Due to the depletion of fossil fuels, biofuel production from renewable sources has gained

interest. Malaysia, as a tropical country with huge resources, has a high potential to produce different

types of biofuels from renewable sources. In Malaysia, biofuels can be produced from various sources,

such as lignocellulosic biomass, palm oil residues, and municipal wastes. Besides, biofuels are divided

into two main categories, called liquid (bioethanol and biodiesel) and gaseous (biohydrogen and

biogas). Malaysia agreed to reduce its greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 45% by 2030 as they

signed the Paris agreement in 2016. Therefore, we reviewed the status and potential of Malaysia as

one of the main biofuel producers in the world in recent years. The role of government and existing

policies have been discussed to analyze the outlook of the biofuel industries in Malaysia.

- biofuel production

- biogas

- bioethanol

- biohydrogen

- biodiesel

- Malaysia

1. Introduction

- Introduction

Recently, concerns about the depletion of conventional fuels (oil, natural gas, and coal), global warming, and the related environmental issues have drawn the government’s, researchers’, and policy-makers’ attention to identifying new energy sources [1]. Consequently, biofuels could be considered as an alternative to reduce high dependence on diesel fuels [2]. Besides this, the over-utilization of conventional fuels and their side effects on the Earth has increased the demand for liquid fuels produced from biomass throughout the world. According to estimations, the bioenergy production would be increased 4.7 times (from 9.7 × 106 to 4.6 × 107 GJ/d) between 2016 and 2040. However, it is noteworthy to mention that the biofuel production process influences their environmental impact [3].

Conventional fuels accounted for 80% of the primary energy consumption throughout the world in 2019, out of which about 60% were consumed by the transport sector [4]. Biofuels are classified into four types, called bioethanol, biodiesel, biogas, and biohydrogen. Each type of these fuels can be produced from different sources, such as edible and non-edible or food-based and waste-based [3]. Consequently, the demand for biodiesel, biogas, and bioethanol has increased. Therefore, achieving balance in the market and meeting the growing demand needs more production [5].

Generally, biofuels are divided into four main categories based on their production sources. The first generation is food-based biofuels and has several advantages, such as low production cost and effective production methods, which result in lower CHG emissions. Hence, the main issue of this type of biofuel is competition with food, which is a critical problem for consideration [6].

The main feedstock for second-generation biofuels is biomass, which is classified into two groups: (1) agricultural residues, such as sweet sorghum, sugarcane bagasse, and straws; (2) forest residues, such as energy crops and woody plants [7][8][7,8].

Third-generation biofuels are called algae-based biofuels, with the advantage of higher productivities per unit of area than other biofuel types of crops [9]. Meanwhile, fourth-generation biofuel is named genetically modified algae, with advantages such as having no food-energy conflict, requiring no arable land, and having an easy conversion. It is in the early stages of development, as reported by Abdullah et al. [10].

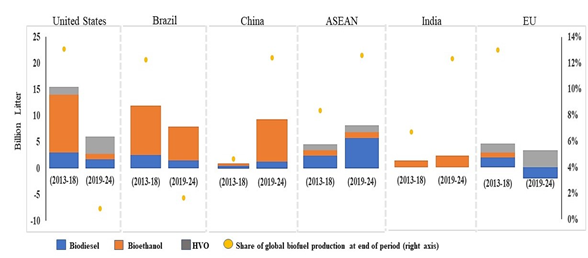

Figure 1 shows the increasing worldwide trend of biofuel production, which will reach 25% by 2024 [11]. Asia accounts for half of the growth, in which China is the largest biofuel producer to ensure its energy security and improve air quality [12]. Brazil is the second largest producer; meanwhile. two-thirds of the total biofuel production will be provided by the United States and Brazil in 2024 [13].

Figure 1. Biofuel production growth worldwide. Hydrotreated Vegetable Oil (HVO). The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN).

