Serine/arginine-rich (SR) proteins are important splicing factors in plant development and abiotic/hormone-related stresses. However, evidence that SR proteins contribute to the process in woody plants has been lacking. Using phylogenetics, gene synteny, transgenic experiments, and RNA-seq analysis, we identified 24 PtSR genes and explored their evolution, expression, and function in Popolus trichocarpa. The PtSR genes were divided into six subfamilies, generated by at least two events of genome triplication and duplication. Notably, they were constitutively expressed in roots, stems, and leaves, demonstrating their fundamental role in P. trichocarpa. Additionally, most PtSR genes (~83%) responded to at least one stress (cold, drought, salt, SA, MeJA, or ABA), and, especially, cold stress induced a dramatic perturbation in the expression and/or alternative splicing (AS) of 18 PtSR genes (~75%). Evidentially, the overexpression of PtSCL30 in Arabidopsis decreased freezing tolerance, which probably resulted from AS changes of the genes (e.g., ICE2 and COR15A) critical for cold tolerance. Moreover, the transgenic plants were salt-hypersensitive at the germination stage. These indicate that PtSCL30 may act as a negative regulator under cold and salt stress. Altogether, this study sheds light on the evolution, expression, and AS of PtSR genes, and the functional mechanisms of PtSCL30 in woody plants.

1. Introduction

Alternative splicing (AS) is an important mechanism in the regulation of gene expression in eukaryotes, which enhances transcriptome and proteome diversity

[1][2][1,2]. Over 95% of human protein-coding genes can be alternatively spliced to produce multiple transcripts, such as

KCNMA1 can produce more than 500 mRNA isoforms

[3][4][3,4]. In plants, about 83% and 73% of intron-containing genes undergo AS in

Arabidopsis thaliana and

Oryza sativa, respectively

[5][6][5,6]. There are mainly five different types of AS events, including exon-skipping (ES), intron retention (IR), mutually exclusive exons (MXE), alternative 5′ splice site (A5SS) and 3′ splice site selection (A3SS)

[7]. IR is a major mode of AS in plants, whereas ES is a predominant mode in animals

[8][9][10][8,9,10]. The importance of AS has been clearly manifested by the genetic hereditary diseases caused by splicing defects

[11][12][11,12].

Due to a sessile life form, plants need unique adaptive developmental and physiological strategies to cope with environmental perturbations. AS is emerging as an important process affecting plant development and tolerance to biotic and abiotic stresses. AS can regulate transcriptome and proteome plasticity to respond rapidly to environmental stresses by adjusting the abundance of the functional transcripts of the stress-related genes, such as protein kinases, transcription factors, splicing regulators, and pathogen-resistance genes

[13]. For example, hundreds of genes, such as novel cold-responsive transcription factors and splicing factor/RNA-binding proteins, showed rapid AS changes in response to cold (called ‘early AS’ genes)

[14]. More than 6,000 genes were reported to undergo changes of AS patterns under salt stress

[15][16][15,16]. In addition, AS is also involved in a range of other functions, such as photosynthesis, circadian clock, flowering time, and metabolism

[17][18][19][20][17,18,19,20].

Pre-mRNA splicing processing is catalyzed by a spliceosome, a large flexible RNA-protein complex consisting of five small nuclear ribonucleoprotein particles (snRNPs) and numerous types of non-snRNP proteins

[21][22][21,22]. Serine/arginine-rich (SR) proteins, the major regulators in the splicing of pre-mRNAs, are evolutionarily conserved splicing factors

[23][24][23,24]. In plants, SR proteins were defined as one or two N-terminal RNA recognition motifs (RRMs) followed by a downstream RS domain of at least 50 amino acids with over 20% SR or RS dipeptide

[25]. SR family proteins have been identified in many plant species, such as green algae, moss, and various flowering plants. The number of

