Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 4 by Anthony Cannavicci and Version 6 by Peter Tang.

Non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) are functional ribonucleic acid (RNA) species that include microRNAs (miRs), a class of short non-coding RNAs (∼21–25 nucleotides), and long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) consisting of more than 200 nucleotides. They regulate gene expression post-transcriptionally and are involved in a wide range of pathophysiological processes. Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT) is a rare disorder inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion characterized by vascular dysplasia. Patients can develop life-threatening vascular malformations and experience severe hemorrhaging.

- non-coding RNAs

- microRNAs

- long non-coding RNAs

- hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia

- biomarkers

- endothelial cells

- angiogenesis

1. Introduction

Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT) is a rare genetic vascular disorder inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion. On average, approximately one in 5000 to 8000 people are affected, while the founder effect has contributed to a higher prevalence in certain regions, such as the Netherlands Antilles, Jura in France and Funen in Denmark [1]. Vascular malformations in HHT include skin and mucocutaneous telangiectasias, and pulmonary, cerebral, hepatic and spinal arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) [2][3][2,3], all of which are susceptible to rupture with resultant spontaneous hemorrhage. Epistaxis is the most common symptom and is present in approximately 95% of patients [4][5][4,5]. HHT is a progressive disorder with significant morbidities and mortality, and lacks a universally effective pharmacological therapy [2].

HHT is caused by heterozygous mutations in at least three known genes: endoglin (ENG, chromosomal locus 9q34) [6], activin receptor-like kinase 1 (ACVRL1, also known as ALK1, chromosomal locus 12q1) [7] and mothers against decapentaplegic homolog 4 (SMAD4, chromosomal locus 18q21) [8]. Each gene encodes for a protein in the transforming growth factor beta (TGFβ)/bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling pathway. This pathway is responsible for many cellular functions, including growth, differentiation and apoptosis, and is critical in angiogenesis and normal endothelial cell (EC) function [9]. The pathogenic role of these genes has been demonstrated in the adult mouse where the homozygous knockout of ENG, ACVRL1 or SMAD4 resulted in various vascular defects, including AVMs [10][11][10,11]. ENG encodes for a TGFβ co-receptor that enhances the affinity of ligand binding to TGFβI and II receptors. This co-receptor is predominately expressed on the endothelium, activated monocytes and macrophages [2]. ACVRL1 encodes for a TGFβ1 receptor that is predominately expressed on endothelial, lung and placental cells [2]. Mutations in ENG and ACVRL1 result in HHT1 and HHT2, respectively, and on average display distinct clinical manifestations, but overlap is not uncommon. Sabbà et al. demonstrated a higher prevalence of pulmonary (75.5% vs. 44.1%) and cerebral AVMs (20.9% vs. 0%) in HHT1, while liver manifestations were higher in HHT2 (83.1% vs. 60%) [12]. SMAD4 is a signal transducer in the TGFβ signaling pathway that directly regulates gene expression. Mutations in SMAD4 not only result in HHT, but juvenile polyposis (JP), culminating in a combined syndrome designated as JP/HHT [8]. ENG and ACVRL1 mutations are responsible for 90% of HHT cases, while SMAD4 contributes to only 2% [13][14][13,14]. A small percentage of cases have been attributed to novel disease loci, HHT 3 (chromosomal locus 5q31) [15] and HHT 4 (chromosomal locus 7p14) [16], but these genes have yet to be identified. Over 700 pathogenic mutations have been identified in ENG and ACVRL1 patients (https://arup.utah.edu/database/HHT/, access date: 20/04/2020), comprising single base pair changes, large deletions, duplications, substitutions and missense mutations [13][17][13,17]. Interestingly, disease severity and the presentation of clinical manifestations vary drastically between patients and this is further demonstrated in affected family members. This discrepancy suggests that the genetic mutations alone are not entirely responsible for disease characteristics and raises the question: what other biological factors could be at play?

Non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) are functional ribonucleic acid (RNA) sequences that are transcribed from DNA, but not translated into protein. NcRNAs can be divided into three categories based on their length: (1) ncRNAs longer than 200 nucleotides (nts), including ribosomal RNA (rRNA), long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) and circular RNA (circRNA); (2) ncRNAs shorter than 200 nts, but longer than 40 nts, such as transfer RNA (tRNA), small nucleolar RNA (snoRNA), Ro-associated Y RNA (YRNA) and small nuclear ribonucleic acid RNA (snRNA); and (3) ncRNA shorter than 40 nts like microRNA (miRNA), piwi-interacting RNA (piRNA), short interfering RNA (siRNA) and tRNA-derived small RNA (tsRNA) [18]. NcRNAs regulate gene expression at the transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels, and are involved in a wide array of cellular processes. In particular, snRNAs and snoRNAs are involved in mRNA maturation; rRNAs and tRNAs are important components for protein translation and miRNAs, piRNAs and lncRNAs are involved in the regulation of target gene expression.

