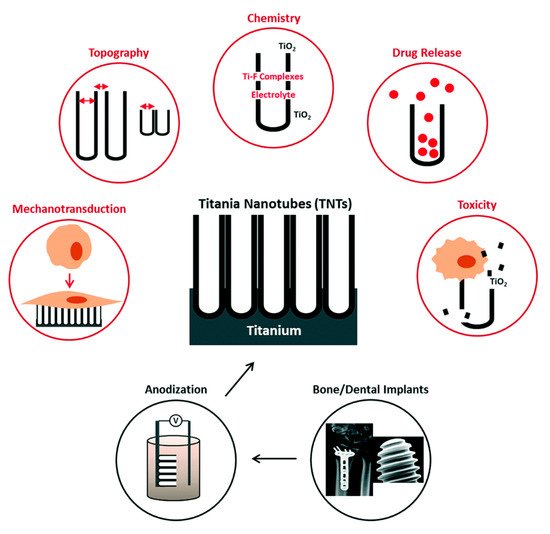

Titanium (Ti) and its alloys offer favorable biocompatibility, mechanical properties and corrosion resistance, which makes them an ideal material choice for dental implants. However, the long-term success of Ti-based dental implants may be challenged due to implant-related infections and inadequate osseointegration. With the development of nanotechnology, nanoscale modifications and the application of nanomaterials have become key areas of focus for research on dental implants. Surface modifications and the use of various coatings, as well as the development of the controlled release of antibiotics or proteins, have improved the osseointegration and soft-tissue integration of dental implants, as well as their antibacterial and immunomodulatory functions. This review introduces recent nano-engineering technologies and materials used in topographical modifications and surface coatings of Ti-based dental implants. These advances are discussed and detailed, including an evaluation of the evidence of their biocompatibility, toxicity, antimicrobial activities and in-vivo performances. The comparison between these attempts at nano-engineering reveals that there are still research gaps that must be addressed towards their clinical translation. For instance, customized three-dimensional printing technology and stimuli-responsive, multi-functional and time-programmable implant surfaces holds great promise to advance this field. Furthermore, long-term in vivo studies under physiological conditions are required to ensure the clinical application of nanomaterial-modified dental implants.

- dental implants

- Nano-Engineering

- osseointegration

- TiO2 nanotubes

- surface modification

- nanoparticles

- antibacterial