.

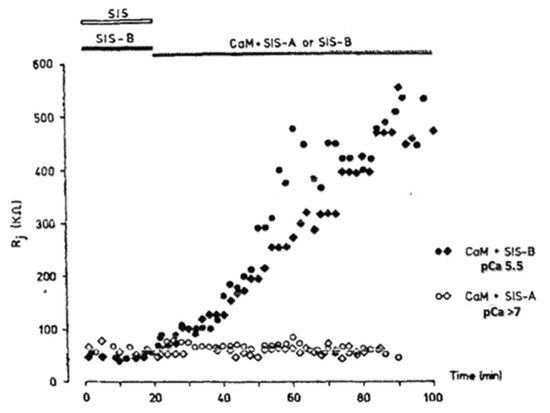

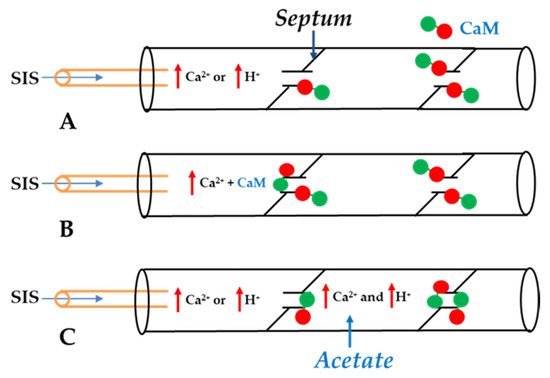

- Johnston, M.F.; Ramon, F. Electrotonic coupling in internally perfused crayfish segmented axons. Physiol. 1981, 317, 509–518.

- Arellano, R.O.; Ramon, F.; Rivera, A.; Zampighi, G.A. Calmodulin acts as an intermediary for the effects of calcium on gap junctions from crayfish lateral axons. Membr. Biol. 1988, 101, 119–131.

- Peracchia, C.; Bernardini, G.; Peracchia, L.L. A calmodulin inhibitor prevents gap junction crystallization and electrical uncoupling. Cell Biol. 1981, 91, 124a.

- Peracchia, C.; Bernardini, G.; Peracchia, L.L. Is calmodulin involved in the regulation of gap junction permeability? Arch. 1983, 399,152–154.

- Hertzberg, E.L.; Gilula, N.B. Liver gap junctions and lens fiber junctions: Comparative analysis and calmodulin interaction. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 1981, 46, 639–645.

- Van Eldik, L.J.; Hertzberg, E.L.; Berdan, R.C.; Gilula, N.B. Interaction of calmodulin and other calcium-modulated proteins with mammalian and arthropod junctional membrane proteins. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1985, 126, 825–832.

- Arellano, R.O.; Ramon, F.; Rivera, A.; Zampighi, G.A. Lowering of pH does not directly affect the junctional resistance of crayfish lateral axons. Membr. Biol. 1986, 94, 293–299.

- Benson, A.M. Identification of Innexins Contributing to the Giant-Fiber Escape Response in Marbled Crayfish. Thesis and Dissertations, 1251. httpa://library.illinoisstate.edu/etd/1251, Illinois State University, Normal, IL. 2020.

- Wang, X.G.; Peracchia, C. Positive charges of the initial C-terminus domain of Cx32 inhibit gap junction gating sensitivity to CO2. J. 1997, 73, 798–806.

- Peracchia, C.; Bernardini, G. Gap junction structure and cell-to-cell coupling regulation: Is there a calmodulin involvement? Proc. 1984, 43, 2681–2691.

- Peracchia, C. Communicating junctions and calmodulin: Inhibition of electrical uncoupling in Xenopus embryo by calmidazolium. Membr. Biol. 1984, 81, 49–58.

- Peracchia, C. Calmodulin-like proteins and communicating junctions. Electrical uncoupling of crayfish septate axons is inhibited by the calmodulin inhibitor W7 and is not affected by cyclic nucleotides. Arch. 1987, 408, 379–385.