SR genes varies among different species; for example, there are 18 members in

Arabidopsis, 22 in

O. sativa, 21 in

Dimocarpus longan Lour, 40 in

Triticum aestivum, and 18 in

Brachypodium distachyon [26][27][28][29][26,27,28,29]. Plant SR proteins can be classified into six subfamilies, including SR, SC, RSZ, RS, SCL, and RS2Z. The SR, SC, and RSZ subfamilies have orthologs in mammals, while the RS, SCL, and RS2Z subfamilies are unique to plants with novel structural features

[25]. RS subgroup members have two RRM domains, and the second RRM domain lacks the SWQDLKD signature, which is a characteristic of SR-subfamily proteins. RS2Z subfamily members have two Zn-knuckles and one RS domain, followed by an SP-rich region. SCL-subfamily members have a single RRM domain followed by an RS domain, and possess a short N-terminal extension that contains multiple RS and SP dipeptides

[30][31][30,31].

Plant

SR genes are involved in various plant growth and development processes. The overexpression of

AtSRp30 resulted in a delayed transition from the nutrition to reproductive periods, prolonged life cycle, and increased individual size

[32]. The loss of

Arabidopsis SC35/SCL proteins led to multiple effects on plant morphology and development, such as serrated leaves and later flowering

[33]. Additionally, plant

SR genes can be alternatively spliced, and their splicing patterns are affected by various developmental and environmental signals. For example, the overexpression of

RSZ36 and

SRp33b can change the splicing patterns of

RSZ36 and

SRp32 in rice, respectively

[34]. High temperatures may increase the expression of the active isoforms of

SR30 but reduce the active isoform of

SR34 in

Arabidopsis [35]. Moreover,

SR genes may allow functional redundancy in the processes of plant growth and development. In

Arabidopsis, the

sc35-scl quintuple mutant (

scl28 scl30 scl30a scl33 sc35) exhibited the obvious phenotypes of serrated rosette leaves and late-flowering, while no obvious morphological alterations were observed in the double or triple mutants

[33].

2. Identification of PtSR Family Genes and Their Characteristics

Firstly, we searched for the homologs of

Arabidopsis SR proteins in

P. trichocarpa genome by the BLASTP program

[36][37]. Taking account of the definition of the RS domain, which has at least 50 amino acids sharing over 20% RS content by consecutive RS or SR dipeptides in plants

[25], we screened the homologs to obtain a total of 24 PtSR proteins. We then assessed the basic characteristics of the 24 PtSR proteins; for example, their molecular weights (

MWs) ranged from 20.46 to 34.56 kDa, with an average value of 29.3 kDa (

Table S1). Of note, all the proteins had an extremely high isoelectric point (pI) between 9.9 and 11.6, and, consequently, were highly cationic at neutral or acid pH. This is supported by the fact that SR proteins can bind the negatively charged RNA in nuclei

[37][38]. Additionally, based on the grand average of hydropathy (GRAVY) values, all the proteins were predicted to be hydrophilic between −1.772 and −0.881, supporting the soluble nature of PtSR proteins. Detailed characteristics of the assessed

PtSR-family genes are presented in

Table S1.

3. Phylogenetic and Architectural Analysis of PtSR Family Genes

Since

SR genes have been widely studied in

Arabidopsis, we selected

SR genes from

Arabidopsis as a reference and constructed a phylogenetic tree based on the full-length alignment of the SR proteins in the species

Arabidopsis and

P. trichocarpa (

Figure 1A). PtSR proteins were classified into the six known subfamilies, SR, SC, RSZ, RS, SCL, and RS2Z. This result agreed well with those from

Arabidopsis [38][39], indicating that the

SR gene family was highly conserved, at least in the dicots. As compared to animals, ~50% of

PtSR genes were plant-specifically evolved

SR genes, including the previously reported RS, SCL, and RS2Z subfamilies

[25].

