Ferdinand II king of Aragon (1479–1516). He was the fourth king of the Trastámara dynasty, which had first come to power after the Compromise of Caspe, reached after Martin I died with no living descendants in 1410. Although in terms of artistic patronage Ferdinand II was not as active as his wife Elisabeth I, he was still aware that the wise use of artistic commissions in reinforcing ideas and concepts favourable to the institution of the monarchy. He is a highly important figure in the history of Spain because, along with Elisabeth, he was one of the Catholic Monarchs and thus represents a new conception of power based on their joint governance, a fact that is reflected in the iconography found in his artistic commissions across all genres. All of the images are evidence of how King Ferdinand, at the end of the Middle Ages, wanted to be recognised by his subjects, who also used his image for legitimising and propagandistic purposes. Nobody else in the history of the Hispanic kingdoms had their image represented so many times and on such diverse occasions as did the Catholic Monarchs.

- royal images

- royal iconography

- kings of Aragon

- Crown of Aragon

- Fernando II of Aragon.

1. Introduction to the Reign of Ferdinand II

2. Character, Appearance and Artistic Patronage

3. Elements of a Legal Nature: Coins and Seals

3.1. Coins

3.2. Seals

4. Instrumental Character of Art

4.1. Government Images

4.2. The King as Caput Milicie

4.3. Devotional Images

5. A New Artistic Genre at Court: Portraiture

6. Conclusions

References

- Solano, F. Fernando el Católico y el Ocaso del Reino Aragonés; Universidad de Zaragoza: Zaragoza, Spain, 1979.

- Redondo, G.; Orera, L. Fernando II y el Reino de Aragón; Guara: Zaragoza, Spain, 1980.

- Sarasa, E. Aragón en el Reinado de Fernando I (1412–1416); Institución Fernando el Católico: Zaragoza, Spain, 1986.

- Sesma, J.A. Fernando de Aragón. Hispaniarum Rex; Gobierno de Aragón: Zaragoza, Spain, 1992.

- Belenguer, E. Ferran II. El rei del Redreç? Institut d’Estudis Catalans: Barcelona, Spain, 2017.

- Salicrú, R. De Martí I l’Humà, del Compromís de Casp o de Ferran I a Ferran II: La Catalunya del segle XV, un segle de canvis i transicions. In El segle XV, Temps de Canvis i Incerteses; Arxiu de Vilassar de Dalt: Vilassar de Dalt, Spain, 2017; pp. 17–36.

- Pulgar, H. Crónica de Los Reyes Católicos; Biblioteca de Autores Españoles: Madrid, Spain, 1953; tom. LXX, cap. III, 2nd part; p. 255.

- Yarza, J. Los Reyes Católicos. Paisaje Artístico de una Monarquía; Nerea: Madrid, Spain, 1993; pp. 114–121.

- Dietaris de la Generalitat de Catalunya, 1411–1714; Sans, J.M. (Dir.) (Ed.) Generalitat de Catalunya: Barcelona, Spain, 2000.

- Duran, A. Barcelona i la Seva Història; Curial: Barcelona, Spain, 1975; Volume II, p. 133.

- Serrano, M. Ferdinandus Rei Gracia Rex Aragonum. La efigie de Fernando II el Católico en la Iconografía Medieval; Institución Fernando el Católico: Zaragoza, Spain, 2014; pp. 51–54.

- Andrew, E. The foxy prophet: Machiavelli versus Machiavelli on Ferdinand the Catholic. Hist. Political Thought 1990, 11, 409–422.

- Yarza, J. Gusto y promotor en la época de los Reyes Católicos. Ephialte 1992, III, 21–70.

- Yarza, J. Imágenes reales hispanas en el fin de la Edad Media. In Poderes Públicos en la Europa Medieval: Principados, Reinos y Coronas; Gobierno de Navarra: Pamplona, Spain, 1997; pp. 441–500.

- Yarza, J. Entre Flandes e Italia. Dos modelos y su adopción en la España de los Reyes Católicos. In Los Reyes Católicos y la Monarquía de España; Generalitat de València: Valencia, Spain, 2001; pp. 313–327.

- Yarza, J. Política artística de Fernando el Católico. In De la Unión de Coronas al Imperio de Carlos V; Belenguer, E., Ed.; Sociedad Estatal para la conmemoración de los centenarios de Felipe II y Carlos V: Madrid, Spain, 2001; pp. 15–29.

- Yarza, J. La Nobleza Ante el Rey. Los Grandes Linajes Castellanos y el Arte del Siglo XV; Viso: Madrid, Spain, 2003.

- Crusafont, M. Numismática de la Corona Catalano-Aragonesa Medieval (785–1516); Vico: Madrid, Spain, 1982; p. 137.

- Campo, M. (coom.). La Imatge del Poder a la Moneda; Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya: Barcelona, Spain, 1998; p. 23.

- Álvarez-Ossorio, F. Catálogo de las Medallas de los Siglos XV y XVI; Cuerpo Facultativo de Archiveros, Bibliotecarios y Arqueólogos: Madrid, Spain, 1950; pp. 377–384.