- Wojtczak, J.A. Electrical uncoupling induced by general anesthetics: A calcium-independent process? In Gap Junctions; Bennett, M.V.L., Spray, D.C., Eds.; Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory: Cold Spring Harbor, NY, USA, 1985; pp. 167–175.

- Tuganowski, W.; Korczynska, I.; Wasik, K.; Piatek, G. Effects of calmidazolium and dibutyryl cyclic AMP on the longitudinal internal resistance in sinus node strips. Arch. 1989, 414, 351–353.

- Gandolfi, S.A.; Duncan, G.; Tomlinson, J.; Maraini, G. Mammalian lens inter-fiber resistance is modulated by calcium and calmodulin. Eye Res. 1990, 9, 533–541.

- Peracchia, C.; Wang, X.; Li, L.; Peracchia, L.L. Inhibition of calmodulin expression prevents low-pH-induced gap junction uncoupling in Xenopus Pflug. Arch. 1996, 431, 379–387.

- Peracchia, C.; Wang, X.G.; Peracchia, L.L. Slow gating of gap junction channels and calmodulin. Membr. Biol. 2000, 178, 55–70.

- Peracchia, C.; Young, K.C.; Wang, X.G.; Peracchia, L.L. Is the voltage gate of connexins CO2-sensitive? Cx45 channels and inhibition of calmodulin expression. Membr. Biol. 2003, 195, 53–62.

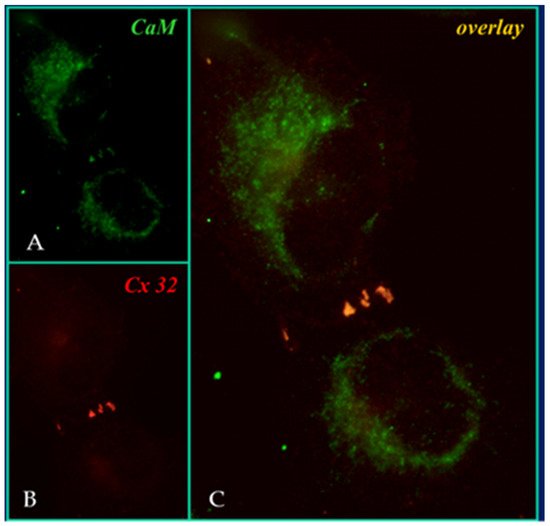

- Peracchia, C.; Sotkis, A.; Wang, X.G.; Peracchia, L.L.; Persechini, A. Calmodulin directly gates gap junction channels. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 26220–26224.

- Sotkis, A.; Wang, X.G.; Yasumura, T.; Peracchia, L.L.; Persechini, A.; Rash, J.E.; Peracchia, C. Calmodulin colocalizes with connexins and plays a direct role in gap junction channel gating. Cell Commun. Adhes. 2001, 8, 277–281.

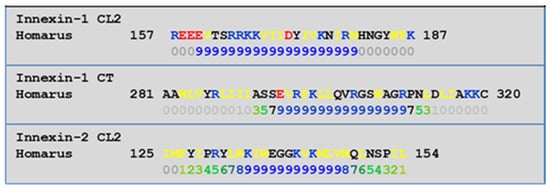

- Kerruth, S.; Coates, C.; Rezavi, S.A.; Peracchia, C.; Torok, K. Ca2+-dependent and -independent interaction of calmodulin with gap junction cytoplasmic loop peptides. 2021, In preparation.

- Kerruth, S.; Coates, C.; Rezavi, S.A.; Peracchia, C.; Torok, K. Calmodulin interaction with gap junction intracellular loop peptides. J. 2018, 114, 468a.

- Dodd, R.; Peracchia, C.; Stolady, D.; Torok, K. Calmodulin association with connexin32-derived peptides suggests trans-domain interaction in chemical gating of gap junction channels. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 26911–26920.

