Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by MIguel Angel Galván Morales and Version 4 by Camila Xu.

Programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) and its ligands PD-L1 and PD-L2 are receptors that act in co-stimulatory and coinhibitory immune responses. Signaling the PD-1/PD-L1 or PD-L2 pathway is essential to regulate the inflammatory responses to infections, autoimmunity, and allergies, and it has been extensively studied in cancer.La muerte celular programada 1 (PD-1) y sus ligandos PD-L1 y PD-L2 son receptores que actúan en respuestas inmunitarias coestimuladoras y coinhibidoras. La señalización de la vía PD-1 / PD-L1 o PD-L2 es esencial para regular las respuestas inflamatorias a infecciones, autoinmunidad y alergias, y se ha estudiado ampliamente en el cáncer.

- PD-1

- PD-L1

- PD-L2

- asthma

- BTLA

1. Introduction

1. Introducción [ 1 ] [ 2 ] [ 3 ] [ 4 ] [ 5 ] [ 6 ] [ 7 ] [ 8 ] [ 9 ] [ 10 ] [ 11 ] [ 10 ] [ 12 ] [ 13 ] [ 10 ] [ 14 ] [ 15 ] [ 16 ] [ 17 ] [18 ] [ 19 ] [ 20 ] [ 21 ] [ 22 ] [ 23 ] [ 10 ] [ 24 ] [ 25 ] [ 26 ] [ 27 ] [ 28 ] [ 29 ] [ 30 ] [ 31 ] [ 32 ] [ 33 ] [ 34 ] [ 35 ] [ 36 ] [37 ] [ 38 ] [ 39 ] [ 40 ] [ 41 ] [ 42 ] [ 43 ] [ 44 ] [ 45 ] [ 46 ] [ 47 ] [ 4 ] [ 4 ] [ 10 ] [10 ] [ 25 ] [ 4 ] [ 4 ] [ 48 ] [ 10 ] [ 10 ] [ 4 ] [ 10 ] [ 25 ]

Allergic diseases are characterized by hyperreactive immune responses to otherwise innocuous antigens in the general population, the incidence and prevalence of which are increasing worldwide, particularly in the developed world. In some western countries, every third child needs medical attention from a physician caused by allergic diseases [1][2][3].Las enfermedades alérgicas se caracterizan por respuestas inmunes hiperreactivas a antígenos que de otro modo se encuentran inocuos en la población general, cuya incidencia y prevalencia están aumentando en todo el mundo, particularmente en el mundo desarrollado. En algunos países occidentales, uno de cada tres niños necesita atención médica de un médico a causa de enfermedades alérgicas [ 1 , 2 , 3 ].

