iPSC-derived cancer-initiating cells have previously been reported for the establishment of xenograft models that reflect the malignant transformation in PDAC

[32][52][56,71]. Mouse iPSCs from healthy cells have been differentiated in a controlled manner into PDAC progenitor cells

[32][56]. Xenograft models originating from these cells were able to give rise to precancerous lesions, including ADM and PanIN, as well as invasive PDAC. Exploiting a different approach, Kim et al. (2013) hypothesized that a subset of iPSCs induced from human PDAC cells would result in malignant iPSC lines, capable of undergoing early developmental stages of PDAC after engraftment into mice

[34][58]. One of the generated iPSC cell lines carried a

KRASG12D mutation and a deletion of

CDKN2A. The oncogenic

KRAS mutations are the most frequently detected oncogenic alteration in PDAC, being observed in >90% of patients

[53][54][55][72,73,74].

CDKN2A is a tumor suppressor in PDAC and has been described as being inactivated in approximately 50% of patients

[56][57][75,76]. Xenografts originating from the

KRASG12D CDKN2A−\− iPSC cell line gave rise to PanIN-like lesions followed by progression to invasive PDAC

[34][58]. iPSC-based xenograft PDAC models originating from malignant cells demonstrate the potential of iPSCs to provide insights into PDAC onset and progression, including the identification of potential biomarkers for early diagnosis of PDAC. Another application where iPSCs might improve PDAC-modeling is the generation of iPSC-derived organoids containing different cell populations. iPSCs can be committed to a differentiation into the pancreatic exocrine lineage for the generation of acinar and ductal cells and, thus, provide great organoid-modeling possibilities for PDAC

[31][33][58][59][55,57,77,78]. PDAC can develop from both acini and ducts, however knowledge on how these two cells of origin impact cell progression is scarce

[60][79]. Two studies recently assessed how the PDAC oncogenes

KRAS and

GNAS individually affect the growth and progression of PDAC in vitro and in vivo after engraftment of iPSC-derived acinar and ductal organoids in immunocompromised mice

[31][33][55,57]. Both KRAS

G12D-mutated acinar and ductal organoids displayed proliferation in vivo, although the more invasive lesions were generated from acinar organoids. Phenotypically, both oncogenic alterations caused IPMN-like lesions in vivo. Furthermore, PanIN lesions and different stages of PDAC-like tumor formation were observed in xenografts from KRAS

G12D-mutated ductal and acinar organoids. In vitro, KRAS

G12D-mutated ductal organoids displayed epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), which have been suggested to play a role in early tumor formation, metastasis, and chemoresistance in PDAC

[61][62][63][80,81,82]. In contrast, GNAS

R201C/H induced cystic growth in vitro in ductal organoids and to a lesser extend in acinar organoids. These iPSC-derived models provide vital knowledge of the malignant potential of different oncogenes in PDAC. Furthermore, the models provide great opportunities for in-depth assessment of early-stage disease development and progression.

In addition to the above-mentioned applications of iPSCs for disease modeling, iPSCs can also be differentiated into non-malignant cells of the TME. This opens up avenues for the development of complex multicellular models to test therapeutic interventions. For example, TAMs are thought to play an important role in PDAC tumorigenesis and may constitute promising clinical targets

[64][26]. Macrophage models for drug discovery have so far been dependent on a limited source of monocytes derived from PBMCs or animal bone marrow, which has limited the generation of models representative of tissue-resident macrophages (reviewed in

[65][83]). Gutbier and colleagues established a method for controlled large-scale iPSC-derived tissue-resident-resembling macrophages for efficient drug screening and discovery

[66][84]. Genetic manipulation of these iPSC-derived macrophages can be conducted to obtain the desired macrophage subtype. Additionally, cancer-initiating cells originating from iPSCs from healthy cells can also be differentiated into CAFs and vascular endothelial-like cells in vivo

[35][36][37][59,60,61]. Particularly, CAFs have been implicated as important players in the tumorigenesis of PDAC (reviewed in

[67][85])

[68][69][86,87]. CAFs constitute a promising therapeutic target in PDAC and several therapeutic strategies have been investigated preclinically and clinically (reviewed in

[70][71][88,89]). The versatility of iPSCs to generate a variety of cells from the TME can support the development of models that include various cell types

[72][90]. Additionally, the directed differentiation towards a cell line of interest shows the potential of iPSC-derived models for drug screening at the molecular level.

iPSC-based xenografts and organoids provide excellent innovative possibilities for the modeling of PDAC, especially to study precancerous lesions and the development of this disease. Furthermore, the potential of iPSCs as a source for a variety of cells provides an opportunity for the establishment of multicellular models that better represent the PDAC TME. However, iPSC-based PDAC models are still in the early phase and further research is needed to fully exploit their potential.

