Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Beata Jastrzebska and Version 2 by Rita Xu.

The retina is a multilayer neuronal tissue located in the back of the eye that transduces the environmental light into a neural impulse. Many eye diseases caused by endogenous or exogenous harm lead to retina degeneration with neuroinflammation being a major hallmark of these pathologies.

- flavonoid

- inflammation

- photoreceptor

- retinitis pigmentosa

1. Introduction

Inflammation is an evolutionarily conserved response by the immune system to harmful stimuli such as pathogens, toxins, and tissue damage [1][2][1,2]. The principal function of inflammation is to localize and minimize the damage to restore tissue homeostasis. A temporary and controlled upregulation of inflammatory mediators occurs during the normal (acute) inflammatory response. Although the inflammatory response is tissue-specific and depends on the nature of the initial stimulus, the common mechanisms involved in inflammatory response include (1) recognition of the detrimental signal by cell surface receptors such as Toll-like receptors (TLRs); (2) activation of intracellular inflammatory pathways, including NF-κB, MAPK, and JAK-STAT pathways; (3) release of inflammatory markers such as cytokines and chemokines; and (4) an increase in the migration of inflammatory cells such as neutrophils and eosinophils. The acute inflammatory response can become chronic under prolonged insult [3][4][5][3,4,5]. Chronic inflammation is a common pathogenic marker of various chronic diseases like cardiovascular disease, diabetes, arthritis, Alzheimer’s disease, cancer, and ocular diseases, including retinitis pigmentosa (RP) among others [6][7][8][6,7,8]. Tissue-resident macrophages are involved in immune defense in addition to other diverse roles they have, such as regulation of metabolic function, clearance of cellular debris, and tissue remodeling [9]. Macrophages can be polarized into different functional phenotypes depending on their origin and tissue microenvironment. Microglial cells are the macrophages resident in the brain and the retina [4][10][4,10]. Microglia function as a checkpoint for the immune system as they express the receptors recognizing the pathogen-associated molecular patterns and harmful factors generated as a consequence of tissue injury [11][12][11,12]. In the retina, microglia have been recognized as a pivotal factor in maintaining eye homeostasis [13]. Upon injury, activated microglia induce a robust response of the innate immune system leading to the production of pro-inflammatory mediators and triggering the activation of adaptive immunity. Although activation of microglia is essential to repair the injured tissue, their uncontrolled inflammatory responses contribute to the severity of many degenerative diseases. Microglia activation is classified into two states: (i) M1, an activated or pro-inflammatory neurotoxic state, characterized by the production of inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukin (IL)-6, and IL-1β; and (ii) M2, an anti-inflammatory or neuroprotective state. The M2 state leads to an increase in the production of some well-characterized markers such as anti-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1 receptor antagonist, IL-4, transforming growth factor (TGF)-β, and IL-10). The M2 state is also associated with an increase in ARG1, an enzyme related to arginine metabolism and wound healing. All these mediators are associated with the decrease of inflammatory cells, an increase in the extracellular matrix protecting proteins for wound repair, and elevation of phagocytosis-associated receptors, such as scavenger receptors [14][15][16][14,15,16].

2. Inflammatory Processes in Retinal Diseases

The transduction of environmental light to neural signals in the brain demands unique metabolic and physiological conditions and is carried out by sensory neurons located in the retina. The retina is a highly organized multilayered tissue, composed of many distinct retinal cell types, which provide essential metabolites, phagocytose waste, and control the homeostasis of the surrounding microenvironment [17]. Three types of resident retinal glial cells such as Mϋller glial cells, astrocytes, and microglia, support the retina’s structural integrity and homeostasis. Mϋller glial, the most common glial cells in the retina, span across the entire thickness of this tissue, while microglia reside in the plexiform layer under normal physiological conditions. However, in pathological conditions, microglia cells migrate to the region of injury and serve as an initial host defense system [17]. Under acute insult, microglia mediate neuroprotection and trigger regenerative processes to preserve retinal health. However, under persistent insults such as inherited mutations, prolonged oxidative stress, or hypoxia, the inflammatory response becomes dysregulated and can aggravate tissue damage [12][18][19][12,18,19]. Thus, the retinal microglia can have a dual function: a beneficial role in the homeostatic state and a detrimental effect in a disease state caused by a chronic pathogenic condition. They provide either neurotrophic support or exacerbate neuroinflammation in response to injury. In the second scenario, several changes occur in the microglia, including changes in these cells’ morphology, function, and up-regulation of the expression and secretion of inflammatory markers. Dysregulated innate immune responses in the eye play an important role in the pathogenesis of retinal degenerative diseases, including age-related macular degeneration (AMD), RP, diabetic retinopathy, and glaucoma [19][20][19,20]. Thus, understanding the mechanisms related to cellular and molecular events in the inflammatory processes and recognizing the specific markers involved in these processes may support the discovery of new therapeutic targets to alleviate the progression of retinal cell death, preventing vision loss.3. Retinitis Pigmentosa

