Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Nagabhishek Sirpu Natesh and Version 2 by Jason Zhu.

miRNAs, small non-coding RNAs, have been recently identified as key players regulating cancer pathogenesis. Dysregulated miRNAs are associated with molecular pathways involved in tumor development, metastasis, and chemoresistance in Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), as well as other cancers.

- Pancreatic Cancer

- miR-345

- RNA

1. Pancreatic Cancer

Cancer is one of the leading causes of death globally, acting as a crucial barrier to enhancing life expectancy, with 19.3 million worldwide new cancer incidence accounts and 10 million cancer deaths in 2020 [1]. Pancreatic cancer (PC) is the fourth-highest cause of cancer mortality, with an overall 10-year survival of less than 1% and 5-year survival rate of less than 3%, based on statistics of patients from England and Wales [2][3][2,3]. In 2020, PC accounted for 0.49 million (2.6%) new cases and 0.46 million deaths (4.7%) worldwide [1]. PC accounts for about 3% of all cancers and about 7% of all cancer deaths in the USA [4]. A study of 28 European countries showed that PC would surpass breast cancer as the third leading cause of cancer deaths by 2025 [5].

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) neoplasms that arise from the duct of the exocrine pancreas account for >90% of PCs and contribute to major medical complications. In contrast, PCs that arise from the endocrine gland (pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (NETs)) are less common (<5%). It is estimated that 1 in 64 individuals will develop PDAC, an age-related neoplasm, with an average age at diagnosis of about 71 yrs [6]. With many developed countries facing aging populations, PC incidence level is expected to rise over the coming years and be the second leading cause of death in the US by 2030 [7][8][7,8]. PDAC is an aggressive disease that invades the lungs, liver, peritoneal cavity, lymph nodes, and intestines [9]. Symptoms including abdominal pain, weight loss, bloating, nausea and vomiting, new-onset diabetes, back pain, shoulder pain, pruritus, dyspepsia, lethargy, jaundice, and changes in bowel habits, developed during PDAC, are often neglected by the patients [10].

The modifiable risk factors associated with PC are (i) smoking, with a strong association of 74% increased risk in current smokers and a 20% increased risk in former smokers; (ii) alcohol, with a 15–43% increased risk based on meta-analysis; (iii) obesity, with a 10% increased risk for every 5 BMI units (body mass index); (iv) dietary factors, with a non-significant positive association for red meat and a 17% increased risk associated with 50 g/d of processed meat consumption, compared to 20 g/d; and (v) the presence of Helicobacter pylori, with a 45% increased risk [11]. Several DNA mismatch repair genes, which include MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2, have been reported to be associated with an increased incidence of PDAC [12]. Familial atypical multiple moles-melanoma syndromes (CDKN2A gene mutation), and hereditary pancreatitis (PRSS1 and SPINKI genetic abnormalities) are also associated with an increased risk of PDAC [13][14][13,14]. There is also an immense increased risk of PDAC associated with germline mutation of ovarian and breast cancers (PALB2 and BRCA1/BRCA2, respectively), as alterations in germline BRCA and PALB2 are detected in approximately 5–9% of patients with PDAC and can lead to homologous repair deficiency (HRD) [15].

Although substantial progress has been made in developing many novel cancer therapies, PC survival rates have been static in the last 4 decades, and cytotoxic therapies and their combination with targeted therapies for cancer-associated molecular pathways have not shown adequate results [2]. This is mainly due to (1) the asymptomatic nature of PDAC, (2) lack of specific tumor markers and late-stage diagnosis of the disease, (3) the retroperitoneal position of the pancreas, which limits the imaging capacity to detect this disease at its early stages, (4) PDAC’s high chemotherapy resistance and broad heterogeneity of genetic mutations, (5) a dense stromal environment, (6) rapid upregulation of alternative compensatory pathways, and (7) a majority of patients with unresectable, locally advanced, or metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis [16][17][18][16,17,18], contributing to poor prognosis and dismal surval rates. These factors indicate that if PC is diagnosed earlier, there is a significantly improved chance of disease control with effective treatment [2]. More than two-thirds of PC cases found are associated with diabetes mellitus (DM), linked with increased metastasis in PC patients and an increased inflammatory response, with high glucose levels stimulating PC progression [19]. Previous reports have also shown an increased risk of PC in type 2 DM patients [20].

Current available therapeutic options for PC are surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, immunotherapy, and targeted therapy [21]. Most of the available treatments are palliative, to relieve disease-related symptoms and prolong survival. Recently, targeting major cancer pathways using microRNAs (miRNAs) has shown a potential therapeutic option for cancer treatment due to their ability target more than 200 genes, as reported in theour previous studies [22][23][22,23]. Thus, inhibition (oncomiRs) or replacement (tumor suppressors) of microRNAs is a promising area of study for therapeutics. PC has several challenges, in terms of diagnosis, treatment, and prognostic outlook.

