Authors: Joshua Hadi, Shuyan Wu, Aswathi Soni, Amanda Gardner, Gale Brightwell

Antimicrobial blue light treatments have mostly been utilized in clinical and food settings. The treatment involves the exposure of bacteria in a given matrix to blue light that can be absorbed by endogenous porphyrins within the bacterial cell, inducing the production of reactive oxygen species, which subsequently inflict oxidative damages upon different cellular components. The efficacy of antimicrobial blue light treatments is most commonly measured by the reduction in bacterial counts after exposure to a certain light dosage (Joule/cm^2), defined as the multiplication product of light intensity and treatment time. Inherent factors may confer protection to a selected group of bacteria against blue light-induced oxidative damages or modulate the physiological characteristics of the treated bacteria, such as virulence and motility.

- antimicrobial blue light

- blue light photoreceptor

- blue light-sensing chemoreceptor

- SOS-dependent DNA repair

- antimicrobial resistance

1. Introduction

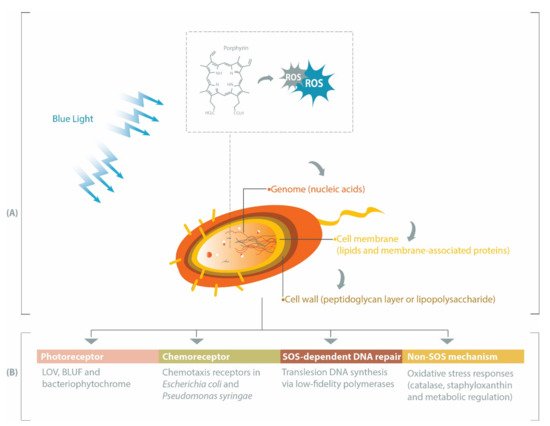

While UV light has been extensively investigated and has demonstrated success in microbial inactivation strategies, visible light is less harmful than UV [1][7]. Within the visible spectrum, blue light at the wavelength range of 400–450 nm has the highest bactericidal property associated with its absorbance by endogenous porphyrins, leading to cell death [2][3][2,8]. Porphyrins are intermediate species in the heme biosynthesis [4][5][9,10] and may be activated by blue light to produce reactive oxygen species (ROS), such as superoxide, hydrogen peroxide, hydroxyl radicals, and reactive singlet oxygen [6][11]. These ROS can subsequently induce oxidative stress upon different bacterial cell constituents, especially genomic materials, cell membrane, and cell wall (Figure 1 A). Prokaryotic genomes can be degraded by ROS during blue light treatments [7][8][12,13], particularly through the oxidation of guanine residues into 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine [7][12]. Fatty acids within the bacterial cell membrane are susceptible to blue light-induced oxidation, commonly marked by the formation of malondialdehyde [9][10][14,15]. Breakage of the bacterial cell wall has been reported in Gram-positive MRSA [11][16] and Gram-negative Acinetobacter baumannii [12][17], and inactivation of Escherichia coli lipopolysaccharide has also been observed in vitro [13][18].

Furthermore, the efficacy of antimicrobial blue light extends to non-planktonic bacteria. Fila et al. demonstrated blue light-mediated inhibition of the quorum sensing signalling systems in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, leading to the delayed formation of biofilm, and subsequently reduced pathogenicity in the animal model Caenorhabditis elegans [14][19]. Besides nucleic acids, proteins, and lipids [14][15][16][19,20,21], polysaccharide materials contained within the biofilm matrix could also be targeted by antimicrobial blue light, albeit only when an exogenous photosensitizer (i.e., photoactive compounds, such as porphyrins) is applied [17][22].

Antimicrobial blue light treatments have mostly been utilized in clinical and food settings [18][19][23,24]. It involves the exposure of bacteria in a given matrix to a blue light source (for example, light-emitting diodes) at a fixed light intensity (Watt/cm 2) for a period of treatment time (second). The efficacy of antimicrobial blue light treatments is most commonly measured by the reduction in bacterial counts after exposure to a certain light dosage (Joule/cm 2), defined as the multiplication product of light intensity and treatment time. Importantly, sensitivities to blue light vary across bacterial strains, i.e., the light dosage required to inactivate different strains may vary considerably [20][21][22][25,26,27]. Thus, as with other antimicrobial treatments, antimicrobial blue light may be applied in an insufficient amount (i.e., sub-lethal), potentially resulting in the development of tolerance [23][28]. However, the underlying mechanism of this phenomenon remains elusive and this represents an important research gap that needs to be addressed to improve future designs of blue light-based antimicrobial treatments, particularly in deciding whether complementary treatments are necessary.

In this review, we summarize several pathways affecting bacterial responses to blue light, including when the blue light is applied at different growth temperatures, sub-lethal dosage or against varying forms of bacteria (planktonic, biofilm or spore). Beginning with the description of genes involved in the production of endogenous porphyrins, we subsequently discuss the roles of photoreceptors, chemoreceptors, and DNA repair-related genes in eliciting protective pathways against oxidative stress or in modulating bacterial physiological characteristics under blue light illumination (Figure 1 B).

2. Porphyrin, Bacteria and Antimicrobial Blue Light

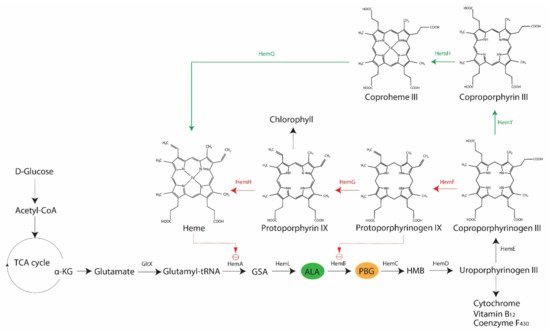

It is an established fact that various bacteria synthesize porphyrins within their cell and that the type and levels of porphyrins may vary across species [18][23]. The two most relevant porphyrins are protoporphyrin IX and coproporphyrin (I and III), as their involvements in antimicrobial blue light treatments have been demonstrated in both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, such as S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, A. baumannii, and Helicobacter pylori [24][25][26][27][29,30,31,32]. However, there is also evidence of differing sensitivities to blue light between Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, primarily due to the varying levels of coproporphyrin produced in the two bacterial types [24][29]. In bacteria, the core pathway of 5-carbon heme biosynthesis usually begins with a charged glutamyl-tRNA that undergoes a series of enzymatic conversion processes to form coproporphyrinogen III via the universal intermediate species δ-aminolevulinic acid (ALA), also known as 5-aminolevulinic acid (Figure 2). At this point, two possible branches emerge from the core pathway: (1) Gram-negative bacteria decarboxylate coproporphyrinogen III to protoporphyrinogen IX, oxidize protoporphyrinogen IX to protoporphyrin IX and then add metal to form protoheme; (2) Gram-positive bacteria oxidize coproporphyrinogen III to coproporphyrin, insert iron to make coproheme and oxidize coproheme to protoheme [4][5][9,10]. Alphaproteobacteria possess ALA synthase and may undergo heme biosynthesis via the non-canonical 4-carbon pathway, in which glutamyl-tRNA is replaced by a compound derived from the combination of succinyl CoA from the tricarboxylic acid cycle and glycine [4][9].

The rate-limiting compound in heme biosynthesis is ALA, which acts as the committed precursor that leads to the formation of the tetrapyrrole structure of porphyrins [4][9]. Expectedly, external addition of ALA to light treatments has been reported to increase the production of porphyrins in S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, and E. coli (strain K-12 and Ti05), and subsequently render these bacteria more susceptible to light-based antimicrobial treatments [29][30][34,35]. Downstream of ALA, various enzymes are involved in the conversion of one tetrapyrrole structure to another, leading to the formation of different photoactive porphyrins (Figure 2). In addition to their respective functions in the forward reaction of heme biosynthesis, some of these enzymes are involved in feedback regulations, as demonstrated in E. coli, where the overexpression of hemD and hemF resulted in the accumulation of ALA, whereas hemB, hemG and hemH had a negative effect on ALA production [28][33]. The inhibition of HemB by protoporphyrin IX also occurs in E. coli [28][33]. Furthermore, there are other regulatory mechanisms in heme biosynthesis, including hemA -related regulations in E. coli, Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhimurium, Bacillus subtilis, and P. aeruginosa or oxygen-dependent regulations of coproporphyrinogen oxidase genes (i.e., hemF or hemN ) in Pseudomonas spp., E. coli, and B. subtilis [5][10]. These findings indicate the possibility of variations in porphyrin species present at any given point, which could also be influenced by growth conditions.

Porphyrin production has been suggested to depend on the bacterial growth stage. In Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans and Pophyromonas gingivalis, the amounts of coproporphyrin (I and III) and protoporphyrin IX are highest in the first few days of growth, although variations have been observed across different types of porphyrins and bacterial strains [31][36]. Growth media could also impact porphyrin production, for example, P. gingivalis colonies cultured on a medium containing blood was reported to have increased production of protoporphyrin IX, relative to colonies grown on a medium lacking blood [31][36]. Consistently, there is evidence of strain-specific and growth phase-dependent inactivation of MRSA and E. coli by blue light, possibly related to porphyrin production [32][33][37,38]. In addition, a study revealed a positive correlation between ALA-mediated production of porphyrin species (protoporphyrin IX, coproporphyrin III, and uroporphyrin III) and elevated growth temperatures (up to 42 °C) in Propionibacterium acnes [34][39]. Nevertheless, there is still a need for further characterizations of endogenous porphyrins in other bacteria, along with assessments of their sensitivity to blue light, at different growth phases and temperatures. These data are particularly relevant for ensuring the appropriate design and application of blue light treatments, given that the relative absorption spectra of different porphyrin species vary. For example, protoporphyrin IX and uroporphyrin III absorb blue light at approximately 405–420 nm, whereas coproporphyrin III has the highest absorption at approximately 390 nm [35][40].

3. Heme Non-Producing Bacteria: Antimicrobial Blue Light or Photodynamic Therapy

Lactic acid bacteria (LAB), including pathogenic species belonging to the genera Streptococcus and Enterococcus, are not reliant upon heme for growth and thus unable to synthesize this cofactor, i.e., porphyrins are not prevalent in this group of bacteria [36][41]. Two studies have demonstrated that Enterococcus faecalis (formerly known as Streptococcus faecalis group D) and Enterococcus faecium devoid of porphyrins were insensitive to blue light-based antimicrobial treatments at 407–420 nm and 405 nm, respectively [24][37][29,42].

Intriguingly, others have reported on the inactivation of E. faecium by antimicrobial treatments with D 90-values (light dosage required to obtain a 1-log inactivation) of 393 or 595 J/cm 2 at 400 or 405 nm, respectively, which were considerably higher than other tested strains in both studies [20][38][25,43]. Insoluble fractions of the extracellular polymeric substance within Streptococcus mutans biofilms were also found to be susceptible to antimicrobial blue light (420 nm) [15][20]. However, the bactericidal mechanism of blue light against heme non-producing bacteria at these shorter wavelengths (400–420 nm) is yet unknown. In contrast, flavins are known to absorb blue light at longer wavelengths (450–460 nm), resulting in the inactivation of various bacterial species, including E. faecium, albeit with lower efficacy than the conventional 405 nm antimicrobial blue light [38][39][40][43,44,45].