2. MiR Biogenesis and Mechanisms of Action

Nearly half of all identified miRs are expressed from specific genes with their own promoters, with the remainder from protein-coding genes [19][20][19,20]. Additionally, multiple miRs may be expressed as a single transcript, defined as families or clusters, and share similar target homology [21]. Canonical miR biogenesis is initiated with miR gene transcription by an RNA polymerase II [22]. The result is an ~80 nucleotide stem–loop structure called a primary miR (pri-miR) [23]. The pri-miR is further processed by an RNase III enzyme and a double-stranded RNA-binding protein (dsRBP), called Drosha and DGCR8, respectively [23]. This complex shortens the pri-miR to ~70 nts to generate the pre-miR. The pre-miR is exported from the nucleus to the cytoplasm where it is once again processed by an RNase III enzyme and dsRBP, Dicer and transactivation-responsive (TAR) RNA-binding protein (TRBP), respectively, effectively removing the hairpin to produce a miR–miR duplex [23][24][23,24]. The duplex comprises a passenger strand and a guide strand. The passenger strand is degraded, while the guide strand is incorporated into the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC). Strand incorporation is dependent on the thermodynamic stability of the 5′ end of the miR–miR duplex, where the less stable strand is incorporated [25]. RISC contains an RNA binding protein responsible for miR silencing activity, Argonaute 2 (AGO2). AGO2 has potent RNase-H-like endonuclease activity and is capable of cleaving mRNAs [26].

MiRs guide the RISC–AGO complex to target mRNAs by recognizing the miR response element (MRE) in the 3′ untranslated region (UTR) [27][28][27,28]. Alterative binding sites have been identified in the 5′ UTR, coding sequences and within promoter regions [28]. Base pair complementarity between miRs and MREs dictates the mode of gene silencing. Perfect complementarity activates AGO2′s endonuclease activity, resulting in the cleavage and subsequent degradation of target mRNAs [26]. However, in metazoans, this rarely occurs and the majority of miR–MRE interactions are not perfectly complementary [29]. In this scenario, translational inhibition can occur where the miR–RISC–AGO complex likely blocks translational machinery from binding. Alternatively, proteins in complex with AGO2 can recruit poly(A)-deadenylases to elicit mRNA degradation [29]. In this way, miRs can regulate the expression of tens to hundreds of mRNAs. Bioinformatic analyses can use algorithms to predict complementarity for the identification of hundreds of mRNA targets per miR, but realistically only a small subset are experimentally validated [30]. It is important to note that individual miR activity is dependent on several factors, including miR tissue expression profiles (tissue-specific vs. housekeeping) and miR expression levels. Typically, higher miR expression will have a more robust effect on target mRNAs.

3. Circulating MiR Biomarkers in HHT

The discovery of circulating miRs was achieved by several groups [31][32][33][31,32,33], most notably by Chim et al. who identified that stable plasma miRs could distinguish between pregnant and non-pregnant women [34]. Since then, circulating miRs have been established as stable and sensitive candidate biomarkers for various diseases, including cancers, cardiovascular diseases and neurological disorders [35][36][37][38][35,36,37,38]. The stability of circulating miRs can be attributed to their association with proteins such as AGO2 [39] and lipoproteins [40] or their containment in extracellular vesicles [41]. In this way, miRs are shielded from RNase enzymes and are stable in blood for up to 24 h [42]. Changes in circulating miR levels have been shown to be extremely sensitive to disease conditions and can outperform conventional biomarkers. For example, changes in circulating miR levels in response to disease states have been shown to be more rapid than those of mRNAs or proteins [38][43][38,43]. Oerlemans et al. demonstrated that changes in circulating miRs were detected earlier compared with that of troponin for the diagnosis and management of acute coronary syndrome [44].