3.1. Epidemiology

Retinitis pigmentosa (RP) is a clinically and genetically heterogeneous hereditary disorder causing progressive retinal degeneration that leads to a decline in vision and eventually blindness (https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/retinitis-pigmentosa/ (accessed on 2 November 2021). Mutations in more than 70 genes expressed predominantly in photoreceptor cells and retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) cells, which are related to phototransduction, retinoid cycle, and maintenance of photoreceptors, can cause RP [21]. These mutations can be inherited as autosomal recessive, autosomal dominant, or X-linked recessive traits. RP is one of the most prevalent retinal degenerative diseases. Over 2 million people in the world and about 100,000 people in the United States suffer from blindness caused by RP (https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/retinitis-pigmentosa/ (accessed on 2 November 2021). Unfortunately, therapeutic options for RP are limited, stressing the need for the development of new treatment strategies to prolong the visual perception in RP patients.

3.2. Pathophysiology

The primary cause of retinal degeneration in RP is the death of rod photoreceptors caused by the conformational aberration in the protein structure due to the genetic change followed by the secondary death of the neighboring cone photoreceptors [22]. Initially, patients experience a decline in dim light vision and loss of peripheral vision. Central vision and consequently daylight vision loss occur at the later stage of the diseases as a result of cone photoreceptor degeneration. Due to the progressive deterioration of photoreceptors, the reorganization of retinal structures that involves phagocytic activity of glial cells is required. During the early onset of degenerative processes in RP, Mϋller glia mediate phagocytosis of declining rods to mitigate retinal damage. These retina resident glial cells do not require migration and are capable of quickly engulfing apoptotic cell bodies in the initial phase of rod photoreceptor degeneration. Eventually, microglial cells become activated either due to signals released from dying rods or crosstalk with Mϋller glia and migrate to the outer retina where they contribute to phagocytic activities [23][24][23,24]. These reactive microglia secrete high levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines that in conjunction with other factors like oxidative stress, unfolded protein response (UPR), and/or changes in the expression of genes involved in cellular metabolism compromise the viability of cone photoreceptors regardless of the genetic impairment [25][26][27][25,26,27]. Despite the increasing knowledge on RP pathogenesis the underlying mechanism of photoreceptor degeneration in RP is not fully understood and requires further comprehensive examination. However, it is known that several cellular and biochemical processes contribute to photoreceptor death. These processes are described below in more detail.

3.2.1. Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Unfolded Protein Response in RP

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is a membranous network responsible for translation, folding, and maturation of newly synthesized proteins before their transport through the Golgi structures to their destination. Aberrant mutations often abrupt the proper folding of the polypeptide chain and lead to the accumulation of misfolded protein within the ER [22][28][22,28]. To restore ER homeostasis in such a scenario the eukaryotic organisms developed an adaptive mechanism called the unfolded protein response (UPR), a collection of signaling pathways that aims to clear the unfolded proteins [28]. Three main signaling proteins that reside in the ER membranes and their related pathways are involved in the UPR, namely IRE1α (inositol-requiring protein-1α), PERK (protein kinase RNA (PKR)-like ER kinase), and ATF6 (activating transcription factor 6) [29][30][29,30]. Under normal physiological conditions, these proteins are inhibited by the residential chaperone binding immunoglobulin protein (BiP). However, under the ER stress caused by the aggregated unfolded proteins, BiP is induced to assist the correct folding. In addition, PERK, IRE1α, and ATF6 become activated, which starts the cascade of signaling reactions to alleviate the over-accumulation of misfolded proteins in the ER by inducing protein degradation mechanisms [28]. Selective activation of IRE1α and ATF6 pathways reduces the levels of multiple misfolding rhodopsin mutants including P23H, T17M, Y178C, C185R, D190G, and K296E without affecting the levels of WT rhodopsin [29][30][29,30]. However, activation of PERK leads to unspecific degradation of both the mutant and WT rhodopsin [30]. Thus, only IRE1α and ATF6, but not PERK pathways, could be targeted in efforts to develop therapeutic strategies against RP.

