Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Jessie Wu and Version 1 by Ahcène Boumendjel.

Commercially available aminoacetophenones are used as "Swiss army knife" for the synthesis of a wide variety of natural products analogs with high therapeutic potential. Being short versatile and uses common reactions, the strategy can be explored in the generation of chemical libraries to be screened in the frame of drug discovery processes.

- Amino Acetophenones

1. Introduction

Due to an increasing and incessant need for small molecules used as drug candidates or molecular tools for therapeutic applications, organic and medicinal chemistry is considered the crux of both chemical genetics and drug discovery [1,2][1][2]. The main strategies to synthesize chemically diverse molecules can be classified into three approaches, namely, Target-Oriented Synthesis (TOS), Combinatorial Synthesis (CS), and Diversity-Oriented Synthesis (DOS). The TOS approach is focused on the synthesis of a single compound or a restricted class of compounds directed towards a biological target for a specific pharmaceutical area. TOS is the oldest approach whose advantage is the possibility to be planned through retrosynthetic analysis [3]. CS, on the other hand, has emerged as an indispensable strategy to significantly increase the diversity as well as the number of small molecules to be used for therapeutic and biological applications, contributing to the rapid discovery of potential hits [3]. Thanks to solid phase organic synthesis, which has its origins in peptide synthesis, CS takes full advantage of available automated systems. However, disadvantages may stem from the library design involved in this approach. Finally, DOS established itself as an attractive approach to produce large-sized chemical libraries [3[3][4],4], allowing access to a high number of compounds in a few steps starting from one building block that has to be affordable, safe, and either commercially available or easily prepared on a large scale [5,6,7,8,9][5][6][7][8][9]. On the basis of comparing the three aforementioned approaches, it can be deduced that TOS and CS focus on a few points in the chemical space, whereas DOS is meant to ensure large coverage of both the chemical space and molecular diversity, which is a significant advantage.

Besides the synthetic chemistry strategies discussed above, drug repositioning and natural products may lead to the discovery of potential hits. Drug repositioning, using large libraries of clinically used drugs to supplement high-throughput screening [10], is widely considered a promising approach as it speeds up the drug discovery process by bypassing some clinical trials that usually take up too much time and massive financial support. The natural products arena, on the other hand, is another major source of compounds from different origins, including plants, fungi, algae, insects, and animals [11[11][12],12], with countless known molecules and analogs used as major drugs targeting life-threatening diseases. In addition to relevant biological effects, natural products offer extraordinary and unpredictable chemical diversity that constitutes a source of inspiration for the medicinal chemistry community.

Based on the importance of both DOS and natural products in drug discovery, their combination could facilitate and accelerate the identification of novel compounds with improved biological activities [13,14][13][14]. This article, for this reason reviews the DOS of natural product analogs with a special focus on the synthesis of analogs of flavonoids and coumarins.

Flavonoids are chemical entities commonly found in fruits and vegetables. In addition to their contribution to plant growth and defense, they exhibit a wide range of biological effects against major diseases. The most known activity of flavonoids is their antioxidant effect, and, for this fact, they are often considered unique allies for the prevention of cardiovascular diseases, cancer, and neurological disorders [15,16,17][15][16][17]. Based on their structures, flavonoids are classified into many different sub-classes including flavones, isoflavones, flavonols, flavanones, chalcones, and aurones. In drug discovery, the tricyclic structure of naturally occurring flavonoids (2-Phenyl-4H-1-benzopyran-4-one) is used as a scaffold in pharmacophore-based drug design. The introduction of diverse functions on this chemotype has led to the identification of promising leads and drug candidates. One of the structural modifications operated during the optimization process is the introduction of amino groups onto the scaffold, either at the periphery of the flavonoidic structure (aminoflavones) or at the central ring through the replacement of the oxygen by an amino group (turning flavones to 2-phenyl-4-quinolones) [18,19][18][19]. In the same vein, the naturally occurring coumarins (1-benzopyran-2-one) were extensively investigated as scaffolds in drug discovery [20]. Similarly to what was said for flavonoids, one of the chemical modifications operated on coumarins is the substitution of the furanone ring’s oxygen atom with an amino group (turning coumarins into 2-quinolones). Classically, the introduction of amines on the flavonoid and the coumarin skeletons requires several synthetic steps and, in some cases, the use of toxic reagents [21]. This is especially the case when multifunctional derivatives of flavones and coumarins are targeted.