2. Possible Biomass Sources for Biofuels Production in Malaysia

- Possible Biomass Sources for Biofuels Production in Malaysia

Tropical regions such as Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) have large areas of natural arable land for biomass production, which could be used to produce biofuel. The ASEAN countries have promoted their national programs to increase their biofuel industry equipped with modern and advanced technologies [14], and [15]. The rate of energy demand has increased in Malaysia due to industrialization and the increasing population (32.4 million, with an annual growth rate of 1.4% in 2018), which could be a problem in the next 40 years because of fossil fuel resource depletion [16]. Moreover, still the transport sector consumed more than 70% of the total energy in Malaysia, which is petroleum-based diesel and gasoline fuels [17]. Besides this, Malaysia is a developing country that has planned and developed its biomass industry and is targeted to become a developed country by 2030 [18].

In the last three decades, Malaysia has become one of the most important poles of biofuel technology in the world due to its abundant natural sources (forests and agricultural fields cover 76% of its total land). In this regard, several strategies have been implemented by the Malaysian government [19].

On the other hand, there are many sources such as biomass waste in Malaysia which can be used as a suitable replacement for fossil fuels [20][21][22][23][24][20–24]. This country produces 168 million tons of biomass annually, including rice husks, timber, coconut trunk fibers, oil palm waste, and municipal wastes.

For instance, Malaysia, with more than 20 million tonnes of palm oil production, placed as the world’s second-largest producer in 2019 [25], and is forecasted to produce 20.3 million tonnes in 2020 [26]. It noteworthy to mention that Palm Oil Mill Effluent (POME) is wastewater produced from the oil palm industry and has environmental side effects if discharged into the environment. It contains a high level of organic nutrients, which can be converted to useful products such as biofuel [27]. Moreover, owning 58% of the world’s palm oil production, Indonesia and Malaysia are considered the two largest producers [14]. In 2016, extracting 17.32 million tonnes of crude palm oil from the palm oil mills, oil palm plantations in Malaysia have surged to 5.74 million hectares [28].

POME is a potential source of biofuel production in Malaysia by approximately 58 million tons annually. Besides this, other agricultural products such as rubber, paddy, and different palm oil products have the potential to be used as sources of biofuel production. The oil palm residues are oil palm trunks, empty fruit bunches (EFBs), crude palm oil, oil palm trunk (OPT), Palm Kernel Shell (PKS), and mesocarp fiber [2]. Palm oil mill biomass mainly consists of cellulose (24–65%), hemicellulose (21–34%), and lignin (14–31%) [29]. The high cellulose content of oil palm biomass oil makes it a suitable source to produce different types of biofuels. Table 1 shows the oil palm plantation area based on the states in Malaysia.

Table 1. The cultivation field for oil palm in Malaysia.

|

State |

Cultivation Area (Million Hectares/Year) |

||

|

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

|

|

Peninsular Malaysia |

2.3 |

2.4 |

2.4 |

|

Sabah and Sarawak |

2.7 |

2.7 |

2.8 |

|

Total |

5.0 |

5.1 |

5.2 |

Source: adopted from [30].

3. Biofuel Production in Malaysia

- Biofuel Production in Malaysia

In the following sections, the potential of each biofuel type (bioethanol, biodiesel, biohydrogen, and biogas) in Malaysia is summarized and discussed. Then, the impact of these fuels on the Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions is investigated, and so are the government strategies and policies based on current development programs that have been undertaken.

3.1. Bioethanol Production

One of the most beneficial biofuels is bioethanol, which can be substituted for fossil fuels [31][32][31,32]. Due to their low-cost production and lower GHG emissions, sugar-based feedstocks are a valuable candidate to be used for bioethanol production with a high yield [33][34][33,34]. Due to the existence of the rich tropical biodiversity in Malaysia and also the higher consumption of bioethanol by vehicles rather than biodiesel, the bioethanol market of Malaysia has gained attention from researchers [35][36][35,36].