HHT is diagnosed in combination by a clinical criteria known as the Curaçao criteria [45] and the molecular detection of known genetic mutations. Due to loci heterogeneity, technical challenges of molecular diagnostic techniques and de novo mutations, a clinical diagnosis is always required [45]. Additional biomarkers would greatly improve the diagnostic process as HHT is actually underdiagnosed [46]; they could also aid in the detection and management of clinical manifestations. The detection of AVMs is critical for the management of patient well-being. Approximately 50% of patients develop pulmonary AVMs (PAVMs), 80% develop hepatic AVMs (HAVMs), 10% develop cerebral AVMs (CAVMs) and 1% develop spinal AVMs (SAVMs) [2][47][2,47]. All AVMs are susceptible to rupture that can cause numerous life-threatening complications, including hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke, air embolism, congestive heart failure, cerebral abscess and seizure [47][48][47,48]. The timely detection of AVMs is critical to prevent serious and life-threatening complications, but current diagnostic screens are costly, relatively inaccessible and expose patients to unhealthy doses of radiation [49]. Circulating miRs could potentially provide a rapid, inexpensive, safe and relatively non-invasive screening test for the diagnosis of AVMs.

4. MiRs as Pathogenic Factors in HHT

MiRs have been demonstrated to play a pathogenic role in a variety of human diseases, including cancer, cardiovascular disease, autoimmune diseases and inflammatory diseases [50][51][50,51]. MiR profiling analyses have identified a plethora of up- and downregulated miRs in numerous types of cancers [52]. It has been shown that overexpressed miRs can act as “oncomiRs” by targeting tumor suppressors or by promoting proliferation and inhibiting apoptosis [53]. Additionally, the downregulation of certain “tumor suppressor” miRs, such as let-7, can also contribute to cancer pathogenesis [54][55][54,55]. A growing class of miRs known as “angio-miRs”, predominately expressed in ECs and responsible for the regulation of angiogenic processes, have also been shown to contribute to cancer and cardiovascular disease [56]. Given that HHT is a disorder characterized by angiogenic and EC dysfunction, it would not be surprising if dysregulated “angio-miRs” played a role in disease pathogenesis. There are numerous studies that have identified the involvement of miRs in TGFβ signaling. They have demonstrated that various components of the TGFβ pathway are targeted by miRs and that the pathway itself regulates miR biogenesis [57].5. LncRNAs and HHT