2. PC and miRNA

There is an urgent need to identify novel diagnostic/therapeutic targets for the effective management of highly malignant PC [18]. miRNAs have received significant attention as a new class of non-coding-RNAs engaged in the regulation of gene expression. It is now evident that miRNAs exhibit differential expression in cancer and play essential roles in the disease processes [24]. Biosynthesis of miRNA is a multi-step process, which involves both cytoplasmic and nuclear components. First, RNA polymerase II transcribes miRNA into longer primary transcripts (pri-mRNA) of several hundred kilobases in length. These transcripts have 5′ 7-methyl guanylate (m7G) cap structure and 3′ poly(A) tail, and two mature endonuclease reactions (in the nucleus by Drosha/DGCR8, a ribonuclease III (RNase III) endonuclease that cleaves the pri-miRNA into a 65–70 bp stem-loop precursor miRNA (pre-miRNA)). The pre-miRNA is then transported to the cytoplasm by an exportin-5–RanGTP-dependent mechanism. Further, in the cytoplasm, the pre-miRNA is processed to generate mature 19–24 bp RNA duplex by RNase III endonuclease, Dicer/TRBP, and AGO2. Then, this RNA duplex unwinds and matures to a single-stranded miRNA (one of the strands) by the helicase activity. Further, it enters into the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) and directs the complex to target mRNA, through a poorly defined mechanism. It is extremely rare to have a perfect base pair binding of miRNA and the genes, but a strong base-pairing between the 5′ half of the miRNA (2–8 nucleotides) mediates the mRNA regulation in animals [25]. Any complementarity between the seed region of miRNA and 3′ UTR region of the target gene leads to translation inhibition. Hence, one miRNA is predicted to target more than 200 genes, on average coordinating multiple pathways, and regulating the critical processes of gene activation and suppression. This diverse role leads to the complexity of gene regulation, thus mediating complex cell function networks, such as cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, and organ development [26].

Different patterns have been found in miRNA expression profiles in PC, which have contributed to the development of a miRNAome between the normal and cancerous pancreas [2]. Determination of these miRNA expression profiles has been made possible through different gene profiling methods, mainly microarray, RNA-sequencing, and RT-PCR analysis of specimens [27]. Due to the stability of miRNA in circulation, blood screening could be employed to detect specific miRNA linked with stage, survival rate, or aggressiveness of the disease [28]. Previous studies have demonstrated the potential of miR-483-3p and miR-21 as biomarkers of PDAC from blood plasma. The plasma expression of both miR-483-3p and miR-21 was found to be significantly higher in PDAC patients, compared to healthy controls (p < 0.01), while these miRNA expression levels correlated with overall lower survival in those patients with PDAC (p < 0.01) [29]. Indeed, miR-375 was suggested to be linked with islet cells, as the expression was high in normal pancreatic tissues, compared to the cancerous and inflammatory tissues, with a complete absence in representative cell lines. The serum carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA-19-9) been employed as a marker for assessing clinical treatment efficacy in PC. Limitations associated with CA 19–9 include ineffectiveness, low sensitivity, and specificity, yet it is still the only FDA approved marker in PC [29]. miRNAs that are specific to cancer types can be identified for early screening, and miRNAs could be used for diagnostic purposes, as they are stable in serum, ease the non-invasive detection in circulation, and provide a convenient screening method for miRNA detection. Among the top aberrantly expressed miRNAs in cancer samples, miR-424, miR-100, miR-301, miR-212, and miR-125b-1 were overexpressed, whereas miR-345, miR-142-P, and miR-139 were underexpressed, relative to normal pancreatic samples. Additionally, miR-221, miR-376a, and miR-301 were found to be localized within the tumor cells, rather than other cells in the stroma [30].

The miRNAs miR-141, miR-148a, miR-200a, miR-200b, miR-200c, miR-216, miR-217, and miR-375 exhibited high expression levels, and miR-133a, miR-143, miR-145, and miR-150 exhibited low expression levels within normal pancreatic tissue, compared to 33 other human tissues [31]. Upregulated miR-372, miR-146a, miR-204, miR-10a, and miR-10b were also detected in PC cell lines (CAPAN-1 and CFPAC-1), compared to human normal pancreatic ductal epithelial cells (HPDE), with changes of greater then 10-fold. miR-93, miR-196a, miR-196b, miR-203, miR-205, miR-210, miR-221, miR-222, and miR-224 were upregulated only in cancerous tissues and cell lines. Interestingly, a complete absence of miR-196a and miR-196b was observed in normal and pancreatitis tissues [32]. This gives a potential selectivity to PC. The upregulation of miR-155, miR-203, miR-210, and miR-222, as well as the downregulation of miR-216 and miR-217, are associated with poorer prognosis and overall survival [33]. Among these miRNAs, miR-345 has been gaining attention, due to its involvement in mediating signaling pathways and crosstalk in PDAC and PC, as well as other cancer types. Therefore, the following section will focus on the implications of miR-345 in multiple human malignancies, where PDAC would be given special emphasis.