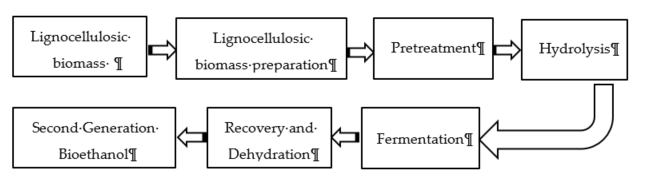

In Malaysia, the technology for ethanol production has not been fully commercialized due to several barriers, such as (1) the high transportation cost from rural plantations to urban processing plants, (2) the high capital investment, and (3) the lack of advanced technology [37]. However, after the promulgation of biofuel policies in 2006 and the increase in palm oil production, a significant growth in bioethanol production was observed [38][2,38]. Biomass such as lignocellulosic material is used as a renewable energy source [39][40][39,40]. Lignocellulosic biomass contains lignin, cellulose, and hemicellulose in a complex structure. It requires taking a pretreatment step to break down the bonds inside the polymers to smaller subunits [39]. The bioethanol production process includes 1—pretreatment; 2—hydrolysis; 3—fermentation; 4—distillation and ethanol recovery. In the pretreatment step, the lignocellulosic compounds deform the cellulose, lignin, and hemicellulose structure and degrade the crystallinity degree to make it ready for the hydrolysis step [41][42][41,42]. During hydrolysis, enzymes are used to cleave the carbohydrate chains, which has a direct effect on the quality of ethanol production [43][44][43,44]. Other influencing parameters for second-generation bioethanol production are the capital cost of the plant and the cost of feedstock, enzyme, and energy [45].

In the next step, microorganisms use the available sugars in pretreated biomass in the fermentation step. This process can be considered as Separate Hydrolysis and Fermentation (SHF) and Simultaneous Saccharification and Fermentation (SSF). In the SHF process, the separation of the fermentation and hydrolysis process occurs in two different stages, while SSF happena simultaneously [46]. Figure 2 illustrates the bioethanol production pathway from lignocellulosic materials.

Figure 2. Pathway of ethanol production from lignocellulosic biomass.

The influential factors on bioethanol production can be listed as temperature, pH, and fermentation time. The ideal temperature and optimal pH range in the fermentation process to produce ethanol should be between 20 and 35 and 4 and 5, respectively [47]. In 2015, Aditiya et al. [48] used mechanical and acid pretreatment for rice straw biomass at 90 for 60 min, which had total glucose of 11.466 g/L. Additionally, the combination of acid pretreatment with enzymatic hydrolysis yielded a higher ethanol content (52.75%) than the acidic pretreatment (11.26%). In another study, Jung et al. [49] used oil palm empty bunches under dilute sulfuric acid pretreatment and microwaving at 190 which led to a total glucose yield of 88.5% and an ethanol yield of 52.5%. Table 2 presents the recent studies of bioethanol production from different sources in Malaysia.

Table 2. Recent studies on bioethanol production from different sources in Malaysia.

Feedstock | Pretreatment Type | Experiment Condition | Fermentation Condition | (Temperature, pH, Duration) | Ethanol Yield | Reference |

Sugarcane bagasse | NaOH | Anaerobic condition without agitation | 50 °C for 2 days | 4.5 g/100 g |

[50] |

||||||||||||||

Formosana wood chips | Acid steam explosion, bleached acid steam explosion | 25 °C–160 °C, heating rate of 1.5 °C for 180 min | 37 °C for 120 h | 4.18 & 3.62 g/g |

[51] |

||||||||||||||

Frond part of banana plant | Ammonia | 0.1 M NaOH 0.1 M H2SO4 | 30 °C, pH 6.8 | 57 h | 45.75 g/L |

[40] |

|||||||||||||

Food waste | Hydrothermal and dilute acid pretreatment | Aseptic conditions | 30 °C, pH at 6.5–7.0 for 120 h | 0.42 g/g |

[52] |

||||||||||||||

Rice straw | Diluted acid | 50 °C, pH 5.0 | 72 h | 30 °C, pH 6.0 | 0.51 g/g |

[53] |

|||||||||||||

Oil-palm | Alkali | 3% NaOH solid-liquid charge (1:8) 110 °C, 45 min | 30 °C, 14–16 h | 0.33 g/g |

[54] |

||||||||||||||

Oil palm frond | Hydrothermal | 121 °C for 30 min | 30 °C, 24 h | 0.48 g/g |

[43] |

||||||||||||||

Oil palm empty fruit bunch | Bisulfite | 180 °C for 30 min | 30 °C, 24 h | 48 g/L |

[55] |

||||||||||||||

Sago pith waste | Microwave-assisted acid | Drying: 2 h | Milling: 1 min | Hydrolysis:1 min | 30 °C, 36 h | 0.31 g/g |