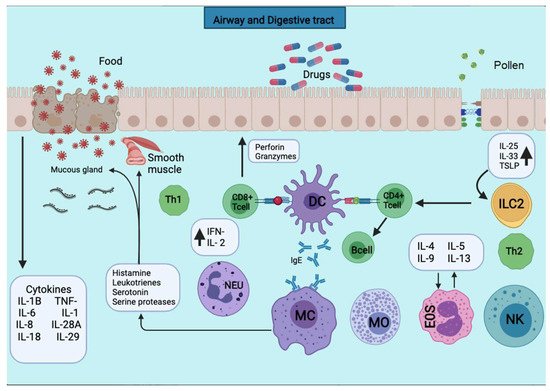

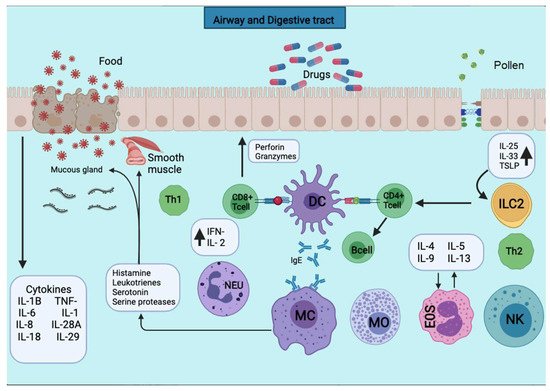

The allergic inflammatory process involves different cell types that release a range of inflammatory mediators and cytokines. Th2 cytokines, including IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13, induce IgE production, while IL-5 promotes eosinophil infiltration [4][5]. Other factors, including Th1 cytokines, may sometimes affect the clinical manifestation creating a potential tolerance induction or hyperactivity [6]. Moreover, the progression of allergy disease is mediated by the innate immune system on the respiratory or gastrointestinal tract mucosa. Indeed, antigen-presenting cells (APCs) become activated, and epithelial alarmins (IL-25, IL-31, IL-33, and TSLP) are released due to activation of the airway epithelial cells in response to allergens [7], leading to activation of Th2/mast cell/eosinophil/eosinophil-mediated allergic pathology, including IL-4 and IL-5. Another pathway is the Th1/Th17/neutrophil-mediated response to chronic innate immune activation and irreversible airway obstruction [8][9]. In addition, the high cellular plasticity in the context of type-2-driven inflammation refers to the capacity of T-helper cell subpopulations to respond depending on environmental signals differentiating into other effector cell types. For example, in chronic asthma, Th1 and Th2 cytokines contribute to airway wall remodeling. Another group of cells that respond to environmental signals are group 2 innate lymphoid cells that exhibit a dynamic phenotype in allergic airway inflammation [10]. Allergic diseases such as asthma are heterogeneous with multiple conditions. The molecular phenotypes defined based on the predominant inflammatory cell are endotypes. In this context, the type 2 immune response can be categorized into different subgroups, such as IL-5-high, IL-13-high, or IgE-high, and others [11].El proceso inflamatorio alérgico involucra diferentes tipos de células que liberan una variedad de mediadores inflamatorios y citocinas. Las citocinas Th2, incluidas IL-4, IL-5 e IL-13, inducen la producción de IgE, mientras que la IL-5 promueve la infiltración de eosinófilos [ 4 , 5 ]. Otros factores, incluidas las citocinas Th1, a veces pueden afectar la manifestación clínica creando una posible inducción de tolerancia o hiperactividad [ 6 ]. Además, la progresión de la enfermedad alérgica está mediada por el sistema inmunitario innato de la mucosa del tracto respiratorio o gastrointestinal.De hecho, las células presentadoras de antígenos (APC) se activan y las alarminas epiteliales (IL-25, IL-31, IL-33 y TSLP) se liberan debido a la activación de las células epiteliales de las vías respiratorias en respuesta a los alérgenos [ 7 ], que conduce a la activación de patología alérgica mediada por Th2 / mastocitos / eosinófilos / eosinófilos, incluidas IL-4 e IL-5. Otra vía es la respuesta mediada por neutrófilos / Th1 / Th17 a la activación inmunitaria innata crónica y la obstrucción irreversible de las vías respiratorias [ 8 , 9 ].Además, la alta plasticidad celular en el contexto de la inflamación impulsada por el tipo 2 se refiere a la capacidad de las subpoblaciones de células T colaboradoras para responder dependiendo de las señales ambientales que se diferencian en otros tipos de células efectoras. Por ejemplo, en el asma crónica, las citocinas Th1 y Th2 contribuyen a la remodelación de la pared de las vías respiratorias. Otro grupo de células que responden a las señales ambientales son las células linfoides innatas del grupo 2 que exhiben un fenotipo dinámico en la inflamación alérgica de las vías respiratorias [ 10]. Las enfermedades alérgicas como el asma son heterogéneas con múltiples afecciones. Los fenotipos moleculares definidos en función de la célula inflamatoria predominante son los endotipos. En este contexto, la respuesta inmune de tipo 2 se puede clasificar en diferentes subgrupos, como IL-5 alta, IL-13 alta o IgE alta, y otros [ 11 ].

In contrast, IL-10 downregulates the inflammatory process. IL-10 acts directly on CD4+ T cells, primarily by down-regulating IL-2 and other cytokines produced by Th1 cells. It also inhibits Th2 cell production of IL-4 and IL-5. On dendritic cells (DCs), monocytes and macrophages, and APCs, the effects of IL-10 include inhibition of the production of free mediator molecules in the medium, such as receptor decreases, or abolished antigen presentation and phagocytosis [12]. Thus, IL-10 plays an essential role as a regulatory molecule in both innate and adaptive immune responses, leading to immune tolerance or dampening tissue inflammation in humans. Similarly, the programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) and its ligands PD-L1 and PD-L2 play an essential role in regulating T cells activation. It controls the immune balance preventing the accumulation of self-reactive T cells [13]. PD-1 has been characterized as a negative regulator of conventional CD4+ T cells. In addition, PD-L1 and PD-L2 have an essential but oppositive role in modulating and polarizing functions of T-cells in hyperreactivity [14].Por el contrario, la IL-10 regula negativamente el proceso inflamatorio. La IL-10 actúa directamente sobre las células T CD4 +, principalmente mediante la regulación negativa de IL-2 y otras citocinas producidas por las células Th1. También inhibe la producción de IL-4 e IL-5 por parte de las células Th2. En las células dendríticas (DC), los monocitos y macrófagos y las APC, los efectos de IL-10 incluyen la inhibición de la producción de moléculas mediadoras libres en el medio, como la disminución del receptor, o la presentación de antígenos y la fagocitosis abolidas [ 12]. Por lo tanto, la IL-10 desempeña un papel esencial como molécula reguladora en las respuestas inmunitarias tanto innatas como adaptativas, lo que conduce a la tolerancia inmunitaria o la atenuación de la inflamación tisular en los seres humanos. De manera similar, la muerte celular programada 1 (PD-1) y sus ligandos PD-L1 y PD-L2 juegan un papel esencial en la regulación de la activación de las células T. Controla el equilibrio inmunológico evitando la acumulación de células T autorreactivas [ 13 ]. El PD-1 se ha caracterizado como un regulador negativo de las células T CD4 + convencionales. Además, PD-L1 y PD-L2 tienen un papel esencial pero opuesto en las funciones de modulación y polarización de las células T en hiperreactividad [ 14 ].

