Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Rayya Al Balushi and Version 3 by Conner Chen.

Metalla-ynes and poly(metalla-ynes) have emerged as unique molecular scaffolds with fascinating structural features and intriguing photo-luminescence (PL) properties. Their rigid-rod conducting backbone with tunable photo-physical properties has generated immense research interests for the design and development of application-oriented functional materials.

- metalla-ynes

- poly(metalla-ynes)

1. Main-Chain Systems

Transition metal complexes display a multitude of colorful optical (absorption/emission) and interesting magnetic properties due to the presence of metal ions in different oxidation states [1][38]. Moreover, multi-dimensional applications of transition metal complexes are well established [2][39]. It is well demonstrated that when one or more transition metal ions (decorated with suitable auxiliary ligands) are embedded in an organic framework via σ-linkage, new conducting materials are realized with limitless features and properties. Such materials, commonly known as metalla-ynes or poly(metalla-ynes), were studied and reviewed by several groups [3][40]. Both homo- and heterometallic σ-acetylide metal complexes with one or more types of transition metal ions are known in the literature, with a majority on homometallic systems [4][5][1,2]. The combination of two transition metals provides an effective way to realize new materials with unique structural features and improved properties such as high solubility and transparency [6][41]. Although heterometallic poly-ynes containing Ni/Pt and Pd/Pt have been known for a long time [7][8][42,43], focus on using other metals has been sparse, possibly due to the challenging synthesis of suitable monomers and/or polymers. In this sub-section, we exemplify the structure and properties of heterometallic molecular systems while clusters [9][44] are beyond the scope of this paper. Attempts were made to include recent references that have not been covered before [10][25].

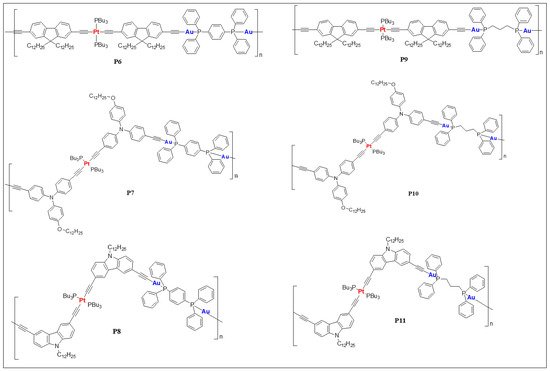

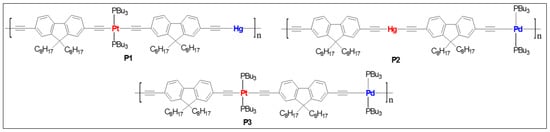

Dixneuf and co-workers [11][45] reported the first one dimensional Ru(II)/Pd(II) mixed metalla-yne as a yellow oligomer in good yield (84%) and moderate chain length (Mw = 14,800, Mn = 7800). Basic structural characterization showed the formation of mixed metalla-yne but no photo-physical properties were reported. Wong and co-workers [12][46] reported the very first example of soluble rigid-rod heteronuclear Pt(II)/Hg(II) poly(metalla-yne) (P1, Figure 12) and their corresponding model complexes. The reported white polymer exhibits excellent thermal stability (Td = 366 ± 5 °C), and polydispersity (Mw = 29,790, Mn = 15,704, Table 1). The fluorescence quantum yield of the heterobimetallic polymer (Φf = 0.52 in DCM, Table 1) was found to be lower than the homometallic trans polymers (Φf = 2.53 for Hg(II) and 0.62 for Pt(II) in DCM) but higher than the cis counterpart (Φf = 0.1 in DCM). Similarly, the heterometallic Pt(II)/Hg(II) complex showed a weak triplet emission at room temperature (RT) and a slightly stronger optical power limiting (OPL) performance than the homo-nuclear Hg(II) complexes. The transparency window of the poly-ynes in the visible regime coupled with their OPL performance was achieved by interrupting π- conjugation via copolymerization with Hg and tuning the Pt geometry (cis and trans).

Figure 12. Heterometallic poly(metalla-ynes) P1–P3.