- Crusafont, M. Acuñaciones de la Corona Catalano-Aragonesa y de los Reinos de Aragón y Navarra. Medioevo y Tránsito a la Edad Moderna; Vico: Barcelona, Spain, 1992; pp. 68–69.

- Mateu, F. La Iconografía Sigilográfica y Monetaria de los Reyes Católicos; Anales y Boletín de los Museos de Arte: Barcelona, Spain, 1944; p. 16.

- Murray, G. La moneda durante el reinado de Isabel la Católica. In Isabel, Reina de Castilla; Caja de Segovia: Segovia, Spain, 2004; pp. 243–264.

- Alfaro, C. La reforma de la moneda. In Los Reyes Católicos y la Monarquía de España; Generalitat de València: Valencia, Spain, 2001; pp. 97–104.

- Balaguer, A.M.; García, M.; Crusafont, M. Historia de la Moneda Catalana; Caja de Barcelona: Barcelona, Spain, 1986; p. 73.

- Sanz, C. Las primeras acuñaciones de los Reyes Católicos. Rev. Arch. Bibl. Mus. 1920, XLI, 71.

- Balaguer, A.M. La moneda y su historia en el reinado de los Reyes Católicos. Numisma 1993, 233, 138.

- Gallego, P. Dineral inédito. Numisma 1996, 238, 238.

- De Sagarra, F. Sigil·Lografia Catalana. Inventari, Descripció i Estudi Dels Segells de Catalunya; Estampa d’Henrich: Barcelona, Spain, 1916–1932; p. 109.

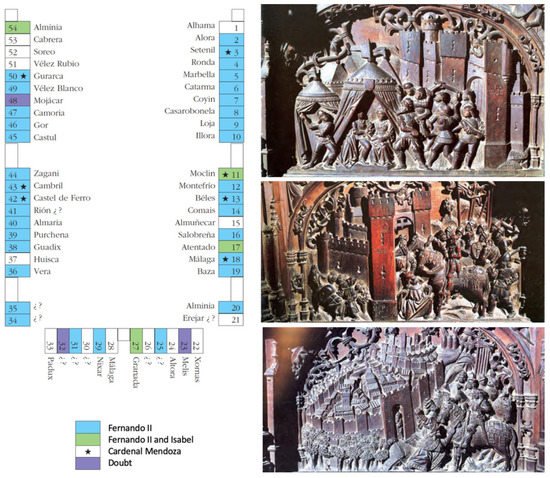

- Carriazo, J. Los Relieves de la Guerra de Granada en la Sillería del Coro de la Catedral de Toledo; Universidad de Granada: Granada, Spain, 1985.

- Checa, F. Poder y piedad: Patronos y mecenas en la introducción del Renacimiento en España. In Reyes y Mecenas. Los Reyes Católicos-Maximiliano I y los Inicios de la Casa de Austria en España; Ministerio de Cultura: Toledo, Spain, 1992; p. 30.

- Pereda, F. Los relieves toledanos de la guerra de Granada: Reflexiones sobre el procedimiento narrativo y sus fuentes clásicas. In Correspondencia e Integración de las Artes; Coloma, I., Sánchez, J.A., Eds.; Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte: Málaga, Spain, 2003; p. 345.

- Arena, H. Las sillerías de coro del maestro Rodrigo Alemán. Bol. Semin. Arte Arqueol. 1966, XXXII 1, 95.

- Mogollón, P.; Pizarro, F.J. La sillería de coro de la Catedral de Plasencia; Universidad de Extremadura: Salamanca-Soria, Spain, 1992; p. 11.

- Teijeira, M.D. Estalos de los Reyes Católicos. In Maravillas de la España Medieval. Tesoro Sagrado y Monarquía; Bango, I., Ed.; Caja España: León, Spain, 2000; p. 366.

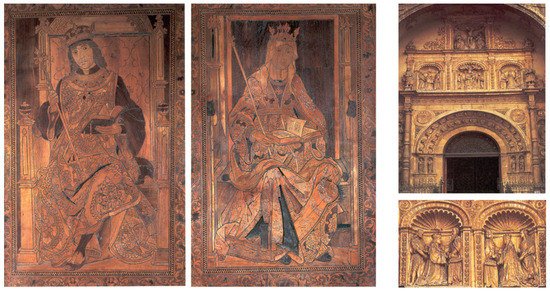

- Checa, F. Fernando el Católico. Isabel la Católica. In Reyes y Mecenas. Los Reyes Católicos-Maximiliano I y los Inicios de la Casa de Austria en España; Ministerio de Cultura: Toledo, Spain, 1992; p. 426.

- Galiay, J. Retrato de los Reyes Católicos en la portada de la Iglesia de Santa Engracia de Zaragoza. Semin. Arte Aragones 1945, 1, 7–14.

- Morte, C. Fernando el Católico y las artes. In Las Artes en Aragón Durante el Reinado de Fernando el Católico 1479–1516; Institución Fernando el Católico: Zaragoza, Spain, 1993; p. 162.