4. iPSCs as a Cell-Based Immunotherapy

PDAC is characterized by a low mutational burden and, consequently, a low amount of neoantigens are generated for spontaneous antitumor immune responses by the adaptive immune system

[73][22]. Additionally, the highly immunosuppressive TME of PDAC further contributes to its poor immunogenic character. A classical way of stimulating a specific immune response is by antigen vaccination. Therapeutic cancer vaccines aim to stimulate antitumor immunity, e.g., by supporting the activation of cancer-specific CD8

+ and CD4

+ T cells. ESCs have been hypothesized to serve as an efficient source of antigens for cancer vaccines due to their immunogenicity and shared antigenic profile with cancer cells

[74][75][76][91,92,93]. Similar to ESCs, iPSCs have an immunogenic potential and share antigens with PDAC cells, making them an attractive source of antigens for cancer vaccination (reviewed in

[77][94])

[41][44][78][65,68,95]. Kooreman et al. have found that an iPSC-based cancer vaccine was capable of eliciting an immune response towards shared iPSC and cancer cell antigens in murine cancer models

[41][65]. The vaccine consisted of autologous iPSCs to minimize alloimmunity and the toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9) agonist CpG, to enhance the immunostimulatory properties of the vaccine. In murine models of breast, lung, and skin cancer, this iPSC-based cancer vaccine elicited a potent humoral and cell-mediated immune response sufficient to prevent or limit tumor growth in vivo without any observed associated adverse effects

[41][65]. In a mouse model of PDAC, the same vaccine induced protective immunity characterized by the expansion of effector and memory CD8

+ T cells, CD4

+ T cells (excluding T

reg cells), and B cells, while reducing the amount of T

reg cells in tumor-draining lymph nodes

[44][68]. Furthermore, several cancer-signature peptide antigens, containing previously experimentally reported T cell epitopes, were identified in the vaccine in silico; this suggests the possibility for expansion of PDAC antigen-specific effector T cells

[44][68]. This iPSC-based vaccine was proposed as a promising tool to be employed in an adjuvant context, in combination with conventional therapies

[41][65]. Furthermore, this type of vaccination could hold promise in a prophylactic or (neo)adjuvant setting to stimulate the immune system in combination with other immunotherapies, such as immune checkpoint inhibitors, adaptive transfer of primed autologous T cells, chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) cells, or modulators of the immunosuppressive TME, by targeting the WNT-signaling pathway (reviewed in

[79][32])

[80][33].

Prophylactic vaccines can play a role in the prevention of cancers caused by viruses, e.g., human papillomaviruses (HPVs) and the hepatitis B virus (HBV). To date, no prophylactic vaccines aiming at preventing non-viral-related cancers have been approved. Lu et al. (2020) reported an iPSC-based autologous prophylactic cancer vaccination regimen that was evaluated using the KPC mouse model of PDAC with spontaneous tumor development

[43][67]. The PDAC driver mutations Kras

G12D and p53

R172H were introduced in murine iPSCs derived from healthy cells followed by controlled differentiation into PDAC progenitor cells. These cells were antigenically comparable to PDAC cells from the KPC mice and, therefore, serve as a good repertoire of PDAC-expressing antigens. The iPSC-induced PDAC progenitor cells were infected with a non-replicating oncolytic virus to enhance the immunogenicity of the final vaccine formulation. Importantly, the immunogenicity of the vaccine demonstrated a clinical impact by delaying tumor development and prolonging survival of the KPC mice vaccinated before tumor development. However, the vaccine failed to provide complete protection from tumor development in the mice. Upon vaccination, CD8

+ T-cell infiltration increased in the PDAC TME and an accumulation of central memory T cells was observed in the secondary lymph nodes. Furthermore, splenocytes from vaccinated mice, prior to tumor development, showed enhanced production of the proinflammatory cytokine IFNγ after ex-vivo challenge with tumor-cell lines derived from the corresponding model. This iPSC-based autologous prophylactic cancer vaccination regimen demonstrates promising results in a mouse model of PDAC and further studies will clarify whether iPSC-based prophylactic PDAC vaccines have a potential for the prevention of pancreatic malignancies in at-risk individuals.