[44] |

||||||||||||

Palm empty fruit bunch | Organosolv | 60 min at 120 °C | 100 °C for 45 min | 133.17 mg/L |

[56] |

||||||||||||||

Water Hyacinth | Acid | 70 °C for 24 h | 30 °C, 72 h | 0.42 g/g |

[57] |

3.2. Biodiesel Production

As a liquid biofuel and non-pollutant fuel, biodiesel could be regarded as an alternative to conventional fuels because of its advantages over fossil fuels [2]. One of the most significant benefits of biodiesel is its renewability property, which allows it to have lower toxicity levels and pollutant emissions. Being degradable biologically, and its applicability to be used as an engine fuel are other advantages of this fuel [58][59][58,59].

Due to the high production of palm oil in the world, Malaysia has been considered as one of the top palm-based biodiesel producers [60][61][60,61]. Producing biodiesel in this country dates back to late 2005 due to the lower price of crude palm oil compared to that of crude oil [61]. Malaysia has a promising trend only for biodiesel by 490 million liters in 2017, which is expected to reach 815 million liters in 2027, showing a 66% increase [62][63][62,63].

Indeed, based on the type and availability of the feedstock, biodiesel could be classified into two main groups, called edible and non-edible (vegetable oil, algal oil, waste animal oil, waste cooking oil) [64]. Different feedstocks could be used to produce biodiesel [63]. The first, second, and third generation of biodiesel are produced from edible oil, non-edible oil feedstocks, and algae oil, respectively. Compared to edible and non-edible feedstocks, algae has a high oil content (30–70%), which made it suitable for biodiesel production [63][65][63,65].

Besides this, selecting the feedstock to produce biodiesel mainly depends on the economic aspect of the country and the availability of the feedstock, which should be considered before deciding to select it. In Malaysia, the most common sources for biodiesel production are palm oil and coconut oil, while India uses non-edible vegetable oils, such as Jatropha, Simarouba, and Karanja [66][67][57,66,67].

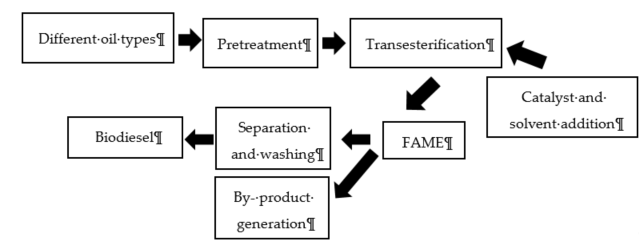

The composition and purity of the obtained biodiesel are determined based on the used feedstock [63]. Besides this, the molar ratio (alcohol to oil), reaction temperature, time, concentration, and type of catalyst are the most influential factors in the production process [58]. There are two different approaches for biodiesel production: either single- (transesterification) or two- (ester-transesterification) step processes [68]. Due to its lower production cost, higher yield, and a more sustainable pathway, transesterification is the most common method for biodiesel production [58]. Producing biodiesel via transesterification includes the catalytic hydro processing of triglycerides and the thermal conversion of lignocellulose, employing gasification and pyrolysis [69]. The esters and glycerol are produced in transesterification from the reaction of triglyceride (free fatty acid) and alcohol. Based on the weight of biodiesel and glycerol, they settle on the top and bottom, after separating the end products of the transesterification [70]. The schematic process is shown in Figure 3 [58].

Figure 3. Biodiesel production via the transesterification process.

The recent studies on biodiesel production from different sources in Malaysia are reported in Table 3.

