Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Diogo Rato and Version 2 by Vicky Zhou.

Socio-cognitive agents should be able to support an agent’s reasoning about other social actors and its relationship with them. Cognitive social frames can be built around social groups, and form the basis for social group dynamics mechanisms and construct of social identity.

- agent-based modeling

- socio-cognitive systems

- social agents

- social identity

1. Design Principles of the New Socio-Cognitive Agents

Despite the increasing presence of autonomous agents in people’s daily lives, several researchers have highlighted the importance of understanding the social world in each individual’s cognition. This connection and its implications have been a research topic that has called the attention of multiple theorists that study this phenomenon, and computer scientists that recognize its importance in the design of intelligent agents. In the late 1990s, Castelfranchi argued that intelligence is a social phenomenon and that, in artificial intelligence, researchers construct socially intelligent systems to understand it [1]. However, more recently, AI’s goal regarding social intelligence has shifted towards designing and developing social agents that live alongside humans in a socially adequate manner. Nevertheless, the need to create social agents should not promote the inclusion of modules of social behavior as additions to the agent’s cognition [2]. Instead, an agent’s social nature should spread through its cognition.

To guide the design of socio-cognitive agents, five design principles are elaborated that should be taken into account.

12.1. Socially Situated Cognition

Human actions are influenced by external factors. From characteristics of the environment that restrict physical capabilities, to the presence of others that demand an adaptation of the speech tone; for example, people adapt their behavior to the situation they are placed in. Clancey proposed the notion of situated cognition to explain the process people use to adapt their cognition based on their surroundings [3]. His proposal states that “all processes of behaving, including speech, problem-solving, and physical skills, are generated on the spot [.]”. Primarily motivated to describe how knowledge is constructed in human’s minds, the author suggested that people’s cognitive resources are deployed as required by the context. In Clancey’s proposal, knowledge is described as inherently social, similar to human actions, defining human’s activity as socially oriented, as well as socially shaped [4]. Similarly, Suchman also argued that not only physical but also social context can guide, restrict, or even fully decide people’s actions [5].

To study situated cognition in a social context, Smith and Semin introduced the concept of socially situated cognition [6]. It proposes four different properties of cognition: cognition is for action, cognition is embodied, cognition is situated, and cognition is distributed. The authors extensively reviewed evidence that situated action enables the appearance of social cognition. For instance, Schwarz argues that the perceivers’ perspective of the context strengthens the sensitivity to external artefacts during attitude construal [7].

Socially situated cognition is considered as one of the most important design principles to endow social agents with the capability to selectively deploy their cognitive resources as the social environment requires. Although generating cognitive resources on the spot is not suitable for computational models, as Clancey proposed, its capabilities should evolve with the agent’s experience. Moreover, the sensitivity to the social context promotes the recruitment of only a part of the cognition that is deemed necessary, reducing the computational load on complex systems.

Socio-cognitive agents must be able to understand the situation (e.g., the adequate social roles and norms, and the relationship of the social actors) and act accordingly, but without losing the agency to choose whether to adhere to social pressures that the situation upholds. In contrast to normative systems that restrict agents’ actions to avoid a chaotic social world, socio-cognitive agents should not be enforced to blindly change their behavior by an outside source. The agent’s cognition should be the one promoting the balance between external pressures, such as social norms, and personal preferences. Overall, the principle can be summarized as:

A socio-cognitive agent must selectively deploy its cognitive resources, hence adapting its behavior, according to the social context.1.2. Social Context and Construal

2.2. Social Context and Construal

From the objects available around people to their relationships with other social actors, the entities that surround people have a direct influence on their cognitive processes. Nevertheless, not all humans ascribe similar meanings to the same entities they see in the physical world. In addition to the sensory experience that generates a perception, people construct mental representations of the world that are subject to an interpretative process.12.3. Social Categorization and Identity

Allport studied human’s natural process for thinking about others in terms of their group memberships by means of social categorization [12]. As part of their social nature, people tend to categorize other social actors on the basis of their social groups’ memberships. Therefore, being able to recognize others’ social groups, a person can also identify himself based on his relationship to such groups. This interaction between one’s identity as a group member and the inter-group’s dynamics was elaborated by social identity theory [13]. It proposes that people are capable of constructing their social identity based on their relationship with other social groups. Later, Adams and Hoggs predicted that social identities can be taken as required by the situation, the social context [14]. Together, both formulations suggest that humans can assume an identity as they see fit while being capable of recognizing, and comparing to others’ memberships. Brewer further elaborated on the inter-group behavior, by proposing that one, when adopting a social identity, balances the similarities with other in-group members and the distinction between in-group and out-group [15] members.12.4. Social Affordances

