Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Lindsay Dong and Version 3 by Lindsay Dong.

Cashew nut shell liquid (CNSL), a natural oil and a byproduct of cashew nut food processing, with a high content of phenolic lipids. The rational modification of their structures has emerged as a successful medicinal chemistry approach to the development of novel anti-AD lead candidates. The biological profile of the newly developed CNSL derivatives towards validated AD targets will be discussed together with the role of these molecular targets in the context of AD pathogenesis.

- Alzheimer’s disease

- natural products

- cashew nut shell liquid

- anacardic acid

- cardanol

- cardol

1. Introduction

Dementia is a major public health concern, amplified by a fast-growing older population. Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common cause of dementia, accounting for about 75% of cases; other causes include cerebrovascular diseases and mixed pathologies [1].

The development of a cure is a key priority of AD research but is not an easy task. Although medications have existed for more than twenty-five years, they are classified as symptomatic, i.e., can only temporarily reduce the symptoms of cognitive impairment and marginally slow disease progression (and only in selected patients). In June 2021, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the disease-modifying antibody aducanumab, despite ongoing concerns about its efficacy [2]. All controversy aside, the fact that it is the first new drug approved for AD since 2003, demonstrates that the development of new, effective drugs suffers an unsustainably high failure rate [3]. Referred to as the “valley of death”, more than 200 drug candidates had previously failed in late-stage clinical trials, with a success rate of 0.4%, as compared with 20% for cancer [4]. While statistics paint a pretty grim picture, thanks to the immense efforts devoted by the scientific community, as for 2020 there were 121 agents in clinical development Phases 1–3 trials, of which 80% putatively targets disease modification [5]. However, their translational potential is difficult to predict.

As long as a cure remains elusive, AD stands as a dramatic unmet clinical need and a most challenging and pressing therapeutic area, so as scientists, we should do everything possible to solve the problem, and pursue any drug discovery approach founded on solid hypotheses [6].

One of such approach is the use of natural products. Historically, natural products from the fungi, plant and animal kingdoms have been the source of virtually all the drugs introduced into the market. Morphine, isolated from opium in 1806 or digoxin, isolated from Digitalis lanata in 1869 are exemplary cases [7]. Still today, natural products continue to enter the clinic or to provide valuable chemical scaffolds inspiring novel drug discovery. This particularly applies to the CNS domain. Intriguingly, a recent analysis has indicated that ~84% of approved drugs for CNS diseases are natural product or natural product-inspired molecules, including drugs for AD [8].

Further, Stasiuk et al. [30] tested the effects of the same phenolic lipids on AChE from Electrophorus electricus (Ee) and confirmed that those from A. occidentale (14a, 15a, 16c, and 17c) were the most active, inhibiting the enzyme activity at micromolar level. The resorcinolic lipids from rye bran (16a, 18, and 19) showed moderate AChE inhibition, which increased with the number of carbon atoms of the alkyl chain. Merulinic acid (20) was less effective (Table 2). The authors also estimated the degree of inhibition by measuring the variation of the intrinsic fluorescence of Trp residues from AChE, which correlates with AChE conformational changes induced by the tested compound.

Further, Stasiuk et al. [30] tested the effects of the same phenolic lipids on AChE from Electrophorus electricus (Ee) and confirmed that those from A. occidentale (14a, 15a, 16c, and 17c) were the most active, inhibiting the enzyme activity at micromolar level. The resorcinolic lipids from rye bran (16a, 18, and 19) showed moderate AChE inhibition, which increased with the number of carbon atoms of the alkyl chain. Merulinic acid (20) was less effective (Table 2). The authors also estimated the degree of inhibition by measuring the variation of the intrinsic fluorescence of Trp residues from AChE, which correlates with AChE conformational changes induced by the tested compound.

2. Cashew Nut Shell Liquid (CNSL) Components for the Discovery of Anti-AD Lead Candidates

2.1. CNSL Phenolic Lipids: The Raw Material

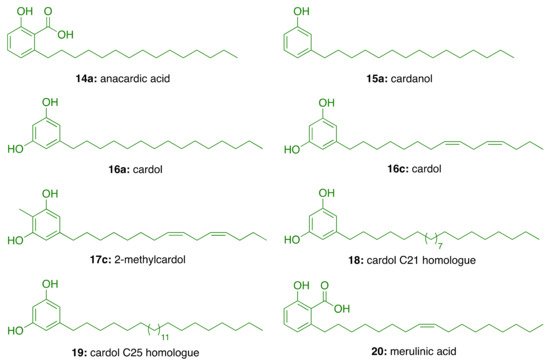

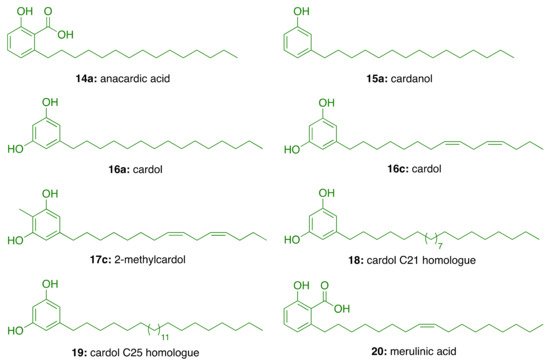

Natural CNSL, produced in the spongy mesocarp of the cashew nut (Anacardium occidentale L.), is a viscous and acrid oil comprising 25–30% of the fruit’s weight in natura. It is one of the richest sources of non-isoprenoid phenolic lipids, i.e., anacardic acids (14, 71–82%), cardanols (15, 2–9%), cardols (16, 13–20%) and 2-methylcardols (17, 1–4%) (Figure 4) [9]. In turn, the technical CNSL—obtained by thermomechanical process at temperatures of 185–195 °C—presents the mixture of cardanols as a major component (15, 67–95%)—due to the decarboxylation of anacardic acids—followed by the mixture of cardols (16, 3–19%), 2-methylcardols (17, 1–4%), anacardic acids (14, 1–2%), minority components (3–4%), and polymeric material (1–21%) (Figure 4). In general, the relative composition of each component (saturated and unsaturated) in the natural CNSL phenolic lipid mixtures shows saturated derivatives (15:0) in a smaller proportion, while triene derivatives (15:3) are found in a higher percentage (Table 1). Table 1. Relative percentage composition of unsaturated phenolic constituents of natural CNSL, quantified by GC/MS.| Components | Percentage (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anacardic Acids | Cardanols | Cardols | 2-Methylcardols | |

| Saturated (15:0) | 2.2–3.0 | 3.9–4.4 | 0.2–2.7 | 0.9–1.3 |

| Monoene (15:1) | 25.0–33.3 | 21.6–32.2 | 8.4–15.2 | 16.3–25.3 |

| Diene (15:2) | 17.8–32.1 | 15.4–18.2 | 24.2–28.9 | 20.6–24.4 |

| Triene (15:3) | 36.3–50.4 | 45.1–59.0 | 36.5–67.2 | 49.8–62.2 |

Adapted from reference [9].

CNSL is produced on a large scale by cold press extraction, solvent extraction [10][11], thermomechanical process, and supercritical CO2 extraction [12]. From a chemical point of view, the CNSL phenolic lipid mixtures are an excellent raw material for a series of chemical transformations that exploit their aromatic rings, polar functional groups, and the double bonds in the side chains. These have been used for the manufacture of insecticides, germicides, antioxidants, thermal insulators, friction material, plasticizers, surfactants, paints, and varnishes [9]. Despite the huge applicability of CNSL, its usage is limited to sectors with low added-value and, due to the lack of investment in technology aimed at its full exploitation, the majority of CNSL derivatives are exported at negligible prices with an average price of USD 250/ton [9].

From a medicinal chemistry perspective, the molecular scaffolds of the CNSL phenolic lipids constitute natural biophores with electronic and hydrophobic characteristics relevant to molecular recognition by different therapeutic targets. These natural compounds have privileged structures capable of mimicking fatty acids and act as signaling molecules that regulate various physiological effects on metabolism and inflammation [13]. In this context, CNSL phenolic lipids—purified or as mixtures—and synthetic derivatives thereof show biological activities [14], as antibacterial [15][16][17], antioxidant [18], enzyme inhibitors [19][20][21][22], antiproliferative [23][24][25][26], and antiviral agents [27]. It is worth highlighting the relevance of studies in lipidomics in the development of novel drugs for diseases such as cancer, diabetes, infectious disease, and also AD [28].

2.2. Phenolic Lipids as AChE Inhibitors

In the search for AChE inhibitors of plant origin, Stasiuk et al. [29] evaluated in isolated sheep erythrocyte membranes the AChE inhibitory activity of phenolic lipids isolated from A. occidentale (anacardic acid (14a), cardanol (15a), cardol (16c), and 2-methylcardol (17c), and three resorcinolic lipids from rye grain (C15:0 (16a), C21:0 (18), and C25:0 (19, Figure 1). Of the compounds isolated from rye grain only the homologues C21:0 (18) and C25:0 (19) showed inhibitory effect with IC50 values of 44.5 μM and 38.5 μM, respectively. In turn, those isolated from A. occidentale, i.e., cardol (16c) and anacardic acid (14a), inhibited AChE activity at lower micromolar concentrations (IC50 = 15.5 µM and IC50 = 22 μM, respectively). In contrast, 2-methylcardol (17c) and cardanol (15a) did not show any inhibitory effect [29].

Figure 1. Phenolic lipids from A. occidentale, rye grain, and M. tremellosus.

Table 2. AChE inhibition of phenolic lipids from A. occidentale, rye grain, and M. tremellosus.

| Compound | IC50 (μM) |

|---|---|

| Anacardic acid (14a) | 3.0 ± 0.2 |

| Cardanol (15a) | 4.0 ± 0.2 |

| Cardol (16a) | >94 |

| Cardol (16c) | 3.5 ± 0.2 |

| 2-Methycardol (17c) | 5.0 ± 0.4 |

| Cardol C21 homologue (18) | 44 ± 0.5 |

| Cardol C25 homologue (19) | 44 ± 4.2 |

| Merulinic acid (20) | >94 |

Adapted from reference [30].

2.3. CNSL-Derived AChE Inhibitors

Trp residues at the anionic sites of the CAS (Trp84) and PAS (Trp286) of human AChE are relevant for the molecular recognition of different ligands [31][32]. Bearing in mind the charge transfer interaction between the positive pole of the quaternary nitrogen of ACh with these aromatic residues, we envisaged more potent AChE inhibitors by the insertion of protonatable amino groups in the structures of CNSL-derived lipids.2.3.1. CNSL-Derived Rivastigmine Analogues

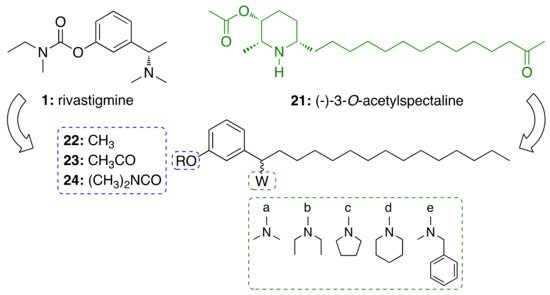

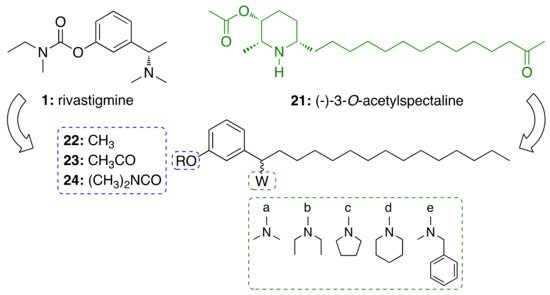

For this endeavor, we were inspired by the structures of rivastigmine (1) and the alkaloid (−)-3-O-acetylspectaline (21), obtained in large quantities from flowers and green fruits of Senna spectabilis. Given the structural similarities between 21 and saturated cardanol (15a), this latter has been selected as a suitable starting point to develop CNSL-derived rivastigmine analogues [33][34]. Paula et al. [33][34] designed new potential AChE inhibitors by means of theoretical calculations. Particularly, the target compounds were modeled following a molecular hybridization strategy between 1 and cardanols (15a). To explore structure-activity relationships, the phenolic hydroxyl of 15a was replaced by methoxy (22), acetyl (23), and N,N-dimethylcarbamoyl groups (24). As for secondary amines, alicyclic and heterocyclic amines (N,N-dimethylamine (a), N,N-diethylamine (b), pyrrolidine (c), and piperidine (d)) were selected to study the conformational flexibility of this subunit. The aromatic N-methylbenzylamine (e) was also considered for evaluating whether an additional Π-Π interaction with the Trp84 or Phe330 residues could be established (Figure 2). The calculations of the electronic structures of the fifteen designed derivatives were initially performed at RHF level using 6-31G, 6-31G(d), 6-31+G(d) and 6-311G(d,p) base functions, then B3LYP level with the 6-31G, 6-31G (d) and 6-311+G(2d, p). Among the proposed compounds, the structures featuring the N,N-dimethycarbamoyl, N,N-dimethylamine and pyrrolidine groups showed a better correlation with 1. Based on the descriptors E (HOMO-1), E (LUMO+1), C–O56, C–NR2, E(LUMO), and ΔL+1, obtained in the principal component analysis (PCA), the N,N-dimethylcarbamates 24a–e emerged to be the most promising anticholinesterase candidates. To validate the theoretical study, the compounds were synthesized as racemic mixtures and evaluated against EeAChE. Compounds 24a–c inhibited AChE in a concentration-dependent manner, whereas 24d and 24e showed negligible activity, by inhibiting the enzyme by less than 25% at 100 μM. As predicted by theoretical studies, the N,N-dimethylamino derivative 24a turned out to be the most potent inhibitor (IC50 = 50 μM) of the series, followed by the pyrrolidinyl derivative 24c (IC50 = 84 μM), and the diethylamino 24b (IC50 = 251 μM) [27].

Figure 2. Design of cardanol-derived AChE inhibitors by hybridization between rivastigmine (1) and (−)-3-O-acetylspectaline (21).

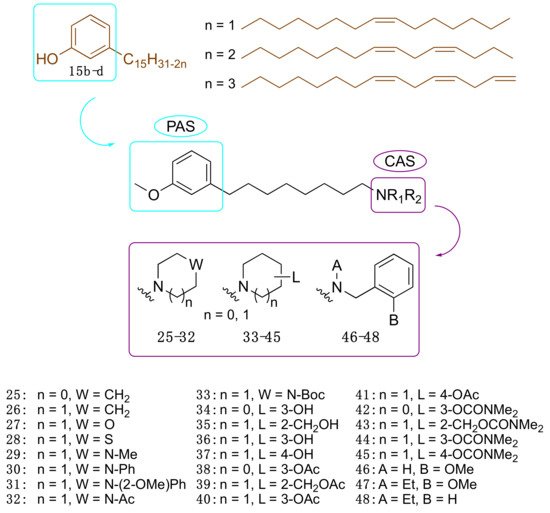

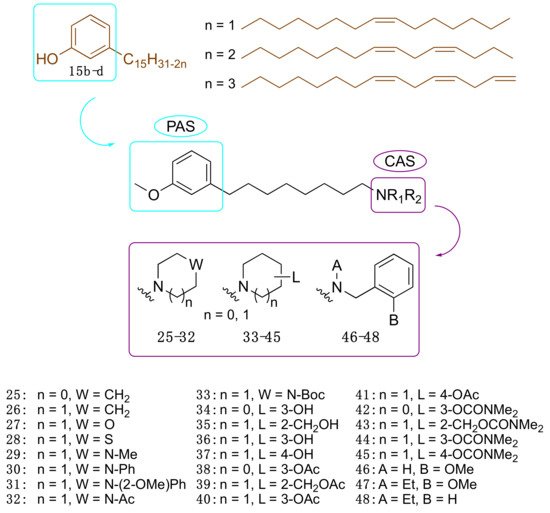

Collectively, twenty-four compounds were synthesized from the mixture of cardanols 15b–d and evaluated in terms of EeAChE inhibition profile at 100 µM. Of these, nineteen compounds inhibited the enzyme by more than 50%.

We report in Table 3 the best performing derivatives, with IC50 values below 20 µM. Additionally, most of the derivatives did not show appreciable toxicity against HT-29 cells, up to a concentration of 100 μM, which indicates a potential drug-like behaviour [35].

Collectively, twenty-four compounds were synthesized from the mixture of cardanols 15b–d and evaluated in terms of EeAChE inhibition profile at 100 µM. Of these, nineteen compounds inhibited the enzyme by more than 50%.

We report in Table 3 the best performing derivatives, with IC50 values below 20 µM. Additionally, most of the derivatives did not show appreciable toxicity against HT-29 cells, up to a concentration of 100 μM, which indicates a potential drug-like behaviour [35].

a Data are geometric means from 2–3 independent experiments, each performed in triplicate. b Selectivity index: eqBChE/EeAChE IC50 ratio. c Data are from a global fit to averaged data from 2–3 independent experiments, each performed in triplicate. Data taken from reference [35].

Notably, compound 47, bearing a N-ethyl-N-(2-methoxybenzyl)amine moiety, showed the highest inhibitory activity against EeAChE, with a promising IC50 of 6.6 μM, and a similar inhibition profile against the human isoform (IC50 = 5.7 μM). Furthermore, 47 was predicted to cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB) by a PAMPA-BBB assay [35]. All in all, these data suggested that the approach of obtaining potential anti-AD compounds from CNSL was worth of further pursuit and development.

To understand the different AChE inhibitory profiles of benzylamines 46–48, Silva et al. [42] carried out theoretical studies to identify key physicochemical properties underlying the experimental data. Particularly, electronic calculations of molecular descriptors, which included molecular volume, polarizability, polar surface area, dissociation constant (pKa), and distribution coefficient (LogD), and PCA were performed together with molecular dynamics and molecular docking. It was possible to verify that a modified cardanol (obtained from the replacement of the hydroxyl by a methoxyl group) and the protonated benzylamine derivatives assume characteristics of electron donor and electron acceptor, respectively, as revealed by electronic structure calculations. In fact, the energies of the HOMO boundary orbitals, HOMO-1, LUMO and LUMO+1, are important descriptors for measuring molecular similarities and grouping inhibitors according to their inhibitory profiles, as shown in the PCA results. Interestingly, molecular docking calculations confirmed a dual binding mode within the human AChE cavity, a characteristic that seems crucial for the stability of this type of complex [42]. In particular, it was noted that ligands 47 and 48 are more likely to bind in an inward orientation, mimicking the donepezil X-ray pose [42].

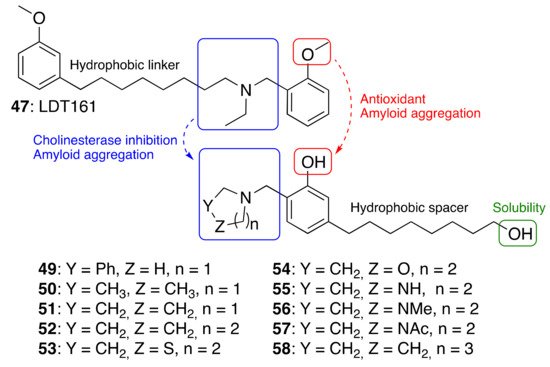

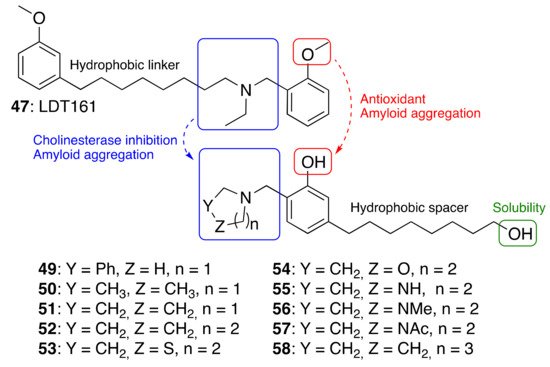

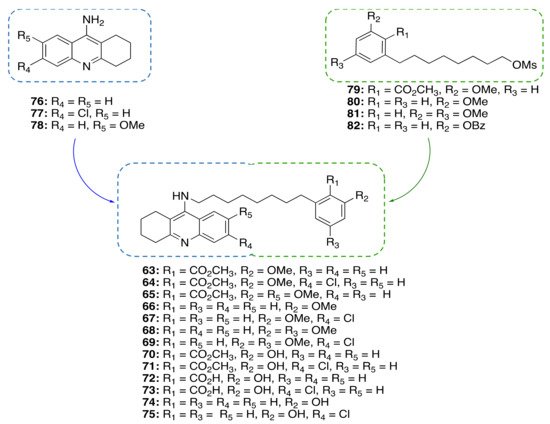

The synthesized compounds 49–58 were tested in vitro for their ability to inhibit human AChE and BChE, using the Ellman assay. Then, their anti-amyloid properties were assesed by transmission electron microscopy and their antioxidant (HORAC) profiles were evaluated in comparison with ferulic acid as reference compound. The antioxidant activity was further confirmed in SHSY-5Y cells. Lastly, the assessment of preliminary drug-like properties—in terms of BBB permeation (PAMPA-BBB assay), toxicity in HepG2 cells, plasma stability and kinetic solubility-, was also performed.

The most interesting results are summarized in Table 4 [43]. As regards to the initial drug-likeness evaluation, they were found potentially BBB permeable, devoid of hepatotoxicity, stable in plasma and soluble. Notably, 52 and 58, which combine cholinesterase activity and anti-amyloid/antioxidant capacity together with good drug-like properties, emerged as the best performing compounds. Thus, we succeeded in identifying phenols 52 and 58 as promising multifunctional cholinesterase inhibitors, modulating amyloid and oxidative cascades.

Table 4. Inhibitory activity against AChE and BChE and antioxidant activity of cardanol derivatives 49–58.

The synthesized compounds 49–58 were tested in vitro for their ability to inhibit human AChE and BChE, using the Ellman assay. Then, their anti-amyloid properties were assesed by transmission electron microscopy and their antioxidant (HORAC) profiles were evaluated in comparison with ferulic acid as reference compound. The antioxidant activity was further confirmed in SHSY-5Y cells. Lastly, the assessment of preliminary drug-like properties—in terms of BBB permeation (PAMPA-BBB assay), toxicity in HepG2 cells, plasma stability and kinetic solubility-, was also performed.

The most interesting results are summarized in Table 4 [43]. As regards to the initial drug-likeness evaluation, they were found potentially BBB permeable, devoid of hepatotoxicity, stable in plasma and soluble. Notably, 52 and 58, which combine cholinesterase activity and anti-amyloid/antioxidant capacity together with good drug-like properties, emerged as the best performing compounds. Thus, we succeeded in identifying phenols 52 and 58 as promising multifunctional cholinesterase inhibitors, modulating amyloid and oxidative cascades.

Table 4. Inhibitory activity against AChE and BChE and antioxidant activity of cardanol derivatives 49–58.

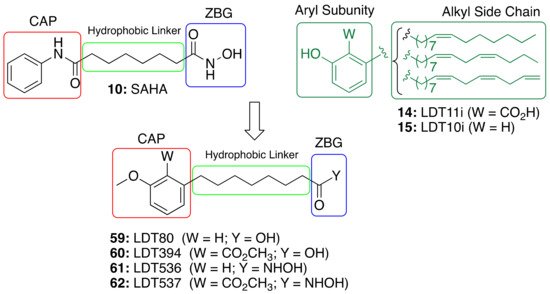

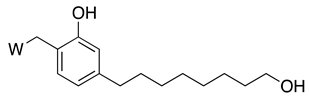

61 and 62 acted mainly on class I and II HDACs, with an inhibition percentage of approximately 80%. As expected, 9 modulated the activity of HDAC1 and 6 with roughly equivalent submicromolar potency. Both 61 and 62 exhibited a similar HDAC inhibitory profile to 9, with inhibitory potencies that were only slightly decreased (by 2.7 to 6.5-fold) (Table 5). Thus, the obtained results supported the starting idea that the insertion of the hydroxamate moiety on a CNSL backbone provides SAHA-like HDAC inhibitors. Indeed, acid 61, devoid of the hydroxamate moiety, showed only a modest inhibition (12%) at 10 µM (Table 4). This was further confirmed by Western blots of acetyl-H3, and total H3 after treatment of N9 cells. Additionally, compounds 61 and 62 were able to cross the BBB by passive diffusion as their Pe values were superior to those of standard AD drugs (tacrine, donepezil, and rivastigmine). Moreover, both compounds, and particularly 62, were able to effectively modulate glial cell-induced inflammation and to revert the M1 pro-inflammatory phenotype.

a IC50 inhibitory concentration (μM) or % inhibition at 20 μM of human recombinant AChE and human serum BChE. IC50 values are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) of at least two experiments each performed in triplicate. b Antioxidant activity is expressed as Gallic Acid Equivalent (GAE). GAE values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) of three experiments (n = 3). ND = not determined; n.a. = not applicable. Data taken from reference [43].

2.3.2. CNSL-Derived Dual Binding AChE Inhibitors

Motivated by the above results, we considered cardanols 15b–d as suitable frameworks for the design of AChE inhibitors with higher potency. To this end, we envisaged that combining two different pharmacophoric units could be a valuable strategy to increase activity. Particularly, we sought to link the cardanol skeleton, which might interact with the PAS through its aromatic end, with a fragment able to fish the CAS, to obtain dual binding AChE inhibitors (Figure 37) [35]. As a CAS key molecular feature, we selected fragments bearing a cationic head, which included a protonatable amino moiety belonging to different systems: heterocyclic amines such as pyrrolidine (25), piperidine (26), morpholine (27), thiomorpholine (28), N-substituted piperazines (29–33), hydroxylated pyrrolidine (34) and piperidines (35–37) and their corresponding O-acetyl (38–41) and O-dimethylcarbamates (42–45). Since the N-ethyl-N-(2-methoxybenzyl)amino moiety has been successfully exploited by us and others to obtain powerful dual binding AChEIs [36][37][38][39][40][41], we also synthesized hybrids 46–48 (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Cardanol-derived AChE inhibitors 25–48.

Table 3. Selectivity and cholinesterase inhibition of selected cardanol-derived compounds.

| Compound | EeAChE IC50(μM) a |

eqBChE IC50 (μM) a |

SI b | EeAChE Ki (μM) c |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | LDT148 | 19.6 | 16.4 | 0.8 | 22.4 (3) |

| 40 | LDT149 | 16.1 | 19.0 | 1.2 | 19.0 (3) |

| 42 | LDT154 | 13.7 | 22.8 | 1.7 | 8.6 (2) |

| 44 | LDT150 | 14.3 | 23.5 | 1.7 | 22.4 (3) |

| 46 | LDT167 | 17.2 | 3.1 | 0.2 | 17.0 (3) |

| 47 | LDT161 | 6.6 | 5.0 | 0.8 | 24.4 (3) |

| 48 | LDT160 | 16.1 | 8.0 | 0.5 | 10.4 (2) |

2.3.3. Cardanol-Derived Cholinesterase Inhibitors with Antioxidant and Anti-Amyloid Properties

As a further step, we were interested in the design of multifunctional CNSL-derived compounds, endowed with additional beneficial properties beyond AChE inhibition. Thus, we rationally manipulated the structure of dual binding AChE inhibitor methoxy–cardanol 47 (LDT161) (Figure 4) [43]. In this novel series, we kept the free phenolic group as in cardanols 15, with the objective of inhibiting Aβ aggregation and preserving the antioxidant properties, commonly found in phenols. Furthermore, we maintained a protonable aminomethyl group, critical for the inhibitory profile against both cholinesterases. Finally, the introduction of a terminal -OH on the C8 aliphatic chain was performed with the aim of enhancing solubility and membrane permeability. This modification might also allow the establishment of an additional H-bond interaction that potentially increases potency towards the target(s). Collectively, the set of cardanol derivatives 49–58 was designed with the goal of obtaining cholinesterase inhibitors with concomitant antioxidant and anti-amyloid properties (Figure 4) [43].

Figure 4. Cardanol-derived multifunctional compounds 49–58.

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compounds | % Inhibition hAChE a |

IC50 hAChE (μM) ± SEM a |

% Inhibition hBChE a |

IC50 hBChE (μM) ± SEM a |

HORAC b |

| Gallic Acid Equivalents |

|||||

| 49 | 19.4 ± 7.1 | ND | 68.3 ± 1.3 | 6.74 ± 0.7 | 3.70 ± 0.05 |

| 50 | 12.4 ± 1.2 | ND | |||

Table 5. In vitro inhibition of HDAC1 and HDAC6 by 60–62 and reference compound (vorinostat).

| Compound | HDAC1 IC50 ± SEM [nM] |

HDAC6 IC50 ± SEM [nM] |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <10 | |||||||

| 9 | Vorinostat | 119 | 53 | ||||

| 60 | LDT394 | 50.5 ±0.7 | 17.5 ± 3.5 | 5.49 ± 0.58 | |||

| 12% * | 12% * | 51 | 31.1 ± 2.8 | ||||

| 61 | 47.6 ± 4.1 | 59.0 ± 0.8 | LDT536 | 316.2 ± 37 | 190.1 ± 38.213.3 ± 0.5 | 4.88 ± 0.05 | |

| 52 | 40.5 ± 1.8 | 30.0 ± 2.6 | 73.5 ± 0.4 | ||||

| 62 | LDT537 | 6.12 ± 0.8 | 4.37 ± 0.54 | ||||

| 774.7 ± 14.4 | 215.4 ± 28.6 | 53 | 12.1 ± 0.8 | ND | 16.6 ± 2.4 | ND | 4.38 ± 0.23 |

| 54 | <5 | ND | <10 | ND | 9.73 ± 0.86 | ||

| 55 | ND | 17.7 ± 3.1 | ND | 1.49 ± 0.20 | |||

| 56 | <5 | ND | 10.6 ± 2.1 | ND | 4.80 ± 0.49 | ||

| 57 | <10 | ND | <5 | ND | 4.52 ± 0.64 | ||

| 58 | <10 | 785 ± 42 | 77.1 ± 0.2 | 4.62 ± 0.14 | 3.50 ± 0,23 | ||

| 47 | 5.65 ± 0.48 | n.a. | |||||

| Ferulic acid | 4.04 ± 0.51 | ||||||

2.4. CNSL-Derived HDAC Inhibitors

The role of saturated anacardic acid 14a as an epigenetic modulator, inhibiting p300 and GCN5 histone acetyltransferases (HAT), is well known [44]. However, 14a was never reported as a HDAC inhibitor. Given the structural similarity between the hydroxamic HDAC inhibitor vorinostat (10, SAHA) and the acids LDT80 (59) and LDT394 (60), we considered them valuable starting points in the search for CNSL-derived HDAC inhibitors [45]. The aromatic rings present in the original mixtures of anacardic acids (14) and cardanols (15) transformed into O-methylated derivatives represent the CAP subunit—a variation aimed at establishing SAR—while the zinc binding group (ZBG) relies on the hydroxamic acid 61 and 62 generated by the interconversion of the carboxylic acid groups 59 and 60. The hydrophobic linker between CAP and ZBG subunits, found in SAHA, is resembled by a C8 aliphatic chain, characteristic of CNSL derivatives after oxidative cleavage (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Design of CNSL-derived HDAC inhibitors LDT536 (61) and LDT537 (62) from the octanoic acids LDT80 (59) and LDT394 (60).

The inhibitory profiles of compounds LDT536 (61) and LDT537 (62) were assessed against human histone deacetylases of class I (HDAC1, HDAC2, HDAC3 and HDAC8), class II (HDAC4, HDAC5, HDAC6, HDAC7, HDAC9 and HDAC10) and class IV (HDAC11) [45]. The obtained results confirmed our rationale, providing CNSL derivatives with a promising HDAC inhibitory profile. Particularly, derivatives

* Inhibition at 10 µM. Reprinted with permission from reference [45], Copyright 2019, American Chemical Society.

2.5. Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Phenolic Lipids from CNSL

As stated above, CNSL phenolic lipids possess strong anti-inflammatory action, which is beneficial for the development of effective anti-AD compounds [44]. Generally, inflammation can be reduced via the inhibition of pro-inflammatory mediators, as well as the increase of the anti-inflammatory mediator production. Recently, the anti-inflammatory potential of anacardic acid 14a was studied on lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced inflammation in RAW264.7 cell line [46]. In particular, 14a at 50 µM effectively decreased the expression of the TNF-α, COX-2, iNOS, NF-κB, IL-1β and IL-6 pro-inflammatory genes. Furthermore, 14a was able also to exert protective effects by reducing nitric oxide (NO) and IL-6 production [46]. Therefore, 14a preventing both the release of pro-inflammatory mediators and downregulating the expression of cytokines emerges as a valuable treatment for preventing inflammation. The in vitro anti-inflammatory profile was further validated by in vivo studies in Swiss albino mice [47]. Results from this study revealed that 14a at 25 mg/kg inhibits carrageenan-induced edema. Moreover, 14a decreased leukocyte and neutrophilic migration, and increased the levels of reduced glutathione. It also showed anti-nociceptive activities, by decreasing licking, abdominal writhing, and latency to thermal stimulation. Collectively, these results suggest that 14a possesses anti-inflammatory and antinociceptive properties and also diminishes oxidative stress in acute experimental models.A Framework Combination Approach towards Rationally Designed CNSL-Derived Multitarget Compounds

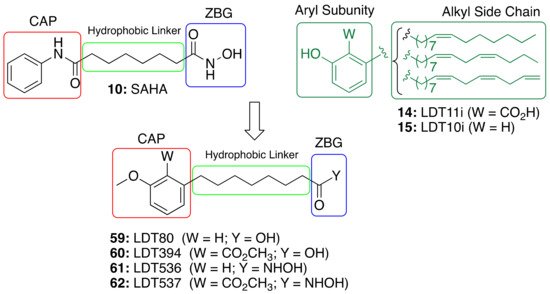

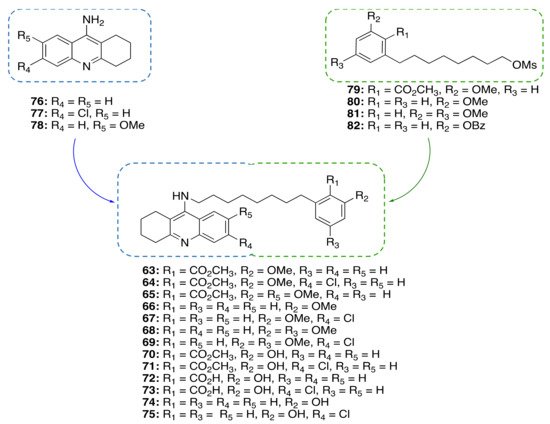

Based on the promising anti-inflammatory activity of 14a, we applied a framework combination strategy to the design and synthesis of a series of CNSL-derived compounds-tacrine hybrids (63–75) for the treatment of AD [48]. We combined in a single chemical entity tacrine moieties (76–78, Figure 6) with a modified CNSL framework (79–82). Considering that the presence of the long alkyl chain (C15) of 14a might limit drug-likeness due to excessive lipophilicity, we turned our attention to the shorter-chain (C8) CNSL derivatives (76–79). In this way, we aimed to create new CNSL-tacrine hybrids which in principle maintained the tacrines’ anticholinesterase activity, combined with the anti-inflammatory activity of CNSL compounds, and possessed drug-like properties. Notably, screening of anticholinesterase activity highlighted potent and selective AChE/BChE inhibitors (63, 64 and 70), with subnanomolar activities. The excellent BChE activity of 63 (IC50 = 0.0352 nM) was rationalized by the solved X-ray crystal structure. Compounds 63 and 64 exerted neuroprotective/neuroinflammatory effects in microglial BV-2 cells treated with LPS. Particularly, 63 and 64 reduce pro-inflammatory mediators, i.e., TNF-α, IL-1β, iNOS, and COX-2. Furthermore, they acted as anti-neuroinflammatory compounds by inhibiting the transcriptional activation of NF-κB, without causing cytotoxicity in microglial, neuronal, and hepatic cell lines. Lastly, their BBB permeability was also confirmed by BBB-PAMPA assay. All in all, the collected data corroborated our rational design for obtaining effective multitarget anti-AD compounds based on CNSL structure.

Figure 6. Design of CNSL-derived tacrine hybrid compounds 63–75.

