Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Margarita Díaz-Guerra and Version 2 by Rita Xu.

Stroke is a relevant cause of death, disability and dementia worldwide. In ischemic stroke, excitotoxicity is the main mechanism of neuronal death in the penumbra area, a potentially recoverable tissue surrounding the irreversibly damaged infarct core. In excitatory neurons, scaffold protein PSD-95 plays a central role in neuronal function but also survival/death choices. Thus, this protein is a promising target for development of neuroprotective strategies for stroke and other pathologies similarly associated to excitotoxicity.

- AVLV-144

- calpain

- cell-penetrating peptides

- excitotoxicity

- ischemia

1. Introduction

Stroke is the second leading cause of death in the world. In 2019, there were 12.2 million incident cases, 101 million prevalent cases and 6.55 million deaths from stroke (11.6% of total deaths) [1]. It is also the leading cause of acquired neurological disability and the second cause of dementia. Thus, stroke represents a significant health issue that, according to demographic changes, is expected to worsen in the future.

Significant progress has been made in stroke management in recent years. Pharmacological therapy for the ischemic type (≈85% of total stroke cases) is still limited to thrombolytic drugs (e.g., tissue plasminogen activator or tPA), which can be only administered in a very short therapeutic window and are contraindicated for hemorrhagic stroke and other frequent medical conditions [2][3][2,3]. Unfortunately, the diagnostic tests able to discriminate the precise stroke type are mainly brain-imaging techniques, not immediately available to all patients. Thus, tPA is only administered to about 10% of patients. Similarly, endovascular thrombectomy, which mechanically restores blood flow, is restricted to some patients [4].

The evidence indicates the importance of developing efficient neuroprotective therapies for stroke treatment. Nevertheless, in the past, a large number of neuroprotective drugs have been tested preclinically and clinically, but none of them have succeed [5]. These failures have raised concern in the field of neuroprotection and shifted the interest to explore delayed mechanisms of stroke (e.g., plasticity, regeneration), or stroke-associated comorbidities, as possible therapeutic targets [6]. However, recent results obtained by the group led by Dr. Tymianski (University of Toronto, Canada) in a Phase 3 clinical trial strongly suggest that early neuroprotection is feasible in patients suffering from acute ischemic stroke (AIS) [7][8][9][7,8,9].

2. Ischemic Stroke and Excitotoxicity

During ischemic stroke, the occlusion of a blood vessel leads to decreased perfusion of a brain area, followed by deprivation of nutrients and oxygen. Two brain areas can be distinguished in the affected brain, the infarct core and the penumbra. While the infarct core contains irreversibly damaged tissue, the penumbra represents an important target for neuroprotective strategies. This area, which only suffers a moderate blood flow reduction, is functionally impaired but remains metabolically active. Thus, the penumbra can be recovered if the blood flow is restored or the cells become more resistant. However, after the primary damage, the penumbra can also suffer processes of secondary neuronal death that cause a gradual expansion of the infarct core. A fundamental mechanism of this delayed form of neuronal death is excitotoxicity, induced by overactivation of the NMDARs.

Dual Roles of NMDARs in Neuronal Survival and Death

This family of glutamate receptors are ligand-gated ion channels highly permeable to Ca2+. In physiological situations, NMDARs are central to neuronal transmission, synaptic plasticity and memory, as well as being central to survival [10]. They are heterotetramers formed by two obligatory GluN1 subunits and two GluN2 (GluN2A–D) or GluN3 (GluN3A–B) subunits, although the most frequently expressed NMDARs contain GluN1 in combination with either GluN2B or GluN2A subunits. The synaptic NMDARs form large and dynamic signaling complexes in the postsynaptic membrane, mostly by interactions established by their intracellular C-terminal domains with signaling, cytoskeleton and scaffold proteins such as PSD-95 [11], which functions as a postsynaptic density (PSD) organizer. Pro-survival signaling initiated by synaptic NMDAR activation and a moderate Ca2+ increase stimulates, among others, antioxidant defenses [12], and activates extracellular signal-regulated kinase [13] and phosphorylation of the cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) [14]. The activation of CREB results in the expression of pro-survival genes such as those encoding brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) [15][16][15,16] or its receptor, tropomyosin-related kinase B (TrkB) [17]. In contrast, activation of NMDARs in pathological conditions—for example, after massive glutamate release in the ischemic brain—opposes these neuroprotective effects and is coupled to cell death pathways [18]. In stroke, deprivation of oxygen and glucose causes an important decrease in ATP levels, followed by membrane depolarization and the release of excitatory neurotransmitters that induce NMDAR overactivation, massive Ca2+-influx and excitotoxicity. Different mechanisms participate in this form of neuronal death, but a major contribution is made by calpain, a Ca2+-dependent protease central to different acute and chronic CNS disorders associated with excitotoxicity [19]. In neurons, calpain processes many different substrates in discreate specific sequences altering their stability, activity or localization [20][21][20,21]. Importantly, some of these calpain substrates are proteins critical to neuronal survival and function, such as the neurotrophin receptor TrkB [22], the GluN2 subunits of the NMDAR [23] or their interacting protein PSD-95 [23][24][23,24].