2. PD-1 and Its Ligands PD-L1 and PD-L2

Research on PD-1 and its ligands has been performed mostly in cancer, and allergies have been under-investigated. Honjo and coworkers described PD-1 in 1992 [15]; a few years later, in 1999, its ligand PD-L1 was described by Lieping Chen [16]. PD1 is expressed on several cell types, including activated CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, B cells, natural killers (NKT), monocyte-macrophages, APCs, and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes CD11c+ myeloid DCs [17][18][19]. PD-1 is primarily expressed on thymocytes during embryonic development and on CD4- and CD8- immature lymphocytes. It can also be expressed in naive lymphatic tissues (LTs), dormant LTs, eosinophils, basophils, and mast cells. It can also be expressed in other non-hematopoietic cell lines such as neurons, keratinocytes, endothelial cells, fibroblasts, placenta, retina, and hair follicles [20][21]. The common ɣ-chain cytokines IL-2, IL-7, IL-15, and IL-21, can induce PD-1 expression on T cells [22]. PD-1 has been related as a modulator of immune responses because PD-1–deficient mice developed autoimmune phenotypes [23]; also play a significant role in antigen presentation by DCs to CD8+ T cells by regulating ligand-induced TCR down-modulation [24]. Dong and colleagues described a third member of the B7 family, called B7-H1 (PD-L1). They reported that PD-L1 co-stimulates T cells via a receptor different from CD28, CTLA4, or ICOS (inducible co-stimulator) and delivers an activation signal to T cells [16]. PD-L1 protein is constitutively expressed on hematopoietic and non-hematopoietic cells such as DCs, granulocytes, T cells, B cells, and tumor cells [25][26][27]. In macrophages by LPS, IFN-γ, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and T cells, B cells plus DCs, the expression of PD-1 and its ligands are regulated by proinflammatory cytokines. IFNs, TNF-α. IL-2, IL-7 and IL-10, and IL-15 stimulate PD-L1 expression at the cell membrane. (Figure 1) [18]. A frequent administration of anti-PD-L1, such as atezolizumab, is required for cancer treatment because PD-L1 is high in circulating-myeloid cells [28]. The expression of PD-L1 within non-lymphoid tissues suggests that it may regulate the function of self-reactive immune cells in peripheral tissues or may regulate inflammatory responses [15]. PD-1 is an early brake that fine-tunes T-cell activation during antigen presentation after TCR signal transduction. PD-L1/PD-1 co-stimulation in antigen-presenting DCs contributes to PD-L1-induced TCR down-modulation [24]. Furthermore, PD-L1 stimulates the production of IL-10 by T-cells [16][29]. In contrast to PD-L1, the PD-L2 is rarely expressed on resting cells and can only be induced on DCs, macrophages, and bone marrow-derived cultured mast cells. The regulation of PD-L2 is by IL-4 and GM-CSF. PD-L2 can be induced on macrophages by IL-4 and IFNγ and DCs by anti-CD40, GM-CSF, IL-4, IFN-γ, and IL-12 [18][30].2. PD-1 y sus ligandos PD-L1 y PD-L2

La investigación sobre el PD-1 y sus ligandos se ha realizado principalmente en el cáncer, y las alergias se han investigado poco. Honjo y colaboradores describieron PD-1 en 1992 [ 22 ]; unos años más tarde, en 1999, Lieping Chen describió su ligando PD-L1 [ 23 ]. PD1 se expresa en varios tipos de células, incluidas células T CD4 + y CD8 + activadas, células B, asesinos naturales (NKT), monocitos-macrófagos, APC y linfocitos CD11c + CD mieloides que infiltran tumores [ 24 , 25 , 26]. PD-1 se expresa principalmente en timocitos durante el desarrollo embrionario y en linfocitos inmaduros CD4 y CD8. También se puede expresar en tejidos linfáticos ingenuos (LT), LT latentes, eosinófilos, basófilos y mastocitos. También se puede expresar en otras líneas celulares no hematopoyéticas como neuronas, queratinocitos, células endoteliales, fibroblastos, placenta, retina y folículos pilosos [ 27 , 28 ]. Las citocinas comunes de la cadena ɣ, IL-2, IL-7, IL-15 e IL-21, pueden inducir la expresión de PD-1 en las células T [ 29 ]. El PD-1 se ha relacionado como un modulador de las respuestas inmunitarias porque los ratones deficientes en PD-1 desarrollaron fenotipos autoinmunes [ 30]; también desempeñan un papel importante en la presentación de antígenos por las CD a las células T CD8 + mediante la regulación de la modulación por disminución de TCR inducida por ligando [ 31 ].