Table 1. Photoluminescence (PL) data of some selected heterometallic poly(metalla-ynes) P1–P3 and P6–P11.

| Code | Metals | Molecular Weight (×104) | λabs (nm) |

λems (nm) |

Lifetime of S1 (τa, ns) |

Lifetime of T1 (τb, µs) |

Φ (%) |

Eg (eV) | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mw | Mn | |||||||||

| P1 | Pt/Hg | 2.9 | 1.5 | 386 | 409 a, 542 b,582 b | 1.23 | 194.38, 202.84 | 0.52 | 3.01 | [12][46] |

| P2 | Pd/Hg | 0.45 | 0.40 | 411 | 430 a, 544 b, 578 b | 0.92 | 12.19, 22.71 | 12.60 | 2.85 | [13][47] |

| P3 | Pt/Pd | 2.5 | 1.3 | 415 | 437 a, 540 b, 588 b | 0.89 | 193.7, 188.2 | 0.60 | 2.83 | [13][47] |

| P6 | Pt/Au | - | 2.4 | 270, 276, 305, 319, 345, 362, 387 | 417 a, 438a, 450a, 539 a, 548 b, 587 b, 625 b, 642 b | 0.71 | 181.63 | 1.03 | 2.98 | [14][22] |

| P7 | Pt/Au | - | 2.7 | 264, 276, 316sh, 377 | 504a, 504 b, 545 b, 563 b | 10370 | 130.80 | 0.62 | 3.00 | [14][22] |

| P8 | Pt/Au | - | 2.9 | 253, 262, 276sh, 317, 335 | 405 a, 425 a, 455 a, 495 a, 534 a, 456 b, 492 b, 507 b, 527 b | 0.99 | 44.31 | 0.27 | 3.19 | [14][22] |

| P9 | Pt/Au | - | 2.1 | 275, 305, 319, 344, 361, 384 | 412 a, 432 a, 449sh a, 542 a, 584 a, 548 b, 586 b, 619 b | 0.63 | 137.84 | 1.66 | 3.00 | [14][22] |

| P10 | Pt/Au | - | 2.4 | 268, 275, 314sh, 373 | 504 a, 503 b, 529 b, 603 b | 6460 | 165.23 | 1.69 | 3.01 | [14][22] |

| P11 | Pt/Au | - | 3.1 | 253, 261, 316, 334 | 402 a, 421 a, 438 a, 455 a, 503 a, 457 b, 493 b, 507 b | 0.72 | 40.14 | 0.30 | 3.12 | [14][22] |

Mw: average weight molecular weight, Mn: number weight molecular weight, λabs: absorption wavelength peaks, λems: emission wavelength peaks, sh: shoulder, a: measured at 298 K, b: measured at 77 K, Φ: quantum yield, Eg: energy gap.

A comparative study on homo- and heterometallic poly-ynes (P1–P3, Figure 12) indicated that Hg(II) and Pt(II) containing poly-ynes are better candidates for OPL than the corresponding Pd(II) poly-ynes as the former display absorption maxima below 400 nm [13][47]. It was shown that the heterometallic complex P1 shows better transparency (maximum absorption wavelength (λmax) = 386 nm, Table 1) than that of homometallic Pt(II) complexes (Figure 23). Theoretical calculations suggested that in heterometallic complexes, the contribution of dπ orbitals to the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) was more from Pd/Pt than the Hg. Conversely, the contribution of pπ orbitals to the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) was more from the Hg fragment, in line with the earlier studies [12][46].

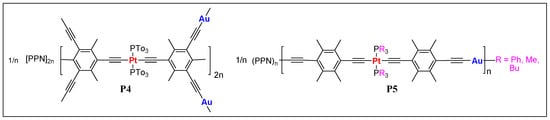

In 2005, Vicente et al. [15][48] reported the very first examples of Pt(II)/Au(I) heterometallic anionic poly(metalla-ynes) P4 and P5 (Figure 34). The polymers, obtained by reacting Pt(II) bis- or tetra acetylides with PPN[Au(acac)2] (PPN = bis(triphenylphosphine)iminium cation, acac = acetylacetone) were poorly characterized due to the extremely low solubility. The only polymer P5 (R = Bu) was soluble and could be characterized by nuclear magnetic resonance (1H, 13C, and 31P NMR) and gel permission chromatography (GPC) techniques, which showed comparatively good chain length of the polymers (up to 667 units).

Figure 34. Pt(II)/Au(I) heterometallic anionic poly(metalla-ynes) P4 and P5. (PPN = bis(triphenylphosphine)iminium cation).

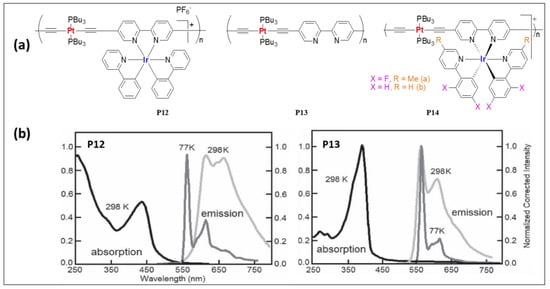

Wong and co-workers [14][22] reported heterometallic Au(I)–Pt(II) poly(metalla-ynes) (P6–P11, Figure 45), in which the impact of merging two different metals can be clearly observed (Table 1). Compared to the homometallic systems, Au(I)–Pt(II) poly(metalla-ynes) showed blue-shifted absorption maxima and cut-off absorption wavelengths in solution slightly shifted with respect to monomeric Pt(II) complexes. Merging two different metallic cores also significantly improved the transparency of the resulting material, which was attributed to the weak metal-ligand interactions and conjugation interruption by auxiliary ligands.