The dual roles played by NMDARs in neurons have been related to their cellular location, whereas synaptic NMDARs mediate survival signaling pathways, and extrasynaptic receptors activate death pathways. However, another theory states that GluN2A-containing NMDARs are implicated in neuronal survival, while GluN2B-containing NMDARs induce neuronal death [25]. Actually, the “NMDAR location” and “NMDAR subtype” hypotheses are not mutually exclusive since, in the adult cortex, GluN2A and GluN2B subunits are preferentially localized at, respectively, synaptic and extrasynaptic sites. Nevertheless, recent studies have pointed out that the activation of death signaling pathways requires the synergistic activation of both synaptic and extrasynaptic NMDARs [25]. Although we still need a more in depth characterization, our current knowledge about the dual roles of NMDARs in physiopathology has helped to understand previous failure of NMDAR antagonists in stroke clinical trials. This knowledge has also provided solid ground for the development of novel neuroprotective strategies for stroke that are able to inhibit death signaling and downstream NMDAR overactivation, without interfering with survival or, alternatively, strategies aimed at preventing aberrant downregulation of neuronal survival cascades taking place in excitotoxicity. Since PSD-95 plays a central role in neuronal survival and death downstream NMDARs, it has become a very promising target for both types of therapeutic strategies. Such therapies might protect and recover the ischemic penumbra, contributing to reduced stroke damage, but the therapy could be also used to treat other acute and chronic diseases, such as neurodegenerative diseases, which are similarly associated with excitotoxicity [26].

3. PSD-95, a Protein Central to Neuronal Survival and Death

3.1. PSD-95 Structure and Function

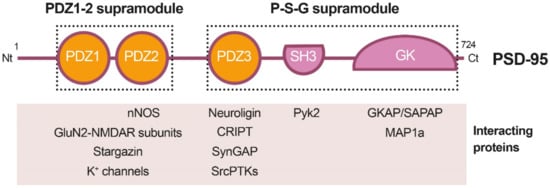

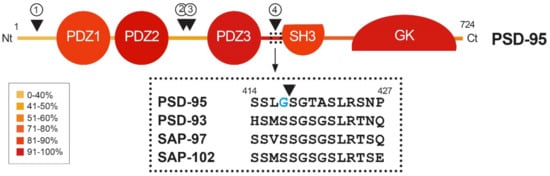

PSD-95 is a member of the Discs large (DLG) family of scaffold proteins, which are a class of the membrane-associated guanylate kinases (MAGUKs), important in cell–cell adhesion and regulation of receptor functioning and clustering [27]. Thus, many of these proteins can interact with the NMDARs through specific protein–protein interaction domains, known as PSD-95/Disc large/Zonula occludens-1 (PDZ) domains. Regarding PSD-95 as a major component of the PSD, it shapes a framework of multiple proteins at excitatory synapses [28] (Figure 1) that organizes signal transduction and is central to glutamatergic synaptic signaling [27]. It is structurally organized in different protein domains (Figure 1) containing, from the N-terminus, three PDZ domains (PDZ1–PDZ3) followed by a Src homology 3 (SH3) domain and a guanylate kinase-like (GK) domain, all of them highly conserved (Figure 2). The PDZ domains interact directly with the C-termini of NMDAR-GluN2 subunits (known as PDZ-ligands or PDZ-binding domains), among others, or they interact indirectly with α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptors (AMPARs) through PDZ-ligands present in AMPAR auxiliary proteins such as stargazin/transmembrane AMPAR regulatory proteins (TARPs). These indirect PDZ interactions, by regulating the content of AMPARs at dendritic spines, are essential for basal synaptic transmission and establishment of long-term potentiation (LTP) [29].

Figure 1. Diagram of PSD-95 protein domains, their organization in supramodules and some examples of their interacting proteins. From the N-terminal (Nt) to the C-terminal (Ct), PSD-95 is constituted by three PDZ (PDZ1 to 3) domains, a Src homology 3 (SH3) domain and a guanylate kinase-like (GK) domain. The PDZ1-2 and P-S-G supramodules, respectively formed by the PDZ1 and PDZ2 tandem or the three other protein domains, are indicated by dotted outlined rectangles.

Recent work has suggested that PSD-95, as well as other related proteins, is functionally and structurally organized in two supramodules that result in a supertertiary structure [30]. The first PSD-95 supramodule contains the PDZ1 and PDZ2 domains, and is known as the PDZ1-2 supramodule (Figure 1). PDZ orientation is restrained in this supramodule but changes to a more flexible conformation, with enhanced binding affinity, upon interaction with PDZ-binding domains of interacting proteins [31]. A very important PDZ1-2 function is the assembly of a ternary complex with the NMDAR-GluN2B subunits and nNOS, established by interaction of the GluN2B PDZ-ligand with PSD-95 PDZ1 or PDZ2, and a noncanonical insertion of a nNOS β-hairpin motif in the binding pocket of PDZ2 [32]. This ternary complex is central to neuronal physiological functions, including plasticity, learning or memory. However, in an excitotoxic context, this complex promotes the coupling of NMDAR overstimulation and Ca2+ influx to nNOS activation and production of nitric oxide (NO), which can react with cell superoxide free radicals, forming oxidant peroxynitrite. This is a highly reactive molecule that produces oxidation of proteins and lipids and generates DNA damage, leading to the activation of apoptotic factors and apoptotic death [33]. In addition to mediating NMDAR-dependent excitotoxicity, NO also negatively regulates the fate of neural stem cells (NSCs) and inhibits regenerative repair after stroke in rat models [34].