3.2.2. Oxidative Stress in RP

The retinal tissue is at risk of increased oxidative stress due to the high metabolic rate in the retinal cells required for the efficient signal transduction and metabolite turnover to sustain vision [17]. In such a scenario, a fine balance between the oxidative species and antioxidant mechanisms is necessary to maintain cellular homeostasis. However, in pathological conditions such as RP, the efficiency of the homeostatic mechanisms to counter oxidative stress often declines, disrupting the balance between pro- and antioxidative signaling, leading to excessive oxidative stress, inflammation, and apoptosis [31][32][31,32]. The majority of reactive oxygen species (ROS) with a predominant singlet oxygen superoxide O2− are produced in the mitochondria during respiratory processes. However, the other cellular components, including enzymes located in the ER or plasma membrane also contribute to ROS generation [33][34][33,34]. These metabolic reactions generate the oxidant hydrogen peroxide H2O2, which can facilitate the formation of more toxic-free hydroxyl radical OH֗. Under normal physiological conditions, ROS act as mediators of cellular signaling and are neutralized by the antioxidant defense system, including glutathione (GSH) peroxidase, and superoxide dismutase (SOD) enzymes [35]. However, an imbalance between antioxidant defense mechanisms and ROS production within the cell causes oxidative stress. The excessive free radicals that accumulate within the cell modify the cellular components, including lipids, proteins, and DNA [36]. Thus, oxidative stress is linked to the progression of neurodegenerative diseases, including RP. As mentioned before, in the retina, the oxygen level is high to support the metabolic demands required for signal transduction and quick turnover of the visual chromophore to continuously support the visual processes. During the progressive photoreceptor degeneration in RP, the use of oxygen drops due to decreasing numbers of rod photoreceptors. Consequently, the oxygen level in the retina increases, which enhances the formation of ROS and toxic free radicals. Furthermore, elevated ROS cause oxidative stress to the remaining rods and cones, which accelerates retinal degeneration [37]. ROS also produce detrimental effects on the RPE cells by damaging their lysosomes, which results in a decrease in the RPE phagocytic capacity to degrade the photoreceptor outer segment material [38]. This decrease in the lysosomal activity has been associated with retinal degenerative diseases such as AMD, diabetic retinopathy, and RP [39][40][41][39,40,41]. Oxidative stress has been noted as an important chronic stressor contributing to retinal damage in patients with RP. Indeed, recent studies have discovered that exposure to oxidative stress determines the altered expression of micro-RNA and long non-coding RNA that is likely implicated in the pathogenesis and progression of RP [42].

3.2.3. Inflammation in RP

The retina is a part of the central nervous system (CNS), which translates the image into the electrical neural impulse in the brain. In the retina, the neuroinflammatory response to a pathogen occurs similarly to that in the brain and primarily involves the activation of microglial cells [43][44][43,44]. In addition, the retina-specific Mϋller glial cells are involved in the retinal inflammatory response [23][24][23,24]. In RP, along with the ER stress-mediated activation of the UPR pathways triggered by the aberrant genetic background, the endogenous molecules released from degenerating photoreceptors induce the innate immune cells, resulting in the activation of the inflammatory response. The key players in retinal inflammation are the microglia activated to exert neuroprotection for degenerating photoreceptors [12]. The anti-inflammatory cytokine TGF-β induces a protective effect for deteriorating photoreceptors during the early stage of RP, which is mediated by microglia signaling [45]. However, due to the presence of the abnormal gene, the continuous activation of microglia results in dysregulated expression and secretion of pro-inflammatory markers, which eventually lead to cellular and tissue damage [46][47][46,47]. Indeed, as previously reported, increased levels of several pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-1β and IL-6, and an upsurge in the phagocytic activity of the microglia, were found in vitreal samples obtained from humans affected by RP [48][49][48,49].

