Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Viera Horvathova Kajabova and Version 2 by Rita Xu.

Uveal melanoma (UM), a rare form of melanoma, is the most common intraocular cancer in adults.

- uveal melanoma

- KIT

- MLPA

- Monosomy 3

- protein expression

1. Introduction

Uveal melanoma (UM), a rare form of melanoma, is the most common intraocular cancer in adults [1]. It arises from melanocytes along the uveal tract, including the iris, ciliary body, and most often the choroid [2]. Almost half of UM patients develop metastases, which may be caused by a virtually undetectable neoplasm already present at the time of the primary tumor diagnosis [3]. UM spreads through the blood, with the liver being the preferred metastatic site, followed by the lungs and bones [4]. Due to the lack of effective therapies, outcomes for patients with metastatic disease remain dismal [5]. Risk of metastatic spread can be predicted through assessment of specific chromosome copy number alterations [6], gene expression profiles [7], and the mutation status of known UM driver genes [8].

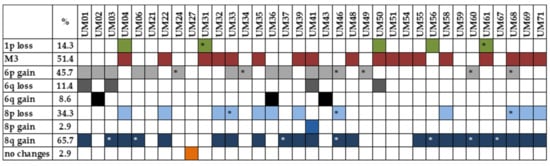

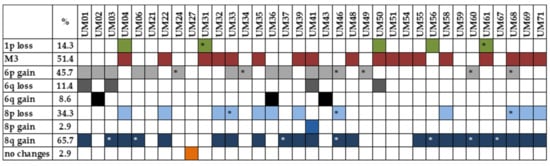

The correlation between UM prognosis and particular chromosomal rearrangements was noted long ago [9]. The most frequent UM-specific aberrations include monosomy of chromosome 3 (M3), a gain in the short arm of chromosome 6 (6p), or a gain in the long arm of chromosome 8 (8q). The combination of M3 and polysomy 8q poses a high metastatic risk and presents a poor prognosis, similarly to the loss of the short arm of chromosome 8 (8p), the long arm of chromosome 6 (6q), and the short arm of chromosome 1 (1p) [10][11][12][10,11,12]. Conversely, the presence of 6p amplification represents a protective factor due to its association with a good prognosis and lowered metastatic risk [13]. Another way to predict the risk of metastasis is via gene expression analysis. A prospectively validated, commercially available 15-gene expression panel developed by Castle Biosciences categorizes patients as Class 1 (low metastatic risk) or Class 2 transcriptional subtype (high metastatic risk) [7][14][7,14]. Four molecular subsets were proposed recently, based on more complex classification [15][16][15,16]. Besides chromosomal rearrangements, this also includes generally mutually exclusive secondary driver mutations with prognostic potential, occurring in the BAP1 (BRCA1-associated protein 1), EIF1AX (eukaryotic translation initiation factor 1A X-linked), or SF3B1 (splicing factor 3b subunit 1) genes [17].

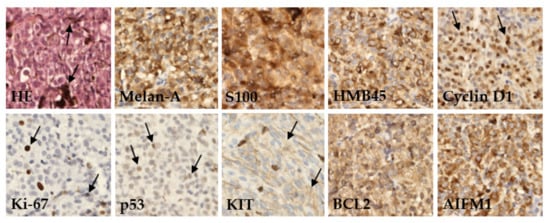

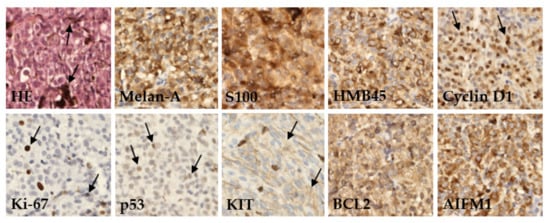

High expression of several immunohistochemical (IHC) markers in UM tumors, such as S100 (S100 calcium binding protein), Melan-A (Melanoma antigen recognized by T-cells 1), HMB45 (Human Melanoma Black), and some others, are regarded as clinically relevant diagnostic tools [18][19][18,19]. Cyclin D1 (Cyclin-D1-binding protein 1), Ki-67 (Proliferation marker protein Ki-67), and p53 (Cellular tumor antigen p53) positivities were linked with an unfavorable outcome [20]. Likewise, the overexpression of transmembrane tyrosine kinase receptor KIT (Mast/stem cell growth factor receptor Kit, alternative name CD117) was associated with poor prognosis in choroidal and ciliary body UM [21][22][21,22]. We recently identified 5-fold upregulation of its mRNA in M3 tumors compared to those with two copies of chromosome 3 (disomy 3, D3) [23]. In contrast to the normal ocular structures, UMs have also been characterized by upregulation of the anti-apoptotic protein BCL2 (Apoptosis regulator Bcl-2) [24]. Furthermore, we have shown that expression of AIFM1 (Apoptosis-inducing factor 1, mitochondrial), a protein with pro-apoptotic function in the nucleus and redox activity in mitochondria, was correlated with shorter survival in UM patients [25].