Dong y sus colegas describieron un tercer miembro de la familia B7, llamado B7-H1 (PD-L1). Informaron que PD-L1 coestimula las células T a través de un receptor diferente de CD28, CTLA4 o ICOS (coestimulador inducible) y envía una señal de activación a las células T [ 23 ]. La proteína PD-L1 se expresa de forma constitutiva en células hematopoyéticas y no hematopoyéticas como las CD, los granulocitos, las células T, las células B y las células tumorales [ 32 , 33 , 34 ]. En los macrófagos por LPS, IFN-γ, factor estimulante de colonias de granulocitos-macrófagos (GM-CSF) y células T, células B más DC, la expresión de PD-1 y sus ligandos está regulada por citocinas proinflamatorias. IFN, TNF-α. IL-2, IL-7 e IL-10 e IL-15 estimulan la expresión de PD-L1 en la membrana celular. ( Figura 2) [ 25 ]. Se requiere una administración frecuente de anti-PD-L1, como atezolizumab, para el tratamiento del cáncer porque PD-L1 tiene un alto contenido de células mieloides circulantes [ 35 ]. La expresión de PD-L1 en tejidos no linfoides sugiere que puede regular la función de las células inmunitarias autorreactivas en los tejidos periféricos o puede regular las respuestas inflamatorias [ 22 ]. PD-1 es un freno temprano que afina la activación de las células T durante la presentación del antígeno después de la transducción de la señal de TCR. La coestimulación de PD-L1 / PD-1 en las CD presentadoras de antígeno contribuye a la modulación por disminución de TCR inducida por PD-L1 [ 31 ]. Además, PD-L1 estimula la producción de IL-10 por las células T [ 23 , 36]. A diferencia de PD-L1, PD-L2 rara vez se expresa en células en reposo y solo puede inducirse en DC, macrófagos y mastocitos cultivados derivados de la médula ósea. La regulación de PD-L2 es por IL-4 y GM-CSF. PD-L2 puede inducirse en macrófagos por IL-4 e IFNγ y CD por anti-CD40, GM-CSF, IL-4, IFN-γ e IL-12 [ 25 , 37 ].

Figure 1. APCs present the antigens to the CD4+ T cells subpopulation for activation. APCs take up the first sensitizing contact with the antigen, bind it to MHC class II molecules, and expose it to the membrane. APCs take up the first sensitizing contact with the antigen, which processes and binds it to MHC class II molecules and exposes it to the membrane. Several cytokines such as TNF-a, IL-1, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-13, MIP-1a, and various colony-stimulating factors such as GM-CSF and IL-3 are released. The triggering of the allergic reaction is stimulated by the production of IgE by B lymphocytes. The production of IgE stimulates the triggering of the allergic reaction by B lymphocytes. The IgE will bind to mast cells and basophils for degranulation and the release of several mediators.Figura 2. Las APC presentan los antígenos a la subpoblación de células T CD4 + para su activación. Las APC toman el primer contacto de sensibilización con el antígeno, lo unen a las moléculas del MHC de clase II y lo exponen a la membrana. Las APC toman el primer contacto sensibilizante con el antígeno, que lo procesa y lo une a las moléculas del MHC de clase II y lo expone a la membrana. Se liberan varias citocinas como TNF-a, IL-1, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-13, MIP-1a y varios factores estimulantes de colonias como GM-CSF e IL-3. El desencadenamiento de la reacción alérgica es estimulado por la producción de IgE por los linfocitos B. La producción de IgE estimula el desencadenamiento de la reacción alérgica por parte de los linfocitos B. La IgE se unirá a los mastocitos y basófilos para la desgranulación y la liberación de varios mediadores.

La expresión de PD-L1 y PD-L2 depende de distintos estímulos, y sus patrones de expresión sugieren funciones tanto superpuestas como diferenciales en la regulación inmunitaria [ 38 , 39 ]. Estos nuevos datos sugieren resultados opuestos informados con respecto a la función PD-1 [ 40 ]. Muchas citocinas juegan un papel esencial en la inducción o el mantenimiento de la expresión de PD-L1. Estudios in vitro e in vivo han demostrado que la expresión de la proteína PD-L1 en APC, linfocitos T reguladores y células cancerosas dependía fuertemente de la existencia de citocinas proinflamatorias: IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6, también como IL-2, IL-7, IL-15 e IL-21. Además, los IFN de tipo I y tipo II son el segundo mecanismo impulsado por los oncogenes (cascada de ciclina D-CDK4) [ 36 , 41 , 42, 43 , 44 ]. La función de PD-L1 es mantener la tolerancia periférica y contribuir a la presentación de antígenos a las células T por las células dendríticas [ 42 ]. PD-L1 se regula al alza en respuesta a la inflamación y suprime las respuestas inmunitarias excesivas, lo que puede causar una lesión tisular innecesaria. Las células tumorales que surgen de células normales adoptan este mecanismo para evadir la inmunidad tumoral. Supresión de linfocitos T para PD-L1 en el microambiente tumoral. Del mismo modo, PD-L1 se regula al alza para inhibir la apoptosis en muchas células y regular el metabolismo de la glucosa [ 45 , 46 ]. El PD-1 y sus ligandos parecen desempeñar un papel esencial en el mantenimiento de la homeostasis de las células T en el cáncer y las enfermedades alérgicas.