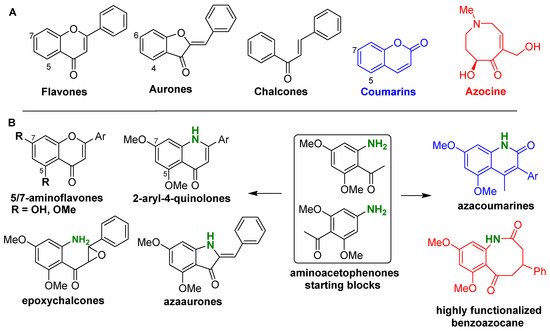

Based on our own work and literature survey, it was found that amino dimethoxyacetophenones can be used as a “Swiss army knife” that allows the access to a wide variety of bioactive compounds derived from flavones, aurones, chalcones, and coumarins in which an amino group was introduced (Figure 1). This includes aminoflavones, quinolones, azaaurones, aminoepoxychalcones, and azacoumarines. Moreover, by using the same agents, a highly functionalized azocine derivative, a benzoazocane recognized for its diverse biological activities, can be prepared through a novel and short synthetic scheme (Figure 1). It should be mentioned that the use of aminoacetophenone in drug discovery is ancient, as exemplified by chloramphenicol that is a widely produced antibiotic in recent decades [22].

Figure 1. Chemical structures reported in this review. (A) General structures of the targeted natural products; (B) Structures of the starting blocks and natural product analogs prepared.

2. Synthesis of the Starting Blocks

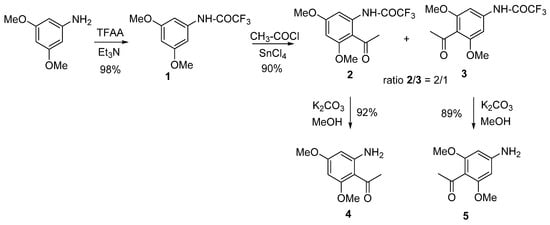

The aminodimethoxyacetophenones used as starting blocks were 2-amino-4,6-dimethoxyacetophenone (4) and 4-amino-2,6-dimethoxyacetophenone (5) (Scheme 1). The synthesis pathways of 4 and 5 are displayed in Scheme 1. The presence and the positions of the methoxy groups on the starting blocks were chosen in line with the common substitution patterns found in naturally occurring flavones, aurones, and coumarins, over 50% of which are hydroxylated and/or methoxylated at the 5, 7 positions (in flavonoids) and the 4, 6 positions (in aurones).

Scheme 1. Synthesis of the starting blocks.

The synthesis of the starting blocks was carried out from the commercially available 3,5-dimethoxy aniline, which was protected as a trifluoroacetamide (compound 1) then reacted with acetyl chloride in the presence of tin tetrachloride (SnCl4) to afford the two acetylated regioisomers 2 and 3 with a ratio of 2/1, respectively. The best Lewis acid needed for the acetylation step by far was SnCl4 (compared to AlCl3, SnCl2, ZnCl2), as it allowed the reaction to proceed in smooth conditions [23]. The trifluoroacetamide was deprotected in classical conditions by means of potassium carbonate in methanol to afford the corresponding aminoacetophenones 4 and 5 with excellent yields.

During the synthesis of 2 and 3, it was reported that, in the presence of a large excess of SnCl4, only the formation of 3 was observed, whereas 2 was only produced in traces. Later, it was found that the derivative 2 could undergo a deacetylation reaction when treated with an excess of SnCl4 [24] to give the starting compound (1). Interestingly, this deacetylation process was found to be regio- and chemo-selective, since no reaction occurred with the regioisomer 3 and the presence of N-acetyl or O-acetyl was not affected by this reaction. Finally, the presence of SnCl4 was required as no reaction was observed with alternative Lewis acids (AlCl3, SnCl2, ZnCl2) [23]. The access to derivatives 4 and 5 is easy and straightforward. The only drawback of the transformation is the use of tin(IV) salt that is reputed to be toxic.