Epigenetic regulation plays the central role in time- and tissue-specific regulation of gene expression [26]. Epigenetic abnormalities contribute significantly to the development and progression of human malignancies. Deregulation of DNA methylation is one of the critical factors in resistance to current antitumoral therapies [27]. In close cooperation with histone modifications and noncoding RNA networks, DNA methylation controls normal cell development, chromatin stability, suppression of repetitive elements, and retrotransposition. Global hypomethylation occurs early in carcinogenesis, responsible for chromosomal instability and loss of imprinting [28]. Hypermethylation, associated with epigenetic silencing, is observed at multiple CpG sites in the regulatory regions of the genes, including CpG islands, shores, and shelves present inside or upstream of protein-coding genes promoters. Given the reversible nature of epigenetic changes, DNA methylation-based biomarkers have the potential to transform cancer diagnostics and treatment [29].

2. Clinicopathologic Characteristics of the Patients

In the present study, 51 UM patients were enrolled between August 2018 and September 2020; nine (17.6%) had detectable metastases at the time of primary tumor diagnosis, one developed metastases eight months after surgery (Table 1). Only patients who underwent enucleation without prior treatment (70.6%) or enucleation after radiation therapy in the past (29.4%) were included. Their age ranged between 32 and 87 years, with a median of 65 years. The patient sex ratio was similar; male patients comprised 51.0%, female 49.0%. The right eyes were affected more often (56.9% right eye, 43.1% left eye). The majority of UMs (78.4%) arose from the choroid (C69.3), followed by the ciliary body (21.6%; C69.4). 51.0% of tumors were defined as spindle-cell, while 47.0% as epithelioid or mixed. A locally advanced disease, characterized by vascular cell invasion, was diagnosed in 17.6% cases, with lymphogenic invasion at 29.4%, perineural spread at 23.5%, and extrabulbar overgrowth detected in 15.7% of patients. No significant differences between studied clinicopathologic features in primary and metastatic patients were found except for extrabulbar overgrowth, more frequent in metastatic patients (40% vs. 9.8%) (Table 1).

Table 1. Clinicopathologic characteristics of the enrolled patients.

| Clinicopathologic Characteristics |

All n (%) |

Primary UM n (%) |

Metastatic UM n (%) |

p-Value |

|---|

Figure 1. Immunohistochemical detection of various marker proteins’ expression in UM. In basic histological staining with hematoxylin and eosin (HE), the tumor cells showed a variable level of melanin content (arrows). In most cases, the tumors expressed melanoma markers like Melan-A, S100, and HMB45; variable amounts of prognostic markers as anti-apoptotic protein BCL2, Cyclin D1, tumor-suppressor protein p53, AIFM1, KIT protein, and proliferation rate protein Ki-67. Immunoperoxidase technique, diaminobenzidine, 200×.

Protein expression was categorized based on published cutoff values into two categories, defined herein as positive or negative. The examined tumor tissues were characterized by a high frequency of positive Melan-A (96.0%), HMB45 (94.0%), and S100 (92.0%). Furthermore, a high expression level was found for AIFM1 (91.5%) and Cyclin D1 (84.0%) proteins. Conversely, the highest frequency of negative protein expression was detected for Ki-67 (74.0%) and p53 (70.0%). Differences in expression of these proteins between patients diagnosed with primary or metastatic disease were not significant (Table 2).

Table 2. Protein expression of studied IHC markers.

| IHC Markers | All n (%) |

Primary UM n (%) |

Metastatic UM n (%) |

p-Value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||||||||

| Melan-A | |||||||||

| Male | 26 (51.0) | 23 (56.1) | 3 (30.0) | 0.139 | |||||

| Positive, ≥25% | 48 (96.0) | 38 (95.0) | 10 (100.0) | Female | 25 (49.0) | 18 (43.9) | 7 (70.0) | ||

| Eye | |||||||||

| Right | 29 (56.9) | 25 (61.0) | 4 (40.0) | 0.230 | |||||

| Left | 22 (43.1) | 16 (39.0) | 6 (60.0) | ||||||

| Median age (range) | 65.0 years (32–87) |

66.5 years (35–80) |

63.0 years (32–87) |

0.658 | |||||

| Median tumor volume (range) | 1.3 cm3 (0.3–2.6) | 1.3 cm3 (0.3–2.6) | 1.45 cm3 (0.3–2.6) | 0.694 | |||||