To gain a better understanding of the molecular processes that occur in the human retina in RP, studies using animal models are critical. The most common mouse lines used to study pathophysiology in RP are retinal degeneration (rd)1 and rd10 mice that carry nonsense or missense mutation in the β-subunit of cGMP phosphodiesterase gene (Pde6b), respectively [50][51][50,51]. In addition, rat and mouse models that carry a mutation in the Rho gene, especially P23H, are frequently used to study the mechanisms of RP [52][53][54][52,53,54]. The hallmark of rd1 mice is early-onset retinal degeneration with a single layer of photoreceptors left by 4 weeks of age, while rd10 mice display slower retinal degeneration [50][51][50,51]. The microglia infiltration to the retinal photoreceptors layer was observed in rd1 mice at postnatal (P) day 14 and in rd10 mice at P21, indicating their role in the early stages of rod photoreceptor deterioration. A transcriptome profiling study in rd10 mice revealed enhanced expression of cytokines IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α, chemokines CCL3 and CCL5, as well as markers of glial regulatory pathways [55]. In addition, it has been suggested that the retinal Mϋller glial cells guide the migration of the microglia and macrophages to the outer retina to clear dying photoreceptors through the release of cytokines and other inflammatory markers [23][56][23,56]. In fact, in the RP-mimicking retina degeneration induced in rats by N-methyl-N-nitrosourea (MNU), the Mϋller glia enhanced the secretion of Cx3cl1 cytokine, which induced an increase in Cx3cl1 levels in microglia and triggered their migration to the outer retina [57]. Depletion of Cx3cl1-positive microglia in rd10 mice led to changes in phagocytic activities of these cells and the removal of dying photoreceptors [25][58][25,58]. In both rd1 and rd10 mice, uncontrolled secretion of pro-inflammatory chemokines CCL2 and TNF-α by the activated microglia exacerbated the severity of the disease [59]. Moreover, TNF-α induces the NF-κB signaling pathway and leads to upregulation of the NOD-like receptor protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome [60]. An increased level of TNF-α, upregulation of the NF-κB, and NLRP3 expression throughout the retina were also reported in another RP-linked Q344X rhodopsin mouse model [61]. Furthermore, an increase in death signaling molecules such as phosphatidylserine within the membranes of dying rod photoreceptors stimulates phagocytosis and further increases the activation of microglia and macrophages via TLR4. The degeneration of rod photoreceptors in RP is mediated by several death processes, including apoptosis, necrosis, and pyroptosis [62][63][62,63]. The last is activated through the inflammasome NLR protein family, an adaptor protein called apoptosis speck-like protein (ASC), and caspase 1. The canonical inflammasome promotes the activation of the cytokines IL-1β and IL-18, boosting the infiltration of more immune cells to the retina, resulting in the upkeep of the inflammatory state, which ultimately leads to pyroptotic cell death [64]. In addition, cyclooxygenase (COX)-1, an enzyme involved in the synthesis of prostaglandins, which is highly expressed in the microglia, has emerged as a pivotal player in neuroinflammation in the CNS [64]. Upregulation of COX-1 was found in several models of neurodegenerative disorders [65][66][65,66]. As reported, deletion of the Cox-1 gene or pharmacological inhibition of this enzyme significantly reduced inflammation and enhanced survival of photoreceptors in rd10 mice evidenced by the improved visual function in the retina [66]. Moreover, inhibition of the prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) EP2 receptor also delayed photoreceptor degeneration in rd10 mice [66]. Thus, the COX-1/PGE2/EP2 signaling pathway plays a major role in neuroinflammation onset and retina degeneration in rd10 mice. In addition, recent studies indicate that non-ocular systemic inflammatory processes contribute to the progression of retinal degenerative disorders. This observation emerged from a study deciphering the consequences of lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced systemic inflammation performed in the P23H rhodopsin rat model [67]. Systemic injection of LPS into these rats resulted in an enhanced decline in the visual responses, which was associated with increased deterioration of photoreceptor cells. These symptoms were accompanied by an increased number of activated microglia cells and upregulated expression of inflammatory markers and apoptosis-related genes. Thus, chronic exacerbation of the inflammatory response by LPS accelerated the retinal degeneration in the RP-linked P23H rhodopsin rats. These results encourage the pursuit of further in vivo studies evaluating the effect of systemic inflammation in ocular neurodegenerative diseases.

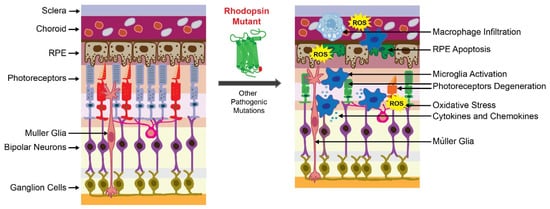

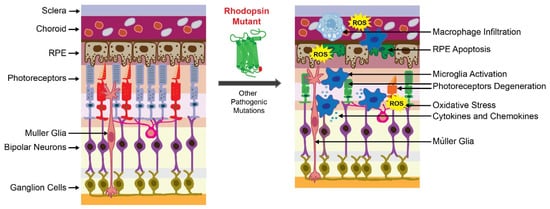

Together, RP pathological upset is related to the activation of the microglia inflammatory response through inflammasome and releasing of inflammatory substances that contribute to the degeneration of rod photoreceptors followed by the death of cone photoreceptors (Figure 1). These degenerative processes lead to the loss of central vision and eventually total blindness. In addition, the progression of retinal degeneration in RP could be accelerated by systemic inflammatory processes.

Figure 1. Retinal degeneration in retinitis pigmentosa (RP). The scheme of the healthy retina is shown on the left. The scheme of the degenerated retina caused by the RP-related mutation is shown on the right. The presence of the mutant receptor triggers degeneration of photoreceptors and retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) cells that are critical for retinal homeostasis. In RP, a genetic insult that causes protein misfolding is associated with the activation of cellular unfolded protein response (UPR) and overproduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS), leading to oxidative stress in the retina. Altogether, these factors activate the inflammatory response orchestrated by microglia and macrophages to clear dying photoreceptors. These immune cells release inflammatory mediators that become dysregulated under persistent insult related to the mutant receptor and increase retinal damage. In addition, mutations in other genes related to phototransduction, retinoid cycle, and maintenance of photoreceptors can cause RP.