3. Synthesis of 5- and 7-Aminoflavones

The naturally occurring flavones bearing the benzo-γ-pyrone structure are known for their versatile health benefits. Being polyhydroxylated, the hydroxyl groups in flavones mediate their antioxidant effects by scavenging free radicals and/or by metal chelation. Henceforth, it is now well established that the health-promoting properties of flavonoids originate from their high antioxidant capacity. In this context, flavonoids are recommended for their protective effects against chronic diseases including cancer, cardiovascular, and age-related disorders. During the Covid-19 world pandemic, flavonoids were among the most investigated and the most relevant natural products tested against the inflammatory storm caused by SARS-CoV-2 [25,26][25][26]. In the drug discovery domain, the scaffolds and the substitution patterns of naturally occurring flavones have been served as sources of inspiration for the design and development of flavones-derived drug candidates [27,28][27][28].

Among the structural modifications operated on flavonoids, the introduction of amino groups at the flavone scaffold was one of the most frequent [29,30,31,32][29][30][31][32]. For example, flavone derivatives bearing amino groups were studied as anticancer compounds [33,34,35,36][33][34][35][36]. Among them, flavopiridol was the first cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor to enter human clinical trials [36]. Another aminoflavone, known under the name Alvocidib (AFP 464, NSC710464), has been developed by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) investigational drug program and has entered clinical trials as a promising antitumor drug candidate for the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia [37,38,39,40][37][38][39][40]. This drug acts against estrogen-positive breast cancer (ER+) with a unique mechanism of action involving the activation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) signaling pathway [41].

As discussed above, whatever the origin of naturally occurring flavones, the most frequent structural feature in common is a hydroxy or a methoxy group at the 5 and 7 positions. Hence, amino groups are usually introduced into the flavone scaffold on the A-ring and especially at C5 and C7, where hydroxy groups were replaced by amino groups.

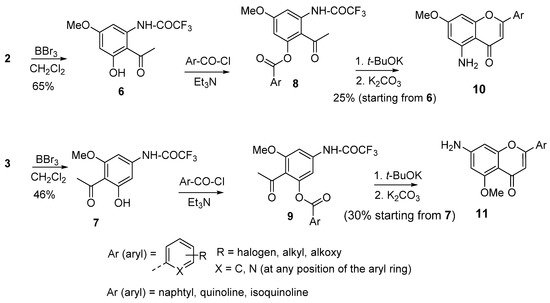

Classically, the synthesis of simple aminoflavones can be achieved by starting either from reagents already bearing either amino groups or nitro groups. In the latter case, a nitro 2-hydroxyacetophenone reacted with a benzoyl chloride to give the corresponding diketone intermediate that is cyclized in acidic conditions to provide the corresponding nitroflavone. Finally, the nitro group is reduced either by catalytic hydrogenation or by using metal salts to give the aminoflavone [42,43][42][43]. Unfortunately, in the latter case, the reduction conditions might be incompatible with the presence of sensitive functionalities. Hence, the prospect for any alternative method to access such compounds is of interest. In this regard, the amino dimethoxyacetophenones presented in Scheme 1 offer a simple way to obtain 5-aminoflavones and 7-aminoflavones (Scheme 2). To this end, the derivatives 2 and 3, shown in Scheme 1, were subjected to a selective demethylation reaction with diluted boron tribromide (BBr3) to provide the derivatives 6 and 7. Boron tribromide demethylation is favored at the position 5; higher concentrations and a longer reaction time are needed for a possible demethylation process at the position 7 [44]. The acetophenone derivatives 6 and 7 were esterified with aroyl chloride derivatives to provide the corresponding esters 8 and 9, which were not purified and directly cyclized upon treatment with a non-nucleophilic base such as potassium tert-butoxide. In cases where the desired aroyl chloride is not available, the corresponding aryl carboxylic acid can be used in the presence of a peptide coupling agent. Finally, the amino groups were deprotected by means of potassium carbonate to afford the aminoflavones 10 and 11 with acceptable mean yields, starting from 2 and 3. The method offers the advantage of being applicable to diverse derivatives bearing a large variety of substituents on the B-ring, including halogens, alkoxides, alkyls, heterocycles, and fused cycles. It should be noted that the methoxy groups of 10 and 11 can be deprotected to obtain the corresponding aminohydroxyflavones. The only limitation of the method is the moderate yield regarding the transformation of esters 8 and 9 to the final compounds.