3. Role of miR-345 in Pancreatic Cancer

miR-345 is a small, non-coding RNA, located at human chromosome 14q32.2, that is reported to have dynamic roles in various human pathologies. Differential expression of miR-345 has been reported in the blood and tissues of multiple human malignancies, such as pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), gastric cancer (GC), colorectal carcinoma (CRC), prostate cancer (PCa), and breast cancer (BRCA) [33]. This differential regulation of miR-345 has been correlated with excessive cell proliferation, invasion, and migration, which are characteristics of cancer development and metastasis. Recent research has gained much attention, implicating the role of miR-345 in various human pathologies [34].

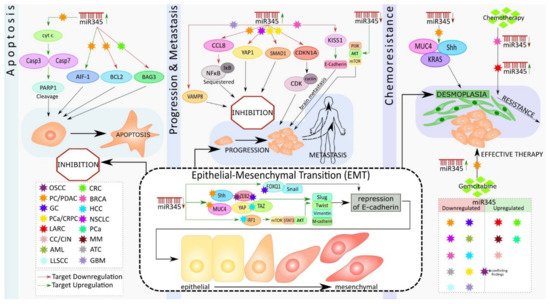

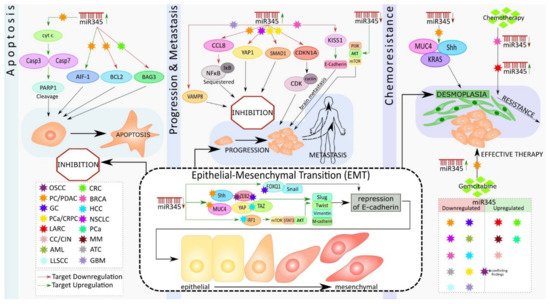

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) is a biological switch that involves the transdifferentiation of epithelial cells attached to the basement membrane and is characterized by apical-basal polarity. Increased mesenchymal phenotypes with spindle-shaped appearance, invasiveness, and enhanced migratory capacity ultimately lead to the demolition of the basement membrane [33]. EMTs occur during various biological processes and are classified into three types: the first type occurs during embryonic development; the second type is associated with adult tissue regeneration; and the third type occurs in cancer progression [35]. Numerous cellular signaling pathways and their crosstalk in the regulation of transcription factors and ultimately trigger EMT in cancer [36]. miR-345 is one the most critical miRNAs that helps to mediate the metastasis signaling pathways of EMT [37]. Studies have found that miR-345 can regulate the upstream and downstream molecules of PI3K/AKT, mTOR, and YAP/TAZ signaling [38][39][40][38,39,40] (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Schematic representation of the role of miR-345 in different cancer types.

Previously, miR-345 was identified as one of the most significantly downregulated miRNAs in PC; however, its functional significance remained unexplored. One study showed that downregulation of miR-345 was a frequent event in PC, and this downregulation significantly correlated with PC progression [41]. Further, ectopic expression of miR-345 in PC cells dramatically reduced cell growth and induced apoptosis [22].

Srivastava et al. showed that miR-345 can induce apoptosis in caspase-dependent and -independent mechanisms in PC cells. They also observed downregulated miR-345 expression in PC tissues and cell lines. They further demonstrated that the overexpression of miR-345 disrupted mitochondrial membrane potential in PC cells, resulting in the release of cytochrome C (Cyt c) to the cytosol from the mitochondria, causing the activation of Caspase 3 and 7 with subsequent cleavage of poly [ADP-ribose] polymerase 1 (PARP-1) (Figure 1). Additionally, overexpressed miR-345 induced the translocation of the apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF-1) to the nucleus, leading to caspase-independent apoptosis. Their experiments identified B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL2), an anti-apoptotic molecule, as the direct target of miR-345. The authors considered the miR-345 downregulation-mediated upregulation of BCL2, the switch that triggered the observed apoptosis resistance in PC [42], (Figure 1).