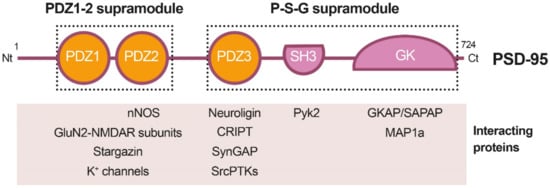

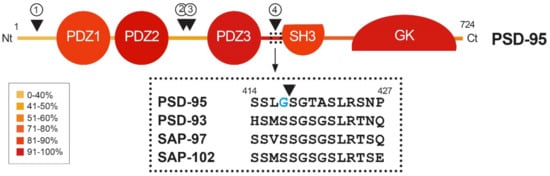

Figure 2. Heatmap showing amino acid conservation inside the different protein domains and interdomain linker sequences of DLG proteins. The location of four calpain-cleavage sites established by Edman sequencing in PSD-95 is also shown (numbered arrowheads). Mice protein sequences of PSD-95, PSD-93, SAP-97 and SAP-102 were compared using Clustal Omega. The percentage of conservation was calculated including identical amino acids and conservative changes, and a color code was assigned to each protein segment. The different DLG domains present a high level of conservation (70–90%), while linkers between them are less conserved, except for the PDZ3–SH3 sequence (94%). Notably, PSD-95 is processed by calpain inside this highly conserved sequence (arrowhead), while other DLG members are not. Substitution of S417 for G417 (blue) inside this highly conserved sequence of PSD-95 might have been determinant for creating a calpain-specific recognition sequence and cleavage of this particular DLG protein in excitotoxic conditions.

Domains PDZ3, SH3 and GK form the second PSD-95 supramodule, known as the P-S-G supramodule, where PDZ3 directly couples with the SH3–GK tandem in a PDZ-ligand binding-dependent manner [35]. Thus, PDZ3 interaction with cysteine-rich PDZ-binding protein (CRIPT) induces a conformational modification of the SH3–GK domain, which influences subsequent formation of PSD-95 homotypic and heterotypic complexes [36][37][36,37], and binding of the heterotrimeric G protein subunit Gnb5 to PSD-95 GK domain at dendritic spines [38]. An additional function of the PDZ3 interaction with CRIPT, a protein that also binds microtubules, is PSD-95 linkage to neuronal cytoskeleton and regulation of dendritic arborization and spine number [39]. Altogether, these results reveal that the organization of the PSD-95 complexes is guided by hierarchical binding mechanisms.

3.2. Regulation of PSD-95 Location and Expression

Given the importance of PSD-95 in PSD formation, and neuronal function and survival, this protein location and expression are highly regulated in neurons. Different posttranslational mechanisms regulate PSD-95 location at the PSD [40]. This protein is associated with the PSD membrane in a perpendicular way through its N-terminus, the C-terminus being oriented to the dendritic spine. A major mechanism regulating this location is the palmytoilation/depalmytoilation of PSD-95 residues C3 and C5, proposed to facilitate the formation and stabilization in development of postsynaptic membrane microdomains that might be central to the organization and function of neuronal synapses [41]. Additional protein modifications such as phosphorylation, ubiquitination, nitrosylation, and neddylation also regulate PSD-95 synaptic stability, protein interactions and function [40][42][40,42].

Concerning PSD-95 levels, this protein increases in normal cortex from early life, reaching maximum levels during adolescence or early adulthood [43], suggesting that this rise might be relevant to synaptic maturation. Moreover, disruption of PSD-95 expression has been associated with synaptic dysfunction in neurodevelopmental disorders such as schizophrenia [44][45][44,45] or autism [46]. Another example of the relevance of PSD-95 levels is the observation that combined knockdown of PSD-95, PSD-93 and SAP-102 reduces synaptic transmission regulated by AMPARs and NMDARs and alters PSD size and structure [47]. Additionally, an acute depletion of PSD-95 levels induces death of hippocampal neurons through activation of an alpha Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (αCaMKII) transduction pathway [48]. Other studies have also shown that a genetic deletion of the GK domain unpredictably inhibits PSD-95 expression. In neurons, PSD-95 forms a ternary protein complex with both the D1 dopamine receptor and NMDARs that limits their direct interaction and dampens reciprocal receptor potentiation. Thus, neurons lacking PSD-95 are more susceptible to NMDAR-mediated excitotoxicity, which causes neuronal damage and neurological impairment [49]. Furthermore, it has been recently demonstrated that PSD-95 protects synapses from ß-amyloid toxicity, suggesting that low levels of synaptic PSD-95 might be a molecular sign indicating synapse vulnerability to Aß in Alzheimer’s disease [50].

