Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Bruce Ren and Version 1 by Jia Bao.

Subsequent entrepreneurial intention is a good predictor of serial entrepreneurial endeavors which facilitate the sustainability of economic growth.

- subsequent entrepreneurial intention

- happiness

- family cohesion

1. Introduction

Entrepreneurship promotes the growth of the social economy and provides numerous employment opportunities. Defining entrepreneurial intention—the willingness to engage in venture creation, a link between idea and action—is critical for understanding entrepreneurial activities [1,2][1][2]. It is a predictor of entrepreneurship [2] and a solid antecedent of entrepreneurial behavior that foreshadows the efforts people devote to entrepreneurship [3,4][3][4] and shapes their subsequent behaviors [5]. Accordingly, research on entrepreneurial intention is advancing rapidly [6].

Specifically, the entrepreneurial intentions of entrepreneurs with established firms have attracted scholars’ attention. An intention of continuously engaging in venture creation is formed based on the direct experiences gained from ongoing entrepreneurial activities and related to serial entrepreneurial endeavors. Entrepreneurs who comprehend the difficulty of entrepreneurship have advantages in terms of prompt reactions and can turn their intentions into action. Indeed, the firms of experienced entrepreneurs are equally or more likely to survive than those founded by novices [7]. Therefore, there is a call to elaborate on the entrepreneurial intentions of these experienced entrepreneurs. Unfortunately, for entrepreneurs whose ventures have survived or succeeded, their sustained intention to engage in entrepreneurial activities remains obscure, regardless of its prominent influence in shaping entrepreneurs’ subsequent actions.

Many entrepreneurship scholars [8] have articulated the need for a deeper understanding of the underlying psychological drivers of entrepreneurial intention. Shaver and Scott [9] called for a holistic psychological perspective within entrepreneurial outcomes research involving the person, their representation of the environment, and the cognitive process. Frese and Gielnik [10] emphasized the importance of applying a psychological perspective when studying entrepreneurship and entrepreneurial outcomes. Answering these calls, Lindblom et al. [11] summarized empirical research in order to explain the outcomes of well-being or happiness in entrepreneurship. Some studies [12] found that a low level of well-being was associated with business exit intention, while Hessels et al. [13] demonstrated how depression was positively related to the probability of business exit. Given these findings, happiness as a part of subjective well-being clearly has the potential to influence entrepreneurial intention. Moreover, the cognition gained and emotion experienced during business creation are unique and vital in explaining experienced entrepreneurs’ intentions and behavior given that their nascent counterparts are barely stimulated by real business ventures. As a result, the psychological mechanism, including where entrepreneurs’ happiness comes from and the consequences of this happiness, are a key point in explaining their subsequent entrepreneurial intention (SEI). The performance of firms as an indicator of success reflects the extent to which goals have been achieved, and could influence plans for subsequent action by altering individual psychological states. In addition, this influence on happiness can be affected by some factors from the interpersonal environment, such as family, which have not been studied systematically so far.

2. Subsequent Entrepreneurial Intention

Experienced entrepreneurs have attracted scholars’ attention because compared to nascent entrepreneurs they have unique behaviors and distinctive entrepreneurial outcomes. Their ventures are equally or more likely to survive than firms founded by novice entrepreneurs [7]. Westhead et al. [16][14] indicated that experienced entrepreneurs, particularly serial entrepreneurs (who repeatedly engage in venture creation), are more likely than inexperienced entrepreneurs to have a mindset that seeks to satisfy unmet customer needs. These results illustrate the advantages experienced entrepreneurs possess. Moreover, the contribution of experienced entrepreneurs to entrepreneurial activity is significant [17][15]. In the UK, 19–25% of entrepreneurs are serial [18][16]; in Finland, nearly 30% are [19][17]. However, given the quality and quantity of experienced entrepreneurs, the drivers behind their continuous engagement in entrepreneurial activities are still concealed. Subsequent entrepreneurial intention as the basis for such specific behavior deserves more attention.