- Torok, K.; Stauffer, K.; Evans, W.H. Connexin 32 of gap junctions contains two cytoplasmic calmodulin-binding domains. J. 1997, 326, 479–483.

- Zou, J.; Salarian, M.; Chen, Y.; Zhuo, Y.; Brown, N.E.; Hepler, J.R.; Yang, J. Direct Visualization of Interaction between Calmodulin and Connexin45. J. 2017, 474, 4035–4051.

- Chen, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Lin, X.; Wong, H.C.; Xu, Q.; Jiang, J.; Wang, S.; Lurtz, M.M.; Louis, C.F.; Veenstra, R.D.; et al. Molecular interaction and functional regulation of connexin50 gap junctions by calmodulin. J. 2011, 435, 711–722.

- Zhou, Y.; Yang, W.; Lurtz, M.M.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, J.; Huang, Y.; Louis, C.F.; Yang, J.J. Calmodulin mediates the Ca2+-dependent regulation of Cx44 gap junctions. J. 2009, 96, 2832–2848.

- Zhou, Y.; Yang, W.; Lurtz, M.M.; Ye, Y.; Huang, Y.; Lee, H.W.; Chen, Y.; Louis, C.F.; Yang, J.J. Identification of the calmodulin binding domain of connexin 43. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 35005–35017.

- Peracchia, C. Direct communication between axons and sheath glial cells in crayfish. Nature 1981, 290, 597–598.

- Saimi, Y.; Kung, C. Calmodulin as an ion channel subunit. Rev. Physiol. 2002, 64, 289–311.

- Kovalevskaya, N.V.; van de Waterbeemd, M.; Bokhovchuk, F.M.; Bate, N.; Bindels, R.J.; Hoenderop, J.G.; Vuister, G.W. Structural analysis of calmodulin binding to ion channels demonstrates the role of its plasticity in regulation. Arch. 2013, 465, 1507–1519.

- Peracchia, ; Girsch, S.J. Calmodulin site at the C-terminus of the putative lens gap junction protein MIP26. Lens Eye Toxic. Res. 1989, 6, 613–621.

- Girsch, S.J.; Peracchia, C. Calmodulin interacts with a C-terminus peptide from the lens membrane protein MIP26. Eye Res. 1991, 10, 839–849.

- Nemeth-Cahalan, K.L.; Hall, J.E. pH and calcium regulate the water permeability of aquaporin 0. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 6777–6782.

- Nemeth-Cahalan, K.L.; Kalman, K.; Hall, J.E. Molecular basis of pH and Ca2+ regulation of aquaporin water permeability. Gen. Physiol. 2004, 123, 573–580.

- Reichow, S.L.; Clemens, D.M.; Freites, J.A.; Nemeth-Cahalan, K.L.; Heyden, M.; Tobias, D.J.; Hall, J.E.; Gonen, T. Allosteric mechanism of water-channel gating by Ca2+-calmodulin. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2013, 20, 1085–1092.

- Fields, J.B.; Nemeth-Cahalan, K.L.; Freites, J.A.; Vorontsova, I.; Hall, J.E.; Tobias, D.J. Calmodulin Gates Aquaporin 0 Permeability through a Positively Charged Cytoplasmic Loop. Biol. Chem. 2016, 292, 185–195.

- Reichow, S.L.; Gonen, T. Noncanonical binding of calmodulin to aquaporin-0: Implications for channel regulation. Structure 2008, 16, 1389–1398.

- Babu, Y.S.; Bugg, C.E.; Cook, W.J. Structure of calmodulin refined at 2.2 A resolution. Mol. Biol. 1988, 204, 191–204.

- Kretsinger, R.H. Hipothesis: Calcium modulated proteins contain EF-hands. In Calcium Transport in Contraction and Secretion; Carafoli, E., Clementi, F., Drabinowski, W., Margreth, A., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1975; pp 469-478.