3.3. PSD-95 Downregulation in Ischemia Models

A dramatic decrease in PSD-95 levels has been also unveiled as an important pathological mechanism contributing to neuronal death in models of in vitro excitotoxicity, transient ischemia induced in rat by middle cerebral artery occlusion (tMCAO) [23] or permanent ischemia induced by microvascular photothrombosis in mice [24]. PSD-95 downregulation is induced very early after permanent stroke, the complete protein being hardly detectable 2.5 h after injury, and this decrease correlates with the progressive formation of stable protein fragments. Similar PSD-95 fragments are produced in primary cultures of cortical neurons after NMDAR overactivation, while other DLG proteins such as SAP-97 or SAP-102 are not processed in these excitotoxic conditions [24]. The major mechanism responsible for PSD-95 downregulation in excitotoxic neurons is the activation of calpain as a consequence of Ca2+-influx due to NMDAR overactivation (Figure 3B). In fact, PSD-95 is a calpain substrate that is cleaved by this protease in four specific sequences, precisely established by Edman sequencing of protein fragments produced in vitro by digestion with purified enzyme (Figure 2, arrowheads). Interestingly, the four identified cleavage sites are inside interdomain linker sequences that, among the DLG proteins, are generally less conserved than the protein-interaction domains (Figure 2, heatmap). An exception is the PDZ3–SH3 linker, a very flexible sequence described as critical for P-S-G supertertiary structure [30], which presents a very high homology (94%). This sequence mediates a weak and dynamic PDZ3–SH3 association that, as mentioned before, can be reverted by binding of PDZ-ligands to PDZ3 or electrostatic repulsion due to protein phosphorylation. Notably, PSD-95 is processed by calpain between amino acids G417 and S418 inside this highly conserved sequence. Substitution of S417 for G417 in PSD-95 (Figure 2, blue) might have been a determinant for creating a calpain-specific recognition sequence for this particular DLG protein, absent in the other family members. Remarkably, the result of PSD-95 calpain processing induced by excitotoxicity and stroke is the separation of the PDZ1–2 and P-S-G supramodules, together with partial truncation of the latter to uncouple the PDZ3 and the SH3–GK tandem (Figure 3B) [24]. The effects of PSD-95 cleavage on neuronal survival and functioning will be probably derived from rupture of this protein supertertiary structure and production of a set of stable fragments of yet undefined functions.

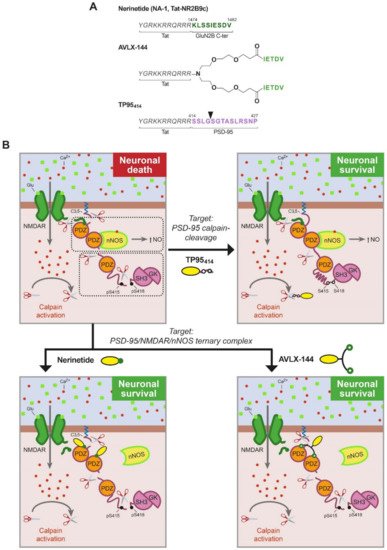

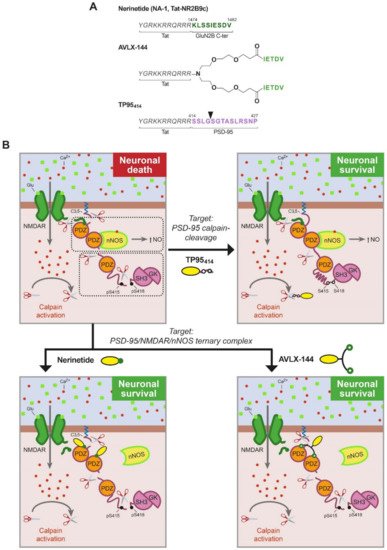

Figure 3. (A). Structure of PSD-95-targeted peptides for stroke treatment. The three peptides share a Tat sequence (aa 47–57, italic). In nerinetide, this sequence is bound to the GluN2B C-terminus (dark green), containing the PDZ ligand, while AVLX-144 is a dimeric peptide with slightly different PDZ ligands (light green) that are more selective towards PDZ1 and PDZ2 over PDZ3. In TP95414, the Tat sequence is followed by a PSD-95 sequence (aa 414–427, purple) containing a calpain-cleavage site (arrowhead). (B). Model of PSD-95 regulation in excitotoxicity and action of PSD-95-targeted peptides. In excitotoxicity, without treatment, PSD-95 contributes to neuronal death by two different mechanisms: first, formation of a trimeric PSD-95–NMDAR–nNOS complex that produces nitric oxide (NO) upon massive calcium influx, and second, processing by calpain of PSD-95 that uncouples the two PSD-95 supramodules (dotted outlined rectangles) and partially cleaves P-S-G. Two different strategies have been developed to prevent these pathological mechanisms by means of brain-permeable neuroprotective peptides. Nerinetide and AVLX-144 are targeted to uncouple the trimeric complex and inhibit NO production while TP95414 prevents PSD-95 cleavage.