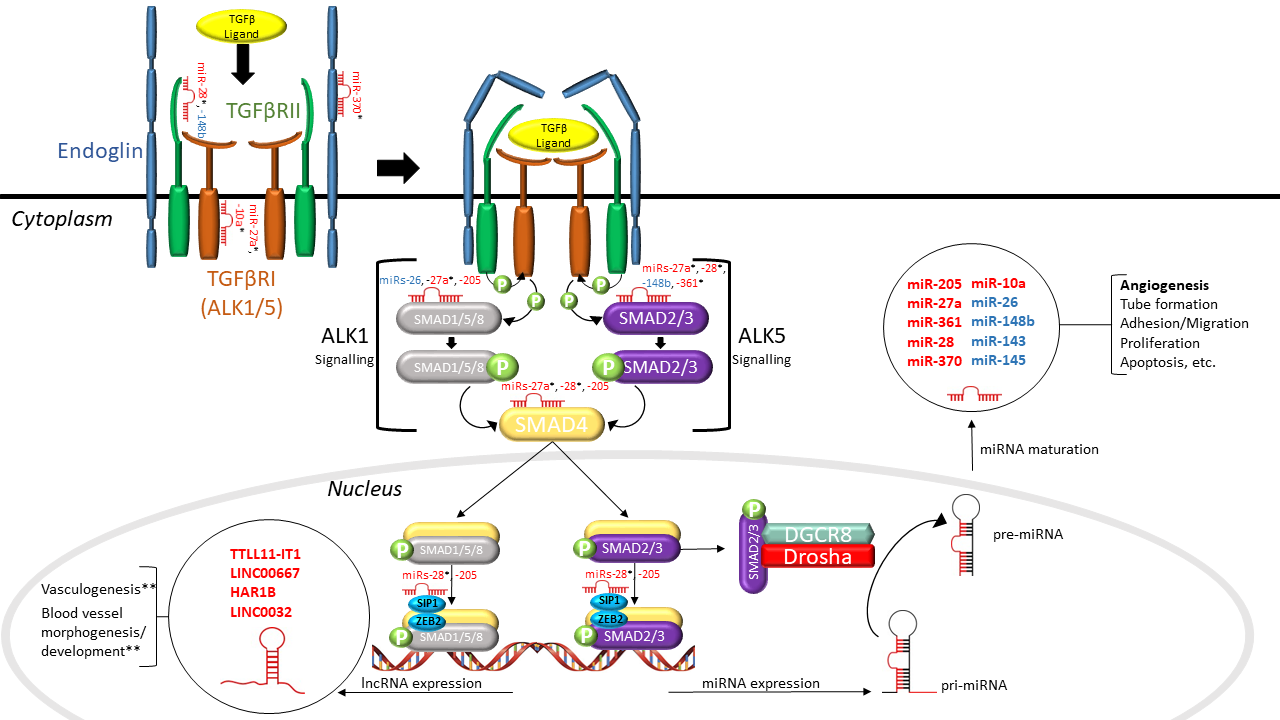

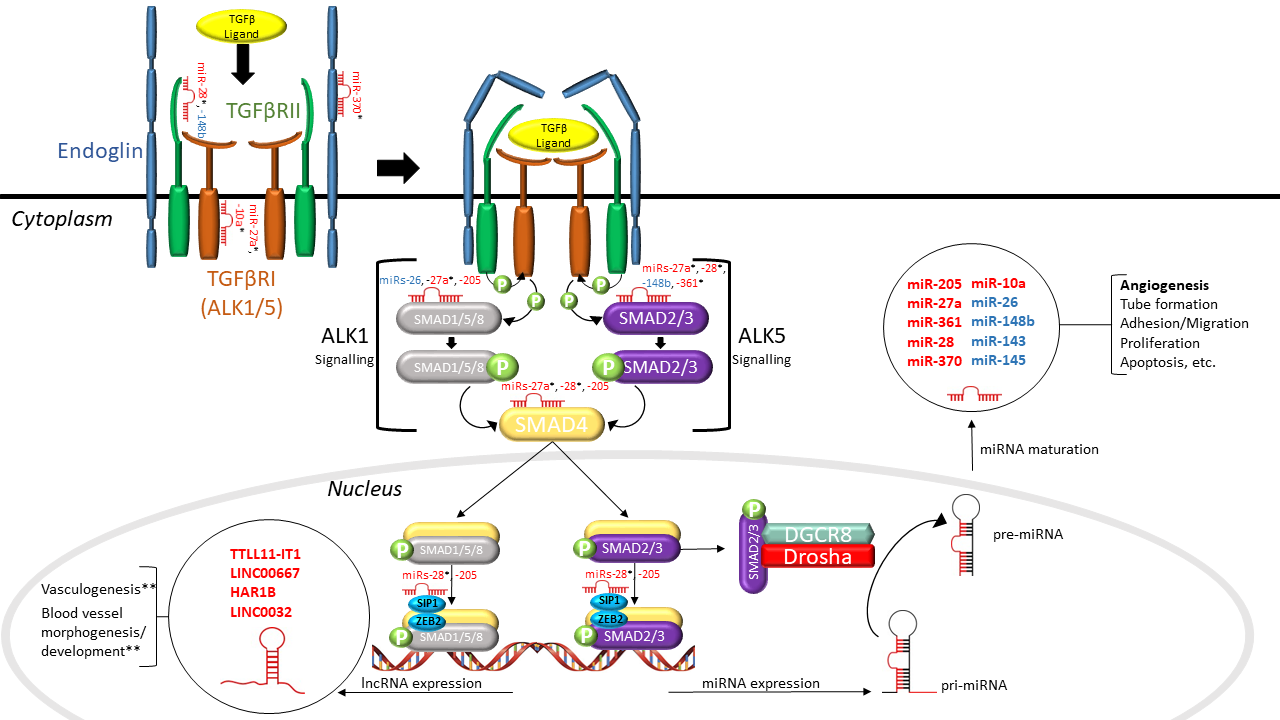

LncRNAs are non-coding RNA species that are greater than 200 nucleotides in length and regulate gene expression post-transcriptionally [18]. LncRNAs can be divided into two functional groups based on their sub-cellular localization: (1) nuclear and (2) cytoplasmic. Nuclear lncRNAs can influence gene expression via various mechanisms, including chromatin remodeling, protein sequestration and the enhancement or dampening of promoter activity [58]. One of the ways that cytoplasmic lncRNAs can influence gene expression is by regulating the availability and stability of miRs by acting as miR “sponges” [58]. Although lncRNA mechanisms have been well characterized, evidence suggests that most lncRNAs are non-functional [58]. Nonetheless, a few lncRNAs have been implicated in vascular and endothelial cell biology. For example, the lncRNA MALAT1 was shown to promote EC proliferation and migration under hypoxic conditions [59]. Conversely, MEG3 was demonstrated to inhibit EC proliferation, survival and tube formation [59]. Singh et al. were the first to identify differential expression of lncRNAs in TGFβ1-stimulated HUVECs [60]. They demonstrated that 2051 and 2393 lncRNAs were significantly upregulated and downregulated, respectively. Of these, MALAT1 was upregulated the most (∼220-fold), contributing to its role in EC biology. Given the functional relevance of lncRNAs in EC biology, one would assume that they may play a role in HHT. Indeed, Tørring et al. sought to profile lncRNAs from nasal mucosa telangiectasias of HHT1 and HHT2 patients [61], and identified 42 lncRNAs that were significantly dysregulated (p < 0.001), including TTLL11-IT1, LINC00667, HAR1B and LINC0032, compared to non-telangiectasial nasal mucosa from the same HHT patients. However, none of the dysregulated lncRNAs have been characterized. Bioinformatic analysis revealed that these lncRNAs were enriched in HHT-related pathways, including vasculogenesis and blood vessel morphogenesis and development (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Interactions between non-coding RNAs and the TGFβ signaling pathway in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT). As shown in this schematic diagram, dysregulated microRNAs (miRs) (in red) identified in HHT patients directly target a number of TGFβ signaling molecules, including SMADs and TGFβRs, and dysregulated lncRNAs (in red) found in HHT patients have a purported role in regulating vasculogenesis and vessel morphogenesis and development. SMAD2/3 can alternatively incorporate with the microprocessor complex to regulate the