Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Vicky Zhou and Version 1 by Antonio Sánchez-Bayón.

Green jobs, described as those jobs generated around sustainability and European Green Deal (EGD), have become “the emblem of this sustainable economy” according to the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) report. Studies on green economy and green tourism have increased substantially in the last decade, but it is also true that there is a lack of studies that determine what green job opportunities exist in the Spanish hotel sector under the umbrella of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and sustainability policies.

- political economy

- economic policies

- European Green Deal

- recovery plan

- green jobs

- wellbeing economics

- Tourist Sector

1. International Institutions Perspective on Sustainability and Green Jobs

At the beginning of the green deal, the international institutions had a very positive outlook regarding opportunities for decent and green jobs. As the green deal developed, some authorities and authors have started to be more cautious. After analyzing statistics of green jobs in the U.S. [1], Deschenes [2] concluded that the so-called green jobs represented a very small share of the employment in the U.S. and its growth has been weak in the 2010 decade.

Sustainable tourism has been a popular topic in research since the 1990s, both in international institutions and scholars [3][4][5]. UNWTO [6] defined sustainable tourism as the one that subscribes to SDGs and therefore supports the reduction of poverty, rural development, preservation of local cultures, encourages gender parity, protection of the environment and actions to mitigate climate change.

International institutions (i.e., European U, ILO,nion (EU), International Labour Organization (ILO), World Tourism Organization UNWTO(UNWTO)) have carried out studies on the impact and possibilities for tourism in the green economy. UNDP [7] concluded that, if tourism is not properly managed, “it might have a negative impact on people, planet, prosperity and peace” (in terms of Wellbeing Economics (WBE)). The role of tourism in sustainability is undeniable. UNWTO, UNEP and WMOWorld Meteorological Organization (WMO) reports mentioned in the same conference estimated that tourism alone accounts for 5% of global emissions. In a “business-as-usual” scenario for tourism and without a sustainable approach, 30-year projections show a 150% growth in emissions generated by the tourism industry [8].

The reports of the main international organizations coincide in pointing out that green tourism can bring broad economic, social and environmental benefits, although there are also many challenges and difficulties to overcome. In the same line, the UN Conference on Trade and Development [6] stated the potential of tourism to create jobs and facilitate sustainable development, especially considering that tourism is the main source of income for a third of the least developed economies on the planet [9]. It concluded that sustainable tourism is not a special type of tourism, but that all tourism must struggle to be more sustainable.

Since 2010, UNWTO has also stated the importance of sustainability in tourism and its positive impact on decent work. UNWTO 2030 Sustainable Development Goals Agenda mentions “the need to implement policies to promote sustainable tourism that creates jobs and supports local cultures and products” [10]. According to UNWTO [11], sustainable tourism must meet the triple objective of making optimal use of environmental resources: respect the authenticity of local communities, and ensure the long-term viability of its operations, providing economic benefit and employment opportunities in the communities where it operates and alleviating poverty. These three concepts—providing job opportunities, eliminating poverty and creating decent jobs—are aspects clearly associated with sustainable tourism and enable a wider scope of the possibilities of work linked to sustainability.

Following the previous statement, UNWTO [12] clearly connects sustainable tourism with decent jobs. The organization concluded that tourism has a very important impact on the World economy and job creation, especially for women, youths and immigrants. Additionally, its impact on rural and indigenous communities and their connections with other sectors of the economy is high. Sustainable tourism can and should reduce poverty and create decent jobs. This is especially relevant in tourism, traditionally characterized by monotonous and very demanding job, with high working hours, shifts and unattractive salaries.

One of the concepts that have generated more discussion in the literature has been precisely the exact definition of green job. The joint UNEP/ILO/IOE/ITUC report [13] defines a green job as any decent job that contributes to preserve and restore the quality of the environment, whether it be in agriculture, industry, services or administration, and it does so by reducing the consumption of energy and raw materials, minimizing pollution and waste, protecting and restoring ecosystems and allowing companies and communities to adapt to climate change [14]. They conclude that green jobs are any employed or self-employed job that clearly contributes to a more sustainable World.

Green jobs are often associated with the concept of decent work. The ILO (2013) concludes that both concepts should be worked together due to their link to the SDGs [15]. Regarding the exact definition of green jobs, ILO reports cite the most widely accepted definition. ILO started the Green Jobs Global Program in 2009 [16]. Jobs are considered green when they help reduce negative environmental impacts and help create socially, economically and environmentally sustainable businesses. Green jobs are all those jobs that contribute to creating a more sustainable World (remember the ILO update on the topic, connecting green jobs with other fields, like WBE, supporting the research of many scientists and scholars.