References

- Goyal, M.; Menon, B.K.; van Zwam, W.H.; Dippel, D.W.; Mitchell, P.J.; Demchuk, A.M.; Davalos, A.; Majoie, C.B.; van der Lugt, A.; de Miquel, M.A.; et al. Endovascular thrombectomy after large-vessel ischaemic stroke: A meta-analysis of individual patient data from five randomised trials. Lancet 2016, 387, 1723–1731. Valery L Feigin; Benjamin A Stark; Catherine Owens Johnson; Gregory A Roth; Catherine Bisignano; Gdiom Gebreheat Abady; Mitra Abbasifard; Mohsen Abbasi-Kangevari; Foad Abd-Allah; Vida Abedi; et al.Ahmed AbualhasanNiveen Me Abu-RmeilehAbdelrahman I AbushoukOladimeji M AdebayoGina AgarwalPradyumna AgasthiBright Opoku AhinkorahSohail AhmadSepideh AhmadiYusra Ahmed SalihBudi AjiSamaneh AkbarpourRufus Olusola AkinyemiHanadi Al HamadFares AlahdabSheikh Mohammad AlifVahid AlipourSyed Mohamed AljunidSami AlmustanyirRajaa M Al-RaddadiRustam Al-Shahi SalmanNelson Alvis-GuzmanRobert AncuceanuDeanna AnderliniJason A AndersonAdnan AnsarIppazio Cosimo AntonazzoJalal ArablooJohan ÄrnlövKurnia Dwi ArtantiZahra AryanSamaneh AsgariTahira AshrafMohammad AtharAlok AtreyaMarcel AusloosAtif Amin BaigOvidiu Constantin BaltatuMaciej BanachMiguel A BarbozaSuzanne Lyn Barker-ColloTill Winfried BärnighausenMark Thomaz Ugliara BaroneSanjay BasuGholamreza BazmandeganEttore BeghiMahya BeheshtiYannick BéjotArielle Wilder BellDerrick A BennettIsabela M BensenorWoldesellassie Mequanint BezabheYihienew Mequanint BezabihAkshaya Srikanth BhagavathulaPankaj BhardwajKrittika BhattacharyyaAli BijaniBoris BikbovMulugeta M BirhanuArchith BoloorAime BonnyMichael BrauerHermann BrennerDana BryazkaZahid A ButtFlorentino Luciano Caetano dos SantosIsmael R Campos-NonatoCarlos Cantu-BritoJuan J CarreroCarlos A Castañeda-OrjuelaAlberico L CatapanoPromit Ananyo ChakrabortyJaykaran CharanSonali Gajanan ChoudhariEnayet Karim ChowdhuryDinh-Toi ChuSheng-Chia ChungDavid ColozzaVera Marisa CostaSimona CostanzoMichael H CriquiOmid DadrasBaye DagnewXiaochen DaiKoustuv DalalAlbertino Antonio Moura DamascenoEmanuele D'AmicoLalit DandonaRakhi DandonaJiregna Darega GelaKairat DavletovVanessa De la Cruz-GóngoraRupak DesaiDeepak DhamnetiyaSamath Dhamminda DharmaratneMandira Lamichhane DhimalMeghnath DhimalDaniel DiazMartin DichgansKlara DokovaRajkumar DoshiAbdel DouiriBruce B DuncanSahar EftekharzadehMichael EkholuenetaleNevine El NahasIslam Y ElgendyMuhammed ElhadiShaimaa I El-JaafaryMatthias EndresAman Yesuf EndriesDaniel Asfaw ErkuEmerito Jose A FaraonUmar FarooqueFarshad FarzadfarAbdullah Hamid FerozeIrina FilipFlorian FischerDavid FloodMohamed M GadShilpa GaidhaneReza Ghanei GheshlaghAhmad GhashghaeeNermin GhithGhozali GhozaliSherief GhozyAlessandro GialluisiSimona GiampaoliSyed Amir GilaniParamjit Singh GillElena V GnedovskayaMahaveer GolechhaAlessandra C GoulartYuming GuoRajeev GuptaVeer Bala GuptaVivek Kumar GuptaPradip GyanwaliNima Hafezi-NejadSamer HamidiAsif HanifGraeme J HankeyArief HargonoAbdiwahab HashiTreska S HassanHamid Yimam HassenRasmus J HavmoellerSimon I HayKhezar HayatMohamed I HegazyClaudiu HerteliuRamesh HollaSorin HostiucMowafa HousehJunjie HuangAyesha HumayunBing-Fang HwangLicia IacovielloIvo IavicoliSegun Emmanuel IbitoyeOlayinka Stephen IlesanmiIrena M IlicMilena D IlicUsman IqbalSeyed Sina Naghibi IrvaniSheikh Mohammed Shariful IslamNahlah Elkudssiah IsmailHiroyasu IsoGaetano IsolaMasao IwagamiLouis JacobVardhmaan JainSung-In JangSathish Kumar JayapalShubha JayaramRanil JayawardenaPanniyammakal JeemonRavi Prakash JhaWalter D JohnsonJost B JonasNitin JosephJacek Jerzy JozwiakMikk JürissonRizwan KalaniRohollah KalhorYogeshwar KalkondeAshwin KamathZahra KamiabTanuj KanchanHimal KandelAndré KarchPatrick Dmc KatotoGbenga A KayodePedram KeshavarzYousef Saleh KhaderEjaz Ahmad KhanImteyaz A KhanMaseer KhanMoien AB KhanMahalaqua Nazli KhatibJagdish KhubchandaniGyu Ri KimMin Seo KimYun Jin KimAdnan KisaSezer KisaMika KivimäkiDhaval KolteAli KoolivandSindhura Lakshmi Koulmane LaxminarayanaAi KoyanagiKewal KrishanVijay KrishnamoorthyRita V KrishnamurthiG Anil KumarDian KusumaCarlo La VecchiaBen LaceyHassan Mehmood LakTea LallukkaSavita LasradoPablo M LavadosMatilde LeonardiBingyu LiShanshan LiHualiang LinRo-Ting LinXuefeng LiuWarren David LoStefan LorkowskiGiancarlo LucchettiRicardo Lutzky SauteHassan Magdy Abd El RazekFrancesca Giulia MagnaniPreetam Bhalchandra MahajanAzeem MajeedAlaa MakkiReza MalekzadehAhmad Azam MalikNavid ManafiMohammad Ali MansourniaLorenzo Giovanni MantovaniSanti MartiniGiampiero MazzagliaMan Mohan MehndirattaRitesh G MenezesAtte MeretojaAmanual Getnet MershaJunmei Miao JonassonBartosz MiazgowskiTomasz MiazgowskiIrmina Maria MichalekErkin M MirrakhimovYousef MohammadAbdollah Mohammadian-HafshejaniShafiu MohammedAli H MokdadYaser MokhayeriMariam MolokhiaMohammad Ali MoniAhmed Al MontasirRahmatollah MoradzadehLidia MorawskaJakub MorzeWalter MuruetKamarul Imran MusaAhamarshan Jayaraman NagarajanMohsen NaghaviSreenivas Narasimha SwamyBruno Ramos NascimentoRuxandra Irina NegoiSandhya Neupane KandelTrang Huyen NguyenBo NorrvingJean Jacques NoubiapVincent Ebuka NwatahBogdan OanceaOluwakemi Ololade OdukoyaAndrew T OlagunjuHans OrruMayowa O OwolabiJagadish Rao PadubidriAdrian PanaTarang ParekhEun-Cheol ParkFatemeh Pashazadeh KanMona PathakMario F P PeresArokiasamy PerianayagamTruong-Minh PhamMichael A PiradovVivek PodderSuzanne PolinderMaarten J PostmaAkram PourshamsAmir RadfarAlireza RafieiAlberto RaggiFakher RahimVafa Rahimi-MovagharMosiur RahmanMuhammad Aziz RahmanAmir Masoud RahmaniNazanin RajaiPriyanga RanasingheChythra R RaoSowmya J RaoPriya RathiDavid Laith RawafSalman RawafMarissa B ReitsmaVishnu RenjithAndre M N RenzahoAziz RezapourJefferson Antonio Buendia RodriguezLeonardo RoeverMichele RomoliAndrzej RynkiewiczSimona SaccoMasoumeh SadeghiSahar Saeedi MoghaddamAmirhossein SahebkarKm Saif-Ur-RahmanRehab SalahMehrnoosh SamaeiAbdallah M SamyItamar S SantosMilena M Santric-MilicevicNizal SarrafzadeganBrijesh SathianDavide SattinSilvia SchiavolinMarkus P SchlaichMaria Inês SchmidtAletta Elisabeth SchutteSadaf G SepanlouAllen SeylaniFeng ShaSaeed ShahabiMasood Ali ShaikhMohammed ShannawazShajedur Rahman ShawonAziz SheikhSara SheikhbahaeiKenji ShibuyaSoraya SiabaniDiego Augusto Santos SilvaJasvinder A SinghJitendra Kumar SinghValentin Yurievich SkryabinAnna Aleksandrovna SkryabinaBadr Hasan SobaihStefan StorteckySaverio StrangesEyayou Girma TadesseIngan Ukur TariganMohamad-Hani TemsahYvonne TeuschlAmanda G ThriftMarcello TonelliMarcos Roberto Tovani-PaloneBach Xuan TranManjari TripathiGebiyaw Wudie TsegayeAnayat UllahBrigid UnimBhaskaran UnnikrishnanAlireza VakilianSahel Valadan TahbazTommi Juhani VasankariNarayanaswamy VenketasubramanianDominique VervoortBay VoVictor VoloviciKia VosoughiGiang Thu VuLinh Gia VuHatem A WafaYasir WaheedYanzhong WangTissa WijeratneAndrea Sylvia WinklerCharles D A WolfeMark WoodwardJason H WuSarah Wulf HansonXiaoyue XuLalit YadavAli YadollahpourSeyed Hossein Yahyazadeh JabbariKazumasa YamagishiHiroshi YatsuyaNaohiro YonemotoChuanhua YuIsmaeel YunusaMuhammed Shahriar ZamanSojib Bin ZamanMaryam ZamanianRamin ZandAlireza ZandifarMikhail Sergeevich ZastrozhinAnasthasia ZastrozhinaYunquan ZhangZhi-Jiang ZhangChenwen ZhongYves Miel H ZunigaChristopher J L Murray Global, regional, and national burden of stroke and its risk factors, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet Neurology 2021, 20, 795-820, 10.1016/s1474-4422(21)00252-0.