Table 3. Recent studies on biodiesel production from different sources in Malaysia.

|

Feedstock |

Catalyst Type |

Experiment Condition |

|

Biodiesel Yield (%) |

Reference |

||

|

Catalyst Loading (wt%) |

Molar Ratio |

Reaction Time (min) |

Reaction Temperature (°C) |

||||

|

Palm oil based WCO |

LBC |

5.47 |

12.21:1 |

55.26 |

|

up to 96.65 |

[71] |

|

WCO |

Na2O impregnated-CNTs nanocatalyst |

5 |

20:1 |

240 |

90 |

97 |

[72] |

|

WCO |

BaSnO3 |

6 |

10:1 |

120 |

90 |

96 |

[73] |

|

WCO |

calcined fusion waste chicken and fish bones |

1.98 |

10:1 |

114 |

65 |

89.5 |

[74] |

|

OPEFB |

(4-BDS) |

20 |

|

420 |

110 |

98.1 |

[75] |

|

A. korthalsii seeds |

Marine barnacle |

4.7% |

12.2:1 |

180 |

65 |

97.12 ± 0.49 |

[76] |

|

OPEFB |

carbon-based solid acid |

10% |

50:1 |

480 |

100 |

FAME yield of 50.5% |

[77] |

|

Palm oil |

La-dolomite catalyst |

7 |

|

180 |

65 |

98.7 |

[78] |

LBC: activated limestone-based catalyst. 4-BDS: 4-benzenediazonium sulfonate. WCO: Waste Cooking Oil. Oil palm empty fruit bunch (OPEFB). Lanthanum complex dolomite (La-dolomite catalyst).

3.3. Biohydrogen Production

Hydrogen is an alternative renewable energy source that produces (122 kJ/g) energy and zero-carbon emission [79]. It can be replaced by non-renewable energy sources that will contribute about 8–10% of the world’s total energy by 2025, as estimated by the US Department of Energy [80][81][80,81]. Hence, several studies have been conducted on biohydrogen production from lignocellulose biomass such as oil palm biomass. In a developing country such as Malaysia, biohydrogen could serve as a remarkable clean energy source. Therefore, hydrogen is getting more attention as a promising replacement for existing fossil fuels. Based on the estimation, Malaysia will have the highest mean real output growth rate of the biohydrogen sector from 2017 to 2040 of 5.02%, in comparison with countries such as Japan, China, India, and Korea [82].

The bio-conversion of lignocellulose biomass into hydrogen requires several pretreatment methods that include physical and chemical approaches for the delignification of the biomass [83]. For example, during the thermochemical process, temperature and pressure are maintained to change the structure of biomass chemically to be able to produce a high yield of hydrogen. Gasification and pyrolysis are amongst well-known thermochemical methods to produce hydrogen [84]. Hence, the biological processes encompass the presence of microorganisms during the fermentation process to break down the polysaccharides towards producing hydrogen [85][86][85,86].

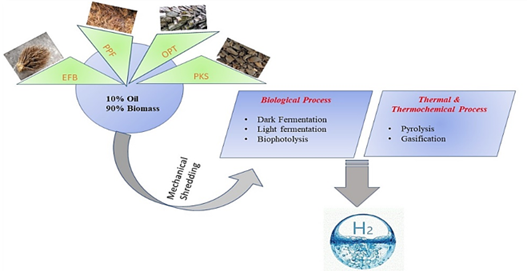

The fermentative bacterium can convert complex organic wastes into hydrogen energy during the fermentation process. Therefore, the maximum yield of H2 production has proportional influenced by the bacterial inoculum, substrate, and other physical parameters [87][88][87,88]. Facultative and obligate anaerobes are promising microorganisms for hydrogen production via fermentation. Particularly, facultatively anaerobic bacteria such as Enterobacter aerogenes and Bacillus sp effectively produce hydrogen in fermentation processes. Figure 4 illustrates the pathway conversion of palm oil mill waste to biofuel production, with an emphasis on producing hydrogen [89].

Figure 4. Biohydrogen production from palm oil mill biomass. PPF: palm pressed fiber.

Oil palm mill wastes consist of cellulose and hemicellulose. They are rich in pentose and hexose, which makes them favorable substrates to produce biohydrogen. For instance, POME contains high concentrations of free fatty acids, which is a suitable substrate to be used in the fermentation process for hydrogen production [90]. Several studies reported the biohydrogen production from POME. As reported by Abdullah et al. [91], a 22% increase in hydrogen production with a yield of 1.88 mol H₂/mol sugar obtained as POME was used as the feedstock. In addition, adjusting the C/N ratio can help to boost hydrogen production. It should be noted that excessive nitrogen could inhibit hydrogen production, while lower concentrations also cause nutrient deficiency and low-yield hydrogen production. Additionally, the C/N ratio directly affects the growth of microbes during the fermentation process for effective biohydrogen production [92].