References

- Livingston, G.; Huntley, J.; Sommerlad, A.; Ames, D.; Ballard, C.; Banerjee, S.; Brayne, C.; Burns, A.; Cohen-Mansfield, J.; Cooper, C. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. Lancet 2020, 396, 413–446.

- Rabinovici, G.D. Controversy and Progress in Alzheimer’s Disease—FDA Approval of Aducanumab. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 771–774.

- Elmaleh, D.R.; Farlow, M.R.; Conti, P.S.; Tompkins, R.G.; Kundakovic, L.; Tanzi, R.E. Developing Effective Alzheimer’s Disease Therapies: Clinical Experience and Future Directions. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2019, 71, 715–732.

- Cummings, J.L.; Morstorf, T.; Zhong, K. Alzheimer’s disease drug-development pipeline: Few candidates, frequent failures. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2014, 6, 37.

- Cummings, J. Drug Development for Psychotropic, Cognitive-Enhancing, and Disease-Modifying Treatments for Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2021, 33, 3–13.

- Bolognesi, M.L. Neurodegenerative drug discovery: Building on the past, looking to the future. Future Med. Chem. 2017, 9, 707–709.

- Calixto, J.B. The role of natural products in modern drug discovery. Acad. Bras. Cienc. 2019, 91 (Suppl. S3), e20190105.

- Bharate, S.S.; Mignani, S.; Vishwakarma, R.A. Why Are the Majority of Active Compounds in the CNS Domain Natural Products? A Critical Analysis. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 10345–10374.

- Mazzetto, S.E.; Lomonaco, D.; Mele, G. Óleo da castanha de caju: Oportunidades e desafios no contexto do desenvolvimento e sustentabilidade industrial. Quim. Nova 2009, 32, 732–741.

- Phani Kumar, P.; Paramashivappa, R.; Vithayathil, P.J.; Subba Rao, P.V.; Srinivasa Rao, A. Process for isolation of cardanol from technical cashew (Anacardium occidentale L.) nut shell liquid. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 4705–4708.

- Tyman, J.H. Synthetic and Natural Phenols; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1996.

- Patel, R.N.; Bandyopadhyay, S.; Ganesh, A. Extraction of cashew (Anacardium occidentale) nut shell liquid using supercritical carbon dioxide. Bioresour. Technol. 2006, 97, 847–853.

- Sung, B.; Pandey, M.K.; Ahn, K.S.; Yi, T.; Chaturvedi, M.M.; Liu, M.; Aggarwal, B.B. Anacardic acid (6-nonadecyl salicylic acid), an inhibitor of histone acetyltransferase, suppresses expression of nuclear factor-kappaB-regulated gene products involved in cell survival, proliferation, invasion, and inflammation through inhibition of the inhibitory subunit of nuclear factor-kappaBalpha kinase, leading to potentiation of apoptosis. Blood 2008, 111, 4880–4891.

- Stasiuk, M.; Kozubek, A. Biological activity of phenolic lipids. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2010, 67, 841–860.

- Green, I.R.; Tocoli, F.E.; Lee, S.H.; Nihei, K.; Kubo, I. Design and evaluation of anacardic acid derivatives as anticavity agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 43, 1315–1320.

- Swamy, B.N.; Suma, T.K.; Rao, G.V.; Reddy, G.C. Synthesis of isonicotinoylhydrazones from anacardic acid and their in vitro activity against Mycobacterium smegmatis. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2007, 42, 420–424.

- Green, I.R.; Tocoli, F.E.; Lee, S.H.; Nihei, K.; Kubo, I. Molecular design of anti-MRSA agents based on the anacardic acid scaffold. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2007, 15, 6236–6241.

- Trevisan, M.T.; Pfundstein, B.; Haubner, R.; Würtele, G.; Spiegelhalder, B.; Bartsch, H.; Owen, R.W. Characterization of alkyl phenols in cashew (Anacardium occidentale) products and assay of their antioxidant capacity. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2006, 44, 188–197.

- Pereira, J.M.; Severino, R.P.; Vieira, P.C.; Fernandes, J.B.; da Silva, M.F.; Zottis, A.; Andricopulo, A.D.; Oliva, G.; Corrêa, A.G. Anacardic acid derivatives as inhibitors of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase from Trypanosoma cruzi. Bioorgan. Med. Chem. 2008, 16, 8889–8895.

- Freitas, R.F.; Prokopczyk, I.M.; Zottis, A.; Oliva, G.; Andricopulo, A.D.; Trevisan, M.T.; Vilegas, W.; Silva, M.G.; Montanari, C.A. Discovery of novel Trypanosoma cruzi glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2009, 17, 2476–2482.

- Paramashivappa, R.; Phani Kumar, P.; Subba Rao, P.V.; Srinivasa Rao, A. Synthesis of sildenafil analogues from anacardic acid and their phosphodiesterase-5 inhibition. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 7709–7713.

- Paramashivappa, R.; Phani Kumar, P.; Subba Rao, P.V.; Srinivasa Rao, A. Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of benzimidazole/benzothiazole and benzoxazole derivatives as cyclooxygenase inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2003, 13, 657–660.

- Rekowski, M.; Giannis, A. Histone acetylation modulation by small molecules: A chemical approach. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2010, 1799, 760–767.

- Sbardella, G.; Castellano, S.; Vicidomini, C.; Rotili, D.; Nebbioso, A.; Miceli, M.; Altucci, L.; Mai, A. Identification of long chain alkylidenemalonates as novel small molecule modulators of histone acetyltransferases. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2008, 18, 2788–2792.

- Mai, A.; Rotili, D.; Tarantino, D.; Nebbioso, A.; Castellano, S.; Sbardella, G.; Tini, M.; Altucci, L. Identification of 4-hydroxyquinolines inhibitors of p300/CBP histone acetyltransferases. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009, 19, 1132–1135.

- Chandregowda, V.; Kush, A.; Reddy, G.C. Synthesis of benzamide derivatives of anacardic acid and their cytotoxic activity. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 44, 2711–2719.

- Hundt, J.; Li, Z.; Liu, Q. The inhibitory effects of anacardic acid on hepatitis C virus life cycle. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0117514.

- Proschak, E.; Heitel, P.; Kalinowsky, L.; Merk, D. Opportunities and Challenges for Fatty Acid Mimetics in Drug Discovery. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60, 5235–5266.