- Prabhakaran, S.; Ruff, I.; Bernstein, R.A. Acute stroke intervention: A systematic review. JAMA 2015, 313, 1451–1462.

- McCarthy, D.J.; Diaz, A.; Sheinberg, D.L.; Snelling, B.; Luther, E.M.; Chen, S.H.; Yavagal, D.R.; Peterson, E.C.; Starke, R.M. Long-term outcomes of mechanical thrombectomy for stroke: A meta-analysis. Sci. World J. 2019, 2019, 1–9.

- Chamorro, A.; Lo, E.H.; Renu, A.; van Leyen, K.; Lyden, P.D. The future of neuroprotection in stroke. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2021, 92, 129–135.

- Roth, S.; Liesz, A. Stroke research at the crossroads—Where are we heading? Swiss Med. Wkly. 2016, 146, w14329.

- Hill, M.D.; Goyal, M.; Menon, B.K.; Nogueira, R.G.; McTaggart, R.A.; Demchuk, A.M.; Poppe, A.Y.; Buck, B.H.; Field, T.S.; Dowlatshahi, D.; et al. Efficacy and safety of nerinetide for the treatment of acute ischaemic stroke (ESCAPE-NA1): A multicentre, double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2020, 395, 878–887.

- Zhou, X.F. ESCAPE-NA1 trial brings hope of neuroprotective drugs for acute ischemic stroke: Highlights of the phase 3 clinical trial on nerinetide. Neurosci. Bull. 2021, 37, 579–581.

- Hankey, G.J. Nerinetide before reperfusion in acute ischaemic stroke: Deja vu or new insights? Lancet 2020, 395, 843–844.