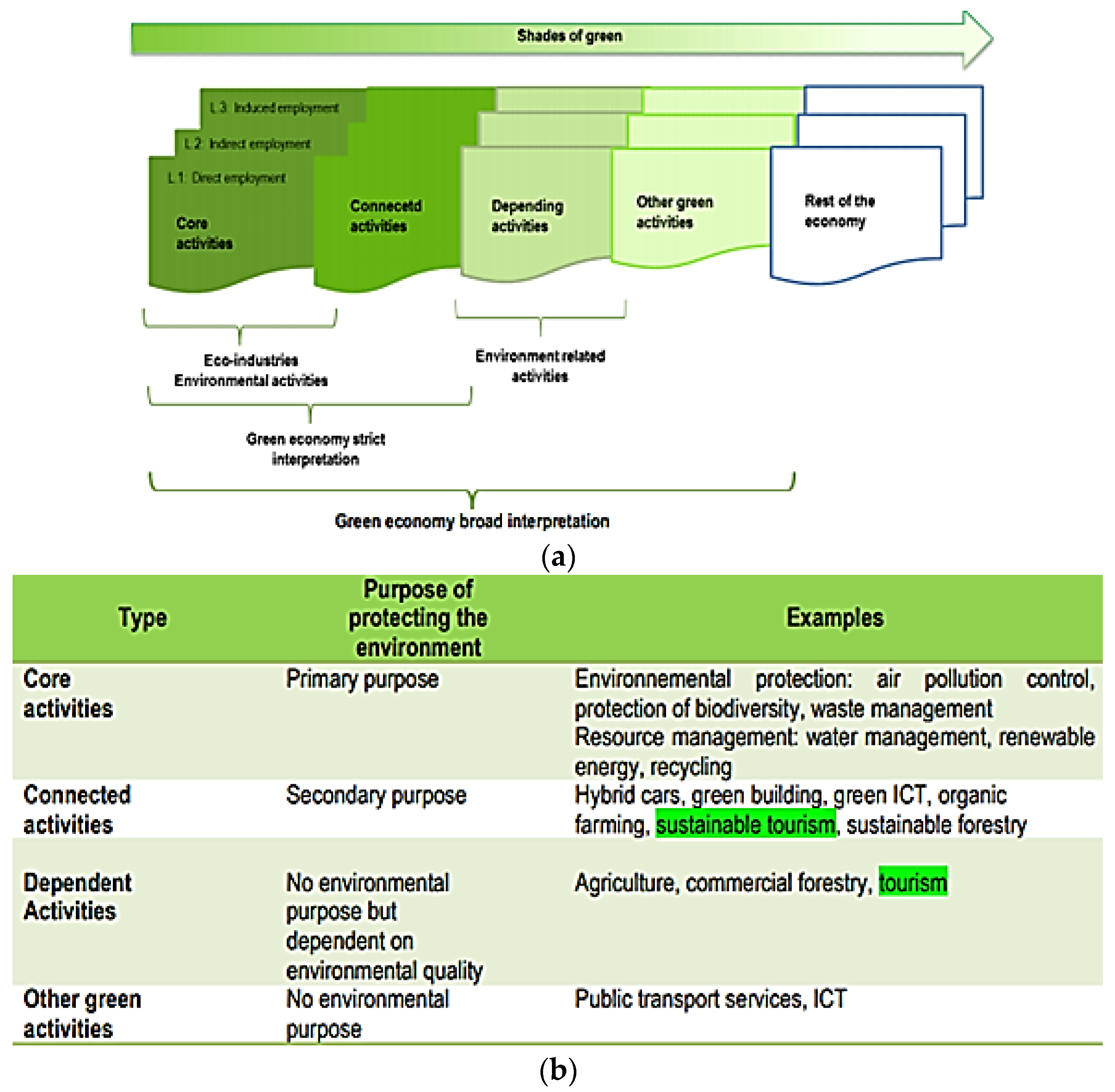

Following UNWTO [17], one of the main difficulties that studies on the impact of sustainability and green jobs on tourism must face is the absence of common lists of jobs for the green sector in most countries. This makes it very difficult to measure quality and quantity of green employment in tourism and the actual number of green jobs in the industry. There are no common job classifications to allow researchers to find green jobs in tourism. The conceptual framework of the green economy is suggested as the basis for measuring sustainable tourism, as can be seen in Figure 21a,b.

Figure 21. (a) Theoretical framework of green economy. (b) Characteristics of different types of green jobs. Source: UNWTO and IDEA Consultant [16][17].

Figure 21. (a) Theoretical framework of green economy. (b) Characteristics of different types of green jobs. Source: UNWTO and IDEA Consultant [16][17].

The primary activities are the most directly linked to sustainability (ecological, agricultural and environmental activities) and sustainable tourism would be included in the group of secondary connected activities or in the third level “dependent activities”( described as other non-sustainable tourist activities). The UNWTO report recognizes the difficulty of correctly discriminating between activities related to green tourism, given that the general data available in reports and censuses do not usually differentiate green jobs. Only a small group of countries have established metrics for green jobs in all sectors [18]. Conversely, in most countries the only jobs considered within the category of green jobs are those included in the basic list of positions and linked to recycling, waste management, environmental management and renewable energy [19].

By the same token, all job categories included in the first ILO list for green jobs are jobs in traditional sectors of the green economy (i.e., environmental conservation, recycling and renewable energy jobs, eco agriculture and farming, as well as environmental training and consulting). That green job list does not connect with a significant number of people at tourism companies. Beyond the teams and professionals who work in large tourism companies on EMSs and related issues: consulting, training, recycling and environmental certificates and audits the figures for green jobs in tourism are limited.

A primary source of research is precisely the categorization of green jobs within the tourism business. Ladkin and Szivas [20] mention the difficulty of determining what is and what is not a green job. As an example of the large gray area around the concept of green job, a study carried out by the government of Spain [21] asserts that the number of green jobs in Spain was 530,947 workers, equivalent to 2.6% of the Spanish workforce in 2009. The same report remarks that the total number of jobs in the green economy had doubled in a decade in Spain, becoming the average for the EU.

Nevertheless, the actual possibilities of an increase of green jobs in Spanish tourism companies are not easily identifiable. Based on these same data from Spain, the organization Green Jobs and Sustainable Development International Center (2013), also known as GJASD International, ends up concluding that, since tourism is so important in the Spanish economy, it is reasonable to think that a part of green jobs have probably been absorbed by the tourism industry [22], but this statement is only a deduction based on general data provided in a report by the Spanish Ministry of the Environment [23] and not cross-checked with other sources of data on green jobs in the Spanish tourism sector or any other further analysis.

Regarding the actual work opportunities for green jobs, when we review the different documents and employment estimates provided by the EU about employment growth linked to sustainability, the first conclusion is that figures and forecasts are very volatile throughout the years. In the case of the EU, the first statements (1997), related on sustainability and antecedent of EGD, declared that the green economy could create between 950,000 and 1,650,000 green jobs around green energies and sustainability. This very enthusiastic initial estimate has given way to more conservative data over the years. For example, in 2021, the EU estimated that renewable energies could create between 200,000 and 300,000 jobs by 2030, a much lower figure and which is only 12% from the previous data provided by EU authorities.

A report by Szako [24] concluded that there are possibilities for significant growth in job opportunities in the green economy, and as much as 87 million jobs susceptible of been “greeneable”. This does not necessarily mean the creation of new jobs, but the adaptation that many current jobs, mostly in the energy sector, will experience in their way towards a greener economy. Bowen et al. [25] describe a taxonomy with the changes that green jobs could bring. There will be: (1) Existing jobs whose demand will increase in the green economy, (2) existing jobs that will change substantially in tasks, skills and knowledge requiring great re-skilling, (3) emerging new jobs brought up by the demand of the green economy, (4) rival non-green jobs similar to green jobs in different sector, and (5) non-green jobs not very likely to be substantially affected by the green economy. The authors do not mention green jobs for tourism, but they assert that there is potential growth of green jobs in tourism linked to the investments in sustainable tourism. Following the mentioned taxonomy, tourism seems to fit better in the fifth group, that is, non-green jobs not very likely to be affected by the green economy.

The ILO [26] report on opportunities for green jobs mentions Spanish tourism as one of the “areas of opportunities” for the growth of green jobs, given the importance that tourism has for the Spanish economy and the initial impulse of Spanish government towards renewable energies.

The structure of the Spanish labor market is complex, with many more skilled workers than the EU average, but also a higher percentage of unskilled workers than the EU average and far fewer medium-skilled workers compared to the EU, which is interpreted as a difficulty at the time to successfully fill the green jobs, which mostly need medium-skilled workers [27][28].