| <1.55 cm3 | 34 (66.7) | 27 (65.9) | 7 (70.0) | 0.803 | |||||

| 0.470 | ≥1.55 cm3 | 17 (33.3) | 14 (34.1) | 3 (30.0) | |||||

| Diagnosis | |||||||||

| C69.3 | 40 (78.4) | 34 (82.9) | 6 (60.0) | 0.114 | |||||

| C69.4 | 11 (21.6) | 7 (17.1) | 4 (40.0) | ||||||

| Cell type * | |||||||||

| Negative | 2 (4.0)Spindle | 26 (51.0) | 22 (53.7) | 4 (40.0) | 0.612 | ||||

| Epitheloid and Mixed | 24 (47.0) | 18 (43.9) | 6 (60.0) | ||||||

| Therapy | |||||||||

| Enucleation | 36 (70.6) | 27 (65.9) | 9 (90.0) | 0.133 | |||||

| Enucleation after SRS 1 | 15 (29.4) | 14 (34.1) | 1 (10.0) | ||||||

| 2 (5.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||||||||

| S100 | |||||||||

| Positive, ≥25% | 46 (92.0) | 37 (92.5) | 9 (90.0) | 0.794 | |||||

| Negative | 4 (8.0) | 3 (7.5) | 1 (10.0) | ||||||

| HMB45 | |||||||||

| Positive, ≥25% | 47 (94.0) | 38 (95.0) | 9 (90.0) | 0.552 | |||||

| Negative | 3 (6.0) | 2 (5.0) | 1 (10.0) | ||||||

| Cyclin D1 | |||||||||

| Positive, >15% | 42 (84.0) | 34 (85.0) | 8 (80.0) | 0.700 | |||||

| Negative | 8 (16.0) | 6 (15.0) | 2 (20.0) | ||||||

| Ki-67 | |||||||||

| Positive, >15% | 13 (26.0) | 9 (22.5) | 4 (40.0) | 0.259 | |||||

| Negative | 37 (74.0) | 31 (77.5) | 6 (60.0) | ||||||

| p53 | |||||||||

| Positive, >15% | 15 (30.0) | 12 (30.0) | 3 (30.0) | 1.000 | |||||

| Negative | 35 (70.0) | 28 (70.0) | 7 (70.0) | ||||||

| KIT | Vascular invasion | ||||||||

| Positive, >10% | 20 (41.7) | 15 (39.5) | 5 (50) | 0.548 | Present | 9 (17.6) | 6 (14.6) | 3 (30.0) | 0.253 |

| Absent | 42 (82.4) | 35 (85.4) | 7 (70.0) | ||||||

| Lymphogenic invasion | |||||||||

| Negative | 28 (58.3) | 23 (60.5) | 5 (50) | ||||||

| BCL2 | Present | 15 (29.4) | 10 (24.4) | 5 (50.0) | |||||

| Positive, ≥ ++ | 32 (68.1) | 0.111 | |||||||

| 25 (67.6) | 7 (70.0) | 0.884 | |||||||

| Negative | 15 (31.9) | 12 (32.4) | 3 (30.0) | Absent | |||||

| AIFM1 | 36 (70.6) | 31 (75.6) | 5 (50.0) | ||||||

| Perineural invasion | |||||||||

| Positive, QS | 1 > 4 | 43 (91.5) | 33 (89.2) | ||||||

| 10 (100.0) | 0.277 | Present | 12 (23.5) | 9 (22.0) | 3 (30.0) | 0.591 | |||

| Negative | 4 (8.5) | 4 (10.8) | 0 (0.0) | Absent | 39 (76.5) | 32 (78.0) | 7 (70.0) | ||

| Extrabulbar overgrowth | |||||||||

| Present | 8 (15.7) | 4 (9.8) | 4 (40.0) | 0.018 | |||||

| Absent | 43 (84.3) | 37 (90.2) | 6 (60.0) | ||||||

| TNM staging | |||||||||

| I–IIB | 23 (45.1) | 20 (48.8) | 3 (30.0) | 0.285 | |||||

| IIIA–C | 28 (54.9) | 21 (51.2) | 7 (70.0) |

1 Stereotactic radiosurgery in the past; * cell type was not determined in one sample due to a high degree of cell dedifferentiation and necrosis.

3. Immunohistochemistry

We performed an IHC analysis of nine proteins in UM tissues assessed as part of a routine pathological examination (Figure 1).

1 Quick score.

4. MLPA Analysis

Multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA) analysis was used to identify chromosomal rearrangements in UM samples. Only tumor tissues not treated by stereotactic radiosurgery in the past were analyzed. M3 was detected in 18 tumors (51.4%). MLPA identified 1p loss/partial loss in five patients (14.3%), 6q loss in four patients (11.4%), and 6q gain in three (8.6%) patients; 6p gain/partial gain, associated with a good prognosis, was found in 16 patients (45.7%). Chromosomal abnormalities were also found on chromosome 8, with 8p loss/partial loss in 12 cases (34.3%), 8p gain in one case (2.9%), and 8q gain/partial gain in 23 (65.7%) cases. UM-specific chromosomal changes were not found in one patient (2.9%) (Figure 2). As M3 strongly correlates with metastatic death, while chromosome 8 gains occur later in UM tumorigenesis, for further analysis, we categorized patients based on M3 presence into two categories, M3 vs. D3.

Figure 2. Presence of UM-specific chromosomal rearrangements detected by MLPA analysis. * partial loss/gain.

Acknowledgments: This research was funded by the APVV-17-0369 and VEGA 1/0395/21 projects.