processing of pri-miRNA to pre-miRNA. Aberrant TGFβ signaling has been found to result in the altered expression of various miRs (in blue) that are involved in angiogenesis. The interaction between non-coding RNAs and TGFβ signaling establishes a narrative for their involvement in HHT pathogenesis. TGFβ: transforming growth factor beta; TGFβRI/II: TGFβ receptor I/II; ALK1/5: activin receptor-like kinase 1/5; miRNA: microRNA; lncRNA: long non-coding RNA; SMAD1/2/3/4/5/8: mothers against decapentaplegic homolog 1/2/3/4/5/8; SIP1: Smad interacting protein 1; ZEB2: zinc finger e-box binding homeobox 2; DGCR8: DiGeorge syndrome critical region gene 8; pri-miRNA: primary miRNA; pre-miRNA: precursor miRNA; “P”: phosphoryl group (* putative targets, ** predicted by bioinformatics).

References

- Zarrabeitia, R.; Albiñana, V.; Salcedo, M.; Señaris-Gonzalez, B.; Fernandez-Forcelledo, J.-L.; Botella, L.-M. A review on clinical management and pharmacological therapy on hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT). Curr. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2010, 8, 473–481. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, J.; Bayrak-Toydemir, P.; Pyeritz, R.E. Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia: An overview of diagnosis, management, and pathogenesis. Genet. Med. 2011, 13, 607–616. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayrak-Toydemir, P.; Mao, R.; Lewin, S.; McDonald, J. Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia: An overview of diagnosis and management in the molecular era for clinicians. Genet. Med. 2004, 6, 175–191. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puente, R.Z.; Bueno, J.; Salcedo, M. Epidemiology of Hereditary Haemorrhagic Telangiectasia (HHT) in Spain. Hered. Genet. 2016, 05, 173. [CrossRef]

- Clark, M.; Berry, P.; Martin, S.; Harris, N.; Sprecher, D.; Olitsky, S.; Hoag, J.B. Nosebleeds in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia: Development of a patient-completed daily eDiary. Laryngoscope Investig. Otolaryngol. 2018, 3, 439–445. [CrossRef]

- McAllister, K.A.; Grogg, K.M.; Johnson, D.W.; Gallione, C.J.; Baldwin, M.A.; Jackson, C.E.; Helmbold, E.A.; Markel, D.S.; McKinnon, W.C.; Murrell, J. Endoglin, a TGF-beta binding protein of endothelial cells, is the gene for hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia type 1. Nat. Genet. 1994, 8, 345–351. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.W.; Berg, J.N.; Baldwin, M.A.; Gallione, C.J.; Marondel, I.; Yoon, S.J.; Stenzel, T.T.; Speer, M.; Pericak-Vance, M.A.; Diamond, A.; et al. Mutations in the Activin Receptor-Like Kinase 1 Gene in Hereditary Haemorrhagic