2. Side-Chain Systems

2.1.

d-d

Metal-Containing Systems

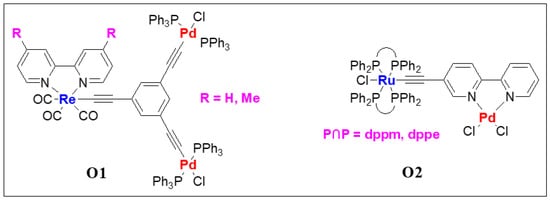

Compared to the main chain heterometallic systems, dimers and polymers with second organometallic fragments attached via chelating ligand are more common in the literature. Several oligo- and poly(metalla-ynes) bearing heterometallic fragments were synthesized and studied in the past. In this section, we discuss some pertinent examples of both small and large molecular systems with two or more types of metal ions. As observed in the earlier examples, the inclusion of a second metal affects the PL properties. Among d-d combinations, the use of Ir(III) and Re(I) with Pt(II) metalla-ynes is very common as the mixed-metal systems show improved photo-physical behavior [16][49]. It is well established that the photo-physical properties of a material are the function of the molecular structure of the main-chain and pendant ligands. Studies on heterometallic branched complexes indicated that the absorption and emission energies shift to the red upon the incorporation of the Pd(II) fragment moiety [17][50]. Compared to monometallic Re(I) complexes (maximum absorption wavelength (λabsmax) = 408–418 nm), trimetallic complexes O1 (R = H or Me, Figure 56) exhibit low energy transition at λabsmax = 416–426 nm in solution (Table 2). Similarly, in tetrahydrofuran (THF) solution at RT, Re(I) complexes showed maximum emission wavelength (λemmax) at 625–636 nm (lifetime, τ0 = < 0.1 μs), while Pd(II)/Re(I) complexes emitted at λemmax = 628–639 nm (τ0 = < 0.1 μs, Table 2). Heterometallic complex O2 (Figure 56) bearing Pd(II)/Ru(II) core exhibits highly red shifted absorption band (Table 2) compared to monometallic Ru(II)-counterpart [18][51].

Figure 56. Re(I)/Pd(II) hetero-trimetallic (O1) and Ru(II)/Pd(II) heterometallic (O2) complexes.

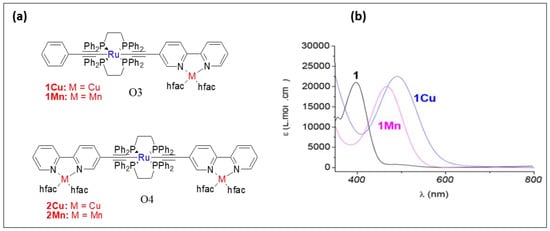

Piazza and coworkers [19][52] assessed the photo-physical and magnetic properties of Ru(II)/Cu(I) and Ru(II)/Mn(I) couples O3 and O4 (Figure 67). Interestingly, a long-distance magnetic coupling between the terminal Cu(II) units through Ru(II) fragment was noted. Moreover, heterometallic systems displayed low energy bands in the visible region (Table 2). Cu(II) complexes exhibit higher thermal stability compared to Mn(I) complexes.

Figure 67. (a) Structures of bimetallic and trimetallic Ru/Cu and Ru/Mn complexes O3 and O4 and (b) the optical absorption spectra (in CH2Cl2) of O3 when M = Cu (1Cu) and Mn (1Mn) along with the corresponding monometallic Ru-bipyridyl compound (1). Reprinted (adapted) with permission from Di Piazza, E.; Boilleau, C.; Vacher, A.; Merahi, K.; Norel, L.; Costuas, K.; Roisnel, T.; Choua, S.; Turek, P.; Rigaut, S., Ruthenium carbon-rich group as a redox-switchable metal coupling unit in linear trinuclear complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 56, (23), 14540–14555. Copyright 2017 American Chemical Society.