Beyond the initial assessment on tourism and green jobs, ILO report does not make further analysis about the possibilities of green jobs in tourism and hospitality. In its report Green Skills for Green Jobs [29], ILO recommends increasing training in green skills in both job search workers and already employed workers, in the first ones to increase their job opportunities and in the second ones to maintain a high level of employability, because green skills will be important to maintain professional skills and will need to be updated. The report pauses briefly on the tourism sector to mention that people working at tourism will need more training and re-skilling in new knowledges and skills in environmental aspects, especially in topics such as ecotourism, bio tourism and circular tourism and energy management systems, but opportunities for green jobs are not mentioned. Tourism will need skilling and re-skilling on green topics, but not an increase in new and specific green jobs.

Regarding green jobs in the tourism sector in Spain, Sánchez and Poschen [30], in their technical note for ILO, initially estimated that only renewable energies could generate 20 million jobs throughout the EU. Several years later, the report sponsored by the Government of Spain Green Employment in a Sustainable Economy [31] concluded that the sustainable economy could allow Spain to create 1,153,000 total green jobs. The same study estimates that the green economy could create up to 24,000 new jobs in Spanish tourism, a very humble figure, especially when compared to the total green jobs forecasted for Spain.

According to a study by the Biodiversity Foundation sponsored by the Spanish Ministry of Environment [19], one of the most important conditions for governments to decide to promote policies and actions related to sustainability largely depends on the impact of these measures on employment. According to the same study, almost 4.5 million people (full-time equivalent-FTE) in the EU worked in the green economy in 2016, 1.4 million more than fifteen years ago. However, overall employment estimates provided by the 2009 Spanish study, later mentioned by ILO, does not coincide with the recent data issued by the EU regarding green jobs. In the case of Spain, after the shift in the Spanish legislation about renewables energies in 2015, cutting back subventions to those energies, estimation for new green jobs fell down to 46,534 direct jobs and 29,121 indirect jobs in 2015, a very modest figure when compared with 2009 predictions of about 530,947 green jobs.

2. Sustainable Tourism and Green Jobs

Sustainable tourism has had broad resonance in tourism research, being perceived as an opportunity to address new issues beyond the negative impacts of the activity, which were present in the literature in previous decades of research [32]. Buckley [33] estimates that more than 5000 papers on sustainable tourism have been published in the last 25 years, confirming the great interest of scholars in sustainability and its implications. Hall [5] considers that the relationship between tourism and the environment has become increasingly problematic as it is accepted that tourism leads to a degradation of natural resources in both the short and long term. The author asserts that tourism is essentially about renting a place in another country or another location for a given agreed time, so the risk for the environment in those rented locations can be high if it is not controlled. Torres-Delgado and Palomeque [34] analyze the policies and studies on sustainability carried out up to that year. His first conclusion is that the proliferation of documents in sustainable tourism has not led to a proportional advance either in theoretical or practical aspects of this concept. Sustainability in tourism research has been first associated with environmental aspects to progress later towards more holistic approaches, seeing sustainability as a tool for economic development, wellbeing and preservation of the environment. The authors also concluded that research on sustainable tourism has more interest in the environment and less in social and economic aspects. Branwell and Lane [35] agree that research on sustainability in tourism has been important in the academic world and has become increasingly robust and varied thanks to the support of public sectors, national research councils and the private sector that they have provided. funds to support research in sustainable tourism. Other authors are still critical of the prevailing trends in tourism research and sustainability, defined by Hall [5] as neoliberal. After reviewing the studies on tourism and sustainability, this author laments the paucity of research on the true contribution of tourism to sustainability, all at a time when tourism seems less sustainable than ever. However, studies on green jobs are still scarce. Regarding academic research on sustainable tourism and its impact on employment, it is important to highlight that there is no consensus among the different authors regarding the positive impact on the labor market of sustainability policies. The work of Álvarez et al [36] is skeptical with respect to the real possibilities of the green economy to create employment without destroying it in other sectors of activity. According to the author, following the first EU announcements about employment opportunities in green jobs in 1997, many voices rose above the general euphoria to point out that sustainability policies might create jobs in the green economy, especially renewable energies, but it will also destroy jobs in other sectors, due to the loss of competitiveness in other businesses due to the higher cost of renewable energies and the transfer of funds to that green energies in detriment of other areas of the country economy. Thus, each megawatt obtained through renewable sources destroys an average of 5.05 jobs, given the high cost of generating that green energy and the risk of company’s closures and relocations. In other words, the jobs created by sustainable energies are created by destroying jobs in other sectors. A study by Sulich and Rutkowska [37], on green job opportunities for young people in three European countries (Poland, Belgium and the Czech Republic), concluded that more than 15% of new youth jobs in Poland and Belgium were green jobs. However, the proportion was much lower in the Czech Republic, where only 2% of job offers for young people came from the green economy. Opportunities in the green economy are unequal depending on each country, its productive sectors and the available workforce. Research on sustainability in tourism has enjoyed a boom in recent years and the number of articles and papers has grown dramatically. Niñerola et al. [3] confirm that the number of publications on the subject has reached publications. There is a growing interest both in sustainability in tourism and in all related concepts: circular tourism, blue tourism, blue tourism, bio tourism and ecological tourism. However, few studies have focused on the impact of measures related to sustainability on human resources and the impact of employment in tourism industries. A good share of studies focuses on the different concepts of sustainable tourism and their implications. Ruhanen et al. [4] confirm that sustainability is a topic of extraordinary interest. However, the specific topic of decent work and sustainability in the tourism sector is still low in studies. Bianchi and DeMan [38] point out that the vision of legislators and governments on tourism work is in many cases superficial, concentrating above all on the possibilities of a constantly growing sector and less on aspects of justice and work equity at tourism companies. This transformation of the sector is necessary. Additionally, and because of the changes brought back by digital transition and its impact in the business culture, the hotels and their employees cannot be more focused on quality of service. The reconversion of the sector has to deal with the first step of the digital economy—the gig economy—which includes the collaborative and circular economy, the autonomous economy and the orange economy. The next step of the digital economy is WBE: The new green jobs (according to the Ricardo’s effect or readjustment) have to attend to an industry of emotions and experiences; so it is necessary to connect with talent-collaborators, who are more productive, and they keep the sustainable 3P relation in a motivational way (not as a coercive issue, better as a win–win game with higher satisfaction and wellbeing for everyone [39][40][41][42][38][43][44].References