- Wu, Q.; Tymianski, M. Targeting NMDA receptors in stroke: New hope in neuroprotection. Mol. Brain 2018, 11, 15.

- Hardingham, G. NMDA receptor C-terminal signaling in development, plasticity, and disease. F1000 Res. 2019, 8, 1547.

- Papadia, S.; Soriano, F.X.; Leveille, F.; Martel, M.A.; Dakin, K.A.; Hansen, H.H.; Kaindl, A.; Sifringer, M.; Fowler, J.; Stefovska, V.; et al. Synaptic NMDA receptor activity boosts intrinsic antioxidant defenses. Nat. Neurosci. 2008, 11, 476–487.

- Ivanov, A.; Pellegrino, C.; Rama, S.; Dumalska, I.; Salyha, Y.; Ben-Ari, Y.; Medina, I. Opposing role of synaptic and extrasynaptic NMDA receptors in regulation of the extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK) activity in cultured rat hippocampal neurons. J. Physiol. 2006, 572, 789–798.

- Papadia, S.; Stevenson, P.; Hardingham, N.R.; Bading, H.; Hardingham, G.E. Nuclear Ca2+ and the cAMP response element-binding protein family mediate a late phase of activity-dependent neuroprotection. J. Neurosci. 2005, 25, 4279–4287.

- Tao, X.; Finkbeiner, S.; Arnold, D.B.; Shaywitz, A.J.; Greenberg, M.E. Ca2+ influx regulates BDNF transcription by a CREB family transcription factor-dependent mechanism. Neuron 1998, 20, 709–726.

- Lyons, M.R.; Schwarz, C.M.; West, A.E. Members of the myocyte enhancer factor 2 transcription factor family differentially regulate BDNF transcription in response to neuronal depolarization. J. Neurosci. 2012, 32, 12780–12785.

- Deogracias, R.; Espliguero, G.; Iglesias, T.; Rodriguez-Pena, A. Expression of the neurotrophin receptor TrkB is regulated by the cAMP/CREB pathway in neurons. Mol. Cell Neurosci. 2004, 26, 470–480.

- Lai, T.W.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Y.T. Excitotoxicity and stroke: Identifying novel targets for neuroprotection. Prog. Neurobiol. 2014, 115C, 157–188.

- Adamec, E.; Mohan, P.; Vonsattel, J.P.; Nixon, R.A. Calpain activation in neurodegenerative diseases: Confocal immunofluorescence study with antibodies specifically recognizing the active form of calpain 2. Acta Neuropathol. 2002, 104, 92–104.

- Vosler, P.S.; Brennan, C.S.; Chen, J. Calpain-mediated signaling mechanisms in neuronal injury and neurodegeneration. Mol. Neurobiol. 2008, 38, 78–100.

- Ono, Y.; Saido, T.C.; Sorimachi, H. Calpain research for drug discovery: Challenges and potential. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2016, 15, 854–876.

- Vidaurre, O.G.; Gascón, S.; Deogracias, R.; Sobrado, M.; Cuadrado, E.; Montaner, J.; Rodríguez-Peña, A.; Díaz-Guerra, M. Imbalance of neurotrophin receptor isoforms TrkB-FL/TrkB-T1 induces neuronal death in excitotoxicity. Cell Death Dis. 2012, 3, e256.

- Gascon, S.; Sobrado, M.; Roda, J.M.; Rodriguez-Pena, A.; Diaz-Guerra, M. Excitotoxicity and focal cerebral ischemia induce truncation of the NR2A and NR2B subunits of the NMDA receptor and cleavage of the scaffolding protein PSD-95. Mol. Psychiatry 2008, 13, 99–114.

- Ayuso-Dolado, S.; Esteban-Ortega, G.M.; Vidaurre, O.G.; Diaz-Guerra, M. A novel cell-penetrating peptide targeting calpain-cleavage of PSD-95 induced by excitotoxicity improves neurological outcome after stroke. Theranostics 2021, 11, 6746–6765.

- Ge, Y.; Chen, W.; Axerio-Cilies, P.; Wang, Y.T. NMDARs in cell survival and death: Implications in stroke pathogenesis and treatment. Trends Mol. Med. 2020, 26, 533–551.

- Choi, D.W. Glutamate neurotoxicity and diseases of the nervous system. Neuron 1988, 1, 623–634.

- Zhu, J.; Shang, Y.; Zhang, M. Mechanistic basis of MAGUK-organized complexes in synaptic development and signalling. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2016, 17, 209–223.

- Kim, E.; Sheng, M. PDZ domain proteins of synapses. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2004, 5, 771–781.

- Sheng, N.; Bemben, M.A.; Diaz-Alonso, J.; Tao, W.; Shi, Y.S.; Nicoll, R.A. LTP requires postsynaptic PDZ-domain interactions with glutamate receptor/auxiliary protein complexes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 3948–3953.

- Zhang, J.; Lewis, S.M.; Kuhlman, B.; Lee, A.L. Supertertiary structure of the MAGUK core from PSD-95. Structure 2013, 21, 402–413.

- Wang, W.; Weng, J.; Zhang, X.; Liu, M.; Zhang, M. Creating conformational entropy by increasing interdomain mobility in ligand binding regulation: A revisit to N-terminal tandem PDZ domains of PSD-95. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 787–796.

- Christopherson, K.S.; Hillier, B.J.; Lim, W.A.; Bredt, D.S. PSD-95 assembles a ternary complex with the N-methyl-D-aspartic acid receptor and a bivalent neuronal NO synthase PDZ domain. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 27467–27473.