Scheme 2. Synthesis of 5- and 7-aminoflavones.

References

- International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium. Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature 2001, 409, 860–921.

- Jones, L.H.; Bunnage, M.E. Applications of chemogenomic library screening in drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2017, 16, 285–296.

- Schreiber, S.L. Target-oriented and diversity-oriented organic synthesis in drug discovery. Science 2000, 287, 1964–1969.

- Galloway, W.R.J.D.; Isidro-Llobet, A.; Spring, D.R. Diversity-oriented synthesis as a tool for the discovery of novel biologically active small molecules. Nat. Commun. 2010, 1, 80.

- Kidd, S.L.; Osberger, T.J.; Mateu, N.; Sore, H.F.; Spring, D.R. Recent applications of diversity-oriented synthesis toward novel, 3-dimensional fragment collections. Front. Chem. 2018, 6, 460.

- Pavlinov, I.; Gerlach, E.M.; Aldrich, L.N. Next generation diversity-oriented synthesis: A paradigm shift from chemical diversity to biological diversity. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2019, 17, 1608–1623.

- Blakemore, D.C.; Castro, L.; Churcher, I.; Rees, D.C.; Thomas, A.W.; Wilson, D.M.; Wood, A. Organic synthesis provides opportunities to transform drug discovery. Nat. Chem. 2018, 10, 383–394.

- Meanwell, M.; Fehr, G.; Ren, W.; Adluri, B.; Rose, V.; Lehmann, J.; Silverman, S.M.; Rawshanpour, R.; Bergeron-Blerk, M.; Foy, H.; et al. Diversity-oriented synthesis of glycomimetics. Commun. Chem. 2021, 4, 96.

- Murlykina, M.V.; Morozova, A.D.; Zviagin, I.M.; Sakhno, Y.I.; Desenko, S.M.; Chebanov, V.A. Aminoazole-Based Diversity-Oriented Synthesis of Heterocycles. Front. Chem. 2018, 6, 527.

- Alderton, G. Drug repurposing. Science 2020, 368, 840–842.

- Atanasov, A.G.; Zotchev, S.B.; Dirsch, V.M.; Supuran, C.T. Natural products in drug discovery: Advances and opportunities. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2021, 20, 200–216.

- Shang, S.; Tan, D.S. Advancing chemistry and biology through diversity-oriented synthesis of natural product-like libraries. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2005, 9, 248–258.

- Prabhu, G.; Agarwal, S.; Sharma, V.; Madurkar, S.M.; Munshi, P.; Singh, S.; Sen, S. A natural product based DOS library of hybrid systems. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 95, 41–48.

- Chauhan, J.; Luthra, T.; Gundla, R.; Ferraro, A.; Holzgrabe, U.; Sen, S. A diversity oriented synthesis of natural product inspired molecular libraries. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2017, 5, 9108–9120.

- Khan, J.; Deb, P.K.; Priya, S.; Medina, K.D.; Devi, R.; Walode, S.G.; Rudrapal, M. Dietary Flavonoids: Cardioprotective Potential with Antioxidant Effects and Their Pharmacokinetic, Toxicological and Therapeutic Concerns. Molecules 2021, 26, 4021.