According to Gibson, affordances are the interactive opportunities offered by the environment to an organism [17]. For instance, a book can afford several types of interactions ranging from interactions that are more common, such as, opening the book or reading its paragraphs, to other less orthodox interactions, such as using it as a cup holder or a wobbly table’s stabilizer. However, an affordance does not live inside the organism nor the environment; it emerges from the ecological relationship between both parties [18]. Moreover, affordances result from the coupling of perceptual information with the organism’s cognitive capabilities. Since Gibson’s theory of affordances was mainly conceived for direct visual perception, his proposal did not detail the role of cognition on the conception of affordances. Nevertheless, Gibson briefly challenged the affordances’ original domain, alluding that other biological perceptions or cultural processes may allow the emergence of other types of affordances. In the past four decades, following his initial contributions, other researchers extended the original theory and explored the cognition’s implications in recognition of affordances.12.5. Socially Affordable

Alongside its ecological motivation, social affordances can also bring technical improvements for social agents. Gibson argued that perception is not about passively constructing an internal representation of the world, but rather about actively picking up information of interest to one’s behavior [18]. As such, an agent that only perceives information that is worth considering reduces its set of relevant perceptions. Computationally, it means creating an attention process that allows an agent to filter the perceptions based on their relevancy to its cognition. Nevertheless, this approach may not be sufficient to create agents that are more socially capable. Being able to recognize social affordances, opportunities for interaction with other social actors in the environment, does not necessarily mean that those potential interactions are adequate for the social context. Instead, understanding the distinction between what is possible, the mentioned affordances, and what is appropriate, hence, socially affordable, endows agents with the capability to adhere to social conformity.

2. Cognitive Social Frames for the New Socio-Cognitive Agents

Humans live alongside other social actors. As members of society, people need to adapt actions to fit others’ expectations. Similarly, social agents must change their behavior according to their reality. To endow this capability to socio-cognitive agents, from virtual agents to robots, scientists must develop mechanisms to adapt their cognition based on their interpretation of the physical reality. A cognitive social frame (CSF) is the core element of a framework that enables the adjustment of the agent’s cognition based on its interpretation of the surroundings. The latter is an internal representation of the agent’s relationship with the things and other social actors placed in the world. This mental representation is called social context. The agent’s cognition is encapsulated into several abstract blocks called cognitive resources. They contain specific knowledge and mechanisms used to determine the agent’s actions. Finally, each CSF establishes a link between the social context and the relevant cognitive resources, that will be used to determine which cognitive resources should be deployed.2.1. Architecture

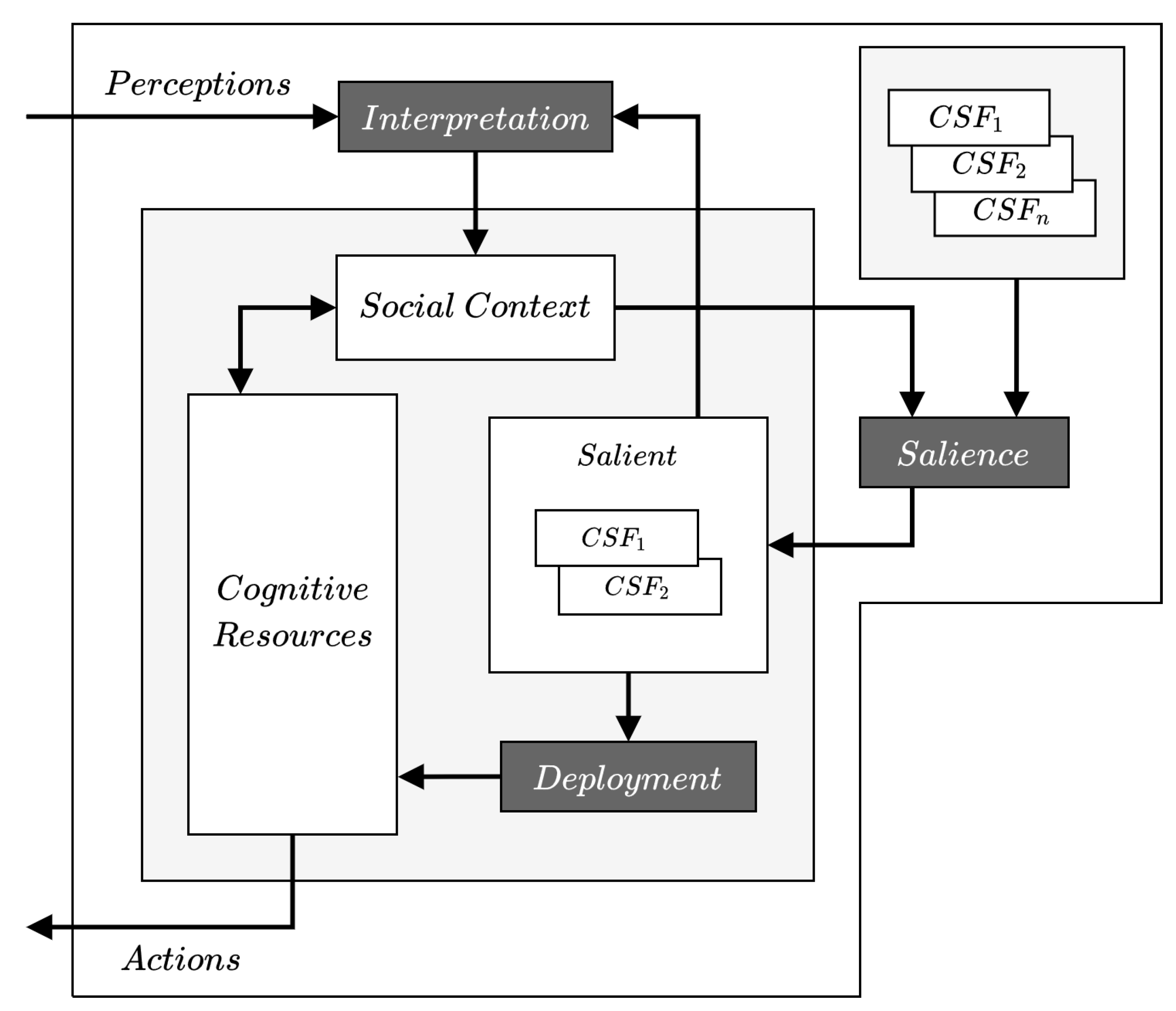

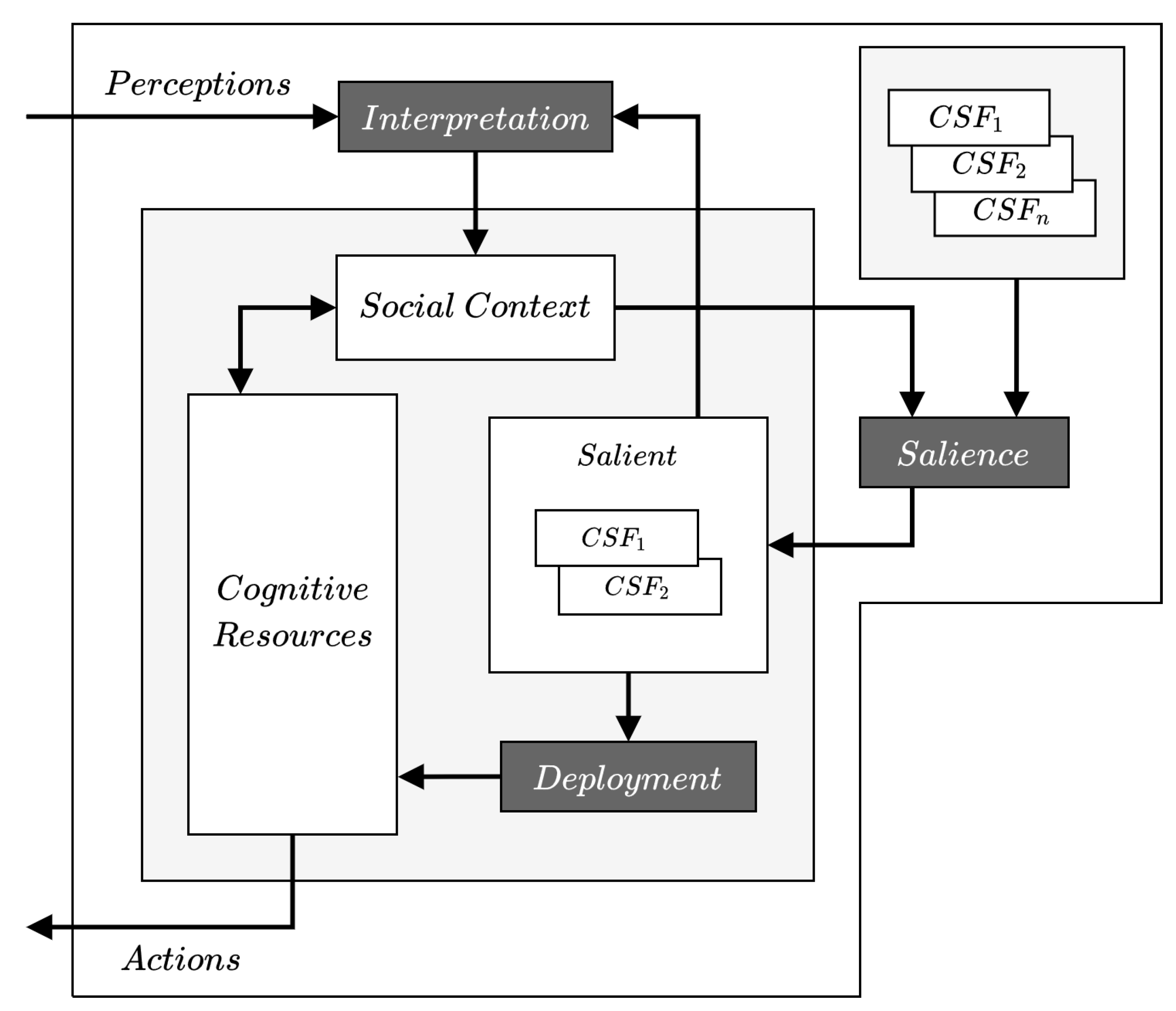

Throughout its interactions with the environment, the agent will receive new perceptions and interpret them. This process results in new social contexts that will guide the adjustment of the agent’s cognition. The connection between the social context and the agent’s cognition is represented by the concept of cognitive social frame. Although the agent holds a collection of possible CSFs, at a certain moment, only a subset of those is considered appropriate for the social context, called salient cognitive social frames. Each CSF identifies the proper cognitive resources to deploy when it is salient. The architecture does not impose limitations regarding the internal processes of each cognitive resource. However, some restrictions regarding the knowledge accessibility are established. Figure 1 provides a high-level view of the interaction of the cognitive social frames with the remaining concepts of the model. The following sections elaborate on each concept and how they contribute to the agent’s loop.

Figure 1. Cognitive social frame’s architecture illustrating the interaction of the model’s components highlighting the three main stages of the agent’s mechanism: Interpretation—the perceptions are interpreted based on the salient cognitive social frames to form the social context, Salience—all cognitive social frames assess their salience based on the social context, and Deployment—the salient cognitive social frames update the set of active cognitive resources.

The proposed computational model’s goal is to enable the creation of socio-cognitive agents that have the capability to adapt their cognition according to the social context, i.e., their interpretation of the social world. The model fulfils this goal, by introducing a mechanism based on the concept of cognitive social frame, which work as the link between the agent’s social context and its cognition.

Aligned with the design principle of socially situated cognition, the main motivation of cognitive social frames is to establish a link between the agent’s situation, formally represented in the social context and its cognition, encapsulated in its cognitive resources. As such, the agent is sensitive to the view of the surrounding world when deploying its cognitive resources. However, it is important to note that this sensitivity to the social context should not be confused with dependency. Although the agent takes into account the social context, using the model, its cognition’s deployment is also influenced by its own preferences.

A socio-cognitive agent implementing the mechanism can interpret the world, as stated in the social context and construal principle, rather than just perceiving it. The second stage of the mechanism allows a socio-cognitive agent to construct a mental representation, the social context, describing its relationship with perceived elements. This social context is the set of social perceptions that result from the application of each salient cognitive social frame construal function. This function is responsible for filtering the agent’s perceptions and then applying a social layer on top of them. As such, the social context enables the observer to allow its cognition to reason about the meaning of the elements of the physical world instead of the elements by themselves.

Additionally, in the interpretation phase, the agent can construct a social context. This process is also influenced by the salient cognitive social frames. Therefore, the interpretation of the reality is performed from the agent’s frame of reference with regard to its relevance to the agent’s cognition. As stated in the social affordances principle, a socio-cognitive agent should perceive what is worth paying attention to and identify social interaction opportunities in the social context. The proposal supports this suggestion since it only applies the construal function of the salient CSFs relevant for the cognition, to create the social context. A socio-cognitive agent should recognize what is socially affordable. In line with this remark, a cognitive social frame represents the cognitive resources that are associated with a particular social context and, to a certain degree, it also dictates how the agent can interact with the world. Moreover, while building the social context, CSFs are attributed to other social actors as well. This supports the identification of social affordances, but at the same time is a mechanism that enables certain mind-reading capabilities in the agent.

Finally, one of the most promising aspects of the proposal is related to the principle of social categorization and identity. The concept of cognitive social frames supports the appearance of the concept of social identity by enabling a socio-cognitive agent to identify its and others’ social categories. When placed in a world with other social actors, an agent capable of representing the concept of CSF can also assign to others their salient CSFs. Furthermore, it can also reason about its beliefs regarding others’ salient CSF and their social categories. However, this principle also claims that not only should a socio-cognitive agent recognize others’ group memberships but also be able to construct its own social identity based on its relationship with the social category, by defining personal preferences over some identities. Regarding the first, a cognitive social frame can be used as the concept that enables the categorization of social actors and, therefore, defines groups of social actors that share similar CSFs. With interest to the second, the mechanism allows the cognitive resources to reason about the concept of cognitive social frames and project into others’ salient CSFs, modeling others’ categories. With this information, an agent can explore its relationship with other social actors, considering their memberships, towards defining its own social identity.

In addition, by considering the salient CSFs of other social actors with its own cognition, an agent is capable of reasoning about others’ deployed cognitive resources and, therefore, acknowledge their beliefs, goals, mechanisms, and others. This mind-reading capability can enhance the social dimension of such agents since they can now expect and predict others’ actions based on their salient cognitive social frames. Furthermore, this mind-reading capability can be extended from the recognition of what cognitive resources are deployed to how another social actor interprets the physical world, thus creating social contexts from other frames of reference. Combining the two, the social context and cognitive social frames, a socio-cognitive agent has, to an extent, a mind-reading mechanism that allows it to understand the world from others’ perspectives and potentially anticipate others’ behaviors.

The ability to mind-read other social actors can help an agent establish relationships with other social actors. Instead of looking at the environment as a mere collection of opportunities for interaction, focusing on the interpersonal relationship with others creates agents that are more socially capable. When interacting with other social actors, an agent has a better chance of successfully engaging with them if it is aware of their drives, beliefs, norms, and other aspects that can be derived from their salient cognitive social frames. With this information, when interacting with other social actors, a socio-cognitive agent can search for common grounds with its interlocutors, thus strengthening their interpersonal relationship. CSFs can be used to explore the discrete (based on categories) nature of social relationships that are often treated as a continuous variable in multi-agent systems. For example, a CSF can be defined for friends and another for acquaintances and define in each the social norms that apply when the agent meets other actors that fit the CSF.

Additionally, agents with mind-reading capabilities can use their knowledge about others’ interpretation of the reality to manipulate the constructing of their social context, in particular, the identity (e.g., salient CSF) that others ascribe to the agent. Managing others’ impressions about itself requires a socio-cognitive agent to reason about others’ construction of the social context. Looking forward to inducing perceptions that will influence other’s views about itself, an agent can either adjust the information exchanged with others or modify the environment such that their construction of the social context alters the other’s interpretation of the social reality.

Finally, models for emotions and affect have also been researched towards creating better socio-cognitive agents. Indeed, considering that the goal is to create better human-agent interactions, emotional responses should also be focused when deploying such agents. However, the model does not enforce a specific emotional appraisal approach. Instead, the contribution focuses on identifying the adequacy of a behavior to the interpretation of the surrounding environment. Nonetheless, the inclusion of emotional appraisal mechanisms as cognitive resources can contribute to the identification of affordable emotional responses based on the social context.

References

- Castelfranchi, C. Modelling social action for AI agents. Artif. Intell. 1998, 103, 157–182.

- Dignum, F.; Prada, R.; Hofstede, G.J. From autistic to social agents. In Proceedings of the 2014 international conference on Autonomous agents and multi-agent systems. International Foundation for Autonomous Agents and Multiagent Systems, Paris, France, 5–9 May 2014; pp. 1161–1164.