- Gallione, C.J.; Repetto, G.M.; Legius, E.; Rustgi, A.K.; Schelley, S.L.; Tejpar, S.; Mitchell, G.; Drouin, É.; Westermann, C.J.J.; Marchuk, D.A. A Combined Syndrome of Juvenile Polyposis and Hereditary Haemorrhagic Telangiectasia Associated with Mutations in MADH4 (SMAD4). Lancet 2004, 363, 852–859. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-L, A.; Sanz-Rodriguez, F.; Blanco, F.J.; Bernabéu, C.; Botella, L.M. Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia, a vascular dysplasia affecting the TGF-beta signaling pathway. Clin. Med. Res. 2006, 4, 66–78. [CrossRef]

- Tual-Chalot, S.; Oh, S.P.; Arthur, H.M. Mouse models of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia: Recent advances and future challenges. Front. Genet. 2015, 6, 1–25. [CrossRef]

- Crist, A.M.; Lee, A.R.; Patel, N.R.; Westhoff, D.E.; Meadows, S.M. Vascular deficiency of Smad4 causes arteriovenous malformations: A mouse model of Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia. Angiogenesis 2018, 21, 363–380. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabbà, C.; Pasculli, G.; Lenato, G.M.; Suppressa, P.; Lastella, P.; Memeo, M.; Dicuonzo, F.; Guanti, G. Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia: Clinical features in ENG and ALK1 mutation carriers. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2007, 5, 1149–1157. [CrossRef]

- Bernabéu, C.; Blanco, F.J.; Langa, C.; Garrido-Martin, E.M.; Botella, L.M. Involvement of the TGF-β superfamily signalling pathway in hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia. J. Appl. Biomed. 2010, 8, 169–177. [CrossRef]

- Gallione, C.J.; Richards, J.A.; Letteboer, T.G.W.; Rushlow, D.; Prigoda, N.L.; Leedom, T.P.; Ganguly, A.; Castells, A.; Ploos van Amstel, J.K.; Westermann, C.J.J.; et al. SMAD4 mutations found in unselected HHT patients. J. Med. Genet. 2006, 43, 793–797. [CrossRef]

- Cole, S.G.; Begbie, M.E.;Wallace, G.M.F.; Shovlin, C.L. Anew locus for hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT3) maps to chromosome 5. J. Med. Genet. 2005, 42, 577–582. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayrak-Toydemir, P.; McDonald, J.; Akarsu, N.; Toydemir, R.M.; Calderon, F.; Tuncali, T.; Tang, W.; Miller, F.; Mao, R. A fourth locus for hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia maps to chromosome 7. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2006, 140A, 2155–2162. [CrossRef]

- Albiñana, V.; Zafra, M.P.; Colau, J.; Zarrabeitia, R.; Recio-Poveda, L.; Olavarrieta, L.; Pérez-Pérez, J.; Botella, L.M. Mutation affecting the proximal promoter of Endoglin as the origin of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia type 1. BMC Med. Genet. 2017, 18, 20. [CrossRef]

- Kapranov, P.; Cheng, J.; Dike, S.; Nix, D.A.; Duttagupta, R.; Willingham, A.T.; Stadler, P.F.; Hertel, J.; Hackermuller, J.; Hofacker, I.L.; et al. RNA Maps Reveal New RNA Classes and a Possible Function for Pervasive Transcription. Science 2007, 316, 1484–1488. [CrossRef]

- De Rie, D.; Abugessaisa, I.; Alam, T.; Arner, E.; Arner, P.; Ashoor, H.; Åström, G.; Babina, M.; Bertin, N.; Burroughs, A.M.; et al. An integrated expression atlas of miRNAs and their promoters in human and mouse. Nat. Biotechnol. 2017, 35, 872–878. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.K.; Kim, V.N. Processing of intronic microRNAs. EMBO J. 2007, 26, 775–783. [CrossRef]

- Tanzer, A.; Stadler, P.F. Molecular evolution of a microRNA cluster. J. Mol. Biol. 2004, 339, 327–335. [CrossRef]