- Zimmer, D.B.; Green, C.R.; Evans, W.H.; Gilula, N.B. Topological analysis of the major protein in isolated intact rat liver gap junctions and gap junction-derived single membrane structures. Biol. Chem. 1987, 262, 7751–7763.

- Elvira, M.; Villalobo, A. Calmodulin prevents the proteolysis of connexin32 by calpain. Bioenerg. 1997, 42, 207–211.

- Diez, J.A.; Elvira, M.; Villalobo, A. The epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase phosphorylates connexin32. Cell. Biochem. 1998, 187, 201–210.

- Ahmad, S.; Martin, P.E.; Evans, W.H. Assembly of gap junction channels: Mechanism, effects of calmodulin antagonists and identification of connexin oligomerization determinants. J. Biochem. 2001, 268, 4544–4552.

- Peracchia, C. The calmodulin hypoyhesis for gap junction regulation six years later. In Gap Junctions; Hertzberg, E., Johnson, R.G., Eds.; Alan, R. Liss: New York, NY, USA, 1988; Volume 7, pp. 267–282.

- Torok, K.; Trentham, D.R. Mechanism of 2-chloro-(epsilon-amino-Lys75)-[6-[4-(N,N- diethylamino)phenyl]-1,3,5-triazin-4-yl]calmodulin interactions with smooth muscle myosin light chain kinase and derived peptides. Biochemistry 1994, 33, 12807–12820.

- Stauch, K.; Kieken, F.; Sorgen, P. Characterization of the structure and intermolecular interactions between the connexin 32 carboxyl-terminal domain and the protein partners synapse-associated protein 97 and calmodulin. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 27771–27788.

- Sorgen, P.L.; Trease, A.J.; Spagnol, G.; Delmar, M.; Nielsen, M.S. Protein-Protein Interactions with Connexin 43: Regulation and Function. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1428–1449.

- Aseervatham, J.L.X.; Mitchell, C.K.; Lin, Y.-P.; Heidelberg, R.; O’Brian, J. Calmodulin binding to connexin 35: Specializations to function as an electrical synapse. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6346.

- Wei, S.; Cassara, C.; Lin, X.; Veenstra, R.D. Calcium-calmodulin gating of a pH-insensitive isoform of connexin43 gap junctions. J. 2019, 476, 1137–1148.

- Burr, G.S.; Mitchell, C.K.; Keflemariam, Y.J.; Heidelberger, R.; O'Brien, J. Calcium-dependent binding of calmodulin to neuronal gap junction proteins. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005, 335, 1191–1198.

- Siu, R.C.; Smirnova, E.; Brown, C.A.; Zoidl, C.; Spray, D.C.; Donaldson, L.W.; Zoidl, G. Structural and Functional Consequences of Connexin 36 (Cx36) Interaction with Calmodulin. Mol. Neurosci. 2016, 9, 120.

- Gonzalez-Nieto, D.; Gomez-Hernandez, J.M.; Larrosa, B.; Gutierrez, C.; Munoz, M.D.; Fasciani, I.; O’Brien, J.; Zappala, A.; Cicirata, F.; Barrio, L.C. Regulation of neuronal connexin-36 channels by pH. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 17169–17174.

- Li, S.; Hao, B.; Lu, Y.; Yu, P.; Lee, H.C.; Yue, J. Intracellular alkalinization induces cytosolic Ca2+ increases by inhibiting sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA). PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e31905.

- Rose, B.; Rick, R. Intracellular pH, intracellular free Ca, and junctional cell-cell coupling. Membr. Biol. 1978, 44, 377–415.

- Wang, X.G.; Peracchia, C. Connexin 32/38 chimeras suggest a role for the second half of inner loop in gap junction gating by low pH. J. Physiol. 1996, 271, C1743–C1749.