Mishra et al. [93] isolated a novel mesophilic bacterial strain from palm oil mill sludge obtained from the FELDA palm oil industry in Pahang, Malaysia. The strain can produce the highest hydrogen yield of 2.42 mol H2/mol glucose. From results, indigenous isolated strains from palm oil biomass showed more positive impacts on hydrogen production compared to the exogenous sources. It is worth noticing that using a genetically modified organism like Escherichia coli (E. coli) is another useful pathway for increasing the substrate fermentation rate in hydrogen production [94]. Table 4 shows recent studies of biohydrogen production from POME in Malaysia.

Table 4. Recent studies of hydrogen production from different sources of oil palm biomass.

|

Feedstock |

Pretreatment Type |

Experiment Condition (Inoculum) |

Fermentation (Temperature, pH) |

Biohydrogen Yield |

Reference |

|

POME |

No pretreatment |

POME heat treated sludge (80 °C for 60 min) |

55 °C/6.0 |

1.88 molH₂/mol sugar |

[91] |

|

POME |

Ultrasonicated POME |

POME heat treated sludge (heated at 70 °C for 10 min; 90 °C and 110 °C for 10 min) |

37 °C/5.5 |

14.62 mL H2 h−1 g−1 |

[85] |

|

POME |

Pre-settled by keeping 24 h in cold treatment 4 °C |

POME heated treated anaerobic sludge at 80 °C for 50 min |

38 °C/5.5 |

3.2 mol H2/mol Sugar |

[95] |

|

POME |

Pre-dark fermentation by Bacillus anthracis |

Rhodo pseudomanas palustris in photo anaerobic sludge |

30 °C/7.0 |

3.07 ± 0.66 H2/mol-acetate |

[96] |

|

POME |

Pre-settled by keeping 24 h in cold treatment 4 °C |

POME digested sludge (heated 100 °C for 60 min) |

38 °C/5.5 |

0.31 L H2 g−1 COD |

[97] |

|

POME |

No pretreatment |

Anaerobic sludge was heat treated at 75 °C, 85 °C and 110 °C for 10 min |

37 °C/N.A |

352 mL H2 h−1g−1 |

[93] |

|

POME |

pH 8.5 with autoclave at 121 °C for 20 min |

Engineered E. coli strain in LB medium, growth at 37 °C |

37 °C/N. A |

3551 mmol hydrogen per 1010 CFU |

[98] |

|

POME |

Acid hydrolysis by HCL (37% v/v) |

Saccharification by Clostridium acetobutylicum (YM1) |

38 °C/5.85 |

108.35 mL H2g−1 |

[99] |

3.4. Biogas Production

Biogas is one of the most promising bioenergy alternatives to replace fossil fuels. It is a mixture of two principal gases, called methane and carbon dioxide. When the share of methane in biogas is more than 40%, it would be highly flammable and could be considered as a renewable energy source [100][101][100,101]. Many renewable sources such as lignocellulosic materials that include agricultural residues can be used to produce biogas due to their potential and characteristics [102]. There are several resources for the production of biogas, including industrial wastewater, urban wastewater, municipal solid waste, and lignocellulosic wastes [103]. Several biomass resources are available in Malaysian industries, such as palm oil, paddy, sugar, and wood. Palm oil industries produce 59.8 million tons of biomass per year, which is the most significant biomass source in Malaysia (Table 5).

Table 5. Various resources of biomass in Malaysia and their estimated energy potential.

|

Industry Type |

Generation (Million tons/year) |

Type of Generated Biomass |

Potential Energy * (Million Tonnes) |

|

Municipal solid waste |

4.35 |

Municipal solid waste |

- |

|

Palm oil |

59.8 |

Empty fruit bunches |

5.53 |

|

Fronds and trunk |

- |

||

|

Fiber |

3.99 |

||

|

Shell |

1.89 |

||

|

Paddy |

2.14 |

Palm kernel |

95 |

|

Rice husk |

0.17 |

||

|

Rice straw |

0.28 |

||

|

Sugar |

1.11 |

Bagasse |

0.069 |

|

Wood |

0.3 |

Plywood residue |

0.024 |

|

1.67 |

Sawdust |

0.44 |

|

|

Stool ** |

N. A. |

Animal wastes |

8.27 × 109 kWh/year |

* Potential energy generated (ton) = residue generated (ton) × 1000 kg × calorific value (kJ/kg)/41,86,8000 kJ. ** The potential of energy generated from stool is 8.27 × 109 kWh/year. Sources: [104][105]

[104,105].