PD-L1 and PD-L2 expression depend on distinct stimuli, and their expression patterns suggest both overlapping and differential roles in immune regulation [31][32]. These new data suggest opposing results reported regarding the PD-1 function [33]. Many cytokines play an essential role in inducing or maintaining PD-L1 expression. Both in vitro and in vivo studies have proved that the expression of PD-L1 protein in APCs, regulatory T lymphocytes, and cancer cells strongly relied on the existence of proinflammatory cytokines: IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6, as well as IL-2, IL-7, IL-15, and IL-21. Furthermore, IFNs type I and type II are the second mechanisms driven by oncogenes (cyclin D-CDK4 cascade) [29][34][35][36][37]. The role of PD-L1 is to maintain peripheral tolerance and contribute to antigen presentation to T cells by dendritic cells [35]. PD-L1 is up-regulated in response to inflammation and suppresses excessive immune responses, which may cause unnecessary tissue injury. Tumor cells that arise from normal cells adopt this mechanism to evade tumor immunity. T-lymphocyte suppression for PD-L1 in the tumor microenvironment. Likewise, PD-L1 up-regulated to inhibit apoptosis in many cells and regulate glucose metabolism [38][39]. PD-1 and its ligands appear to play an essential role in maintaining T cell homeostasis in cancer and allergic diseases.

3. PD-1 and Its Ligands in Allergy Diseases

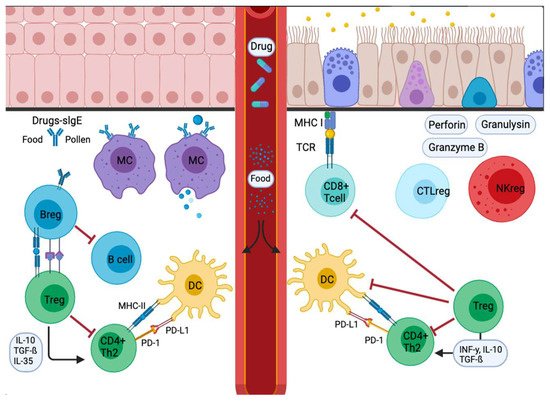

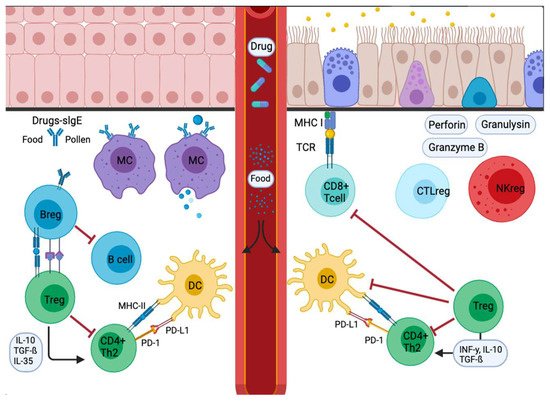

The type 2 immune response represents the main and the most clinically relevant immune response in allergic diseases. PD-1 and its ligands have an essential role in maintaining T cell homeostasis via regulatory T- B-cells (Tregs and Bregs) (Figure 2) [40].3. PD-1 y sus ligandos en las enfermedades alérgicas

La respuesta inmune de tipo 2 representa la respuesta inmune principal y clínicamente más relevante en las enfermedades alérgicas. PD-1 y sus ligandos tienen un papel esencial en el mantenimiento de la homeostasis de las células T a través de las células T-B reguladoras (Tregs y Bregs) ( Figura 3 ) [ 47 ]. La siguiente sección resume los nuevos conocimientos de PD-1 y sus ligandos, PD-L1 y PD-L2, en enfermedades alérgicas que incluyen asma alérgica, respuesta inmune de la piel, rinoconjuntivitis, alergia alimentaria y anafilaxia.

Figure 2. Signal inflammatory cascade allergy response in mucosas. Incoming allergens are taken up and processed by APCs or antibodies. Allergens cross the mucosa, then move to the lung pleura or intestine. In the sensitization stage, APCs present the antigen and give an immediate response. Others migrate to the draining lymph nodes, where the processed allergen is presented to naïve T and B cells, responses characterized and influenced by the cytokines secreted and the presence or absence of cell-bound co-stimulatory molecules. Decreased stimulus and/or the presence of IL-10, IL-35, or TGF-β triggers Treg cell transformation. In addition, APCs lead to the production of cytokines that regulate the change and expression of coinhibitory receptors such as PD1/PD-L1.Figura 3. Señal de respuesta alérgica en cascada inflamatoria en mucosas. Los alérgenos entrantes son absorbidos y procesados por APC o anticuerpos. Los alérgenos atraviesan la mucosa y luego se trasladan a la pleura pulmonar o al intestino. En la etapa de sensibilización, las APC presentan el antígeno y dan una respuesta inmediata. Otros migran a los ganglios linfáticos de drenaje, donde el alérgeno procesado se presenta a las células T y B vírgenes, con respuestas caracterizadas e influenciadas por las citocinas secretadas y la presencia o ausencia de moléculas coestimuladoras unidas a las células. La disminución del estímulo y / o la presencia de IL-10, IL-35 o TGF-β desencadenan la transformación de las células Treg. Además, las APC conducen a la producción de citocinas que regulan el cambio y la expresión de receptores coinhibidores como PD1 / PD-L1.