A few studies examine the entrepreneurial intention of individuals who have entrepreneurial experience (e.g., ex-entrepreneurs). For example, Hsu [20][18] explained why some entrepreneurs re-enter entrepreneurship after a prior business exit by using a psychological ownership perspective. This study contributed to the understanding of entrepreneurs who quit their ventures and then return to entrepreneurship by investigating their motivation, self-efficacy and other psychological factors. However, few studies focus on the intention of entrepreneurs who are currently running ventures and also have a willingness to create new ventures, as is consistent with the serial/portfolio entrepreneurship phenomenon. This type of entrepreneur, as well as their entrepreneurial intention, is worth more attention because they are an important driver of economic growth [18][16] and are highly valued by venture capitalists [21][19]. In addition, they may have advantages in promptly turning their entrepreneurial intention into actions, which provides a high probability of realizing new venture creations. Thus, the features of this type of entrepreneur and their entrepreneurial intention could contribute to economic growth and the sustainability of entrepreneurship. Surprisingly, there is a lack of examination at present.

Entrepreneurship scholars’ definitions of entrepreneurial intention have a variety of subtle differences. Entrepreneurial intention may be defined as the intention to start a business whenever the opportunity arises, or as the intention to start a specific business. Bird [1] identifies it as the conscious state of mind that directs personal attention, experience, and behavior toward planned entrepreneurial behavior, while Thompson [22][20] characterizes it as the self-acknowledged conviction by a person to set up a new business venture and their conscious plans to do so at some point in the future. Without attempting to resolve these subtle differences, this paper follows Low and MacMillan’s [23][21] definition of entrepreneurship as the “creation of new enterprise” and Ajzen’s [24][22] notion that intentions comprise the willingness of individuals to attempt to enact a given behavior. Given that the central question of this study concerns only the entrepreneurs who are running ventures, the authors regard subsequent entrepreneurial intention as the willingness of existing entrepreneur to continuously start new ventures. The existing research on entrepreneurial intention primarily focuses on would-be entrepreneurs and their initial intention to engage in entrepreneurship, whereas this study emphasizes existing entrepreneurs’ entrepreneurial intention. Therefore, we attempt to use subsequent entrepreneurial intention, which is more specific, to explain the unique phenomenon and distinguish it from the entrepreneurial intention that is generally applied to the initial intention of unexperienced entrepreneurs, while remaining consistent with the core concept of entrepreneurial intention.

Scholars have investigated experienced entrepreneurs’ intentions based on their cognitive styles [18][16], motivations [21][19], and past entrepreneurial experiences [25][23]. For example, Miralles et al. [26][24] shed light on the intention to continue engaging in entrepreneurial activities or exit from a business, indicating that current engagement in entrepreneurship activities alters entrepreneurial intention. Entrepreneurs are not homogenous; some choose to focus on their current venture, whereas others opt to establish additional new ones. Many studies suggest that individual psychological state has a prominent influence on subsequent entrepreneurial intention [20][18]. For instance, Carsrud and Brännback [8] tried to understand the intention to repeat venture-creation activities using behavioral addiction as a psychological factor. These studies provide the rationale for considering the formation of subsequent intention processes through the combination of experiences in engagement (e.g., feedback from current firms) and entrepreneurs’ psychological state (e.g., happiness).

Scholars have focused on firm performance as an antecedent of subsequent intention, testing whether some successful entrepreneurs devote themselves to pursue continuous entrepreneurial activities even when aware of the high rate of failure and uncertainty inherent to the entrepreneurial processes. In this context, certain aspects of entrepreneurs’ cognition—such as self-efficacy [27][25] and the perception of risk [28][26]—offer some insights into the association between performance and subsequent entrepreneurial intention. For example, the overconfidence gained due to high firm performance decreases the perception of risk and makes people engage in more high-risk activities. By altering individual self-efficacy, economic feedback and access to valuable resources have been proven to exert an impact on intentions and behaviors [29][27]. From an economic perspective, successful entrepreneurs have more resources to invest in new ventures to maximize their interests. The assets from an existing firm’s high performance offer opportunities to extend their activity by, for instance, diversifying to decrease risk. On the other hand, prospect theory [30][28] argues that entrepreneurs may show loss aversion when receiving numerous economic rewards, especially given the high risk of loss in entrepreneurial activities. These contradictory explanations reflect how insufficient the understanding of the linkage between firm performance and subsequent entrepreneurial intention remains. Firm performance cannot impact intention until decision-makers interpret and compare it with certain references in order to gain a wide-ranging overview of entrepreneurial activities, which also leaves room for the speculation that some mediating variables, such as entrepreneurial happiness, can play a significant role throughout this relationship. This attempt answers the call for further research regarding antecedents, mediators and moderators required to advance the understanding of entrepreneurial intention [31][29].