- Picon-Pages, P.; Garcia-Buendia, J.; Munoz, F.J. Functions and dysfunctions of nitric oxide in brain. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2019, 1865, 1949–1967.

- Luo, C.X.; Lin, Y.H.; Qian, X.D.; Tang, Y.; Zhou, H.H.; Jin, X.; Ni, H.Y.; Zhang, F.Y.; Qin, C.; Li, F.; et al. Interaction of nNOS with PSD-95 negatively controls regenerative repair after stroke. J. Neurosci. 2014, 34, 13535–13548.

- Pan, L.; Chen, J.; Yu, J.; Yu, H.; Zhang, M. The structure of the PDZ3-SH3-GuK tandem of ZO-1 protein suggests a supramodular organization of the membrane-associated guanylate kinase (MAGUK) family scaffold protein core. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 40069–40074.

- Rademacher, N.; Kunde, S.A.; Kalscheuer, V.M.; Shoichet, S.A. Synaptic MAGUK multimer formation is mediated by PDZ domains and promoted by ligand binding. Chem. Biol. 2013, 20, 1044–1054.

- Zeng, M.; Ye, F.; Xu, J.; Zhang, M. PDZ ligand binding-induced conformational coupling of the PDZ-SH3-GK tandems in PSD-95 family MAGUKs. J. Mol. Biol. 2018, 430, 69–86.

- Rademacher, N.; Kuropka, B.; Kunde, S.-A.; Wahl, M.C.; Freund, C.; Shoichet, S.A. Intramolecular domain dynamics regulate synaptic MAGUK protein interactions. eLife 2019, 8, e41299.

- Omelchenko, A.; Menon, H.; Donofrio, S.G.; Kumar, G.; Chapman, H.M.; Roshal, J.; Martinez-Montes, E.R.; Wang, T.L.; Spaller, M.R.; Firestein, B.L. Interaction between CRIPT and PSD-95 is required for proper dendritic arborization in hippocampal neurons. Mol. Neurobiol. 2020, 57, 2479–2493.

- Vallejo, D.; Codocedo, J.F.; Inestrosa, N.C. Posttranslational modifications regulate the postsynaptic localization of PSD-95. Mol. Neurobiol. 2017, 54, 1759–1776.

- Tulodziecka, K.; Diaz-Rohrer, B.B.; Farley, M.M.; Chan, R.B.; Di Paolo, G.; Levental, K.R.; Waxham, M.N.; Levental, I. Remodeling of the postsynaptic plasma membrane during neural development. Mol. Biol. Cell 2016, 27, 3480–3489.

- Pedersen, S.W.; Albertsen, L.; Moran, G.E.; Levesque, B.; Pedersen, S.B.; Bartels, L.; Wapenaar, H.; Ye, F.; Zhang, M.; Bowen, M.E.; et al. Site-specific phosphorylation of PSD-95 PDZ domains reveals fine-tuned regulation of protein-protein interactions. ACS Chem. Biol. 2017, 12, 2313–2323.

- Glantz, L.A.; Gilmore, J.H.; Hamer, R.M.; Lieberman, J.A.; Jarskog, L.F. Synaptophysin and postsynaptic density protein 95 in the human prefrontal cortex from mid-gestation into early adulthood. Neuroscience 2007, 149, 582–591.

- Fromer, M.; Pocklington, A.J.; Kavanagh, D.H.; Williams, H.J.; Dwyer, S.; Gormley, P.; Georgieva, L.; Rees, E.; Palta, P.; Ruderfer, D.M.; et al. De novo mutations in schizophrenia implicate synaptic networks. Nature 2014, 506, 179–184.

- Purcell, S.M.; Moran, J.L.; Fromer, M.; Ruderfer, D.; Solovieff, N.; Roussos, P.; O’Dushlaine, C.; Chambert, K.; Bergen, S.E.; Kähler, A.; et al. A polygenic burden of rare disruptive mutations in schizophrenia. Nature 2014, 506, 185–190.

- Coley, A.A.; Gao, W.J. PSD95: A synaptic protein implicated in schizophrenia or autism? Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2018, 82, 187–194.

- Chen, X.; Levy, J.M.; Hou, A.; Winters, C.; Azzam, R.; Sousa, A.A.; Leapman, R.D.; Nicoll, R.A.; Reese, T.S. PSD-95 family MAGUKs are essential for anchoring AMPA and NMDA receptor complexes at the postsynaptic density. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, E6983–E6992.

- Gardoni, F.; Bellone, C.; Viviani, B.; Marinovich, M.; Meli, E.; Pellegrini-Giampietro, D.E.; Cattabeni, F.; Di Luca, M. Lack of PSD-95 drives hippocampal neuronal cell death through activation of an alpha CaMKII transduction pathway. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2002, 16, 777–786.

- Zhang, J.; Xu, T.X.; Hallett, P.J.; Watanabe, M.; Grant, S.G.; Isacson, O.; Yao, W.D. PSD-95 uncouples dopamine-glutamate interaction in the D1/PSD-95/NMDA receptor complex. J. Neurosci. 2009, 29, 2948–2960.

- Dore, K.; Carrico, Z.; Alfonso, S.; Marino, M.; Koymans, K.; Kessels, H.W.; Malinow, R. PSD-95 protects synapses from beta-amyloid. Cell Rep. 2021, 35, 109194.

More