References

- Han, X.; Krempski, J.W.; Nadeau, K. Advances and novel developments in mechanisms of allergic inflammation. Allergy 2020, 75, 3100–3111. Han, X.; Krempski, J.W.; Nadeau, K. Advances and novel developments in mechanisms of allergic inflammation. Allergy 2020, 75,

- Siracusa, M.C.; Kim, B.S.; Spergel, J.M.; Artis, D. Basophils and allergic inflammation. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2013, 132, 789–801. 3100–3111. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van de Veen, W.; Wirz, O.F.; Globinska, A.; Akdis, M. Novel mechanisms in immune tolerance to allergens during natural allergen exposure and allergen-specific immunotherapy. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2017, 48, 74–81. Siracusa, M.C.; Kim, B.S.; Spergel, J.M.; Artis, D. Basophils and allergic inflammation. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2013, 132, 789–801.

- Stock, P.; DeKruyff, R.H.; Umetsu, D.T. Inhibition of the allergic response by regulatory T cells. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2006, 6, 12–16. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansbro, P.M.; Kaiko, G.E.; Foster, P.S. Cytokine/anti-cytokine therapy-novel treatments for asthma? Br. J. Pharmacol. 2011, 163, 81–95. van de Veen, W.; Wirz, O.F.; Globinska, A.; Akdis, M. Novel mechanisms in immune tolerance to allergens during natural allergen

- Wing, K.; Sakaguchi, S. Regulatory T cells as potential immunotherapy in allergy. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2006, 6, 482–488. exposure and allergen-specific immunotherapy. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2017, 48, 74–81. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Li, Y.; Lv, Z.; Chen, Y.; Li, Y.; Huang, K.; Corrigan, C.J.; Ying, S. Bronchial Allergen Challenge of Patients with Atopic Asthma Triggers an Alarmin (IL-33, TSLP, and IL-25) Response in the Airways Epithelium and Submucosa. J. Immunol. 2018, 201, 2221–2231. Stock, P.; DeKruyff, R.H.; Umetsu, D.T. Inhibition of the allergic response by regulatory T cells. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol.

- Gubernatorova, E.O.; Namakanova, O.A.; Tumanov, A.V.; Drutskaya, M.S.; Nedospasov, S.A. Mouse models of severe asthma for evaluation of therapeutic cytokine targeting. Immunol. Lett. 2019, 207, 73–83. 2006, 6, 12–16. [CrossRef]

- Gubernatorova, E.O.; Namakanova, O.A.; Gorshkova, E.A.; Medvedovskaya, A.D.; Nedospasov, S.A.; Drutskaya, M.S. Novel Anti-Cytokine Strategies for Prevention and Treatment of Respiratory Allergic Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 1704. Hansbro, P.M.; Kaiko, G.E.; Foster, P.S. Cytokine/anti-cytokine therapy-novel treatments for asthma? Br. J. Pharmacol. 2011, 163, 81–95.

- Kuruvilla, M.E.; Lee, F.E.-H.; Lee, G.B. Understanding Asthma Phenotypes, Endotypes, and Mechanisms of Disease. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2019, 56, 219–233. [CrossRef]

- Agache, I.; Sugita, K.; Morita, H.; Akdis, M.; Akdis, C.A. The Complex Type 2 Endotype in Allergy and Asthma: From Laboratory to Bedside. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2015, 15, 29. Wing, K.; Sakaguchi, S. Regulatory T cells as potential immunotherapy in allergy. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2006, 6, 482–488.

- Mittal, S.K.; Roche, P.A. Suppression of antigen presentation by IL-10. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2015, 34, 22–27. Wang, W.; Li, Y.; Lv, Z.; Chen, Y.; Li, Y.; Huang, K.; Corrigan, C.J.; Ying, S. Bronchial Allergen Challenge of Patients with Atopic Asthma

- Canavan, M.; Floudas, A.; Veale, D.J.; Fearon, U. The PD-1:PD-L1 axis in Inflammatory Arthritis. BMC Rheumatol. 2021, 5, 1. Triggers an Alarmin (IL-33, TSLP, and IL-25) Response in the Airways Epithelium and Submucosa. J. Immunol. 2018, 201, 2221–2231.

- Schwamborn, K. Imaging mass spectrometry in biomarker discovery and validation. J. Proteomics 2012, 75, 4990–4998. Gubernatorova, E.O.; Namakanova, O.A.; Tumanov, A.V.; Drutskaya, M.S.; Nedospasov, S.A. Mouse models of severe asthma for

- Ishida, Y.; Agata, Y.; Shibahara, K.; Honjo, T. Induced expression of PD-1, a novel member of the immunoglobulin gene superfamily, upon programmed cell death. EMBO J. 1992, 11, 3887–3895. evaluation of therapeutic cytokine targeting. Immunol. Lett. 2019, 207, 73–83. [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Zhu, G.; Tamada, K.; Chen, L. B7-H1, a third member of the B7 family, co-stimulates T-cell proliferation and interleukin-10 secretion. Nat. Med. 1999, 5, 1365–1369. Gubernatorova, E.O.; Namakanova, O.A.; Gorshkova, E.A.; Medvedovskaya, A.D.; Nedospasov, S.A.; Drutskaya, M.S. Novel

- Agata, Y.; Kawasaki, A.; Nishimura, H.; Ishida, Y.; Tsubat, T.; Yagita, H.; Honjo, T. Expression of the PD-1 antigen on the surface of stimulated mouse T and B lymphocytes. Int. Immunol. 1996, 8, 765–772. Anti-Cytokine Strategies for Prevention and Treatment of Respiratory Allergic Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 1704. [CrossRef]

- Yamazaki, T.; Akiba, H.; Iwai, H.; Matsuda, H.; Aoki, M.; Tanno, Y.; Shin, T.; Tsuchiya, H.; Pardoll, D.M.; Okumura, K.; et al. Expression of Programmed Death 1 Ligands by Murine T Cells and APC. J. Immunol. 2002, 169, 5538–5545. Kuruvilla, M.E.; Lee, F.E.-H.; Lee, G.B. Understanding Asthma Phenotypes, Endotypes, and Mechanisms of Disease. Clin. Rev.