- Yammine, A.; Namsi, A.; Vervandier-Fasseur, D.; Mackrill, J.J.; Lizard, G.; Latruffe, N. Polyphenols of the Mediterranean Diet and Their Metabolites in the Prevention of Colorectal Cancer. Molecules 2021, 26, 3483.

- Pacifici, F.; Rovella, V.; Pastore, D.; Bellia, A.; Abete, P.; Donadel, G.; Santini, S.; Beck, H.; Ricordi, C.; Daniele, N.D.; et al. Polyphenols and Ischemic Stroke: Insight into One of the Best Strategies for Prevention and Treatment. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1967.

- Atwell, G.J.; Rewcastle, G.W.; Baguley, B.C.; Denny, W.A. Synthesis and antitumor activity of topologically-related analogs of flavoneacetic acid. Anti-Cancer Drug Des. 1989, 4, 161–169.

- Brana, M.F.; Castellano, J.M.; Emling, F.; Schlick, E. Synthesis and in vitro cytotoxic evaluation of new compounds with hybrid structures of 8-flavoneacetic acid and quinolones. An. Quim. 1994, 90, 491–496.

- Devulapally, S.; Chandraiah, G.; Pramod, K.D. A Review on Pharmacological Properties of Coumarins. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2018, 18, 113–141.

- Hadjeri, M.; Beney, C.; Boumendjel, A. Recent Advances in the Synthesis of Conveniently Substituted Flavones, Quinolones, Chalcones and Aurones: Potential Biologically Active Molecules. Curr. Org. Chem. 2003, 7, 679–689.

- Long, L.M.; Troutman, H.D. Chloramphenicol (Chloromycetin). IV. A synthetic approach. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1949, 71, 2469–2472.

- Traxler, P.; Green, J.; Mett, H.; Séquin, U.; Furet, P. Use of a pharmacophore model for the design of EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors: Isoflavones and 3-phenyl-4(1H)-quinolones. J. Med. Chem. 1999, 42, 1018–1026.

- Hadjeri, M.; Mariotte, A.-M.; Boumendjel, A. Deacetylation of activated acetophenones with tin(IV) chloride. J. Chem. Res. 2002, 2002, 463–464.

- Khazeei-Tabari, M.A.; Iranpanah, A.; Bahramsoltani, R.; Rahimi, R. Flavonoids as Promising Antiviral Agents against SARS-CoV-2 Infection: A Mechanistic Review. Molecules 2021, 26, 3900.

- Junaid, M.; Akter, Y.; Siddika, A.; Nayeem, S.M.A.; Nahrin, A.; Afrose, S.S.; Ezaj, M.M.A.; Alam, M.S. Nature-derived hit, lead, and drug-like small molecules: Current status and future aspects against key target proteins of Coronaviruses. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2021.

- Boniface, P.K.; Elizabeth, F.I. Flavones as a Privileged Scaffold in Drug Discovery: Current Developments. Curr. Org. Synth. 2019, 16, 968–1001.

- Ibrahim, N.; Bonnet, P.; Brion, J.D.; Peyrat, J.F.; Bignon, J.; Levaique, H.; Josselin, B.; Robert, T.; Colas, P.; Bach, S.; et al. Identification of a new series of flavopiridol-like structures as kinase inhibitors with high cytotoxic potency. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 199, 112355.

- Fabijańska, M.; Kasprzak, M.M.; Ochock, J. Ruthenium(II) and Platinum(II) Complexes with Biologically Active Aminoflavone Ligands Exhibit In Vitro Anticancer Activity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7568.

- Szappanos, Á.; Mándi, A.; Gulácsi, K.; Lisztes, E.; Tóth, B.I.; Bíró, T.; Kónya-Ábrahám, A.; Kiss-Szikszai, A.; Bényei, A.; Antus, S.; et al. Synthesis and HPLC-ECD Study of Cytostatic Condensed O,N-Heterocycles Obtained from 3-Aminoflavanones. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1462.