Apoptosis is a vital tool that assists in biological events, such as tissue homeostasis, tissue development, and immunity. Dysregulation of apoptosis is often associated with tumorigenesis [43]. The primary event in apoptosis is the loss of the mitochondrial membrane potential, which ultimately results in mitochondria-mediated apoptosis [44]. Cyt C is released, in response to the changes in mitochondrial membrane potential, binding with apoptotic protease activating factor-1 (APAF-1) and ATP (adenosine triphosphate), resulting in the formation of a complex. This complex binds to pro-cas-9, which, in turn, causes the cleavage of it and activation of Cas-3 and 7 (effector caspases). Once formed, these effector caspases cleave PARP-1 and mediate caspase-dependent apoptosis [45] (Figure 1). In the case of caspase-independent apoptosis, AIF, from the inter-mitochondrial membrane space, translocates to the nucleus, which results in chromatin condensation, nuclear fragmentation, and, subsequently, cell death [46].

Previous research has shown an increase in the level of BCL2 in numerous cancer types, including PC, and is associated with apoptosis resistance and cancer metastasis [47]. BCL2 regulates the mitochondrial release of Cyt c and AIF, which favor cell survival. Thus, the downregulation of BCL2 by miR-345 holds significance in PC therapy. Tzifi et al. further detail the blockage of the Cyt c release, in response to the overexpression of BCL2, and associated abolishment of apoptosis process [48] (Figure 1).

Srivastava et al. also showed that miR-345 is differentially expressed in PC cell lines, with more downregulated expression in poorly differentiated cancer cells. Ectopic overexpression of miR-345, in two poorly differentiated PC cell lines, Panc1 and MiaPaCa, diminished their growth, clonogenicity, motility, and invasion and enhanced cell–cell interaction. miR-345-overexpressing cells had distinguishable morphological differences and increased epithelial marker (E-cadherin) expression, as well as loss of mesenchymal (N-cadherin, vimentin, twist, slug, and snail) markers expression, as compared to the control cells. Further, the data showed that miR-345 overexpressing PC cells were more sensitive to gemcitabine (GEM), as compared to the control cells. Altogether, these findings demonstrate novel tumor suppressive roles of miR-345 in PC and indicate that miR-345 downregulation may be one of the mechanisms underlying the chemoresistance of PC [42] (Figure 1).

Another study by Mou et al. showed that the downregulated expression of miR-345 in PDAC tissues and cells, and the overexpression of miR-345 in PANC1 and SW1990 cell lines in vitro inhibited proliferation and metastasis by inactivating the nuclear factor κB (NFκB) signaling pathway and further suppressed PC progression [49]. Constitutive activation of NFkB signaling has been reported in approximately 70% of PDAC cases [50]. NFκB is an important transcription factor (TF) that has been widely researched, in the context of inflammation. Constitutive or induced activation of this transcription factor is the key to inflammation-driven carcinogenesis [51]. NFκB operates either by canonical or non-canonical pathways, and the activity of this TF is tightly regulated by the inhibitors of κB (IκB). These inhibitory κB molecules mask the nuclear localization signal (NLS) and thereby sequester the latent NFκB molecule in the cytoplasm [52]. Phosphorylation of IκB molecules by inhibitory κB kinase (IKK), in response to cellular stimuli, results in the ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of IκB, allowing NFκB to enter the nucleus and regulate the target gene expressions associated with cell cycle regulation, proliferation, apoptosis, inflammation, and cancer metastasis [53]. CCL8 (Chemokine C-C motif Ligand 8/MCP2), a cytokine of CC chemokine family, interacts with numerous cell-signaling receptors, regulates and controls leukocyte chemotaxis, and attracts tumor-associated macrophages, inflammatory diseases, and HIV entry [54]. The dynamic role of CCL8 in tumor progression and invasion, by activating NFκB signaling, is widely accepted in different cancer types [55]. CCL8 has been identified as the direct target of miR-345 in PDAC. Further, the overexpression of miR-345 resulted in a low level of CCL8 that, in turn, reduced the nuclear protein level of NFκB and subsequent inhibition of proliferation and migration of PDAC cells. These results suggest that miR-345-5p potentially inhibits PDAC progression by inactivating NFκB signaling [49] (Figure 1).

Restoration of miR-345 in PC cell lines resulted in the inhibition of growth, motility, invasion, and upregulation of epithelial markers [42]. At the molecular level, the ectopic-expression of miR-345 in PC cell lines led to significant downregulation of SHH, MUC4, Kras, C-Myc, CSC, and survival markers, as well as the upregulation of cleaved caspase 7 & 3 and PARP (Figure 1). Sonic hedgehog (Shh) and MUC4 signaling pathways play an essential role in tumor growth and metastasis by promoting EMT, PC stem cells, angiogenesis, and desmoplasia, which limit the delivery and efficacy of chemotherapy [56][57][58][56,57,58]. Therefore, miR-345 is an excellent candidate for diagnostic/prognostic and therapeutic targets in PC.