Fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS) can be conceptualized as a chronic disorder characterized by widespread musculoskeletal pain and other accompanying symptoms such as fatigue, insomnia, depression, anxiety and cognitive impairments. The etiology of FMS remains unknown, being one of the most accepted hypothesis the presence of central sensitization to pain and impairments in endogenous pain inhibitory mechanisms. The history of the development of FMS concept reveals how other symptoms -apart from pain- has become also relevant in FMS diagnosis and treatment.

The central symptom of FMS is pain. FMS patients generally report high levels of clinical pain, which are related to greater impairments in health related quality of life, cognitive abilities and disease course. Fatigue and sleeping difficulties are also common symptoms of FMS. Fatigue have shown positive associations with pain, stiffness, sleep problems, increased body mass index, FMS severity, tenderness, disability, cognitive complaints, anxiety and depression. The majority of FMS patients report poor sleep quality, take longer to fall asleep, generally wake up during the night, sleep fewer hours, and usually wake up unrefreshed. Emotional disturbances (i.e., depression, anxiety) are also frequent in FMS. In fact, depression and anxiety disorders have showed a negative impact on the clinical course and work capacity of FMS patients. Cognitive impairments are also a relevant symptom in FMS. The most common complaints among FMS patients are executive function deficits, attention problems, forgetfulness, concentration difficulties, and mental slowness. Regarding the most frequent treatments for FMS, these can be classified as non-psychological and psychological. The former includes analgesic drugs, adjuvant drugs (i.e., antidepressants, benzodiazepines, anticonvulsants, etc.), nerve blocks, electrostimulation at different levels, infiltrations, etc. The psychological therapies with the most evidence are cognitive-behavioral, acceptance and commitment therapy and mindfulness.

FMS is associated with a severe reduction of health related quality of life and psychosocial impairments. It is necessary to take all FMS symptoms and its relations into account in order to provide a more tailored and effective treatment, as well as, to improve the health related quality of life of FMS patients.

- fibromyalgia

- pain

- fatigue

- insomnia

- depression

- anxiety

- cognitive impairments

1. Introduction

Fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS) can be conceptualized as a chronic disorder characterized by widespread musculoskeletal pain and other accompanying symptoms such as fatigue, insomnia and sleep related problems, depression, anxiety, and cognitive impairments. FMS prevalence in the general population has been estimated around 2 to 4%[1]. Prevalence data vary depending on the methods and the used diagnostic criteria[2]. Moreover, FMS has been traditionally considered more frequent in women than men[1]. However, recent studies point out that this sex difference in prevalence may be a result from biases studies[3] [4], suggesting the need of further studies in this field. Regarding the etiology of FMS, it remains unknown. One of the most accepted hypothesis is the presence of central sensitization to pain and impairments in endogenous pain inhibitory mechanisms[5] [6] [7]. See table 1 for more information. Nevertheless, other researchers have pointed out a neurological origin of FMS, based on the discovery of small fiber[8] [9] and large fiber[10] neuropathy in these patients[8]. Additionally, the involvement of idiopathic cerebrospinal pressure dysregulation in FMS pathology is still under discussion[11].

Table 1. Central sensitization to pain in Fibromyalgia Syndrome.[7]

|

Evidences of central sensitization to pain in Fibromyalgia Syndrome |

Main Authors |

|

Decreased threshold and tolerance to pain. |

Kosek 1997[12], Sorensen 1998[13], Carli 2002[14], Desmeules 2003[15], Petzke 2003[16], Reyes del Paso 2011[17]. |

|

Hyperalgesia and allodynia. |

Lee 2011[18], Arkue-Barretnexea 2007[19], Woolf 2011[20], Galvez-Sánchez 2018[21]. |

|

Deficits in descending pain inhibitory pathways. |

Julien 2005[22], Price 2005[23]. |

|

Supraspinal facilitation of the modulatory ascending pain pathways. |

Urban 1999[24], Gebhart 2004[25]. |

|

Alterations in cerebral blood flow modulation during painful stimulation. |

Duschek 2012[26], Montoro 2016[27]. |

|

Attenuated conditioned pain modulation (CPM). |

Kosek 1997[12], Julien 2005[22]. |

|

Enhanced sensitization / summation to repeated heat or pressure pain. |

Staud 2001[28], 2003[29], 2004[30]; de la Coba 2017[31], 2018[6]. |

|

Prolonged aftersensations after repeated mechanical and heat stimulation. |

Staud 2003[29], 2007[5], 2007[32]. |

|

Deficits in pain inhibitory systems. |

Henriksson 1994[33], Kosek 1997[12], Lautenbacher 1997[34]. - Reduction of serotonin and noradrenaline levels. Millan 2002[35], Russell 1992[36]. - Alterations in opioids system (opioidergic pathway). Julien 2005[22]. |

|

Higher levels of excitatory Central Nervous System (CNS) neurotransmitters, involved in enhancing wind-up and central sensitization. |

- Higher concentrations of substance P. Russell 1996[37], Russell 1998[38], Schwarz 1999[39], Banic 2004[40]. - Elevations in CNS glutamate levels. Harris, 2009[41], 2010[42]; Fayed 2010[43], Banic 2004[40]. |

|

Greater neuronal activation in the neuromatrix of pain. Increased gain or “volume setting” in brain pain-processing systems. |

Gracely 2002[7] Pujol 2009[44], Coghill 2003[45], Giesecke 2004[46], Gracely 2004[47]. |

|

More sensitive to pressure anywhere in their body (Note: tender points only represent regions where everyone is more tender)[48]. |

Kosek 1995[49], Wolfe 1997[50], Petzke 1999[51], Graven-Nielsen 2000[52]. |

|

More sensitive to other sensory stimuli such as sound. |

Gerster 1984[53], Dohrenbusch 1997[54], Geisser 2008[55]. |

In the history of the development of FMS concept, in 1977 H.A. Smythe and H. Moldofsky[56] continued the work of P.K. Hench[57], who coined the term fibromyalgia in 1976, and proposed the first measure for evaluating the disorder. H.A. Smythe is considered the grandfather of modern fibromyalgia, among other reasons, because he was the first to conceptualized fibromyalgia exclusively as a generalized pain syndrome, accompanied by other symptoms such as fatigue, nonrestorative sleep, morning stiffness, emotional distress, and multiple tender points. In addition, H.A. Smythe and H. Moldofsky proposed diagnostic criteria based on the core symptoms previously mentioned, stablishing an important precedent regarding the relevance of other symptoms -apart from pain- in FMS. Nevertheless, it was not until 1981 that the medical community accepted FMS as a real illness[58]. This medical recognition was influenced by the research of Yunus et al.[58] who proposed the first formal set of criteria to diagnose primary fibromyalgia, in which symptoms played a more central role in fibromyalgia diagnosis. As we previous mentioned, symptoms have been a relevant issue in FMS studies since its origins.

The evolution of FMS diagnostic criteria also reveals how symptoms have been acquiring more relevance over time. In 1990, the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) proposed the first official diagnostic criteria based on pain and using the tender point examination[1]. These first criteria were widely criticized because of their limited predictive validity of clinical pain and the difficulties of applying pressure algometry in primary health care[59] [60]. Due to of this, the ACR proposed new diagnostic criteria for FMS in 2010, in which nonrestorative sleep, fatigue and cognitive complaints have nearly equal weight for diagnosis and including depression, anxiety, irritable bowel syndrome, fatigue/tiredness, muscle weakness, Raynaud’s, ringing in ears, etc., as other secondary FMS symptoms. Moreover, the 2010 diagnostic criteria introduce the idea of widespread pain[61]. This interest in all FMS symptoms -not only in pain- continues in the new ACR FMS diagnostic proposals of 2011 (the modified 2010 ACR FMS diagnostic criteria)[62] and 2016[63]. Furthermore, some authors consider that the role and conceptualization of pain in FMS has evolved from the peripheral allodynia (tender points) of 1990 diagnostic criteria until the central pain perception and distress of 2016 FMS diagnostic proposal[64].

Chronic pain is a severe health problem, which has a high comorbidity with other physical and emotional alterations, such as anxiety, depression, insomnia and cognitive deficits[65]. These symptoms are also present in FMS patients. In the following lines, we will discuss these core FMS symptoms and their relations. Moreover, we will analyze why the comprehensive assessment of all of them may be challenging.

2. Pain

Undoubtedly, the central feature of FMS is pain. Pain has been defined by the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP)[66] as “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience, associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage”, including a subjective component and three main dimensions: the sensory-discriminative, the emotional-affective and the cognitive-evaluative. In the case of FMS pain is chronic because it is present more than 6 months. FMS patients almost always report high levels of clinical pain[67] [68] [69]. FMS patients frequently describe pain -i.e., based on pain descriptors from the McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ)- as throbbing, aching, exhausting, continuous, wretched, of fluctuating intensity, and with periodical exacerbations[70] [71] [72]. Traditionally, only pain intensity was routinely assessed in FMS using visual analogue scales (VAS), numeric rating scales (NRS) or specific questionnaires[73]. Nevertheless, other aspects of pain such as its location (i.e., how wide-spread it is), and its temporality (i.e., continuous vs. intermittent) are also relevant in FMS diagnosis and treatment[74]. Depression[75] [76] higher daily pain intensity[76] poor health, and lower quality of life[77] have been associated with greater pain variability, which make pain management more difficult for FMS patients and physicians.

In the same vein, pain has shown a negative impact on health related quality of life and also increases stress and negative affect, worsening the severity and course of the disease[67] [69] [78]. High levels of pain (especially its intensity and chronicity) together with the difficulties in its management, has been associated with poorer outcomes and a worse health related quality of life in FMS [67] [68] [69] [78] [79]. Several studies have reported significant associations between clinical pain and cognitive alterations in FMS[80] [81] [82] [83] [84] [85] [86] [87].

3. Fatigue

Fatigue[88] [89] [90] [91] [92] and sleeping difficulties (i.e., insomnia, awakening unrefreshed and daytime somnolence)[93] [94] [95] are also common symptoms of FMS. Regarding fatigue, it is conceptualized as a condition related to an exercise-induced reduction in the ability to produce force, which determines whether performance of the task can be maintained[96]. In FMS it is important to keep in mind that we are usually talking about chronic fatigue, which is a disabling, multifaceted and persistent symptom, not a circumstantial or exercise-associated problem. The concomitance of pain and fatigue in FMS is frequent, and the pathophysiology of this link is heterogeneous and not seem to have a single underlying mechanism;[97] which might be one of the reason of the high comorbidity of FMS and Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. At this regard, some authors suggest two explanatory interconnected mechanisms explaining fatigue in FMS: a failure of central motor control and the remodelling of the muscle fibres related to an altered suprasegmental control[98]. Some authors claim for a standardized nomenclature to communicate about fatigue, increase the evidence-based guidelines for fatigue assessment, and design effective treatment strategies[99], which consequently could improve the FMS diagnosis and treatment.

Fatigue in FMS patients seems to be highest in the morning[100], although more research on this issue is required[101]. Fatigue has been also associated with poorer health status in FMS, given that the lack of energy limits daily activities and reduces the ability to cope with everyday problems[88]. Pain, stiffness, sleep problems, increased body mass index, FMS impact, tenderness, disability, cognitive complaints, anxiety and depression have shown positive associations with fatigue[102] [103]. However, because of the lack of consensus and a standard protocol for assessing fatigue in FMS, the meaning of these associations should be carefully interpreted[2]. In addition, fatigue mediated in part the effect of depression, trait-anxiety and pain on health related quality of life in FMS, specifically concerning the facets of Physical Function, Physical Role, Vitality, General Health Perception and the General Physical Component[68].

4. Sleep Difficulties

Related to sleep difficulties, the majority of FMS patients report poor sleep quality[104] [105] [106] [107]. Patients take longer to fall asleep, generally wake up during the night, sleep fewer hours, and usually wake up unrefreshed in comparison with healthy controls, and patients with other rheumatic diseases or other pain disorders[108] [109]. Defficient stage IV (deep sleep) has been considered as the primary sleep architecture abnormality in FMS[110]. FMS patients usually show an increased frequency of α-rhythms during non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep compared to controls[106] [111] [112] [113]. α EEG frequencies are frequently related to wakefulness and it has been hypothesized that this increased α activity during NREM sleep was responsible for the nonrestorative sleep pattern in FMS patients[106] [111] [112] [113]. In addition, increased sleep latency, more frequent stage shifts, and shorter total sleep time have been also observed in FMS patients[111] [114] [115] [116]. FMS patients may also experience primary sleep disorders such as obstructive sleep apnea, myoclonus, or periodic leg movements[117] [118] [119].

Regarding the relation between insomnia and other symptoms, sleep difficulties seem to increase fatigue and anxiety, increasing functional disability in FMS[69]. Furthermore, sleep disturbances and pain appear to have a bidirectional relation in FMS[93] [117] [120]. Previous researchers have also found associations between sleep problems and health related quality of life in FMS[121]. In fact, insomnia has a mediating effect on the associations between pain, trait-anxiety, depression and fatigue with Vitality and Physical Function, measured with the Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36)[68].

Sleep disturbances in FMS are associated with reductions in serotonin and endorphin levels, as well as increases in substance P and sympathetic nervous system activity[65] [69] [122],all of which might be related to the presence of central pain sensitization in FMS. Additionally, sleep problems have been associated with neuroendocrine and immune impairments in FMS, indicating the possible role of sleep difficulties not only as a consequence of the FMS, but also as a cause[69]. Furthermore, Hamilton et al. (2007)[123] pointed out that sleep might be a resource in, and moderator of, cognitive and affective responses to stress and pain in FMS patients. It is recommended to ensure basic sleep hygiene in FMS patients, including this intervention as part of an initial psychoeducational approach[124]. Moreover, improvements in sleep quality might offset the negative effects of pain on sustained attention[125].

5. Emotional Disturbances

Emotional disturbances (i.e., depression, anxiety) are also frequent in FMS patients. Previous researchers underscore that depressive and anxiety disorders are highly prevalent in FMS,[1] [126] [127] [128] and in consequence, a high proportion of these patients take antidepressants and anxiolytic medications, together with analgesic drugs[84] [129]. On purpose, the intake of antidepressants, anxiolytics and non-opioid medications has been related to a worse heath related quality of life in FMS[68] [129].

Depression and anxiety disorders have showed a negative impact on the clinical course and work capacity of FMS patients[78] [130]. At this regard, comorbid depression and anxiety has been associated in FMS with lower scores on health related quality of life and greater disease severity[126] [129] [131] [132] [133] [134][135], as well as with a reduction in the ability to cope with life events[92].

Trait anxiety -buy not state anxiety- has been related to current pain intensity, suggesting that anxious mood could be a predisposing factor instead of a reaction to the disease[136]. Previous studies also reported a high association between symptoms of anxiety and depression[137] [138] [139].

FMS patients with depressive symptoms usually show more sleep disturbances, sexual dysfunction, lower levels of physical function and poorer outcomes in multimodal rehabilitation[140]. Depression and pain seem to establish a vicious circle of mutual negative interaction in chronic pain,[141] including FMS[129]. Pain seems to increase the degree of depression-anxiety and then increases the perception of pain, leading to decreases in health related quality of life[142]. Negative emotional states in FMS need to be taken into account due to its negative effect in the rest of symptoms. In fact, negative affect appears to worsen symptom perception and disability by different mechanisms, including increased interoceptive attention and somatosensory and symptom amplification[143]. The assessment of depression, anxiety and affect in general should be included in the diagnostic routine of FMS in order to better understand and treat these patients.

6. Cognitive Impairments

Cognitive impairments are also a relevant symptom in FMS. The most common complaints among FMS patients are deficits in executive functions, forgetfulness, concentration difficulties, and/or mental slowness[84] [144] [145] [146].

Previous studies have reported that FMS patients displayed lower performance than healthy controls in tasks which assessed:

- Attention and memory functions[84] [144] [145] [146] [147] [148].

- Cognitive processing speed[85] [144] [148] [149] [150].

- Language-related skills[151] [152] [153].

- Arithmetic processing[84] [85].

- Abstract thinking[148] [154].

- Planning abilities[148] [149] [155].

- Decision making[148] [155] [156].

- Cognitive flexibility[148] [155] [157].

Cognitive deficits significantly affect the everyday life of FMS patients, which patients perceiving cognitive symptoms as one of the most worrisome and disabling symptoms of FMS[126] [158].

Regarding to the mechanisms involved in these cognitive deficits, there are different findings but more research is required. The interference effects of nociception and pain have been considered an important factor[84] [85] [146] [159] [160]. In the same vein, it has been found associations between cognitive performance and evoked pain stimulation measures and behavioral indices as pain threshold and tolerance, including pressure algometry[21] [150] [159] [161] [162] [163], contact thermode[164], and/or conditioned pain modulation[162] [163]. Affective symptoms of FMS might be additionally related to cognitive deficits[85]. Lower cognitive performance has been associated with higher pain severity, depression, anxiety, negative affect, alexithymia and pain catastrophizing, as well as lower self-esteem and positive affect[148]. Cognitive deficits have been also related to fatigue and insomnia in FMS[102] [103].

7. Other relevant issues regarding symptoms of Fibromyalgia Syndrome

There are also other great variety of symptoms that usually accompany FMS, for instance dizziness and vertigo[165], increased urinary frequency[166], temporomandibular symptoms[167], intolerance cold[168], alteration of bowel habits[169], tension headaches[168], morning stiffness, abdominal pain, hypersensitivity to heat, cold and stress[170], corneal sensitivity and complaints of ocular discomfort and pain[171], and hearing loss[172], among others.

Previous studies have shown some factors which worsen FMS symptoms and might be associated with disease exacerbations. Some of the most relevant factors are stress and negative life events, emotional distress, weather changes, cold, periods of exacerbated insomnia, and physical exercise. By contrast, rest, relaxation, social support and warmth are considered relief factors by the majority of FMS patients[104] [173].

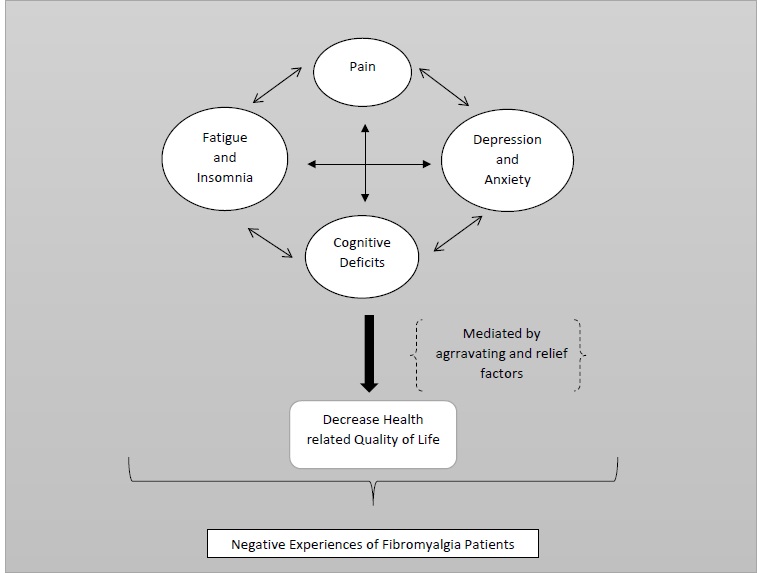

Another relevant issue is related to the complex nature of FMS symptoms, because pain and the majority of FMS symptoms do not have a clear origin, provoking discomfort in FMS patients and a lack of social support and/or medical and social acceptance[2] [174]. Moreover, these symptoms are always present in the majority of patients and exhibit a high variability (i.e., their intensity changes from day to day and within the day) which make their treatment and prevention more difficult[175] [176] [177] [178]. The current available evidence points out a complex picture, in which clinical and emotional symptoms affected each other and have a reciprocal mutual enhancing influence in FMS[68] [129].

Due to the symptomatology and characteristics of FMS, this illness is associated with a severe reduction of health related quality of life and psychosocial impairments[68] [126] [129] [130] [142] [179]. In fact, FMS considerably reduces perceived functioning in physical, psychological, and social spheres, and has a negative impact on personal relationships, parenting, work, daily activities, mental health and social life[180] [181].

Therefore, it is necessary to take all FMS symptoms and its relations into account in order to provide a more tailored and effective treatment, as well as, to improve the health related quality of life of FMS patients. See Figure 1 for more details.

Figure 1. Fibromyalgia Syndrome Symptoms’ and its associations.

8. Fibromyalgia Syndrome Treatment

Regarding the most frequent treatments for FMS, these can be classified as non-psychological and psychological. The former includes analgesic drugs (steroidal and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, minor opiates, major opiates, non-opiate analgesic, etc.), adjuvant drugs (which are not analgesics but enhance their action: antidepressants, benzodiazepines, anticonvulsants, etc.), nerve blocks, electrostimulation at different levels, infiltrations, etc. Additionally, it is recommended not include opiates in the treatment and avoid patients become poly pharmacies[2]. Among the non-psychological treatments are also physiotherapy and occupational therapy[182].

The psychological therapies with the most evidence are cognitive-behavioral, acceptance and commitment therapy and mindfulness[183]. The psychological treatments also encompass biofeedback, relaxation, alternative therapies (i.e., yoga, acupuncture, Pilates, mindfulness), visual imagery techniques, hypnosis and sexual therapies[65] [184]. Furthermore, it is advisable to use patient-reported outcomes (PROs) in FMS to get a better understanding of the disease[74]. PROs have been defined as "any report of the status of a patient's health condition that comes directly from the patient, without interpretation of the patient's response by a clinician or anyone else." PRO tools enable assessment of patient–reported health status for physical, mental, and social well-being (PROs)[185].

9. Conclusions

In short, FMS is defined as a chronic disorder characterized by widespread musculoskeletal pain and other accompanying symptoms such as fatigue, insomnia, depression, anxiety and cognitive impairments. The etiology of FMS remains unknown, being one of the most accepted hypothesis the presence of central sensitization to pain and impairments in endogenous pain inhibitory mechanisms.

The central symptom of FMS is pain. FMS patients generally report high levels of clinical pain, which are related to greater impairments in health related quality of life, cognitive abilities and disease course. Fatigue and sleeping difficulties are also common symptoms of FMS. Fatigue have shown positive associations with pain, stiffness, sleep problems, increased body mass index, FMS severity, tenderness, disability, cognitive complaints, anxiety and depression. The majority of FMS patients report poor sleep quality, take longer to fall asleep, generally wake up during the night, sleep fewer hours, and usually wake up unrefreshed. Emotional disturbances (i.e., depression, anxiety) are also frequent in FMS. Depression and anxiety disorders have showed a negative impact on the clinical course and work capacity of FMS patients. Cognitive impairments are also a relevant symptom in FMS. The most common complaints among FMS patients are executive function deficits, attention problems, forgetfulness, concentration difficulties, and mental slowness. Treatments for FMS can be classified as non-psychological and psychological. The former includes analgesic drugs, adjuvant drugs (i.e., antidepressants, benzodiazepines, anticonvulsants, etc.), nerve blocks, electrostimulation at different levels, infiltrations, etc. The psychological therapies with the most evidence are cognitive-behavioral, acceptance and commitment therapy and mindfulness.

To sum up, FMS is associated with a severe reduction of health related quality of life and psychosocial impairments. It is necessary to take all FMS symptoms and its relations into account in order to provide a more tailored and effective treatment, as well as, to improve the health related quality of life of FMS patients.

References

- Frederick Wolfe; Hugh A. Smythe; Muhammad B. Yunus; Robert M. Bennett; Claire Bombardier; Don L. Goldenberg; Peter Tugwell; Stephen Campbell; Micha Abeles; Patricia Clark; et al.Adel G. FamStephen J. FarberJustus J. FiechtnerC. Michael FranklinRobert A. GatterDaniel HamatyJames LessardAlan S. LichtbrounAlfonse T. MasiGlenn A. McCainW. John ReynoldsThomas J. RomanoI. Jon RussellRobert P. Sheon The american college of rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of fibromyalgia. Arthritis Care & Research 1990, 33, 160-172, 10.1002/art.1780330203.

- Andrea T. Borchers; M. E. Gershwin; Fibromyalgia: A Critical and Comprehensive Review. Clinical Reviews in Allergy & Immunology 2015, 49, 100-151, 10.1007/s12016-015-8509-4.

- Sachin Srinivasan; Eamon Maloney; Brynn Wright; Michael Kennedy; K. James Kallail; Johannes J. Rasker; Winfried Häuser; Frederick Wolfe; The Problematic Nature of Fibromyalgia Diagnosis in the Community.. ACR Open Rheumatology 2019, 1, 43-51, 10.1002/acr2.1006.

- Frederick Wolfe; Brian Walitt; Serge Perrot; Johannes J. Rasker; Winfried Häuser; Fibromyalgia diagnosis and biased assessment: Sex, prevalence and bias. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0203755, 10.1371/journal.pone.0203755.

- Roland Staud; Euna Koo; Michael E. Robinson; Donald D. Price; Spatial summation of mechanically evoked muscle pain and painful aftersensations in normal subjects and fibromyalgia patients. Pain 2007, 130, 177-187, 10.1016/j.pain.2007.03.015.

- Pablo De La Coba; Stephen Bruehl; Carmen M. Galvez Sánchez; Gustavo A. Reyes Del Paso; SLOWLY REPEATED EVOKED PAIN (SREP) AS A MARKER OF CENTRAL SENSITIZATION IN FIBROMYALGIA. Psychosomatic Medicine 2018, 80, 573-580, 10.1097/psy.0000000000000599.

- Richard H. Gracely; Frank Petzke; Julie M. Wolf; Daniel Clauw; Functional magnetic resonance imaging evidence of augmented pain processing in fibromyalgia. Arthritis Care & Research 2002, 46, 1333-1343, 10.1002/art.10225.

- Khosro Farhad; Anne Louise Oaklander; Fibromyalgia and small-fiber polyneuropathy: What's in a name?. Muscle & Nerve 2018, 58, 611-613, 10.1002/mus.26179.

- Manuel Martínez-Lavín; Fibromyalgia and small fiber neuropathy: the plot thickens!. Clinical Rheumatology 2018, 37, 3167-3171, 10.1007/s10067-018-4300-2.

- Xavier J. Caro; Robert G. Galbraith; Earl F. Winter; Evidence of peripheral large nerve involvement in fibromyalgia: a retrospective review of EMG and nerve conduction findings in 55 FM subjects. European Journal of Rheumatology 2018, 5, 104-110, 10.5152/eurjrheum.2018.17109.

- M Hulens; W. Dankaerts; I. Stalmans; A. Somers; G. VanSant; R. Rasschaert; F. Bruyninckx; Fibromyalgia and unexplained widespread pain: The idiopathic cerebrospinal pressure dysregulation hypothesis. Medical Hypotheses 2018, 110, 150-154, 10.1016/j.mehy.2017.12.006.

- Eva Kosek; Per Hansson; Modulatory influence on somatosensory perception from vibration and heterotopic noxious conditioning stimulation (HNCS) in fibromyalgia patients and healthy subjects. Pain 1997, 70, 41-51, 10.1016/s0304-3959(96)03295-2.

- J Sörensen; Thomas Graven-Nielsen; K G Henriksson; M Bengtsson; L. Arendt-Nielsen; Hyperexcitability in fibromyalgia.. The Journal of Rheumatology 1998, 25, 152-155.

- Giancarlo Carli; Anna Lisa Suman; Giovanni Biasi; Roberto Marcolongo; Reactivity to superficial and deep stimuli in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain. Pain 2002, 100, 259-269, 10.1016/s0304-3959(02)00297-x.

- Jules A. Desmeules; C. Cedraschi; E. Rapiti; E. Baumgartner; Axel Finckh; P. Cohen; P. Dayer; T. L. Vischer; Neurophysiologic evidence for a central sensitization in patients with fibromyalgia. Arthritis Care & Research 2003, 48, 1420-1429, 10.1002/art.10893.

- Frank Petzke; Daniel J Clauw; Kirsten Ambrose; Albert Khine; Richard H. Gracely; Increased pain sensitivity in fibromyalgia: effects of stimulus type and mode of presentation.. Pain 2003, 105, 403-413, 10.1016/S0304-3959(03)00204-5.

- Gustavo A. Reyes Del Paso; Sergio Garrido; Ángeles Pulgar; Stefan Duschek; Autonomic cardiovascular control and responses to experimental pain stimulation in fibromyalgia syndrome. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 2011, 70, 125-134, 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2010.09.012.

- Yvonne C. Lee; Nicholas J Nassikas; Daniel Clauw; The role of the central nervous system in the generation and maintenance of chronic pain in rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis and fibromyalgia.. Arthritis Research & Therapy 2011, 13, 211-211, 10.1186/ar3306.

- Jon Jatsu Azkue; Vicente Ortiz; Fernando Torre; Luciano Aguilera; La Sensibilización Central en la fisiopatología del dolor. Gaceta Médica de Bilbao 2007, 104, 136-140, 10.1016/s0304-4858(07)74593-6.

- Clifford J. Woolf; Central sensitization: Implications for the diagnosis and treatment of pain. Pain 2011, 152, S2-S15, 10.1016/j.pain.2010.09.030.

- Carmen M. Galvez Sánchez; Cristina Muñoz Ladrón De Guevara; Casandra Montoro; María José Fernández-Serrano; Stefan Duschek; Gustavo A. Reyes Del Paso; Cognitive deficits in fibromyalgia syndrome are associated with pain responses to low intensity pressure stimulation. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0201488, 10.1371/journal.pone.0201488.

- Nancy Julien; Philippe Goffaux; Pierre Arsenault; Serge Marchand; Widespread pain in fibromyalgia is related to a deficit of endogenous pain inhibition. Pain 2005, 114, 295-302, 10.1016/j.pain.2004.12.032.

- Donald D. Price; Roland Staud; Neurobiology of fibromyalgia syndrome.. The Journal of Rheumatology Supplement 2005, 75, 22-8.

- M. O. Urban; G.F. Gebhart; Supraspinal contributions to hyperalgesia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1999, 96, 7687-7692, 10.1073/pnas.96.14.7687.

- G.F. Gebhart; Descending modulation of pain. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 2004, 27, 729-737, 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2003.11.008.

- Stefan Duschek; Nicolette Hellmann; Karim Merzoug; Gustavo A. Reyes Del Paso; Natalie S. Werner; Cerebral Blood Flow Dynamics During Pain Processing Investigated by Functional Transcranial Doppler Sonography. Pain Medicine 2012, 13, 419-426, 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2012.01329.x.

- Casandra I. Montoro; Stefan Duschek; Cristina Muñóz Ladrón De Guevara; Gustavo A. Reyes Del Paso; Patterns of Cerebral Blood Flow Modulation During Painful Stimulation in Fibromyalgia: A Transcranial Doppler Sonography Study. Pain Medicine 2016, 17, 2256-2267, 10.1093/pm/pnw082.

- Roland Staud; Charles J. Vierck; Richard L. Cannon; Andre P. Mauderli; Donald D. Price; Abnormal sensitization and temporal summation of second pain (wind-up) in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome. Pain 2001, 91, 165-175, 10.1016/s0304-3959(00)00432-2.

- Roland Staud; Richard C Cannon; Andre P Mauderli; Michael E Robinson; Donald D Price; Charles J Vierck; Temporal summation of pain from mechanical stimulation of muscle tissue in normal controls and subjects with fibromyalgia syndrome. Pain 2003, 102, 87-95, 10.1016/s0304-3959(02)00344-5.

- Roland Staud; Charles J. Vierck; Michael E. Robinson; Donald D. Price; Spatial summation of heat pain within and across dermatomes in fibromyalgia patients and pain-free subjects. Pain 2004, 111, 342-350, 10.1016/j.pain.2004.07.015.

- Pablo De La Coba; Stephen Bruehl; María Moreno Padilla; Gustavo A. Reyes Del Paso; Responses to Slowly Repeated Evoked Pain Stimuli in Fibromyalgia Patients: Evidence of Enhanced Pain Sensitization. Pain Medicine 2017, 18, 1778-1786, 10.1093/pm/pnw361.

- Roland Staud; Michael E. Robinson; Donald D. Price; Temporal Summation of Second Pain and Its Maintenance Are Useful for Characterizing Widespread Central Sensitization of Fibromyalgia Patients. The Journal of Pain 2007, 8, 893-901, 10.1016/j.jpain.2007.06.006.

- Henriksson, K.G., Mense, S.; Pain and nociception in fibromyalgia: Clinical and neurobiological considerations on aetiology and pathogenesis. Pain Reviews 1994, 1, 245-260.

- S. Lautenbacher; G. B. Rollman; G. A. McCain; Multi-method assessment of experimental and clinical pain in patients with fibromyalgia. Pain 1994, 59, 45-53, 10.1016/0304-3959(94)90046-9.

- Mark J Millan; Descending control of pain. Progress in Neurobiology 2002, 66, 355-474, 10.1016/s0301-0082(02)00009-6.

- I. Jon Russell; Henning Vaeroy; Martin Javors; Fred Nyberg; Cerebrospinal fluid biogenic amine metabolites in fibromyalgia/fibrositis syndrome and rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care & Research 1992, 35, 550-556, 10.1002/art.1780350509.

- Russell IJ, Vipraio G, Fletcher EM, Lopez YM, Orr MD, Michalek JE.; Characteristics of spinal fluid (CSF) substance p (SP) and calcitonin gene related peptide (CGRP) in fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS).. Arthritis & Rheumatism 1996, 39, S275.

- I. J. Russell; Neurochemical pathogenesis of fibromyalgia.. Zeitschrift für Rheumatologie 1998, 57, S63-S66, 10.1007/s003930050238.

- M.J. Schwarz; Michael Späth; Hanns Müller-Bardorff; Dieter E Pongratz; B Bondy; Manfred Ackenheil; Relationship of substance P, 5-hydroxyindole acetic acid and tryptophan in serum of fibromyalgia patients. Neuroscience Letters 1999, 259, 196-198, 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00937-9.

- Borut Banic; Steen Petersen-Felix; Ole Kæseler Andersen; Bogdan P Radanov; M P. Villiger; L. Arendt-Nielsen; Michele Curatolo; P.M Villiger; Evidence for spinal cord hypersensitivity in chronic pain after whiplash injury and in fibromyalgia. Pain 2004, 107, 7-15, 10.1016/j.pain.2003.05.001.

- Richard E. Harris; Pia C. Sundgren; A.D. (Bud) Craig; Eric Kirshenbaum; Ananda Sen; Vitaly Napadow; Daniel J. Clauw; Elevated insular glutamate in fibromyalgia is associated with experimental pain. Arthritis Care & Research 2009, 60, 3146-3152, 10.1002/art.24849.

- Richard E. Harris; Elevated excitatory neurotransmitter levels in the fibromyalgia brain. Arthritis Research & Therapy 2010, 12, 141-141, 10.1186/ar3136.

- N Fayed-Miguel; Javier Garcia-Campayo; Rosa Magallón; Helena Andrés-Bergareche; Juan V. Luciano; Eva Andrés; Julián Beltrán; Localized 1H-NMR spectroscopy in patients with fibromyalgia: a controlled study of changes in cerebral glutamate/glutamine, inositol, choline, and N-acetylaspartate. Arthritis Research & Therapy 2010, 12, R134-R134, 10.1186/ar3072.

- Jesus Pujol; Marina López-Solà; Héctor Ortiz; Joan C. Vilanova; Ben J. Harrison; Murat Yucel; Carles Soriano-Mas; Narcís Cardoner; Joan Deus; Mapping Brain Response to Pain in Fibromyalgia Patients Using Temporal Analysis of fMRI. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e5224, 10.1371/journal.pone.0005224.

- Robert C Coghill; John G. McHaffie; Yi-Fen Yen; Neural correlates of interindividual differences in the subjective experience of pain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2003, 100, 8538-8542, 10.1073/pnas.1430684100.

- Thorsten Giesecke; Richard H. Gracely; Masilo A. B. Grant; Alf Nachemson; Frank Petzke; David A. Williams; Daniel J. Clauw; Evidence of augmented central pain processing in idiopathic chronic low back pain. Arthritis Care & Research 2004, 50, 613-623, 10.1002/art.20063.

- R. H. Gracely; M. E. Geisser; T. Giesecke; M. A. B. Grant; F. Petzke; D. A. Williams; Daniel Clauw; Pain catastrophizing and neural responses to pain among persons with fibromyalgia. Brain 2004, 127, 835-843, 10.1093/brain/awh098.

- K.A. Sluka; Daniel J. Clauw; Neurobiology of fibromyalgia and chronic widespread pain.. Neuroscience 2016, 338, 114-129, 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2016.06.006.

- Eva Kosek; Jan Ekholm; Per Hansson; Increased pressure pain sensibility in fibromyalgia patients is located deep to the skin but not restricted to muscle tissue. Pain 1995, 63, 335-339, 10.1016/0304-3959(95)00061-5.

- Frederick Wolfe; The relation between tender points and fibromyalgia symptom variables: evidence that fibromyalgia is not a discrete disorder in the clinic. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 1997, 56, 268-271, 10.1136/ard.56.4.268.

- Petzke F, Ambrose K, Gracely RH, Clauw DJ.; What do tender points measure?. Arthritis & Rheumatism 1999, 42, S342.

- Thomas Graven-Nielsen; Sally Aspegren Kendall; Karl G. Henriksson; Mats Bengtsson; Jan Sörensen; Anders Johnson; Björn Gerdle; L. Arendt-Nielsen; Ketamine reduces muscle pain, temporal summation, and referred pain in fibromyalgia patients. Pain 2000, 85, 483-491, 10.1016/s0304-3959(99)00308-5.

- J C Gerster; A Hadj-Djilani; Hearing and vestibular abnormalities in primary fibrositis syndrome.. The Journal of Rheumatology 1984, 11, 678-680.

- R. Dohrenbusch; H. Sodhi; J. Lamprecht; E. Genth; Fibromyalgia as a disorder of perceptual organization? An analysis of acoustic stimulus processing in patients with widespread pain (Fibromyalgie als Störung der Wahrnehmungsorganisation? Eine Analyse akustischer Reizverarbeitung bei Patienten mit generalisiertem Schmerz). Zeitschrift für Rheumatologie 1997, 56, 334-341, 10.1007/s003930050047.

- Michael E PhD Geisser; Jennifer M. Glass; Ljubinka D. Rajcevska; Daniel J. Clauw; David A. Williams; Paul R. Kileny; Richard H. Gracely; A Psychophysical Study of Auditory and Pressure Sensitivity in Patients With Fibromyalgia and Healthy Controls. The Journal of Pain 2008, 9, 417-422, 10.1016/j.jpain.2007.12.006.

- Smythe, H.A.; Moldofsky, H.; Two contributions to understanding of the . Bull Rheum Dis 1977, 28, 928-931.

- Hench, P.K.; