Bronchoscopy has several major diagnostic and therapeutic indications in pulmonology. However, it is an aerosol-generating procedure that places healthcare providers at an increased risk of infection. Now more than ever, during the spread of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, the infectious risk during bronchoscopy is significantly raised, and for this reason its role in diagnostic management is debated.

1. Introduction

The gold standard diagnostic tests for detecting current SARS-CoV-2 infections are based on reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) with samples collected from the upper respiratory tract (nasopharyngeal nasal or oropharyngeal swabs) [1][7]. Indeed, in the prodromal phase, when the contagiousness is higher, the active viral replication of the virus can be localized and identified in the upper airways [2][8]. However, these tests do not have high sensitivity, ranging from 32 to 63% due to wrong handling of the specimen, sample collection during the late phase of the disease, or low viral load [3][4][9,10]. Among patients with clinical suspicion of COVID-19, with negative nasopharyngeal swabs, samples from the lower respiratory tract using bronchoscopy could increase sensitivity and help to achieve a correct diagnosis. Indeed, Wang and colleagues compared positive RT-PCR tests on different clinical specimens in patients with COVID-19 and showed that bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) was positive in 93% of cases, compared to sputum (72%), nasal (63%), and pharyngeal swab (32%) [4][10].

2. Role of Bronchoscopy in the DiManagnostic Work-up oement of COVID-19 Infection

T

During the

rolpande

of bronchoscopy in COVID-19 is still a matter of vivid debate, in particular given the high contagious risk of the procedure. The reasons are mostly due to the significant amounts of droplets that contaminate the indoor equipmmic, patient management varied based on the severity of respiratory failure. Indeed, when a low-flow oxygen supplementation through nasal cannula or face mask was required, patients were managed in a low-intensity medical care (LIMC) ward, such as internal medicine or infectious disease unit. Conversely, when these strategies were not sufficient and

the procedure room’s air, the increased pressures ushigh-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) or invasive/non-invasive ventilation were needed, patients were admitted to

oxygenate or ventilate the patients with rhigh-intensity medical care (HIMC) wards, such as a Respiratory

failure,Intensive Care Unit (RICU) or ICU [23]. aIn

d especially the close contact between the medical personnel involved in the procedure and the patient [5].

A the setting of critically ill patients, bronchoscopy had a particularly important role. Indeed, in those who require non-invasive or invasive ventilation, several complications may occur, thus hampering the effectiveness of ventil

at

hough many scientific societies have issued guidelines in order to reduce heterogeneity in clinical practiceion. For instance, lobar atelectasis is a potential acute complication of severe COVID-19 that is generally determined by the presence of mucus plugs and is associated with poor outcomes [6][24].

Similarly,

the

scientific background supporting bronchoscopy is poor and mainlmoptysis or bloody mucus from the lower respiratory tract, which may comp

osed of case serieslicate the most [7][8][9].

Iadvan

thce

National Institute of Health d and severe forms of COVID-19

treatmentwith a high mortality rate [25], gui

delines panel (last updated on August 21)s another cause of ineffective ventilation because of [1],complete bronch

ial o

scopy with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) of the lower respiratory tract is only indicated in patientsbstruction. Conversely, the presence of diffuse mucosal hyperemia is typical of an earlier phase of COVID-19 that indicates a potentially reversible acute inflammation associated with

clinical signs reduced in-hospital mortality rates [26].

Mechan

ically ventilated

symptoms consistentpatients with COVID-19

pneumonia but a negative upper respiratory tract swab in order to confirm or exclude a diagnosis ofare prone to develop ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) that could be unrecognized because of its clinical and radiographic similarity to COVID-19

, even though. VAP has an incidence ranging from 29 up to 80% [27,28] in the

y s

uggested that endotracheal aspirates should be preferred over BAL whenever possible.

Variouse patients, with a hazard ratio of 2.1 compared to that in types no

f n-COVID-19

diagnostipatients [29]. Suc

h guidance have been proposed by high incidence may be due to several

Endoscopic and Pulmonologists Societies during the pandemicfactors, such as the treatment-associated immune impairment and prolonged mechanical [5][10][11][12][13][14], whventilati

chon recommendedor sedation. In those cases, bronchoscopy

in suspected COVID-19 casesmight help to formulate the correct diagnosis.

With foregar

typical clinical and radiological features but with a concomitant negative oropharyngeal swab. However, itd to superimposed infections, fungal co-infection has an incidence of up to 34% in COVID-19 patients hospitalized in the ICU. In this case, COVID-19 associated pulmonary aspergillosis (CAPA) has a mortality rate of 36% [30]. Si

s not clearly specified how many negative samples are required to support the indication.

Oramilar to COVID-19, pulmonary aspergillosis may manifest with fever, dyspnea, or respiratory failure and pulmonary infiltrates. Therefore, the diagnosis of CAPA J.is and co-workers investigatedbased on microbiological criteria, and BAL analysis is an important tool in this

issue aregard [30].

Endoscopic suggested that three negative swabs, performed on three consecutive days, along with negative serology, despite highlyexamination through bronchoscopy may also reveal the presence of lesions (i.e., epithelial plaques, pseudomembranes, or ulceration of the bronchial mucosa) that may not be detectable by radiologic exams. We observed these findings in one patient with COVID-19 (Figure 1). Thesuggestive clinical features and a computed tomoge lesions resembled lung cancer infiltration and only bronchial biopsy allowed a correct diagnosis of CAPA.

Figure 1. Evidence of mucosal infiltration and pseudomembranes in the left main bronchus, in a COVID-19 associated pulmonary aspergillosis (CAPA). The patient underwent a bronchial biopsy for the histological diagnosis.

In HIMC war

apds, wh

y (CT) scan, can safely rule out the SARS-CoV-2 infection [15]ere non-invasive/invasive ventilation is performed, pneumomediastinum is an additional frequent complication, despite the use of protective ventilation. Indeed,

in a

ll BALF obtained in this population were negative for SARS-CoV-2 virus, but showed, in nearly half study that compared the incidence of pneumomediastinum in ARDS secondary to COVID-19 to that of other causes, the authors observed a higher incidence of pneumomediastinum in COVID-19 ARDS patients (13.6% vs. 1.9%, p < 0.001) [31]. ofIn the

m, a different isol management of this complication,

hence allowing an bronchoscopy can identify the presence of bronchial or tracheal injury.

Apa

lrt

ernative diagnosis from the complications of [15]. COVID-19 men another study that evaluated a populationtioned above, bronchoscopy has a role in the management of patients with similar clinical characteconditions not related to COVID-19.

Duri

sng t

ics, but with only two consecutive negative nasopharyngeal swabs, a low diagnostic yield of BALF for detecting SARS-CoV-2 virus (36%) was reporthe pandemic, most of the elective bronchoscopies have been suspended or rescheduled; indeed patients have been stratified according to emergent or urgent indications, as defined

[16].

Tby the

s American College

results are in contrasof Chest Physicians and the American Association for Bronchology and Interventional Pulmonology (CHEST/AABIP) [24].

Emergent

windi

th other studies, incations were life-saving procedures, which

BALF helped in determining COVID-19 diagnosis with higher rates reported, ranging from 55 to 93%could not be delayed, such as moderate symptomatic or worsening tracheal/bronchial stenosis, symptomatic central airway obstruction, and migrated stent [24] [3][7][15](Table 1).

Table 1. Indications for bronchoscopy in suspected COVID-19 and indication for urgent or emergent in confirmed COVID-19 during the pandemic peak.

Urgent Thindicatis could be in part explained by a lower number (one or two) of oro/nasopharyngeal swabs previously performed.

Overall,ons include lung cancer diagnosis (lung mass or mediastinal/hilar lymphadenopathy), foreign body aspiration, and suspected pulmonary infection in immunocompromised pas mosttients (Table 1). ofIn the studies showed, one of the leading roles of bronchoscopy in this context is to identify potential alternative infections or coinfections, in particular inlatter case, early bronchoscopy is essential because it may rule out the presence of a co-infection, thus allowing timely treatment. Moreover, in patients that underwent lung transplantation, transbronchial biopsies have an important role in identifying the presence of acute cellular rejection. immunFigure 2 showsuppress the CT scan of a transplanted patients. Interestingly, recent studies reported alternative infectious diseases in who was infected by SARS-CoV-2 during the recovery after lung transplant. The persistence of consolidations in the right lower lobe despite treatment for COVID-19 suggested a possible acute cellular rejection. However, the patient was histologically diagnosed with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia.