- Boussiotis, V.A. Molecular and Biochemical Aspects of the PD-1 Checkpoint Pathway. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 1767–1778. Allergy Immunol. 2019, 56, 219–233. [CrossRef]

- Petrovas, C.; Casazza, J.P.; Brenchley, J.M.; Price, D.A.; Gostick, E.; Adams, W.C.; Precopio, M.L.; Schacker, T.; Roederer, M.; Douek, D.C.; et al. PD-1 is a regulator of virus-specific CD8+ T cell survival in HIV infection. J. Exp. Med. 2006, 203, 2281–2292. Agache, I.; Sugita, K.; Morita, H.; Akdis, M.; Akdis, C.A. The Complex Type 2 Endotype in Allergy and Asthma: From Laboratory

- Rodrigues, T.B.; Ballesteros, P. Journal of Neuroscience Research 85:3244–3253 (2007). J. Neurosci. Res. 2007, 3253, 3244–3253. to Bedside. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2015, 15, 29. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinter, A.L.; Godbout, E.J.; McNally, J.P.; Sereti, I.; Roby, G.A.; O’Shea, M.A.; Fauci, A.S. The Common γ-Chain Cytokines IL-2, IL-7, IL-15, and IL-21 Induce the Expression of Programmed Death-1 and Its Ligands. J. Immunol. 2008, 181, 6738 LP–6746. Mittal, S.K.; Roche, P.A. Suppression of antigen presentation by IL-10. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2015, 34, 22–27. [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, H.; Nose, M.; Hiai, H.; Minato, N.; Honjo, T. Development of lupus-like autoimmune diseases by disruption of the PD-1 gene encoding an ITIM motif-carrying immunoreceptor. Immunity 1999, 11, 141–151. Canavan, M.; Floudas, A.; Veale, D.J.; Fearon, U. The PD-1:PD-L1 axis in Inflammatory Arthritis. BMC Rheumatol. 2021, 5, 1.

- Karwacz, K.; Bricogne, C.; MacDonald, D.; Arce, F.; Bennett, C.L.; Collins, M.; Escors, D. PD-L1 co-stimulation contributes to ligand-induced T cell receptor down-modulation on CD8+ T cells. EMBO Mol. Med. 2011, 3, 581–592. Schwamborn, K. Imaging mass spectrometry in biomarker discovery and validation. J. Proteomics 2012, 75, 4990–4998. [CrossRef]

- Peng, Q.; Qiu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, Y.; Guo, J.; Peng, H.; Chen, M.; Fu, Y.X.; et al. PD-L1 on dendritic cells attenuates T cell activation and regulates response to immune checkpoint blockade. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1–8. [PubMed]

- Nguyen, L.T.; Ohashi, P.S. Clinical blockade of PD1 and LAG3--potential mechanisms of action. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2015, 15, 45–56. Okuyama, Y.; Nagashima, H.; Ushio-Fukai, M.; Croft, M.; Ishii, N.; So, T. IQGAP1 restrains T-cell cosignaling mediated by OX40.

- Sharpe, A.H.; Wherry, E.J.; Ahmed, R.; Freeman, G.J. The function of programmed cell death 1 and its ligands in regulating autoimmunity and infection. Nat. Immunol. 2007, 8, 239–245. FASEB J. 2020, 34, 540–554. [CrossRef]

- Bocanegra, A.; Fernandez-Hinojal, G.; Zuazo-Ibarra, M.; Arasanz, H.; Garcia-Granda, M.; Hernandez, C.; Ibañez, M.; Hernandez-Marin, B.; Martinez-Aguillo, M.; Lecumberri, M.; et al. PD-L1 Expression in Systemic Immune Cell Populations as a Potential Predictive Biomarker of Responses to PD-L1/PD-1 Blockade Therapy in Lung Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1631. Agache, I.; Akdis, C.A. Precision medicine and phenotypes, endotypes, genotypes, regiotypes, and theratypes of allergic diseases.

- Escors, D.; Gato-Cañas, M.; Zuazo, M.; Arasanz, H.; García-Granda, M.J.; Vera, R.; Kochan, G. The intracellular signalosome of PD-L1 in cancer cells. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2018, 3, 26. J. Clin. Invest. 2019, 129, 1493–1503. [CrossRef]

- Nakae, S.; Suto, H.; Iikura, M.; Kakurai, M.; Sedgwick, J.D.; Tsai, M.; Galli, S.J. Mast Cells Enhance T Cell Activation: Importance of Mast Cell Costimulatory Molecules and Secreted TNF. J. Immunol. 2006, 176, 2238–2248. Alarcón, B.; Mestre, D.; Martínez-Martín, N. The immunological synapse: A cause or consequence of T-cell receptor triggering?