The first clinical use of iPSC-based cancer vaccines is yet to be seen, but the above-mentioned preclinical studies demonstrate the potential of these vaccines to elicit anti-PDAC immune responses. In addition to PDAC therapy, iPSC-based antitumor vaccination could potentially serve as a promising universal approach in a broad spectrum of cancer types, including mesothelioma, breast cancer, and melanoma (reviewed in

[81][96])

[41][82][83][84][65,97,98,99]. Tumorigenic properties of iPSCs necessitate lethal irradiation of the iPSCs prior to injection into patients to avoid a potential risk of tumor formation (reviewed in

[85][86][100,101])

[41][44][87][88][65,68,102,103]. Additionally, care must be taken to avoid activity of remnant transcription factors used for the induction of the iPSCs (

Figure 1). Three of the four Yamanaka factors, MYC, OCT3/4, and SOX2, are proto-oncogenes and are involved in tumorigenesis

[76][89][90][91][92][93][93,104,105,106,107,108]; these transcription factors have been extensively reviewed elsewhere

[94][95][96][109,110,111]. Efficient screening and purification must be carried out to secure a safe vaccine formulation before clinical implementation.

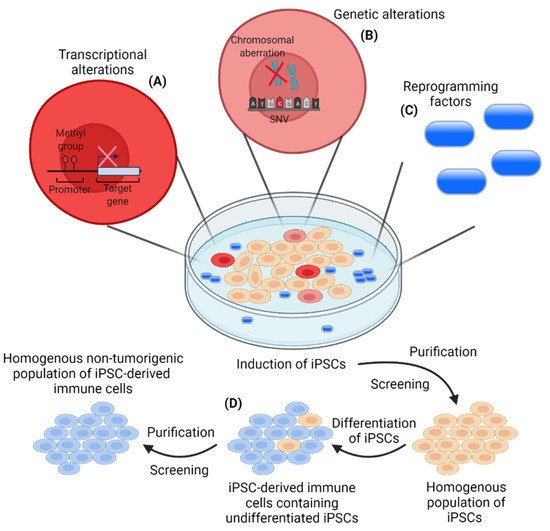

Figure 1. Risks associated with the induction of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) and the generation of a homogenous non-tumorigenic population of iPSC-derived immune cells. (A) Transcriptional alterations (aberrant DNA methylation) can occur in some iPSC clones during the induction of iPSCs leading to clones with a lower differential potential. This heterogenous iPSC induction, due to an improper epigenetic status of some iPSC clones, constitutes a major limitation in the induction of a homogenous population of iPSCs, which should be addressed by optimized reprogramming protocols; (B) Induction of iPSCs includes the risk of genetic alterations by the introduction of single nucleotide variants (SNVs) and/or chromosomal aberrations. The mutation rate has been demonstrated to be around 10 times lower for iPSCs compared to somatic cells. However, genetic alterations will occur and presents an issue in the induction of a homogenous population of iPSCs for further applications. The risk of genetic alterations, influencing the phenotype of a subpopulation of iPSCs, highlights the importance of efficient screening and purification of the induced iPSCs; (C) Induction of iPSCs is carried out with the use of reprogramming factors with a potential tumorigenic potential. This necessitates the efficient removal of the reprogramming factors from the final iPSC population prior to clinical applications; (D) Remnant undifferentiated iPSCs constitute a potential risk for tumor formation in patients. Efficient purification and screening must be conducted to avoid undifferentiated iPSCs in the final population of iPSC-derived immune cells for clinical applications.

5. iPSC-Derived Immune Cells for Cancer Immunotherapies

Current approaches focusing on T cell immunotherapies, such as autologous T cell transfer, engineered T cell receptor (TCR) T cells, and CAR T cells, typically require autologous cell manufacturing for each individual patient. Therefore, there is an unmet need for innovative cell sources to broaden the application of cellular immunotherapies

[97][112]. iPSCs can be a permanent source of various immune cells, which can be genetically modified for optimal therapeutic features. Despite being in the early stages, iPSC-derived NK cells (ClincalTrials.gov, Identifier: NCT03841110) and NKT cells (jrct.niph.go.jp, Trial ID: jRCT2033200116) are currently being clinically investigated in patients with advanced solid tumors. It is worth noting that PDAC patients will be included for monotherapy with the iPSC-derived NK cells or as a combinatorial therapy with immune checkpoint inhibitors. With the increasing availability of promising preclinical data, it is plausible that additional clinical trials will be initiated in the near future. However, before clinical implementation, all safety issues must be thoroughly addressed (discussed in the original paper). Taken together, iPSCs serve as a promising approach for a novel source of a variety of immune cells for adoptive cellular immunotherapies.