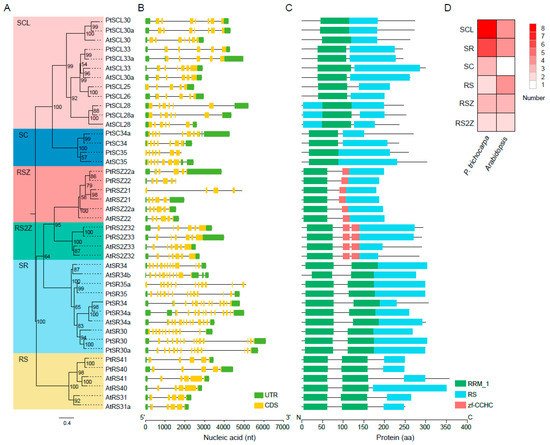

Figure 1. Phylogenetic relationships and exon/intron and domain architectures of SR-family genes in P. trichocarpa and Arabidopsis. Phylogenetics of SR genes. Multiple alignment of the Arabidopsis and P. trichocarpa SR proteins were performed by MAFFT to construct a maximum likelihood (ML) tree by IQ-TREE. (A) The ML tree was assessed by an ultrafast bootstrap with 5000 replicates, and bootstrap values greater than 50% are shown. The six clusters in shaded colors indicate the known conserved subfamilies (i.e., SCL, SC, RSZ, RS2Z, SR, and RS); (B) exon/intron structures of PtSR genes. UTR and CDS indicate the untranslated region and coding sequences, respectively; (C) protein domains of PtSR genes. The visualizations of exon/intron and protein-domain architectures were created by TBtools, using their gene- and protein-information datasets; (D) a heatmap showing the numbers of the six subfamilies of Arabidopsis and P. trichocarpa SR genes.

Gene exon/intron structure diversity is one of the possible mechanisms for explaining the evolution of multiple gene families, to which end, we further analyzed the structures of the

PtSR genes (

Figure 1B). Observably, the

PtSR genes were interrupted by multiple introns, ranging between 4 and 13, and, expectedly, the clustered

PtSR genes showed similar exon–intron structures and shared a recent common ancestor. In detail, the same subfamily had a very similar number of introns (

Figure 1B). For example, the

SR-subfamily genes had the most introns, ranging between 12 and 13, while the

RS2Z-subfamily genes had the same number (six) of introns. This showed that the subfamilies of the

SR-family genes were highly conserved after their divergence from their nearby subfamilies.

In the case of PtSR-protein domains, we retrieved the conserved protein domains based on the annotated domains from the Pfam database

[39][40]. Two types of homolog-based domains were finally identified, including the RRM and zf-CCHC domains (

Figure 1C). Expectedly, all the PtSR proteins had at least one RRM and RS domain. Meanwhile, some differences were also found between the subfamilies, such as the one and two zf-CCHC domains, respectively, in the RSZ and RS2Z subfamilies. Finally, and noteworthy, among the six subfamilies in

P. trichocarpa, SCL was the largest, followed by SR; whereas, in

Arabidopsis, three subfamilies, SCL, SR, and RS, were very close in number (

Figure 1D). Next, we mapped the detailed expansion of these subfamilies.

4. The Expansion History of the PtSR Gene Family in P. trichocarpa

To investigate the evolution of

PtSR gene family, we determined their chromosomal distributions and gene-duplication types. The

PtSR genes were distributed unequally to

P. trichocarpa chromosomes (the outer circle in

Figure 2A). Three

PtSR genes (

PtRSZ22,

PtSCL25 and

PtRS2Z32) were located on chromosome (Chr) 6, followed by two

PtSR genes on Chrs 2, 5, 8, 10, 14 and 16, respectively. Of note, except for the SCL-subfamily genes (e.g.,

PtSCL28 and

PtSCL30) being located in the same chromosomes, genes from the same

PtSR subfamily were mainly distributed to different chromosomes, declining the possibility of generating

PtSR genes by tandem or proximal duplications.