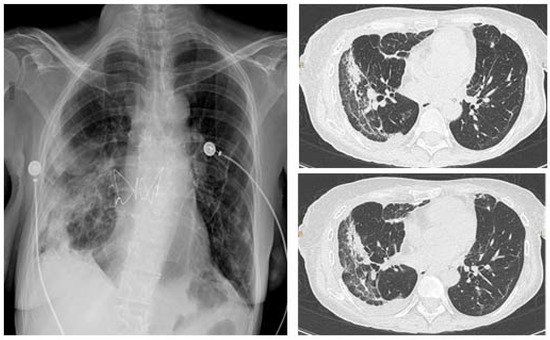

Figure 2. Chest X-ray (CXR) (left), CT scan (right) of a lung transplanted patient who was infected by SARS-CoV-2 during the recovery after transplant. The patient underwent a tranbronchial bronchial biopsy and was histologically diagnosed with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia.

Bronchoscopy du

p to 65% of patients, causing a change in the pharmacological care of the diseasering the pandemic was also useful in other scenarios. In our institution, apart from the emergent/urgent indications mentioned above, we performed bronchoscopy in a patient with COVID-19 that underwent a left [7][15].

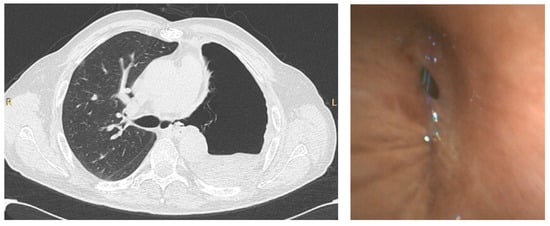

Thpneumonectomy diagnostic limits of oro/nasopharyngeal swabs could be offset by chest CT featuresfor lung cancer, to investigate the presence of a bronchopleural fistula, which was confirmed, in order to decide the best therapeutic intervention (Figure 3).

Figure 3. CT scan (left) of a patient that underwent left pneumonectomy, showing a possible left bronchopleural fistula, in a COVID-19 positive patient, confirmed by bronchoscopy (right) using single-use flexible bronchoscope.

In addition,

BAL which showed a sensitivity of 97% in suspectedmay have a prognostic role; indeed, the identification of an extensive alveolitis in COVID-19

casespatients, particularly in the presence [3];of h

owigh leve

r, to date, the lack of standardized diagnostic algls of IL6 and IL8, correlates with the severity of the disease and predict clinical outcomes [32].

As sho

wn, br

ithms including clinical and radiologic features together with RT-PCR results might beonchoscopy, and especially BAL, may have multiple indications. However, during the pandemic peak, patients had to be carefully selected not only for the r

eason of requesting not properly further invasive procedure such as bronchoscopyisk of contagion for the healthcare personnel, but also for the patients given the risk of further deteriorating respiratory failure [33].

3. Role of Bronchoscopy in the Management of COVID-19 Infection

During the pandemic, patient management varied based on the severity of respiratory failure. Indeed, when a low-flow oxygen supplementation through nasal cannula or face mask was required, patients were managed in a low-intensity medical care (LIMC) ward, such as internal medicine or infectious disease unit. Conversely, when these strategies were not sufficient and high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) or invasive/non-invasive ventilation were needed, patients were admitted to high-intensity medical care (HIMC) wards, such as a Respiratory Intensive Care Unit (RICU) or ICU

[17][23]. In the setting of critically ill patients, bronchoscopy had a particularly important role. Indeed, in those who require non-invasive or invasive ventilation, several complications may occur, thus hampering the effectiveness of ventilation. For instance, lobar atelectasis is a potential acute complication of severe COVID-19 that is generally determined by the presence of mucus plugs and is associated with poor outcomes

[18][24].

Similarly, hemoptysis or bloody mucus from the lower respiratory tract, which may complicate the most advanced and severe forms of COVID-19 with a high mortality rate

[19][25], is another cause of ineffective ventilation because of complete bronchial obstruction. Conversely, the presence of diffuse mucosal hyperemia is typical of an earlier phase of COVID-19 that indicates a potentially reversible acute inflammation associated with reduced in-hospital mortality rates

[20][26].

Mechanically ventilated patients with COVID-19 are prone to develop ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) that could be unrecognized because of its clinical and radiographic similarity to COVID-19. VAP has an incidence ranging from 29 up to 80%

[21][22][27,28] in these patients, with a hazard ratio of 2.1 compared to that in non-COVID-19 patients

[23][29]. Such high incidence may be due to several factors, such as the treatment-associated immune impairment and prolonged mechanical ventilation or sedation. In those cases, bronchoscopy might help to formulate the correct diagnosis.

With regard to superimposed infections, fungal co-infection has an incidence of up to 34% in COVID-19 patients hospitalized in the ICU. In this case, COVID-19 associated pulmonary aspergillosis (CAPA) has a mortality rate of 36%

[24][30]. Similar to COVID-19, pulmonary aspergillosis may manifest with fever, dyspnea, or respiratory failure and pulmonary infiltrates. Therefore, the diagnosis of CAPA is based on microbiological criteria, and BAL analysis is an important tool in this regard

[24][30].

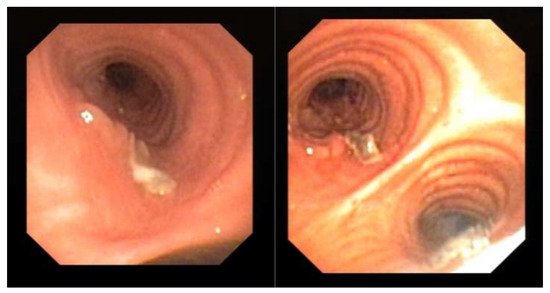

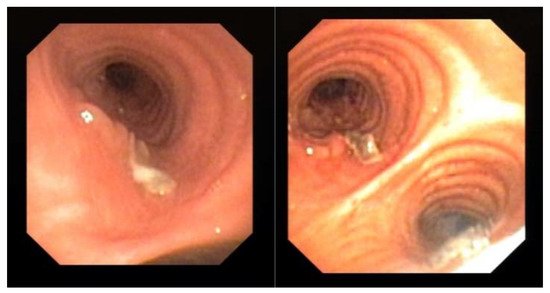

Endoscopic examination through bronchoscopy may also reveal the presence of lesions (i.e., epithelial plaques, pseudomembranes, or ulceration of the bronchial mucosa) that may not be detectable by radiologic exams. We observed these findings in one patient with COVID-19 (Figure 1). These lesions resembled lung cancer infiltration and only bronchial biopsy allowed a correct diagnosis of CAPA.

Figure 1. Evidence of mucosal infiltration and pseudomembranes in the left main bronchus, in a COVID-19 associated pulmonary aspergillosis (CAPA). The patient underwent a bronchial biopsy for the histological diagnosis.

In HIMC wards, where non-invasive/invasive ventilation is performed, pneumomediastinum is an additional frequent complication, despite the use of protective ventilation. Indeed, in a study that compared the incidence of pneumomediastinum in ARDS secondary to COVID-19 to that of other causes, the authors observed a higher incidence of pneumomediastinum in COVID-19 ARDS patients (13.6% vs. 1.9%,

p < 0.001)

[25][31]. In the management of this complication, bronchoscopy can identify the presence of bronchial or tracheal injury.

Apart from the complications of COVID-19 mentioned above, bronchoscopy has a role in the management of patients with conditions not related to COVID-19.

During the pandemic, most of the elective bronchoscopies have been suspended or rescheduled; indeed patients have been stratified according to emergent or urgent indications, as defined by the American College of Chest Physicians and the American Association for Bronchology and Interventional Pulmonology (CHEST/AABIP)

[18][24].

Emergent indications were life-saving procedures, which could not be delayed, such as moderate symptomatic or worsening tracheal/bronchial stenosis, symptomatic central airway obstruction, and migrated stent

[18][24] (

Table 1).