Alternative technology is also available in the form of antimicrobial photodynamic therapy (aPDT), which combines antimicrobial lights and photoactive compounds known as photosensitizers. Upon activation by light, photosensitizers at a ground state (lowest energy level) are converted into their excited singlet state (short-lived) or triplet state (long-lived), which, in the presence of oxygen, can undergo two types of energy transfer: (1) type I that produces toxic oxygen species, such as hydrogen peroxide (H 2O 2), superoxide or hydroxyl radicals; (2) type II that generates 1O 2 [6][11]. Various photosensitizers and their derivatives are known to exhibit absorption within the ultraviolet/blue light spectrum [41][46], several of which have been applied in aPDT against various heme non-producing bacteria (Table 1). For a given aPDT, selection of a suitable photosensitizer and blue light combination, along with the optimization of photosensitizer concentration, is paramount to achieve maximum bactericidal efficacy [37][42][43][44][45][42,47,48,49,50].

| Bacterial Species | Blue Light | Photosensitizer a | Light Dosage (Joule/cm2) *, a |

Bactericidal Efficacy **, a |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Streptococcus agalactiae | 450 nm (pulsed) | CP III (0.08 mg/mL) PP IX (0.08 mg/mL) |

7.6 | 8.89 log CFU/mL 9.54 log CFU/mL |

[47] |

| Streptococcus mutans | 360–550 nm | curcumin (2 µM) | 54 | 2 log cells *** | [48] |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae (planktonic or biofilm) | 405 nm | chlorin e6 (10 µM) | 12 or 90 | approximately 5 or 6.5 log CFU/mL | [49] |

| Enterococcus faecalis (planktonic or biofilm) |

405–500 nm | eosin Y (5 or 10 µM) rose bengal (1 or 2 µM) curcumin (5 or 1 µM) |

108 | 4.9 or 13.8 log CFU/mL 7.3 or 13.8 log CFU/mL 7.6 or 13.7 log CFU/mL |

[50] |

| Enterococcus faecium | 405 nm | curcumin (1 µg/mL) PP IX (0.1 µg/mL) |

25.3 | significant drop in optical density (655 nm) at p < 0.001 | [42] |

| Bacterial Species | Blue Light | Photosensitizer a | Light Dosage (Joule/cm2) *, a |

Bactericidal Efficacy **, a |

Reference |

| Streptococcus agalactiae | 450 nm (pulsed) | CP III (0.08 mg/mL) PP IX (0.08 mg/mL) |

7.6 | 8.89 log CFU/mL 9.54 log CFU/mL |

[42] |

| Streptococcus mutans | 360–550 nm | curcumin (2 µM) | 54 | 2 log cells *** | [43] |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae (planktonic or biofilm) | 405 nm | chlorin e6 (10 µM) | 12 or 90 | approximately 5 or 6.5 log CFU/mL | [44] |

| Enterococcus faecalis (planktonic or biofilm) |

405–500 nm | eosin Y (5 or 10 µM) rose bengal (1 or 2 µM) curcumin (5 or 1 µM) |

108 | 4.9 or 13.8 log CFU/mL 7.3 or 13.8 log CFU/mL 7.6 or 13.7 log CFU/mL |

[45] |

| Enterococcus faecium | 405 nm | curcumin (1 µg/mL) PP IX (0.1 µg/mL) |

25.3 | significant drop in optical density (655 nm) at p < 0.001 | [37] |

CP, coproporphyrin; PP, protoporphyrin; CFU, colony forming units. * Light dosage was calculated by multiplying light intensity (Watt/cm2) with treatment time (second). ** Bactericidal efficacy is defined as the reduction in the number of viable bacteria induced by antimicrobial blue light treatment. *** Number of bacterial cells was quantified by flow cytometry. a Photosensitizer concentrations, light dosages and bactericidal efficacies separated by the word “or” indicate differences between planktonic or biofilm cells.

4. Non-SOS Protective Mechanisms against Blue Light-Induced Oxidative Stress

Besides SOS-dependent pathways, several bacteria counteract blue light treatments by producing catalase, a ROS-scavenging enzyme. This enzyme is encoded by katA gene, which was found to be upregulated by 8-fold in S. aureus exposed to photo treatment at 462 nm and led to increased tolerance of the bacteria to hydrogen peroxide [46][156]. This is consistent with the findings of two other studies reporting increased tolerance to hydrogen peroxide in blue light-treated S. aureus [47][48][138,157]. Similarly, P. aeruginosa utilizes catalase to combat the photo-oxidative stress of blue light (464 nm), as evidenced by the higher susceptibility of mutants lacking katA to blue light than the wild-type [49][158]. Interestingly, one study demonstrated that blue light at 455 nm (225 J/cm 2) was able to completely inactivate the enzymatic activity of a recombinant P. aeruginosa catalase A (KatA) in vitro, albeit the direct implication of the reduced KatA activity upon the blue light inactivation of P. aeruginosa remains unclear [50][159].