- US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Measuring Green Jobs. Available online: https://www.bls.gov/green/home.htm (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Deschenes, O. Green Jobs (No. 62); IZA Institute of Labor Economics: Bonn, Germany, 2013.

- Niñerola, A.; Sánchez-Rebull, M.V.; Hernández-Lara, A.B. Tourism research on sustainability: A bibliometric analysis. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1377.

- Ruhanen, L.; Weiler, B.; Moyle, B.D.; McLennan, C.L.J. Trends and patterns in sustainable tourism research: A 25-year bibliometric analysis. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 517–535.

- Hall, C.M. Constructing sustainable tourism development: The 2030 agenda and the managerial ecology of sustainable tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1044–1060.

- UNWTO. Sustainable Development of Tourism. 2012. Available online: http://sdt.unwto.org/en/content/about-us-5 (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- UNDP. Annual Report 2017. Available online: https://annualreport.undp.org/2017 (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Valero-Matas, J.A. El espejismo de una energía social. La economía del hidrógeno. Rev. Int. Sociol. 2010, 68, 429–452.

- UNDP. Making Tourism More Sustainable. A Guide for Policy Makers; United Nations Environment Programme and World Tourism Organization: Madrid, Spain, 2015.

- UNSD. UN Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/ (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- UNCTAD. The Contribution of Tourism to Trade and Development; TD/B/C.I/8; UNCTAD: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010.

- UNWTO. 6th International Conference in Tourism Statistics Measuring for Sustainable Tourism. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/archive/asia/event/6th-international-conference-tourism-statistics-measuring-sustainable-tourism (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- ILO. Sustainable Development, Decent Work and Green Jobs. Report V. International Labour Conference. 102nd Session, Geneva. 2013. Available online: http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/@ed_norm/@relconf/documents/meetingdocument/wcms_207370.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- ILO. Green Jobs Programme of the ILO. Available online: http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_emp/---emp_ent/documents/publication/wcms_371396.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Poschen, P. Decent Work, Green Jobs and the Sustainable Economy: Solutions for Climate Change and Sustainable Development; Routledge: London, UK, 2017.