- Wang, X.; Li, L.; Peracchia, L.L.; Peracchia, C. Chimeric evidence for a role of the connexin cytoplasmic loop in gap junction channel gating. Arch. 1996, 431, 844–852.

- Myllykoski, M.; Kuczera, K.; Kursula, P. Complex formation between calmodulin and a peptide from the intracellular loop of the gap junction protein connexin43: Molecular conformation and energetics of binding. Chem. 2009, 144, 130–135.

- Peracchia, C.; Chen, J.T.; Peracchia, L.L. CO(2) sensitivity of voltage gating and gating polarity of gapjunction channels—connexin40 and its COOH-terminus-truncated mutant. Membr. Biol. 2004, 200, 105–113.

- Peracchia, C.; Wang, X.C.; Peracchia, L.L. Behavior of chemical and slow voltage-gates of connexin channels. The cork gating hypothesis. In Gap Junctions—Molecular Basis of Cell Comunication in Health and Disease; Peracchia, C., Ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2000; pp. 271–295.

- Peracchia, C. Calmodulin-cork model of gap junction channel gating—One molecule, two mechanisms. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4938.

- Peracchia, C.; Wang, X.G.; Peracchia, L.L. Is the chemical gate of connexins voltage sensitive? Behavior of Cx32 wild-type and mutant channels. J. Physiol. 1999, 276, C1361–C1373.

- Hu, Z.; Riquelme, M.A.; Wang, B.; Bugay, V.; Brenner, R.; Gu, S.; Jiang, J.X. Cataract-associated Connexin 46 Mutation Alters Its Interaction with Calmodulin and Function of Hemichannels. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 2573–2585.

- Fujimoto, K.; Araki, N.; Ogawa, K.S.; Kondo, S.; Kitaoka, T.; Ogawa, K. Ultracytochemistry of calmodulin binding sites in myocardial cells by staining of frozen thin sections with colloidal gold-labeled calmodulin. Histochem. Cytochem. 1989, 37, 249–256.

- Fleishman, S.J.; Unger, V.M.; Yeager, M.; Ben-Tal, N. A Calpha model for the transmembrane alpha helices of gap junction intercellular channels. Cell 2004, 15, 879–888.

- Perkins, G.; Goodenough, D.; Sosinsky, G. Three-dimensional structure of the gap junction connexon. J. 1997, 72, (2 Pt 1), 533–544.

- Maeda, S.; Nakagawa, S.; Suga, M.; Yamashita, E.; Oshima, A.; Fujiyoshi, Y.; Tsukihara, T. Structure of the connexin 26 gap junction channel at 3.5 A resolution. Nature 2009, 458, 597–602.

- Makowski, L.; Caspar, D.L.; Goodenough, D.A.; Phillips, W.C. Gap Junction Structures: III. The Effect of Variations in the Isolation Procedure. J. 1982, 37, 189–191.

- Makowski, L. In Structural Domains in Gap Junctions: Imnplications for the Control of Intercellular Communication; Gap Junctions, Bennett, M.V.L.S., Spray, D.C., Eds. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratories: Cold Spring Harbor, Long Island, New York. 1985; pp. 5–12.

- Makowski, L.; Caspar, D.L.; Phillips, W.C.; Goodenough, D.A. Gap junction structures. V. Structural chemistry inferred from X-ray diffraction measurements on sucrose accessibility and trypsin susceptibility. Mol. Biol. 1984, 174, 449–481.

- Bukauskas, F.F.; Peracchia, C. Two distinct gating mechanisms in gap junction channels: CO2-sensitive and voltage-sensitive. J. 1997, 72, 2137–2142.

- Peracchia, C.; Salim, M.; Peracchia, L.L. Unusual slow gating of gap junction channels in oocytes expressing connexin32 or its COOH-terminus truncated mutant. Membr. Biol. 2007, 215, 161–168.