- Ibáñez, J. La portada de Santa Engracia. In Santa Engracia. Nuevas Aportaciones para la Historia del Monasterio y Basílica; Gobierno de Aragón: Zaragoza, Spain, 2002; pp. 179–207.

- Sigüenza, J. Historia de la Orden de San Jerónimo; Bailly-Bailliere: Madrid, Spain, 1909; Volume II, p. 52.

- Morte, C. Patrocinio artístico de los reyes y de la nobleza en Aragón a finales del Gótico y durante el Renacimiento. In Actes del I, II i III Col·loquis sobre Art i Cultura a l’època del Renaixement a la Corona d’Aragó; Ajuntament de Tortosa: Tortosa, Spain, 2000; p. 150, n. 7.

- Morte, C. La iconografía real. In Fernando II de Aragón. el Rey Católico; Institución Fernando el Católico: Zaragoza, Spain, 1996; p. 54.

- Esteban, J.F. Museo colegial de Daroca; Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia: Madrid, Spain, 1975; pp. 36–37.

- Lacarra, C. Conjunto de tablas con el milagro de los Sagrados Corporales. In El espejo de Nuestra historia. La diócesis de Zaragoza a Través de los Siglos; Arzobispado y Ayuntamiento de Zaragoza: Zaragoza, Spain, 1991; p. 450.

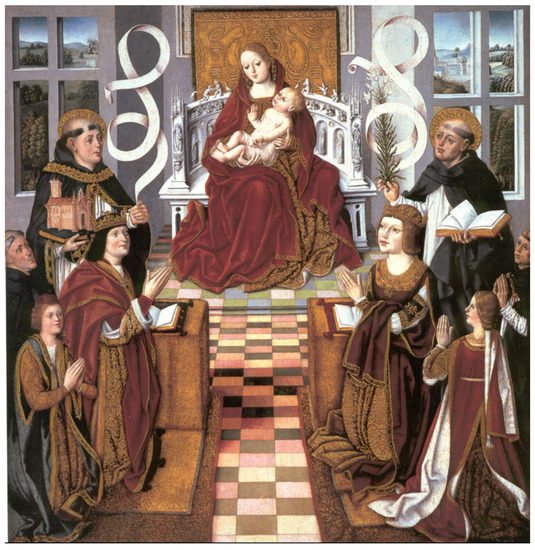

- Sorroche, M.A. Anónimo, Escuela hispanoflamenca. Piedad con los santos Juanes y los Reyes Católicos. In Los Reyes Católicos y la Monarquía de España; Generalitat de València: Valencia, Spain, 2001; p. 359.

- Silva, M.P. Pintura hispanoflamenca: Burgos y Palencia. Obras en Tabla y Sarga; Junta de Castilla y León: Valladolid, Spain, 1990; Volume II, p. 400.

- Yarza, J. Un arte al servicio de los reyes. In Isabel I, Reina de Castilla; Caja de Segovia, Obra Social y Cultural: Segovia, Spain, 2004; p. 147.

- Carderera, V. Iconografía Española. Colección de Retratos, Estatuas, Mausoleos y Demás Monumentos Inéditos de Reyes, Reinas, grandes Capitanes, Escritores, etc. Desde el Siglo XI Hasta el XVII; Ramón Campuzano: Madrid, Spain, 1855–1864; planche LVII.

- Yarza, J. El retrato medieval: La presencia del donante. In El Retrato en el Museo del Prado; Anaya: Madrid, Spain, 1994; pp. 90–92.

- Angulo, D. Isabel la Católica, sus Retratos, sus Vestidos, sus Joyas; Universidad Menéndez Pelayo: Santander, Spain, 1951; p. 46.

- Frieländer, M.J. Neus über den Meister Michiel und Juan de Flandes. Cicerone 1929, 21, 249.

- Sesma, A. Tablas procedentes del políptico de Isabel la Católica 1496–1504. In Reyes y Mecenas. Los Reyes Católicos-Maximiliano I y los Inicios de la Casa de Austria en España; Ministerio de Cultura: Toledo, Spain, 1992; pp. 465–468.

- Cela, M.E. Elementos Simbólicos en el arte Castellano de los Reyes Católicos; Universidad Complutense: Madrid, Spain, 1991; pp. 482–520.

- Gudiol, J. La Pintura Mig-Eval Catalana; Babra: Barcelona, Spain, 1927; Volume II, p. 19.

- Angulo, D. Un nuevo retrato de Isabel la Católica. Archivo Hispalense. Revista Histórica, Literaria y Artística 1951, 14, 333–335.

- Schütz, K. Retrato del rey Fernando el Católico de Aragón. In Reyes y Mecenas. Los Reyes Católicos-Maximiliano I y los Inicios de la Casa de Austria en España; Ministerio de Cultura: Toledo, Spain, 1992; p. 419.

- Fernández, I. Anónimo. Fernando el Católico. In Los Reyes Católicos y la Monarquía de España; Generalitat de València: Valencia, Spain, 2001; p. 372.