3. Entrepreneurs’ Happiness

The psychological antecedents driving entrepreneurs to repeatedly engage in entrepreneurial behaviors are not well understood [8]. Some feelings that arise from engagement in venture-creation activities may have mood-modifying effects on entrepreneurs. These, in turn, may serve as motivators for their continuous entrepreneurial pursuits [8]. This study aims to explain the relationship between current venture performance and entrepreneurial intention to engage in continuous business creations from the perspective of positive psychology, specifically, happiness.

The influence of positive experience on individual cognition and behavior is well-discussed in positive psychology. Hedonic and eudaimonic well-being are two of the included study paradigms. The former asserts that happiness is the ultimate goal of human behavior and the essence of behavioral motivation, and the latter that happiness is based on the realization of individual self-worth [32][30]. In this paper we are not attempting to resolve these subtle differences, given the broad use of well-being and happiness [33][31]. Happiness, as an important component of well-being [34][32], can be defined as “the degree to which an individual judges the overall quality of his or her life as favorable” [35][33]. As an overall cognitive assessment of one’s life [36][34], happiness affects a variety of human behavioral intentions through its psychological effects on affective and cognitive attitudes [37][35]. Some researchers equate happiness to subjective well-being [33][31], i.e., the extent to which an individual is satisfied with their general life circumstances [38][36]. Thus, this study utilizes a general concept of happiness that reflects people’s satisfaction in life. A general evaluation of current life represents a rather comprehensive state and has a greater impact on outcomes compared with a specific feeling. For instance, life satisfaction functions as a better predictor of job performance than job satisfaction [39][37].

There is a common belief that starting a business may be the road to happiness. Entrepreneurs enjoy significantly higher life satisfaction than people in wage employment [40][38], which indicates that happiness is closely related to entrepreneurship [41][39]. Entrepreneurs’ happiness has been studied in terms of how it influences critical investment and continuance decisions [42][40] and persistence [43][41] as well as the venture failure rate resulting from the reduction of efforts and surrender in the face of adversity [44][42]. The existing research suggests that individuals who pursue venture creation may maintain their current business because of the happiness they have gained during the process. For example, one study demonstrated that happiness leads to increased persistence within startup activities [29][27]. Scholars have also emphasized the influence of experienced feelings on entrepreneurial initiative by increasing available psychological resources [45][43]. However, the extent to which entrepreneurs are willing to consistently devote themselves to new business creation rather than focusing on current business is unknown. The neglect of this aspect of entrepreneurial intention comprises a barrier to full understanding of entrepreneurial activities, especially serial entrepreneurial actions. Most relevant studies are associated with business exit and persistence intention [12], and most researchers to date have used students rather than real entrepreneurs as samples when ostensibly investigating the role of entrepreneurial well-being in entrepreneurial outcomes. Furthermore, happiness directly reflects the general life satisfaction that entrepreneurs feel after founding new ventures and helps predict their positive attitude toward the entrepreneurial journey [40][38]; however, there is a lack of specific studies concerning its effects on subsequent intentions, which should be emphasized when regarding entrepreneurship as an individual career path. Moreover, there is an ongoing need to better understand the essential role of well-being as a psychological resource and mechanism in entrepreneurship [46][44], which is consistent with the assertion that few studies examine the role of happiness in entrepreneurship [47][45]. Collectively, these arguments demonstrate the necessity of comprehending entrepreneurs’ happiness when studying existing entrepreneurs’ intention to create more ventures.

The traditional economic rationale cannot sufficiently explain why existing entrepreneurs with good economic feedback still choose to create more new ventures in the face of high failure rate and uncertainty. Interestingly, entrepreneurs’ happiness is strongly influenced by venture performance; Przepiorka [48][46], for example, asserts that entrepreneurial success is related to life satisfaction. This assertion suggests a high probability that current performance relates to entrepreneurial intention by altering the level of happiness. Since entrepreneurial experience affects different feelings (e.g., success brings happiness), this offers a possible venue to examine entrepreneurs’ continuous engagement in entrepreneurship. Our study, from a positive psychology perspective, proposes that happiness play a mediating role in explaining how the feedback from the current venture impacts entrepreneurial intention.

4. Hypothesis Development

4.1. Venture Performance and Happiness

Entrepreneurship is a potential source of well-being [49][47]. A successful venture adds to the entrepreneur’s self-value, income, and wealth. The fulfillment of innate human needs such as the need for competence, accomplishment, and personal growth [50][48], particularly when autonomously chosen, contributes to well-being [38][36]. The pursuit of self-employment is often driven by economic motivations such as the desire for wealth creation [16,51][14][49]. The fulfillment of this goal will lead to happiness, aligning with the view that “good performance makes people happy” [37][35]. This is consistent with Veenhoven’s [52][50] explanation that income helps people meet their needs and therefore relates to well-being.