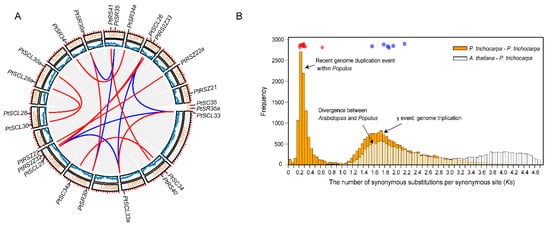

Figure 2. Chromosomal distribution and expansion events of

PtSR gene family. (

A) The chromosomal distribution and collinearity gene blocks the containing

PtSR genes. The outer circle indicates

P. trichocarpa’s 19 chromosomes (Chr) and scaffolds (s), marked with a distribution of

PtSR genes; the middle circle indicates gene density on the corresponding chromosomes; and the inner grey curves indicate gene collinearity blocks between and within chromosomes, where the close paralogous pairs of

PtSR genes are marked in blue or red curves, according to their expansion events; (

B) the frequency of

Ks values of the collinearity of gene pairs within the

P. trichocarpa genome and between the

P. trichocarpa and

Arabidopsis genomes. The blue circles indicate the

PtSR gene pairs generated by genome triplication event (i.e., γ) before the divergence of

P. trichocarpa and

Arabidopsis, and the red circles indicate the

PtSR gene pairs generated by the recent genome duplication of

P. trichocarpa after the divergence from

Arabidopsis. The collinearity of the

PtSR gene pairs and their

Ks values are provided in

Table S2.

To determinate molecular mechanisms generating the

PtSR-family genes, we traced their expansion history and found a total of 16 collinear gene blocks, including 21

PtSR genes (the inner color lines in

Figure 2A). This finding showed that the whole- and/or segmental-genome duplication pattern was the dominant molecular mechanism generating the

PtSR genes. To date the events of the 16 collinearity gene blocks, we calculated the synonymous substitution rate (Ks) of the duplicated gene pairs (

Table S2) and found the blocks could be mainly classified into two categories (

Figure 2B). The first category included six gene pairs (shown in blue lines and dots in

Figure 2A,B), and their Ks values varied between 1.5649 and 2.1702 (

Figure 2B,

Table S2), which were around the whole-genome triplication event (i.e., γ) in the recent common ancestor of

P. trichocarpa and

Arabidopsis [40][41]. The other category included ten gene pairs (shown in red lines and dots in

Figure 2A,B), and their Ks values varied between 0.2164 and 0.6339 (

Figure 2B,

Table S2), and were concentrated around the most recent whole-genome duplication event of

P. trichocarpa [41][42]. This recent duplication event was successful in replicating the genes of the SCL and SR subfamilies (

Figure 2), explaining well the existing larger number of the two subfamilies in

P. trichocarpa than in

Arabidopsis (

Figure 1D). Together, the two categories demonstrated at least two expansion stages of the

SR gene family through genome polyploidization, which provided the dominant molecular mechanism producing the existing

PtSR genes in

P. trichocarpa.

5. GO Term Enrichment and Promoter Cis-element Analysis of PtSR Genes

We performed GO term-enrichment analysis of

PtSR genes to investigate the molecular functions and biological processes that

PtSR genes might participate in. The result showed that

PtSR genes could participate in various biological processes, such as spliceosome assembly, RNA splicing, mRNA export, the regulation of metabolic processes, the response to stress, and the regulation of gene expression (

Figure 3A). This indicated that

PtSR genes not only act as splicing factors for RNA-splicing and metabolism processes at the post-transcriptional level, but also might be involved in the diverse and complicated regulation of gene expression at the transcriptional level.