Furthermore, S. aureus produces staphyloxanthin, a membrane-bound carotenoid pigment with antioxidant properties. In a recent study, S. aureus possessing the crtM gene, which is involved in the production of staphyloxanthin, exhibited a tolerant trait against blue light at 405 nm [51][160]. Thus, the authors proposed a pre-treatment of the tolerant S. aureus with blue light at 460 nm—which did not exhibit direct bactericidal activities but was capable of promoting the degradation of staphyloxanthin—resulting in the increased efficacy of the subsequent treatment with 405-nm blue light. In support of this finding, another study showed that exposure to blue light at 460 nm degraded staphyloxanthin and rendered methicillin-resistant S. aureus susceptible to subsequent treatments with oxidative agents [52][161].

As described in one study, Cronobacter sakazakii responded to blue light by upregulating three genes encoding an oxidative stress-resistance chaperone (ESA_RS13255), an adhesin (ESA_RS09025), and a capsule biosynthesis protein (ESA_RS15435), with the former promoting higher antioxidant activities [10][15]. For B. subtilis spores, resistance to blue light (400 nm) depends on the presence of DNA protective α/β-type small, acid-soluble proteins (SASP), DNA repair proteins (nucleotide or base excising repair proteins and spore photoproduct lyase), spore coat proteins and proteins for spore pigmentations—mutants lacking genes encoding these proteins were more susceptible to photoinactivation [53][162].

In V. cholerae, the blue light-mediated oxidative stress response is controlled by an anti-sigma ChrR (represses SigmaE) and metalloregulatory-like (MerR) proteins, either together or separately. Both proteins control 222 genes that are responsible for a range of functions, including cellular protection, DNA repair, and carbon metabolism [54][163]. Intriguingly, while cryptochrome/photolyase proteins are the sole blue-light photoreceptors in V. cholerae [55][164], these photoreceptors are not involved in the bacterial photo-oxidative responses, indicating a possible involvement of pigments or unknown photoreceptors in the V. cholerae stress response to blue light [54][163]. That being said, Tardu et al. did not analyze specific DNA repair pathways in V. cholerae, for example, photoreactivation involving the photolyase protein, and thus this is a subject of future studies.

Conclusion: The complex biological pathways involved in bacterial responses to antimicrobial blue light present challenges to be overcome. Endogenous porphyrin-mediated oxidative stress remains the primary mechanistic model of antimicrobial blue light. However, given the diversity of porphyrin species occurring at different stages of the heme biosynthesis, and thus corresponding to different blue light absorption spectra, it is paramount for future studies to assess the porphyrin biosynthesis pathway as a function of culture conditions, such as bacterial growth stage, growth media, and temperature. Subsequently, a correlation between bacterial growth stages, porphyrin species present and survival rate against antimicrobial blue light can be established. The mechanisms presented here highlight several inherent characteristics that set one bacterial species apart from another. Consequently, blue light inactivation parameters must be validated within the context of specific bacterial strains. In addition to these endogenous factors, external treatment conditions, such as light intensity, light dosage, availability of nutrients, temperature, and presence of exogenous photosensitizers, are known to contribute to the varying blue light inactivation profiles in clinical and foodborne bacteria [18][19][23,24]. Thus, the frontier of research in this area needs to be extended to include systematic determination of both inherent and external factors affecting the efficacy of antimicrobial blue light against different bacterial strains, with the subsequent establishment of accessible databases for improved predictability of bacterial tolerances or resistances.

*Authors: Joshua Hadi, Shuyan Wu, Aswathi Soni, Amanda Gardner, Gale Brightwell