- Shelke, R.N.; Pansare, D.N.; Sarkate, A.P.; Narula, I.K.; Lokwani, D.K.; Tiwari, S.V.; Azad, R.; Thopate, S.R. Synthesis and evaluation of novel sulfonamide analogues of 6/7-aminoflavones as anticancer agents via topoisomerase II inhibition. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2020, 30, 127246.

- Brinkman, A.M.; Chen, G.; Wang, Y.; Hedman, C.J.; Sherer, N.M.; Havighurst, T.C.; Gong, S.; Xu, W. Aminoflavone-loaded EGFR-targeted unimolecular micelle nanoparticles exhibit anti-cancer effects in triple negative breast cancer. Biomaterials 2016, 101, 20–31.

- Thorat, N.M.; Sarkate, A.P.; Lokwani, D.K.; Tiwari, S.V.; Azad, R.; Thopate, S.R. N-Benzylation of 6-aminoflavone by reductive amination and efficient access to some novel anticancer agents via topoisomerase II inhibition. Mol. Divers. 2020, 25, 937–948.

- Fabijańska, M.; Orzechowska, M.; Rybarczyk-Pirek, A.J.; Dominikowska, J.; Bieńkowska, A.; Małecki, M.; Ochocki, J. Simple trans-platinum complex bearing 3-aminoflavone ligand could be a useful drug: Structure-activity relationship of platinum complex in comparison with cisplatin. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2116.

- Campbell, P.S.; Mavingire, N.; Khan, S.; Rowland, L.K.; Wooten, J.V.; Opoku-Agyeman, A.; Guevara, A.; Soto, U.; Cavalli, F.; Loaiza-Pérez, A.I.; et al. AhR ligand aminoflavone suppresses alpha6-integrin-Src-Akt signaling to attenuate tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 2018, 234, 108–121.

- Stompor, M.; Świtalska, M.; Bajek, A.; Wietrzyk, J. Influence of amide versus ester linkages on the anticancer properties of the new flavone–biotin conjugates. Z. Naturforsch. C 2019, 74, 193–200.

- Senderowicz, A.M. Flavopiridol: The first cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor in human clinical trials. Invest. New Drugs 1999, 17, 313–320.

- Kuffel, M.J.; Schroeder, J.C.; Pobst, L.J.; Naylor, S.; Reid, J.M.; Kaufmann, S.H.; Ames, M.M. Activation of the antitumor agent aminoflavone (NSC 686288) is mediated by induction of tumor cell cytochrome P450 1A1/1A2. Mol. Pharmacol. 2002, 62, 143–153.

- McLean, L.; Soto, U.; Agama, K.; Francis, J.; Jimenez, R.; Pommier, Y.; Sowers, L.; Brantley, E. Aminoflavone induces oxidative DNA damage and reactive oxidative species-mediated apoptosis in breast cancer cells. Int. J. Cancer 2008, 122, 1665–1674.

- Itkin, B.; Breen, A.; Turyanska, L.; Sandes, E.O.; Bradshaw, T.D.; Loaiza-Perez, A.I. New Treatments in Renal Cancer: The AhR Ligands. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3551.

- Callero, M.A.; Rodriguez, C.E.; Sólimo, A.; Offé, E.B.; Loaiza-Perez, A.I. The Immune System As a New Possible Cell Target for AFP 464 in a Spontaneous Mammary Cancer Mouse Model. J. Cell. Biochem. 2017, 118, 2841–2849.

- Tang, L.; Zhang, S.; Yang, J.; Gao, W.; Cui, J.; Zhuang, T. A Novel approach to the synthesis of 6-amino-7-hydroxy-flavone. Molecules 2004, 9, 842–848.

- Patoilo, D.T.; Silva, A.M.S.; Cavaleiro, J.A.S. Regioselective 3-nitration of flavones: A new synthesis of 3-nitro- and 3-aminoflavones. Synlett 2010, 9, 1381–1385.

- Deka, N.; Hadjeri, M.; Lawson, M.; Beney, C.; Mariotte, A.-M.; Boumendjel, A. Acetylated dimethoxyaniline as a key intermediate for the synthesis of aminoflavones and quinolones. Heterocycles 2002, 57, 123–128.

More