Similarly, entrepreneurs may feel unhappy and regret their decision to start a business when their financial goals are not satisfied [53][51]. The economic benefits from ventures increase satisfaction with one’s standard of living. Income is a moderately strong predictor of life evaluation [54][52]. A potential reason for this association is that money bestows status and respect upon people. In addition, empirical evidence shows that positive performance enhances entrepreneurs’ confidence in their ability to engage in relevant activities [55][53]. Feelings of competence and confidence in one’s abilities to accomplish important tasks and achieve desired outcomes significantly impact a person’s positive and happy state [56][54].

An increase in wealth does not necessarily enhance happiness, because the entrepreneur’s relative income could fall if their wealth reference group shifts upward; however, increased income is associated with rising happiness [38,57][36][55]. The degree of entrepreneurial satisfaction is influenced mainly by venture performance [58][56], while income correlates with the number of choices, which is in turn associated with stronger happiness [59][57]. Thus, despite the common saying that “money cannot buy happiness,” it seems reasonable that the proof of self-worth, rising level and regularity of income, and increase in personal wealth expected from venture success may collectively contribute to stronger happiness.

As discussed above, good venture performance also indicates the contribution made by entrepreneurs to their community and society. These achievements increase the perceived self-value of entrepreneurs and foster their self-identification as entrepreneurs which is likely to influence many important factors in entrepreneurship such as passion [60][58], promoting happiness in business operations.

In other words, entrepreneurial success is related to individual satisfaction [48][46]. If a firm has better performance, then the entrepreneur’s happiness should rise accordingly. Therefore, we put forth the following hypothesis:

H1:

Firm performance is positively associated with entrepreneurs’ happiness.

4.2. The Moderating Role of Family Cohesion

To fully understand the well-being of entrepreneurs, knowledge of their family lives is required [61][59]. Some scholars even have suggested that “the overall contribution of objective economic status to subjective well-being is nearly trivial” [62][60]. Ravina-Ripoll and his colleagues [63][61] found a link between monetary income and the happiness of entrepreneurs, arguing that the happiest entrepreneurs are not those with the highest level of earnings. According to this assertion, the non-economic factors concerning individual well-being should be enumerated. One of the motivations to become an entrepreneur is to attain the economic rewards that will support a family and enhance its quality of life. Prior research has shown that some individuals devote themselves to an entrepreneurial career because being a business owner allows them more time with their family [64][62]. One way of potentially achieving the desired levels of work–family balance is to become an entrepreneur [65][63]. Thus, family is an important factor to consider when investigating the happiness of entrepreneurs.

A family provides emotional and instrumental support for individuals. A spouse or partner can provide the emotional and instrumental support that contributes to an entrepreneur’s effectiveness [66][64]. Hsu et al. [53][51] suggested the need to examine the role of one’s extended family or other close ties in the cognitive process of entrepreneurs. People can satisfy their needs, such as the need for relatedness (see self-determination theory), and attain a sense of identity from family; entrepreneurs do not need to depend only on their firms to gain happiness. The relationship between firm performance and happiness will thus be weakened when the family acts as an important source of happiness.

Running a firm requires total devotion to entrepreneurial activities. This responsibility tends to cause concerns about family–work balance, whereby work–family conflict often becomes more intensive in the entrepreneurial context [67][65]. Some have argued that individuals who seek wealth creation [68,69][66][67] consider entrepreneurship a path to achieve this goal. Once their goals are reached, individuals feel a sense of happiness. However, good firm performance may not necessarily guarantee a high level of happiness. From a supply and demand view, running a successful venture and maintaining a good family relationship often compete for entrepreneurs’ mental resources. A good relationship with their family makes entrepreneurs value family members’ feelings, necessitating that they spend time and resources on them. Moreover, a high level of performance implies that entrepreneurs have dedicated a huge effort and vast mental resources to their venture. Thus, entrepreneurs who are in good relationships may feel guilty because high firm performance comes at the cost of family. They are obligated to spend more on their family, so the happiness performance offers them is not as important as it is for their counterparts who are in low-quality family relationships. In other words, the association between performance and entrepreneurs’ happiness varies according to different family conditions. Specifically, when entrepreneurs have good relationships with family members, the positive effect of performance on their happiness will decrease.