- Stasiuk, M.; Bartosiewicz, D.; Kozubek, A. Inhibitory effect of some natural and semisynthetic phenolic lipids upon acetylcholinesterase activity. Food Chem. 2008, 108, 996–1001.

- Stasiuk, M.; Janiszewska, A.; Kozubek, A. Phenolic lipids affect the activity and conformation of acetylcholinesterase from Electrophorus electricus (Electric eel). Nutrients 2014, 6, 1823–1831.

- Sussman, J.L.; Harel, M.; Frolow, F.; Oefner, C.; Goldman, A.; Toker, L.; Silman, I. Atomic structure of acetylcholinesterase from Torpedo californica: A prototypic acetylcholine-binding protein. Science 1991, 253, 872–879.

- Ordentlich, A.; Barak, D.; Kronman, C.; Flashner, Y.; Leitner, M.; Segall, Y.; Ariel, N.; Cohen, S.; Velan, B.; Shafferman, A. Dissection of the human acetylcholinesterase active center determinants of substrate specificity. Identification of residues constituting the anionic site, the hydrophobic site, and the acyl pocket. J. Biol. Chem. 1993, 268, 17083–17095.

- De Paula, A.A.N.; Martins, J.B.L.; Gargano, R.; dos Santos, M.L.; Romeiro, L.A.S. Electronic structure calculations toward new potentially AChE inhibitors. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2007, 446, 304–308.

- De Paula, A.A.; Martins, J.B.; dos Santos, M.L.; Nascente, L.E.C.; Romeiro, L.A.; Areas, T.F.; Vieira, K.S.; Gambôa, N.F.; Castro, N.G.; Gargano, R. New potential AChE inhibitor candidates. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 44, 3754–3759.

- Lemes, L.F.N.; de Andrade Ramos, G.; de Oliveira, A.S.; da Silva, F.M.R.; de Castro Couto, G.; da Silva Boni, M.; Guimarães, M.J.R.; Souza, I.N.O.; Bartolini, M.; Andrisano, V.; et al. Cardanol-derived AChE inhibitors: Towards the development of dual binding derivatives for Alzheimer’s disease. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 108, 687–700.

- Bolognesi, M.L.; Minarini, A.; Rosini, M.; Tumiatti, V.; Melchiorre, C. From dual binding site acetylcholinesterase inhibitors to multi-target-directed ligands (MTDLs): A step forward in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2008, 8, 960–967.

- Cavalli, A.; Bolognesi, M.L.; Capsoni, S.; Andrisano, V.; Bartolini, M.; Margotti, E.; Cattaneo, A.; Recanatini, M.; Melchiorre, C. A small molecule targeting the multifactorial nature of Alzheimer’s disease. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2007, 46, 3689–3692.

- Rampa, A.; Belluti, F.; Gobbi, S.; Bisi, A. Hybrid-based multi-target ligands for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2011, 11, 2716–2730.

- Rosini, M.; Simoni, E.; Bartolini, M.; Tarozzi, A.; Matera, R.; Milelli, A.; Hrelia, P.; Andrisano, V.; Bolognesi, M.L.; Melchiorre, C. Exploiting the lipoic acid structure in the search for novel multitarget ligands against Alzheimer’s disease. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 46, 5435–5442.

- Bolognesi, M.L.; Bartolini, M.; Tarozzi, A.; Morroni, F.; Lizzi, F.; Milelli, A.; Minarini, A.; Rosini, M.; Hrelia, P.; Andrisano, V.; et al. Multitargeted drugs discovery: Balancing anti-amyloid and anticholinesterase capacity in a single chemical entity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011, 21, 2655–2658.

- Melchiorre, C.; Bolognesi, M.L.; Minarini, A.; Rosini, M.; Tumiatti, V. Polyamines in drug discovery: From the universal template approach to the multitarget-directed ligand design strategy. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 53, 5906–5914.

- De Abreu Silva, M.; Sette, C.D.A.B.; Kiametis, A.S.; Romeiro, L.A.S.; Gargano, R. Molecular modeling of cardanol-derived AChE inhibitors. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2019, 731, 136591.

- De Andrade Ramos, G.; Souza de Oliveira, A.; Bartolini, M.; Naldi, M.; Liparulo, I.; Bergamini, C.; Uliassi, E.; Wu, L.; Fraser, P.E.; Abreu, M.; et al. Discovery of sustainable drugs for Alzheimer’s disease: Cardanol-derived cholinesterase inhibitors with antioxidant and anti-amyloid properties. RSC Med. Chem. 2021, 12, 1154–1163.

- Hemshekhar, M.; Sebastin Santhosh, M.; Kemparaju, K.; Girish, K.S. Emerging roles of anacardic acid and its derivatives: A pharmacological overview. Basic Clin. Pharm. Toxicol. 2012, 110, 122–132.

- Soares Romeiro, L.A.; da Costa Nunes, J.L.; de Oliveira Miranda, C.; Simões Heyn Roth Cardoso, G.; de Oliveira, A.S.; Gandini, A.; Kobrlova, T.; Soukup, O.; Rossi, M.; Senger, J.; et al. Novel Sustainable-by-Design HDAC Inhibitors for the Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2019, 10, 671–676.

- De Souza, M.Q.; Teotônio, I.M.S.N.; de Almeida, F.C.; Heyn, G.S.; Alves, P.S.; Romeiro, L.A.S.; Pratesi, R.; de Medeiros Nóbrega, Y.K.; Pratesi, C.B. Molecular evaluation of anti-inflammatory activity of phenolic lipid extracted from cashew nut shell liquid (CNSL). BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2018, 18, 181.

- Gomes Júnior, A.L.; Islam, M.T.; Nicolau, L.A.D.; de Souza, L.K.M.; Araújo, T.S.L.; Lopes de Oliveira, G.A.; de Melo Nogueira, K.; da Silva Lopes, L.; Medeiros, J.R.; Mubarak, M.S.; et al. Anti-Inflammatory, Antinociceptive, and Antioxidant Properties of Anacardic Acid in Experimental Models. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 19506–19515.

- Morphy, R.; Rankovic, Z. Designed multiple ligands. An emerging drug discovery paradigm. J. Med. Chem. 2005, 48, 6523–6543.

More