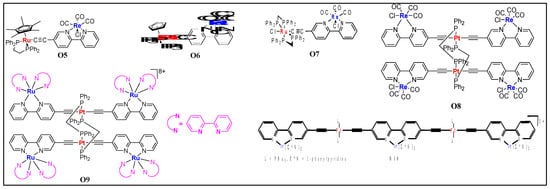

In contrary to this, theoretical and experimental studies suggest that the two metal centers in binuclear heterometallic Ru(I)/Re(I) complexes O5–O7 (Figure 78) are weakly coupled [20][27]. Chen et al. [21][26] found that the insertion of one or more heterometal (Re/Ru) reduces the π* energy level in the ethynyl bipyridyl ligand in platinaynes and thus alters the photo-physical properties. For example, complexes (O8 and O9, Figure 78) showed a red-shift in optical absorption and longer lifetime (in µs) compared to monometallic platinaynes (Table 2). Complex with Pt/Ru couple (λabsmax = 504 nm, λemmax = 658 nm and τ0 = < 0.1 μs) showed red shifted absorption and emission compared to Pt/Re λabmax= 427 nm, λemmax = 595 nm and τ0 = < 1.5, 0.22 μs) and Pt (λabmax= 392 nm, λemmax = 540 nm and τ0 = < 0.1 μs) complexes.

Figure 78. Structures of the d-d and d-f type heterometallic complexes O5−O10.

In addition to these small molecular systems, several polymeric complexes bearing d-d metal fragments were also investigated [22][53]. Complex O10 (Figure 8) is an example of a highly emissive (Table 2) pentanuclear complex containing Pt(II) and Ir(III) fragments [23][54]. An efficient triplet energy transfer between the terminal and central Ir(III) cores through the Pt(II) moiety was reported in such systems.

Table 2. Photoluminescence (PL) data of some selected heterometallic metalla-ynes O1−O4 and O8−O10.

| Code | Metals | λabs(nm) | λems(nm) | Lifetime of S1(τa, µs) | Lifetime of T1(τb, µs) | Φ (%) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O1 (R = Me) | Pd/Re | 236, 284, 336sh, 416 | 628 a, 589 b | ˂0.1 | 0.73 | - | [17][50] |

| O1 (R = H) | Pd/Re | 238, 284, 334sh, 426 | 639 a, 594 b | ˂0.1 | 0.62 | - | [17][50] |

| O2 (dppm) | Pd/Ru | 386 | - | - | - | - | [18][51] |

| O2 (dppe) | Pd/Ru | 389 | - | - | - | - | [18][51] |

| O3 | Ru/Cu | 308, 494 | - | - | - | - | [19][52] |

| O3 | Ru/Mn | 308, 468 | - | - | - | - | [19][52] |

| O4 | Ru/Cu | 308, 494 | - | - | - | - | [19][52] |

| O4 | Ru/Mn | 306, 468 | - | - | - | - | [19][52] |

| O8 | Pt/Re | 271, 382, 427 | 595 | 1.5, 0.22 | - | 0.0018 | [21][26] |

| O9 | Pt/Ru | 243, 291, 360, 504 | 658 | <0.1 | - | 0.045 | [21][26] |

| O10 | Pt/Ir | 255, 315, 415, 435 | 560 a, 613 a, 663 a,550 b, 595 b, 651 b | 2.3 | 2.5, 1.9 | 3.3 | [23][54] |

λabs: absorbtion wavlength peaks, λems: emission wavelength peaks, sh: shoulder, a: measured at 298 K, b: measured at 77 K, Φ: quantum yield.

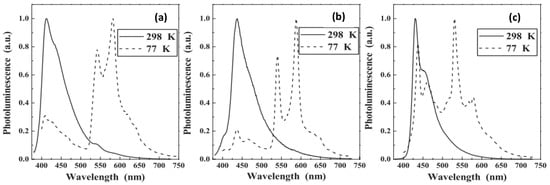

Harvey and coworkers [24][55] prepared a series of mono- and bimetallic Pt(II)/Ir(III) complexes (P12–P14, Figure 89a) and assessed their photo-physical properties. The photophysical features of the heterometallic complexes were found to be a hybrid of the monometallic complexes used. For instance, Ir(III)-containing 5,5′-bisacetylide complex (Φ = 1.6%, τ = 0.09 μs) showed structureless emission maxima at 638 nm while Pt(II) dimer (Φ = 13.7%, τ = 39.2 μs) showed a blue-shifted structured emission at 561 nm. The introduction of a second luminescent fragment in Pt(II) complex (Φ = 13.7%, τ = 39.2 μs) led to Pt/Ir (Φ = 4%, τ = 1.33 μs) dimer with red-shifted emission at 623 nm. Under similar conditions, polymer P13, which is a Bipy containing Pt(II) poly-yne exhibits emission at 561 nm (Φ = 12.8%, τ = 9.2 μs, Table 3). Ir-containing polymer P12 showed emission at 617 nm (Φ = 2.6%, τ = 1.22 μs, Table 3) (Figure 89b). Later the same group [25][56] compared the photo-physical and electrochemical properties of complex P14 (Figure 89a). Upon fluorination of the pendant ligand, the nature of the excited state remains the same; however, there were some changes in the absorption and in emission profiles (Table 3).