Olson et al. [70][68] defined family cohesion as the “emotional bonding that family members have toward one another”. Thus, a cohesive family is more likely to provide instrumental and emotional support [71[69][70],72], which alleviates the happiness-reducing stress firms bring to individuals. This finding is plausible considering the buffering effect that family cohesion can offer. We speculate that family cohesion will act as a buffer in the positive effect of a venture on happiness, producing the following hypothesis:

H2:

Family cohesion negatively moderates the positive relationship between firm performance and entrepreneurs’ happiness.

4.3. The Mediating Role of Happiness

This study contends that firm performance influences subsequent entrepreneurial intention through entrepreneurs’ happiness. The emphasis is on the entrepreneurial intention of individuals who are running business to engage in the creation of new ventures. Entrepreneurs can receive performance feedback and gain feelings such as happiness from their business, which would-be entrepreneurs cannot. This leaves room for the investigation of happiness experienced during entrepreneurial activities as a mediator in the formation of subsequent intention. Two requirements must be met to demonstrate this. The first is that there is a linkage between firm performance and happiness. The other is that happiness should be associated with SEI. We argue that entrepreneurs must first perceive a positive overall cognitive assessment of their current situation. Without such a positive overall assessment, SEI is less likely to be formed. In other words, happiness mediates the relationship between firm performance and subsequent entrepreneurial intentions.

This study therefore hypothesizes a direct link between happiness and SEI. There is significant evidence for the relationship between happiness and entrepreneurial intention. For instance, researchers [12] found that poor well-being increases exit likelihood. Some scholars have suggested that job satisfaction has a significant negative direct impact on intention to quit [73][71]. Our study does not focus on job satisfaction; however, certain studies related to job satisfaction support our hypothesis. Multiple studies have provided empirical support to the proposition that entrepreneurs with better well-being are more likely to persist in their endeavors [61][59]. High levels of well-being can enhance psychological resources such as resilience and self-esteem, fostering continued perseverance through challenging tasks [41][39]. In addition, positive feelings send signals to an individual that their efforts lead to their success, which encourages continued proactivity [41][39] and tie an individual closer to their work as entrepreneurs, resulting in enhanced dedication [74][72]. Performance accomplishments are a more powerful form of experience than indirect experience in shaping future behavior. However, only a few studies have focused primarily on this type of entrepreneurial experience, and scholars have just begun to assess its impact on entrepreneurial intention [75][73]. Entrepreneurs with less happiness are more likely to close their businesses even when their firms are profitable [76][74]. One study implied that resources result in confidence and happiness [29][27] and highlighted how well-being can be an important mediating variable concerning entrepreneurial activity. Thus, happiness could play a mediating role in the relationship between performance and subsequent entrepreneurial intention. Happiness serves as a positive overall psychological cognitive factor shaped by firm performance, and can push entrepreneurs toward the formation of subsequent entrepreneurial intention. Therefore, we offer the following hypothesis:

H3:

Entrepreneurs’ happiness mediates the relationship between firm performance and subsequent entrepreneurial intention.

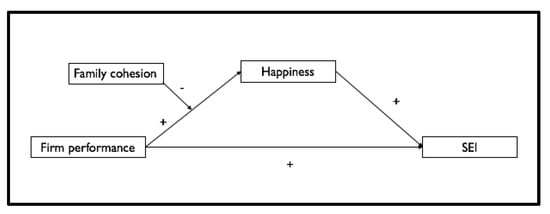

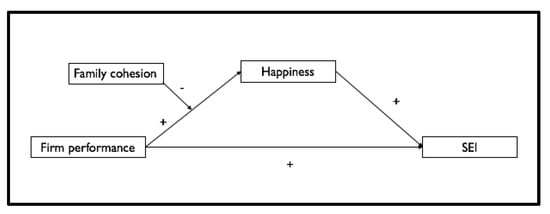

These proposed relationships are shown in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1. The Mediated Moderation Model. SEI = subsequent entrepreneurial intention.

References

- Bird, B. Implementing Entrepreneurial Ideas: The Case for Intention. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1988, 13, 442.

- Krueger, N.F.; Carsrud, A.L. Entrepreneurial Intentions: Applying the Theory of Planned Behaviour. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 1993, 5, 315–330.

- Kautonen, T.; van Gelderen, M.; Fink, M. Robustness of the Theory of Planned Behavior in Predicting Entrepreneurial Intentions and Actions. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2015, 39, 655–674.