- ILO. ILO Green Jobs. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/green-jobs/WCMS_213842/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Chernyshev, I. Employment, Green Jobs and Sustainable Tourism. Available online: http://webunwto.s3.amazonaws.com/imported_images/48535/chernyshev_conf2017manila_central_paper.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Bilsen, V. Green Jobs. Final Report. IDEA Consult in Collaboration with RDC Environment (3E). Brussels, May 2010. Available online: file:///D:/downloads/Final%20report%20green%20jobs%20IDEA.pd (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Valero-Matas, J.A.; De la Barrera, A. The Autonomous Car: A better future? Sociol. Techscience 2020, 10, 136–158.

- Ladkin, A.; Szivas, E. Green jobs and employment in tourism. In Tourism in the Green Economy; Routledge: London, UK, 2015.

- Spanish Ministry of Enveronment. Empleo verde en una Economía Sostenible. Available online: http://www.upv.es/contenidos/CAMUNISO/info/U0637188.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- Jugault, V. Green Jobs for Sustainable Tourism. Available online: https://webunwto.s3-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/imported_images/45423/gjasd_international.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- European Commission. Renewable Energy in Europe. 2020. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/news/focus-renewable-energy-europe-2020-mar-18_en (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Szako, V. Employment in the Energy Sector; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2020.

- Bowen, A.; Kuralbayeva, K.; Tipoe, E.L. Characterising green employment: The impacts of ‘greening’on workforce composition. Energy Econ. 2018, 72, 263–275.

- ILO. Green Jobs for Sustainable Development, a Case Study for Spain. 2012. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_emp/--emp_ent/documents/publication/wcms_186715.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- European Commission. Eures: Short Overview of the Labour Market. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eures/main.jsp?catId=2627&countryId=ES&acro=lmi&lang=en (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- European Commission. Labour Markets. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/3217494/5734929/KS-HA-12-001-05-EN.PDF.pdf/f60b7339-a767-4400-8036-1d6294913a23?t=1414776599000 (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- ILO. Green Skills for Green Jobs. 2011. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/global/publications/ilo-bookstore/order-online/books/WCMS_159585/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Sanchez, A.B.; Poschen, P. The Social and Decent Work Dimensions of a New Agreement on Climate Change. 2010. Available online: https://www.uncclearn.org/wp-content/uploads/library/ilo22.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Spanish Government. Informe Sobre Empleo Verde. Available online: https://www.empleaverde.es/sites/default/files/informe_empleo_verde.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Bramwell, B.; Lane, B. Towards innovation in sustainable tourism research? J. Sustain. Tour. 2012, 20, 1–7.

- Buckley, R. Sustainable tourism: Research and reality. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 528–546.

- Torres-Delgado, A.; Palomeque, F.L. The growth and spread of the concept of sustainable tourism: The contribution of institutional initiatives to tourism policy. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2012, 4, 1–10.

- Branwell, B.; Lane, B. What drives research on sustainable tourism? J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 1–3.

- Álvarez, G.C.; Jara, R.M.; Julián, J.R.R.; Bielsa, J.I.G. Study of the effects on employement of public aid to renewable energy sources. Procesos de Mercado: Revista Europea de Economía Política 2010, 7, 13–70.

- Sulich, A.; Rutkowska, M. Green jobs, definitional issues, and the employment of young people: An analysis of three European Union countries. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 262, 110314.

- Bianchi, R.V.; de Man, F. Tourism Inclusive growth and decent work: A political economy critique. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 1–19.

- Trincado, E.; Sánchez-Bayón, A.; Vindel, J.M. The European Union Green Deal: Clean Energy Wellbeing Opportunities and the Risk of the Jevons Paradox. Energies 2021, 14, 4148.

- García Vaquero, M.; Sánchez-Bayón, A.; Lominchar, J. European Green Deal and Recovery Plan: Green Jobs, Skills and Wellbeing Economics in Spain. Energies 2021, 14, 4145.

- Sánchez-Bayón, A.; García-Vaquero, M.; Lominchar, J. Wellbeing Economics: Beyond the Labour compliance & challenge for business culture. J. Leg. Ethical Regul. Issues 2021, 24, 1–15.

- Sánchez-Bayón, A.; Trincado, E. Business and labour culture changes in digital paradigm. Cogito 2020, 12, 225–243.

- Ayuso, S. Adoption of voluntary environmental tools for sustainable tourism: Analysing the experience of Spanish hotels. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2006, 13, 207–220.

- Sánchez-Bayón, A.; Lominchar, J. Labour relations development and changes in digital economy. J. Leg. Ethical Regul. Issues 2020, 23, 1–13.

More