- Persechini, A.; Gansz, K.J.; Paresi, R.J. Activation of myosin light chain kinase and nitric oxide synthase activities by engineered calmodulins with duplicated or exchanged EF hand pairs. Biochemistry 1996, 35, 224–228.

- Astegno, A.; La, V. V.; Marino, V.; Dell’Orco, D.; Dominici, P. Biochemical and biophysical characterization of a plant calmodulin: Role of the N- and C-lobes in calcium binding, conformational change, and target interaction. Biophys. Acta. 2016, 1864, 297–307.

- Peracchia, C. Gap junctions. Structural changes after uncoupling procedures. Cell Biol. 1977, 72, 628–641.

- Peracchia, C.; Dulhunty, A.F. Low resistance junctions in crayfish. Structural changes with functional uncoupling. Cell Biol. 1976, 70, pt 1, 419–439.

- Peracchia, C. Low resistance junctions in crayfish. I. Two arrays of globules in junctional membranes. Cell Biol. 1973, 57, 66–76.

- Peracchia, C. Low resistance junctions in crayfish. II. Structural details and further evidence for intercellular channels by freeze-fracture and negative staining. Cell Biol. 1973, 57, 54–65.

- Bukauskas, F.F.; Angele, A.B.; Verselis, V.K.; Bennett, M.V. Coupling asymmetry of heterotypic connexin 45/ connexin 43-EGFP gap junctions: Properties of fast and slow gating mechanisms. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 7113–7118.

- Bernardini, G.; Peracchia, C. Gap junction crystallization in lens fibers after an increase in cell calcium. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1981, 21, 291–299.

- Black, D.J.; Tran, Q.K.; Persechini, A. Monitoring the total available calmodulin concentration in intact cells over the physiological range in free Ca2+. Cell Calcium 2004, 35, 415–425.

- Wu, X.; Bers, D.M. Free and bound intracellular calmodulin measurements in cardiac myocytes. Cell Calcium 2007, 41, 353–364.

- Peracchia, C. Gap junction channelopathies and calmodulinopathies. Do disease-causing calmodulin mutants affect direct cell-cell communication? J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9169.

- Nyegaard, M.; Overgaard, M.T.; Sondergaard, M.T.; Vranas, M.; Behr, E.R.; Hildebrandt, L.L.; Lund, J.; Hedley, P.L.; Camm, A.J.; Wettrell, G.; et al. Mutations in calmodulin cause ventricular tachycardia and sudden cardiac death. J. Hum. Genet. 2012, 91, 703–712.

- Jensen, H.H.; Brohus, M.; Nyegaard, M.; Overgaard, M.T. Human Calmodulin Mutations. Mol. Neurosci. 2018, 11, 396.

- Badone, B.; Ronchi, C.; Kotta, M.C.; Sala, L.; Ghidoni, A.; Crotti, L.; Zaza, A. Calmodulinopathy: Functional Effects of CALM Mutations and Their Relationship With Clinical Phenotypes. Cardiovasc. Med. 2018, 5, 176.

- Kotta, M.C.; Sala, L.; Ghidoni, A.; Badone, B.; Ronchi, C.; Parati, G.; Zaza, A.; Crotti, L. Calmodulinopathy: A Novel, Life-Threatening Clinical Entity Affecting the Young. Cardiovasc. Med. 2018, 5, 175.

- Chazin, W.J.; Johnson, C.N. Calmodulin Mutations Associated with Heart Arrhythmia: A Status Report. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1418.

- Crotti, L.; Spazzolini, C.; Tester, D.J.; Ghidoni, A.; Baruteau, A.E.; Beckmann, B.M.; Behr, E.R.; Bennett, J.S.; Bezzina, C.R.; Bhuiyan, Z.A.; et al. Calmodulin mutations and life-threatening cardiac arrhythmias: Insights from the International Calmodulinopathy Registry. Heart J. 2019, 40, 2964–2975.