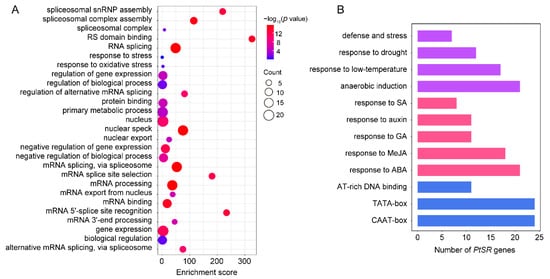

Figure 3. GO term enrichment and promoter cis-element analysis of PtSR genes. (A) GO term enrichments of PtSR genes. The dot sizes represent the numbers of enriched genes and the colored bars represent the significant levels of GO term enrichment; (B) the numbers of PtSR genes containing various cis-acting elements. Purple, red, and blue bars represent the cis-acting elements in response to abiotic stresses, phytohormones, and the fundamental core elements in PtSR gene promoters, respectively.

To identify the

cis-acting elements in the promoters of

PtSR genes, we analyzed the 2-kb sequences upstream of the translation-start sites of

PtSR genes in PlantCARE

[42][43] (

Figure 3B). Firstly, there were well-known housekeeping

cis-acting elements in the promoters of all the

PtSR genes, such as TATA-box and CAAT-box. Also, some

cis-acting elements were enriched in response to phytohormones, such as abscisic acid (ABA), methyl jasmonate (MeJA), salicylic acid (SA), and gibberellin (GA). Furthermore, the

cis-acting elements were also enriched in response to abiotic stresses, such as low-temperature, drought, defense and stress, and anaerobic induction (

Figure 3B,

Table S3). The housekeeping and hormone/abiotic-responded

cis-elements, together, demonstrated that

PtSR genes are probably expressed in constitutive regulation, but also in response to hormone/abiotic stresses, and we next studied their expressions in

P. trichocarpa tissues and under hormone/abiotic stresses.

6. Constitutive and Abundant Expression Patterns of PtSR Genes in P. trichocarpa

To investigate the expression profiles of

PtSR genes, we analyzed the expression levels of

PtSR genes by RNA-seq data in

P. trichocarpa tissues including roots, stems, and leaves. According to RNA-seq data, we found that

PtSR genes mainly exhibited constitutive expression profiles in all of the three tissues (

Figure 4A), and the relative expression levels of

PtSR genes were significantly higher than the background-expressed genes (

Figure 4B). Of note, many

SR genes showed an observably higher expression than the well-known housekeeping gene (

Figure 4A). The results together suggested that

PtSRs were constitutively and abundantly expressed in different tissues of

P. trichocarpa.

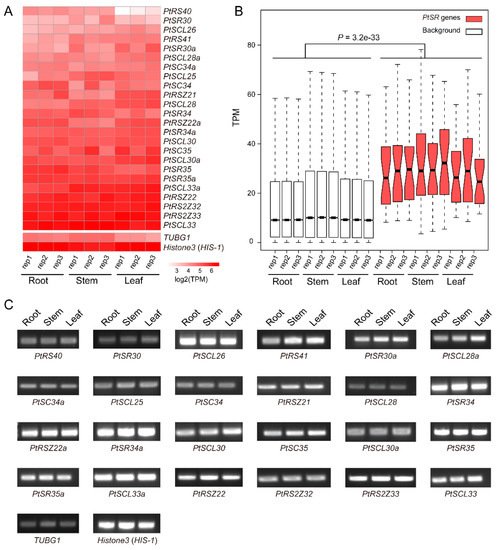

Figure 4. The expression profiles of PtSR genes in P. trichocarpa tissues. (A) A heatmap of the expression profiles of PtSR family genes in roots, stems, and leaves. Transcripts per million reads (TPM) was used to represent the expression of each gene and log2 transformed to generate the heatmap; (B) A boxplot showing expression differences between PtSR genes and background genes. Except for PtSR genes, the other genomic expressed genes were selected as background, and the differential level in expression between PtSR genes and the background was assessed by Wilcoxon test.