Table 1. Indications for bronchoscopy in suspected COVID-19 and indication for urgent or emergent in confirmed COVID-19 during the pandemic peak.

| Suspected COVID-19 |

Confirmed COVID-19:

Emergent Indication |

Confirmed COVID-19:

Urgent Indication |

| Confirm or exclude COVID-19 in those with a negative upper respiratory tract swab, but clinical signs and symptoms consistent for COVID-19 pneumonia [1] |

Moderate symptomatic or worsened tracheal/bronchial stenosis; migrated stent |

Lung cancer diagnosis (lung mass or mediastinal/hilar lymphadenopathy) |

| Confirm suspected COVID-19 cases with a negative upper respiratory tract swab, but typical clinical and radiological features [5][9][10][11][12][13][14] |

Symptomatic central airway obstruction (i.e., due to mucus plug) or lobar atelectasis |

Foreign object aspiration |

| Confirm or exclude COVID-19 in those with a negative upper respiratory tract swab and clinical signs and symptoms possible for COVID-19 pneumonia, but an alternative diagnosis could also be considered [1] |

Hemoptysis or bloody mucus from the lower respiratory tract |

Suspected concomitant pulmonary infection in immunosuppressed patients (i.e., fungal co-infection) |

Indications for bronchoscopy in suspected COVID-19 and indication for urgent or emergent in confirmed COVID-19 during the pandemic peak.

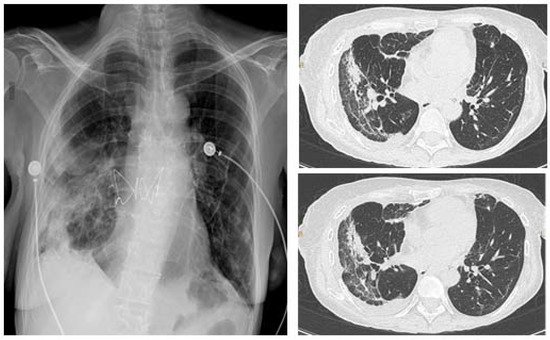

Urgent indications include lung cancer diagnosis (lung mass or mediastinal/hilar lymphadenopathy), foreign body aspiration, and suspected pulmonary infection in immunocompromised patients (Table 1). In the latter case, early bronchoscopy is essential because it may rule out the presence of a co-infection, thus allowing timely treatment. Moreover, in patients that underwent lung transplantation, transbronchial biopsies have an important role in identifying the presence of acute cellular rejection. Figure 2 shows the CT scan of a transplanted patient who was infected by SARS-CoV-2 during the recovery after lung transplant. The persistence of consolidations in the right lower lobe despite treatment for COVID-19 suggested a possible acute cellular rejection. However, the patient was histologically diagnosed with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia.

Figure 2. Chest X-ray (CXR) (left), CT scan (right) of a lung transplanted patient who was infected by SARS-CoV-2 during the recovery after transplant. The patient underwent a tranbronchial bronchial biopsy and was histologically diagnosed with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia.

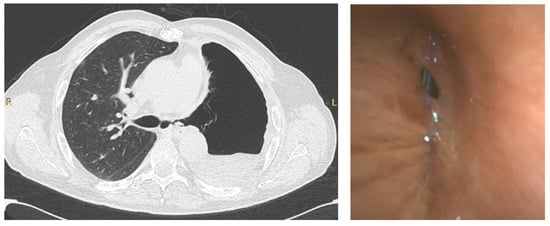

Bronchoscopy during the pandemic was also useful in other scenarios. In our institution, apart from the emergent/urgent indications mentioned above, we performed bronchoscopy in a patient with COVID-19 that underwent a left pneumonectomy for lung cancer, to investigate the presence of a bronchopleural fistula, which was confirmed, in order to decide the best therapeutic intervention (Figure 3).

Figure 3. CT scan (left) of a patient that underwent left pneumonectomy, showing a possible left bronchopleural fistula, in a COVID-19 positive patient, confirmed by bronchoscopy (right) using single-use flexible bronchoscope.

In addition, BAL may have a prognostic role; indeed, the identification of an extensive alveolitis in COVID-19 patients, particularly in the presence of high levels of IL6 and IL8, correlates with the severity of the disease and predict clinical outcomes

[26][32].

As shown, bronchoscopy, and especially BAL, may have multiple indications. However, during the pandemic peak, patients had to be carefully selected not only for the risk of contagion for the healthcare personnel, but also for the patients given the risk of further deteriorating respiratory failure

[27][33].