- van Gelderen, M.; Kautonen, T.; Wincent, J.; Biniari, M. Implementation Intentions in the Entrepreneurial Process: Concept, Empirical Findings, and Research Agenda. Small Bus. Econ. 2018, 51, 923–941.

- Ajzen, I. Nature and Operation of Attitudes. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 27–58.

- Liñán, F.; Fayolle, A. A Systematic Literature Review on Entrepreneurial Intentions: Citation, Thematic Analyses, and Research Agenda. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2015, 11, 907–933.

- Headd, B. Redefining Business Success: Distinguishing between Closure and Failure. Small Bus. Econ. 2003, 21, 51–61.

- Carsrud, A.; Brännback, M. Entrepreneurial Motivations: What Do We Still Need to Know? J. Small Bus. Manag. 2011, 49, 9–26.

- Shaver, K.G.; Scott, L.R. Person, Process, Choice: The Psychology of New Venture Creation. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1992, 16, 23–46.

- Frese, M.; Gielnik, M.M. The Psychology of Entrepreneurship. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2014, 1, 413–438.

- Lindblom, A.; Lindblom, T.; Wechtler, H. Dispositional Optimism, Entrepreneurial Success and Exit Intentions: The Mediating Effects of Life Satisfaction. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 120, 230–240.

- Peel, D.; Berry, H.L.; Schirmer, J. Farm Exit Intention and Wellbeing: A Study of Australian Farmers. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 47, 41–51.

- Hessels, J.; Rietveld, C.A.; Thurik, A.R.; Van der Zwan, P. Depression and Entrepreneurial Exit. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 32, 323–339.

- Westhead, P.; Ucbasaran, D.; Wright, M. Decisions, Actions, and Performance: Do Novice, Serial, and Portfolio Entrepreneurs Differ? J. Small Bus. Manag. 2005, 43, 393–417.

- Plehn-Dujowich, J. A Theory of Serial Entrepreneurship. Small Bus. Econ. 2010, 35, 377–398.

- Westhead, P.; Ucbasaran, D.; Wright, M.; Binks, M. Novice, Serial and Portfolio Entrepreneur Behaviour and Contributions. Small Bus. Econ. 2005, 25, 109–132.

- Hyytinen, A.; Ilmakunnas, P. What Distinguishes a Serial Entrepreneur? Ind. Corp. Chang. 2007, 16, 793–821.

- Hsu, D.K. ‘This Is My Venture!’ The Effect of Psychological Ownership on Intention to Reenter Entrepreneurship. J. Small Bus. Entrep. 2013, 26, 387–402.

- Westhead, P.; Wright, M. Novice, Portfolio, and Serial Founders: Are They Different? J. Bus. Ventur. 1998, 13, 173–204.

- Thompson, E.R. Individual Entrepreneurial Intent: Construct Clarification and Development of an Internationally Reliable Metric. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2009, 33, 669–694.

- Low, M.B.; MacMillan, I.C. Entrepreneurship: Past Research and Future Challenges. J. Manag. 1988, 14, 139–161.

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Processes 1991, 50, 179–211.

- Baron, R.A.; Ensley, M.D. Opportunity Recognition as the Detection of Meaningful Patterns: Evidence from Comparisons of Novice and Experienced Entrepreneurs. Manag. Sci. 2006, 52, 1331–1344.

- Miralles, F.; Giones, F.; Gozun, B. Does Direct Experience Matter? Examining the Consequences of Current Entrepreneurial Behavior on Entrepreneurial Intention. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2017, 13, 881–903.

- McGee, J.E.; Peterson, M.; Mueller, S.L.; Sequeira, J.M. Entrepreneurial Self–Efficacy: Refining the Measure. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2009, 33, 965–988.

- Segal, G.; Borgia, D.; Schoenfeld, J. The Motivation to Become an Entrepreneur. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2005, 11, 42–57.

- Marshall, D.R.; Gigliotti, R. Bound for Entrepreneurship? A Career-Theoretical Perspective on Entrepreneurial Intentions. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2020, 16, 287–303.

- Tversky, A. Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. Science 1974, 185, 1124–1131.

- Fayolle, A.; Liñán, F. The Future of Research on Entrepreneurial Intentions. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 663–666.

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivations: Classic Definitions and New Directions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2000, 25, 54–67.

- Kong, F.; Zhao, J.; You, X. Emotional Intelligence and Life Satisfaction in Chinese University Students: The Mediating Role of Self-Esteem and Social Support. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2012, 53, 1039–1043.