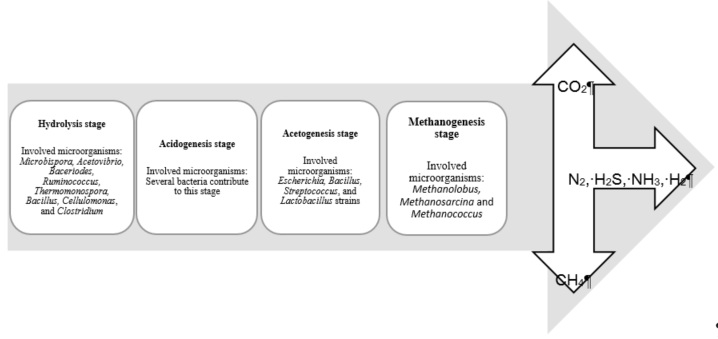

Biogas can be produced in an anaerobic digestion process. Organic compounds are decomposed into simpler compounds by anaerobic microorganisms. Then, in several consequent biological processes, these compounds are converted to final products such as methane, carbon dioxide, hydrogen, nitrogen, and hydrogen sulfide [106][107][108][106–108]. Anaerobic digestion is used to produce biogas from a wide range of materials, such as organic solid waste, agricultural biomass, food, and animal feces [109][104,109]. The biological conversion of biogas from organic wastes to generate bioenergy has several advantages over other forms of energy production from biomass. Those methods could be listed as biological biodiesel production from biomass, the incineration of biomass or biohydrogen, biobutanol, and bioethanol production [110]. Biologically, biogas is produced by a consortium of microorganisms in four stages, called hydrolysis, acidogenesis, acetogenesis, and methanogenesis (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Different stages of the biogas production process and the microorganisms involved in each stage.

The stage of organic waste hydrolysis can be carried out using several strains of bacteria such as Microbispora, Acetovibrio, Bacteriodes, Ruminococcus, Thermomonospora, Bacillus, Cellulomonas, and Clostridium [111]. Methanogenesis microorganisms are sensitive to pH. The optimal pH for methanogenesis microorganisms is from 7.2 to 7.8. In a pH below 6.8, the methane production is stopped by methanogens. The highest biogas production rate is usually between 41 and 43 °C, but can be increased for some substrates in thermophilic fermentation (52 °C to 56 °C) [101]. Table 6 shows recent studies of biogas production from different sources in Malaysia.

Table 6. Recent studies of different biogas production methods from different sources in Malaysia.

|

Feedstock |

Pretreatment Type |

Experiment Condition (Inoculum) |

Hydrolyze and Acetogenesis Stages pH |

Biogas Production Yield (L/g Fresh Mass) |

Reference |

|

Wheat and pearl millet straw |

Biological treatment by Chaetomium globosporum |

1.5 g/L |

6 |

0.568 |

[112] |

|

Oil palm empty fruit bunches |

Prehydrolysis and bioaugmentation |

20.7 g/L |

7.2–7.5 |

0.349 |

[113] |

|

Cow manure |

Physical |

0.5 g/L |

N. A. |

0.27 |

[114] |

|

Food waste |

N. A. |

N. A. |

4.8 |

0.7 |

[115] |

|

POME |

N. A. |

75–80 g/L |

3–3.2 |

0.06 |

[116] |

|

Fresh cow dung |

Physical (chopping) |

N. A. |

7 |

1.1–1.6 |

[117] |

|

Cow manure |

N. A. |

N. A. |

6.23–6.92 |

0.011 |

[118] |

|

A mixture of grass silage, maize silage, hay, straw, molassess, and Bovigold |

Biological pretreatment using Neocallimastix frontalis strains |

N. A. |

N. A. |

0.6 |

[119] |

- A: data not available.