- Ha, M.; Kim, V.N. Regulation of microRNA biogenesis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014, 15, 509–524. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denli, A.M.; Tops, B.B.J.; Plasterk, R.H.A.; Ketting, R.F.; Hannon, G.J. Processing of primary microRNAs by the Microprocessor complex. Nature 2004, 432, 231–235. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Kolb, F.A.; Jaskiewicz, L.; Westhof, E.; Filipowicz, W. Single processing center models for human Dicer and bacterial RNase III. Cell 2004, 118, 57–68. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khvorova, A.; Reynolds, A.; Jayasena, S.D. Erratum: Functional siRNAs and miRNAs Exhibit Strand Bias (Cell 115 (209-216)). Cell 2003, 115, 209–216. [CrossRef]

- Jo, M.H.; Shin, S.; Jung, S.R.; Kim, E.; Song, J.J.; Hohng, S. Human Argonaute 2 Has Diverse Reaction Pathways on Target RNAs. Mol. Cell 2015, 59, 117–124. [CrossRef]

- Ipsaro, J.J.; Joshua-Tor, L. From guide to target: Molecular insights into eukaryotic RNA-interference machinery. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2015, 22, 20–28. [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Lucas, A.S.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Y. Identifying microRNA targets in different gene regions. BMC Bioinformatics 2014, 15, S4. [CrossRef]

- Jonas, S.; Izaurralde, E. Towards a molecular understanding of microRNA-mediated gene silencing. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2015, 16, 421–433. [CrossRef]

- Hammond, S.M. An overview of microRNAs. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2015, 87, 3–14. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Ba, Y.; Ma, L.; Cai, X.; Yin, Y.; Wang, K.; Guo, J.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, J.; Guo, X.; et al. Characterization of microRNAs in serum: A novel class of biomarkers for diagnosis of cancer and other diseases. Cell Res. 2008, 18, 997–1006. [CrossRef]

- Hunter, M.P.; Ismail, N.; Zhang, X.; Aguda, B.D.; Lee, E.J.; Yu, L.; Xiao, T.; Schafer, J.; Lee, M.-L.T.; Schmittgen, T.D.; et al. Correction: Detection of microRNA Expression in Human Peripheral Blood Microvesicles. PLoS ONE 2010, 5. [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, P.S.; Parkin, R.K.; Kroh, E.M.; Fritz, B.R.; Wyman, S.K.; Pogosova-Agadjanyan, E.L.; Peterson, A.; Noteboom, J.; O’Briant, K.C.; Allen, A.; et al. Circulating microRNAs as stable blood-based markers for cancer detection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 10513–10518. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chim, S.S.C.; Shing, T.K.F.; Hung, E.C.W.; Leung, T.Y.; Lau, T.K.; Chiu, R.W.K.; Lo, Y.M.D. Detection and characterization of placental microRNAs in maternal plasma. Clin. Chem. 2008, 54, 482–490. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maqbool, R.; Hussain, M.U. MicroRNAs and human diseases: Diagnostic and therapeutic potential. Cell Tissue Res. 2014, 358, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Sohel, M.M.H. Circulating microRNAs as biomarkers in cancer diagnosis. Life Sci. 2020, 248, 117473. [CrossRef]

- Khoury, S.; Tran, N. Circulating microRNAs: Potential biomarkers for common malignancies. Biomark. Med. 2015, 9, 131–151. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Chen, J.; Sen, S. MicroRNA as Biomarkers and Diagnostics. J. Cell. Physiol. 2016, 231, 25–30. [CrossRef]

- Arroyo, J.D.; Chevillet, J.R.; Kroh, E.M.; Ruf, I.K.; Pritchard, C.C.; Gibson, D.F.; Mitchell, P.S.; Bennett, C.F.; Pogosova-Agadjanyan, E.L.; Stirewalt, D.L.; et al. Argonaute2 complexes carry a population of circulating microRNAs independent of vesicles in human plasma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 5003–5008. [CrossRef]

- Vickers, K. C.; Palmisano, B.T.; Shoucri, B.M.; Shamburek, R.D.; Remaley, A.T. MicroRNAs are transported in plasma and delivered to recipient cells by high-density lipoproteins. Nat. Cell Biol. 2011, 13, 423–435. [CrossRef]

- Ismail, N.; Wang, Y.; Dakhlallah, D.; Moldovan, L.; Agarwal, K.; Batte, K.; Shah, P.; Wisler, J.; Eubank, T.D.; Tridandapani, S.; et al. Macrophage microvesicles induce macrophage differentiation and miR-223 transfer. Blood 2013, 121, 984–995. [CrossRef]