- Clancey, W.J. Situated cognition: Stepping out of representational flatland. AI Commun. Eur. J. Artif. Intell. 1991, 4, 109–112.

- Clancey, W.J. The conceptual nature of knowledge, situations, and activity. In Human and Machine Expertise in Context; AAAI Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1997; pp. 247–291.

- Suchman, L.A. Plans and Situated Actions: The Problem of Human-Machine Communication; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1987.

- Smith, E.R.; Semin, G.R. Socially Situated Cognition: Cognition in its Social Context. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2004; Volume 36, pp. 53–117.

- Schwarz, N. Attitude construction: Evaluation in context. Soc. Cogn. 2007, 25, 638–656.

- Blumer, H. Symbolic Interactionism: Perspective and Method; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1986.

- Castelfranchi, C. Guarantees for autonomy in cognitive agent architecture. In International Workshop on Agent Theories, Architectures, and Languages; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1994; pp. 56–70.

- Dautenhahn, K. The art of designing socially intelligent agents: Science, fiction, and the human in the loop. Appl. Artif. Intell. 1998, 12, 573–617.

- Fong, T.; Nourbakhsh, I.; Dautenhahn, K. A survey of socially interactive robots. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2003, 42, 143–166.

- Allport, G.W.; Clark, K.; Pettigrew, T. The Nature of Prejudice; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1954.

- Tajfel, H. Human Groups and Social Categories: Studies in Social Psychology/Henri Tajfel; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1981.

- Abrams, D.; Hogg, M.A. Social Identity and Social Cognition; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1999; pp. 197–229.

- Brewer, M.B. Ingroup identification and intergroup conflict. Soc. Identity Intergroup Confl. Confl. Reduct. 2001, 3, 17–41.

- Owens, T.J.; Robinson, D.T.; Smith-Lovin, L. Three faces of identity. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2010, 36.

- Gibson, J.J. The theory of affordances. In Perceiving, Acting, and Knowing; Shaw, R., Bransford, J., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1977; pp. 67–82.

- Gibson, J.J. The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception; Houghton Mifflin: Boston, MA, USA, 1979.

- Riesenhuber, M.; Poggio, T. Neural mechanisms of object recognition. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2002, 12, 162–168.

- Cisek, P.; Kalaska, J.F. Neural mechanisms for interacting with a world full of action choices. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2010, 33, 269–298.

- Hirsh, J.B.; Mar, R.A.; Peterson, J.B. Psychological entropy: A framework for understanding uncertainty-related anxiety. Psychol. Rev. 2012, 119, 304.

- Kaufmann, L.; Clément, F. How culture comes to mind: From social affordances to cultural analogies. Intellectica 2007, 46, 221–250.

- Zhang, J.; Patel, V.L. Distributed cognition, representation, and affordance. Pragmat. Cogn. 2006, 14, 333–341.

- Kreijns, K.; Kirschner, P.A. The social affordances of computer-supported collaborative learning environments. In Proceedings of the 31st Annual Frontiers in Education Conference. Impact on Engineering and Science Education, Reno, NV, USA, 10–13 October 2001.

- Min, H.; Yi, C.; Luo, R.; Zhu, J.; Bi, S. Affordance research in developmental robotics: A survey. IEEE Trans. Cogn. Dev. Syst. 2016, 8, 237–255.

- Wiltshire, T.J.; Warta, S.F.; Barber, D.; Fiore, S.M. Enabling robotic social intelligence by engineering human social-cognitive mechanisms. Cogn. Syst. Res. 2017, 43, 190–207.

- Pandey, A.K.; Alami, R. Visuo-spatial ability, effort and affordance analyses: Towards building blocks for robot’s complex socio-cognitive behaviors. In Proceedings of the Workshops at the Twenty-Sixth AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Toronto, ON, Canada, 22–26 July 2012.

- Uyanik, K.F.; Calskan, Y.; Bozcuoglu, A.K.; Yuruten, O.; Kalkan, S.; Sahin, E. Learning social affordances and using them for planning. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society, Berlin, Germany, 31 July–3 August 2013; Volume 35.

- Shu, T.; Gao, X.; Ryoo, M.S.; Zhu, S.C. Learning social affordance grammar from videos: Transferring human interactions to human-robot interactions. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1703.00503.

More