- Ghiotto, M.; Gauthier, L.; Serriari, N.; Pastor, S.; Truneh, A.; Nunès, J.A.; Olive, D. PD-L1 and PD-L2 differ in their molecular mechanisms of interaction with PD-1. Int. Immunol. 2010, 22, 651–660. Immunology 2011, 133, 420–425. [CrossRef]

- Loke, P.; Allison, J.P. PD-L1 and PD-L2 are differentially regulated by Th1 and Th2 cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 5336–5341. Yokosuka, T.; Saito, T. The immunological synapse, TCR microclusters, and T cell activation. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2010,

- Butte, M.J.; Keir, M.E.; Phamduy, T.B.; Sharpe, A.H.; Freeman, G.J. Programmed death-1 ligand 1 interacts specifically with the B7-1 costimulatory molecule to inhibit T cell responses. Immunity 2007, 27, 111–122. 340, 81–107. [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Diaz, A.; Shin, D.S.; Moreno, B.H.; Saco, J.; Escuin-Ordinas, H.; Rodriguez, G.A.; Zaretsky, J.M.; Sun, L.; Hugo, W.; Wang, X.; et al. Interferon Receptor Signaling Pathways Regulating PD-L1 and PD-L2 Expression. Cell Rep. 2017, 19, 1189–1201. Kucuksezer, U.C.; Ozdemir, C.; Cevhertas, L.; Ogulur, I.; Akdis, M.; Akdis, C.A. Mechanisms of allergen-specific immunotherapy

- Gato-Cañas, M.; Zuazo, M.; Arasanz, H.; Ibañez-Vea, M.; Lorenzo, L.; Fernandez-Hinojal, G.; Vera, R.; Smerdou, C.; Martisova, E.; Arozarena, I.; et al. PDL1 Signals through Conserved Sequence Motifs to Overcome Interferon-Mediated Cytotoxicity. Cell Rep. 2017, 20, 1818–1829. and allergen tolerance. Allergol. Int. 2020, 69, 549–560. [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Mezzadra, R.; Schumacher, T.N. Regulation and Function of the PD-L1 Checkpoint. Immunity 2018, 48, 434–452. Stone, S.F.; Phillips, E.J.; Wiese, M.D.; Heddle, R.J.; Brown, S.G.A. Immediate-type hypersensitivity drug reactions. Br. J. Clin.

- Francisco, L.M.; Sage, P.T.; Sharpe, A.H. The PD-1 pathway in tolerance and autoimmunity. Immunol. Rev. 2010, 236, 219–242. Pharmacol. 2014, 78, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Liang, Y.; Li, D.; Wang, L.; Liang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Ma, G.; Wu, H.; Jiao, W.; Niu, H. Glucose metabolism involved in PD-L1-mediated immune escape in the malignant kidney tumour microenvironment. Cell Death Discov. 2021, 7, 15. Jubel, J.M.; Barbati, Z.R.; Burger, C.; Wirtz, D.C.; Schildberg, F.A. The Role of PD-1 in Acute and Chronic Infection; Frontiers:

- Eppihimer, M.J.; Gunn, J.; Freeman, G.J.; Greenfield, E.A.; Chernova, T.; Erickson, J.; Leonard, J.P. Expression and regulation of the PD-L1 immunoinhibitory molecule on microvascular endothelial cells. Microcirculation 2002, 9, 133–145. Lausanne, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 11, p. 487.

- Palomares, O.; Akdis, M.; Martín-Fontecha, M.; Akdis, C.A. Mechanisms of immune regulation in allergic diseases: The role of regulatory T and B cells. Immunol. Rev. 2017, 278, 219–236. Ishida, Y.; Agata, Y.; Shibahara, K.; Honjo, T. Induced expression of PD-1, a novel member of the immunoglobulin gene

- superfamily, upon programmed cell death. EMBO J. 1992, 11, 3887–3895. [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Zhu, G.; Tamada, K.; Chen, L. B7-H1, a third member of the B7 family, co-stimulates T-cell proliferation and interleukin10 secretion. Nat. Med. 1999, 5, 1365–1369. [CrossRef]

- Agata, Y.; Kawasaki, A.; Nishimura, H.; Ishida, Y.; Tsubat, T.; Yagita, H.; Honjo, T. Expression of the PD-1 antigen on the surface

- of stimulated mouse T and B lymphocytes. Int. Immunol. 1996, 8, 765–772. [CrossRef]

- Yamazaki, T.; Akiba, H.; Iwai, H.; Matsuda, H.; Aoki, M.; Tanno, Y.; Shin, T.; Tsuchiya, H.; Pardoll, D.M.; Okumura, K.; et al.

- Expression of Programmed Death 1 Ligands by Murine T Cells and APC. J. Immunol. 2002, 169, 5538–5545. [CrossRef]

- Boussiotis, V.A. Molecular and Biochemical Aspects of the PD-1 Checkpoint Pathway. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 1767–1778.

- mechanisms of interaction with PD-1. Int. Immunol. 2010, 22, 651–660. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

More