- Glinge, C.; Clauss, S.; Boddum, K.; Jabbari, R.; Jabbari, J.; Risgaard, B.; Tomsits, P.; Hildebrand, B.; Kääb, S.; Wakili, R.; et al. Stability of Circulating Blood-Based MicroRNAs – Pre-Analytic Methodological Considerations. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0167969. [CrossRef]

- Moldovan, L.; Batte, K.E.; Trgovcich, J.; Wisler, J.; Marsh, C.B.; Piper, M. Methodological challenges in utilizing miRNAs as circulating biomarkers. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2014, 18, 371–390. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oerlemans, M.I.F.J.; Mosterd, A.; Dekker, M.S.; de Vrey, E.A.; van Mil, A.; Pasterkamp, G.; Doevendans, P.A.; Hoes, A.W.; Sluijter, J.P.G. Early assessment of acute coronary syndromes in the emergency department: The potential diagnostic value of circulating microRNAs. EMBO Mol. Med. 2012, 4, 1176–1185. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shovlin, C.L.; Guttmacher, A.E.; Buscarini, E.; Faughnan, M.E.; Hyland, R.H.; Westermann, C.J.J.; Kjeldsen, A.D.; Plauchu, H. Diagnostic criteria for hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (Rendu-Osler-Weber syndrome). Am. J. Med. Genet. 2000, 91, 66–67. [CrossRef]

- Latino, G.A.; Brown, D.; Glazier, R.H.; Weyman, J.T.; Faughnan, M.E. Targeting under-diagnosis in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia: A model approach for rare diseases? Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2014, 9, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Lupa, M.D.; Wise, S.K. Comprehensive management of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Curr. Opin. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2016, 25, 64–68. [CrossRef]

- Dupuis-Girod, S.; Bailly, S.; Plauchu, H. Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia: From Molecular Biology to Patient Care. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2010, 8, 1447–1456. [CrossRef]

- Hanneman, K.; Faughnan, M.E.; Prabhudesai, V. Cumulative radiation dose in patients with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia and pulmonary arteriovenous malformations. Can. Assoc. Radiol. J. 2014, 65, 135–140. [CrossRef]

- Bushati, N.; Cohen, S.M. microRNA Functions. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2007, 23, 175–205. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ardekani, A.M.; Naeini, M.M. The Role of MicroRNAs in Human Diseases. Avicenna J. Med. Biotechnol. 2010, 2, 161–179. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ha, T.-Y. MicroRNAs in Human Diseases: FromCancer to Cardiovascular Disease. Immune Netw. 2011, 11, 135. [CrossRef]

- Ors-Kumoglu, G.; Gulce-Iz, S.; Biray-Avci, C. Therapeutic microRNAs in human cancer. Cytotechnology 2019, 71, 411–425. [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Zhang, W.; Yu, C.; Ren, J.; An, Z. MicroRNA let-7: Regulation, single nucleotide polymorphism, and therapy in lung cancer. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 2015, 11, C1–C6.

- Castro, D.; Moreira, M.; Gouveia, A.M.; Pozza, D.H.; De Mello, R.A. MicroRNAs in lung cancer. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 81679–81685. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salinas-Vera, Y.M.; Marchat, L.A.; Gallardo-Rincón, D.; Ruiz-García, E.; Astudillo-De la Vega, H.; Echavarría-Zepeda, R.; López-Camarillo, C. AngiomiRs: MicroRNAs driving angiogenesis in cancer (Review). Int. J. Mol. Med. 2019, 43, 657–670. [CrossRef]

- Butz, H.; Rácz, K.; Hunyady, L.; Patócs, A. Crosstalk between TGF-B signaling and the microRNA machinery. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2012, 33, 382–393. [CrossRef]

- Tsagakis, I.; Douka, K.; Birds, I.; Aspden, J.L. Long non-coding RNAs in development and disease: Conservation to mechanisms. J. Pathol. 2020, 250, 480–495. [CrossRef]

- Jaé, N.; Dimmeler, S. Noncoding RNAs in Vascular Diseases. Circ. Res. 2020, 126, 1127–1145. [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.K.; Matkar, P.N.; Quan, A.; Mantella, L.-E.; Teoh, H.; Al-Omran, M.; Verma, S. Investigation of TGF β 1-Induced Long Noncoding RNAs in Endothelial Cells. Int. J. Vasc. Med. 2016, 2016, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Tørring, P.M.; Larsen, M.J.; Kjeldsen, A.D.; Ousager, L.B.; Tan, Q.; Brusgaard, K. Long non-coding RNA expression profiles in hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, 90272. [CrossRef] [PubMed]