- Naudé, W.; Amorós, J.E.; Cristi, O. “Surfeiting, the Appetite May Sicken”: Entrepreneurship and the Happiness of Nations. Small Bus. Econ. 2014, 42, 523–540.

- Blanchflower, D.G.; Oswald, A.J. Money, Sex and Happiness: An Empirical Study. Scand. J. Econ. 2004, 106, 393–415.

- Howell, R.T.; Howell, C.J. The Relation of Economic Status to Subjective Well-Being in Developing Countries: A Meta-Analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2008, 134, 536–560.

- Lyubomirsky, S.; King, L.; Diener, E. The Benefits of Frequent Positive Affect: Does Happiness Lead to Success? Psychol. Bull. 2005, 131, 803–855.

- Diener, E.; Suh, E.M.; Lucas, R.E.; Smith, H.L. Subjective Weil-Being: Three Decades of Progress. Psychol. Bull. 1999, 125, 276–302.

- Erdogan, B.; Bauer, T.N.; Truxillo, D.M.; Mansfield, L.R. Whistle While You Work: A Review of the Life Satisfaction Literature. J. Manag. 2012, 38, 1038–1083.

- Binder, M.; Coad, A. Life Satisfaction and Self-Employment: A Matching Approach. Small Bus. Econ. 2013, 40, 1009–1033.

- Foo, M.-D.; Uy, M.A.; Baron, R.A. How Do Feelings Influence Effort? An Empirical Study of Entrepreneurs’ Affect and Venture Effort. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 1086–1094.

- Cooper, A.C.; Artz, K.W. Determinants of Satisfaction for Entrepreneurs. J. Bus. Ventur. 1995, 10, 439–457.

- Collins, C.J.; Hanges, P.J.; Locke, E.A. The Relationship of Achievement Motivation to Entrepreneurial Behavior: A Meta-Analysis. Hum. Perform. 2004, 17, 95–117.

- Rocha, V.; Praag, M. Mind the Gap: The Role of Gender in Entrepreneurial Career Choice and Social Influence by Founders. Strateg. Manag. J. 2020, 41, 841–866.

- Hahn, V.C.; Frese, M.; Binnewies, C.; Schmitt, A. Happy and Proactive? The Role of Hedonic and Eudaimonic Well–Being in Business Owners’ Personal Initiative. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2012, 36, 97–114.

- Wiklund, J.; Nikolaev, B.; Shir, N.; Foo, M.-D.; Bradley, S. Entrepreneurship and Well-Being: Past, Present, and Future. J. Bus. Ventur. 2019, 34, 579–588.

- McGowan, P.; Redeker, C.L.; Cooper, S.Y.; Greenan, K. Female Entrepreneurship and the Management of Business and Domestic Roles: Motivations, Expectations and Realities. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2012, 24, 53–72.

- Przepiorka, A.M. Psychological Determinants of Entrepreneurial Success and Life-Satisfaction. Curr. Psychol. 2017, 36, 304–315.

- Stephan, U. Entrepreneurs’ Mental Health and Well-Being: A Review and Research Agenda. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 32, 290–322.

- Locke, E.A.; Latham, G.P. Building a Practically Useful Theory of Goal Setting and Task Motivation: A 35-Year Odyssey. Am. Psychol. 2002, 57, 705–717.

- Shinnar, R.S.; Young, C.A. Hispanic Immigrant Entrepreneurs in the Las Vegas Metropolitan Area: Motivations for Entry into and Outcomes of Self-Employment. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2008, 46, 242–262.

- Veenhoven, R. Is Happiness Relative? Soc. Indic. Res. 1991, 24, 1–34.

- Hsu, D.K.; Burmeister-Lamp, K.; Simmons, S.A.; Foo, M.-D.; Hong, M.C.; Pipes, J.D. “I Know I Can, but I Don’t Fit”: Perceived Fit, Self-Efficacy, and Entrepreneurial Intention. J. Bus. Ventur. 2019, 34, 311–326.

- Diener, E.; Ng, W.; Harter, J.; Arora, R. Wealth and Happiness across the World: Material Prosperity Predicts Life Evaluation, Whereas Psychosocial Prosperity Predicts Positive Feeling. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 99, 52–61.

- Hsu, D.K.; Wiklund, J.; Cotton, R.D. Success, Failure, and Entrepreneurial Reentry: An Experimental Assessment of the Veracity of Self–Efficacy and Prospect Theory. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2017, 41, 19–47.

- Caprara, G.V.; Steca, P.; Gerbino, M.; Paciello, M.; Vecchio, G.M. Looking for Adolescents’ Well-Being: Self-Efficacy Beliefs as Determinants of Positive Thinking and Happiness. Epidemiol. Psichiatr. Soc. 2006, 15, 30–43.

- Cummins, R.A. Personal Income and Subjective Well-being: A Review. J. Happiness Stud. 2000, 1, 133–158.

- Carree, M.A.; Verheul, I. What Makes Entrepreneurs Happy? Determinants of Satisfaction Among Founders. J. Happiness Stud. 2012, 13, 371–387.

- Diener, E.; Seligman, M.E.P. Toward an Economy of Well-Being. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 2004, 5, 31.

- Cardon, M.S.; Wincent, J.; Singh, J.; Drnovsek, M. The Nature and Experience of Entrepreneurial Passion. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2009, 34, 511–532.

- Ryff, C.D. Entrepreneurship and Eudaimonic Well-Being: Five Venues for New Science. J. Bus. Ventur. 2019, 34, 646–663.

- Smith, D.M.; Langa, K.M.; Kabeto, M.U.; Ubel, P.A. Health, Wealth, and Happiness: Financial Resources Buffer Subjective Well-Being After the Onset of a Disability. Psychol. Sci. 2005, 16, 663–666.

- Ravina-Ripoll, R.; Ahumada-Tello, E.; Evans, R.D.; Foncubierta-Rodriguez, M.J.; Barragan-Quintero, R.V. Does the Level of Academic Study Influence the Happiness of Spanish Entrepreneurs in Industry 4.0? In 2020 International Conference on Technology and Entrepreneurship—Virtual (ICTE-V); IEEE: San Jose, CA, USA, 2020; pp. 1–5.

- Renko, M.; El Tarabishy, A.; Carsrud, A.L.; Brännback, M. Entrepreneurial Leadership and the Family Business. In Understanding Family Businesses; Carsrud, A., Brännback, M., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 169–184.

- Kirkwood, J.; Tootell, B. Is Entrepreneurship the Answer to Achieving Work–Family Balance? J. Manag. Organ. 2008, 14, 285–302.

- Powell, G.N.; Eddleston, K.A. Linking Family-to-Business Enrichment and Support to Entrepreneurial Success: Do Female and Male Entrepreneurs Experience Different Outcomes? J. Bus. Ventur. 2013, 28, 261–280.

- Jennings, J.E.; McDougald, M.S. Work-Family Interface Experiences and Coping Strategies: Implications for Entrepreneurship Research and Practice. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 747–760.

- Douglas, E.J.; Shepherd, D.A. Entrepreneurship as a Utility Maximizing Response. J. Bus. Ventur. 2000, 15, 231–251.

- Hessels, J.; van Gelderen, M.; Thurik, R. Entrepreneurial Aspirations, Motivations, and Their Drivers. Small Bus. Econ. 2008, 31, 323–339.

- Olson, D.H.; Sprenkle, D.H.; Russell, C.S. Circumplex Model of Marital and Family Systems: I. Cohesion and Adaptability Dimensions, Family Types, and Clinical Applications. Fam. Process 1979, 18, 3–28.

- Beehr, T.A.; McGrath, J.E. Social Support, Occupational Stress and Anxiety. Anxiety Stress Coping 1992, 5, 7–19.

- Kaufmann, G.M.; Beehr, T.A. Interactions Between Job Stressors and Social Support: Some Counterintuitive Results. J. Appl. Psychol. 1986, 71, 522.

- Karatepe, O.M.; Yavas, U.; Babakus, E. The Effects of Customer Orientation and Job Resources on Frontline Employees’ Job Outcomes. Serv. Mark. Q. 2007, 29, 61–79.

- Cardon, M.S.; Kirk, C.P. Entrepreneurial Passion as Mediator of the Self–Efficacy to Persistence Relationship. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2015, 39, 1027–1050.

- Bignotti, A.; le Roux, I. Which Types of Experience Matter? The Role of Prior Start-up Experiences and Work Experience in Fostering Youth Entrepreneurial Intentions. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2020, 26, 1181–1198.

- Gorgievski, M.J.; Ascalon, M.E.; Stephan, U. Small Business Owners’ Success Criteria, a Values Approach to Personal Differences. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2011, 49, 207–232.

More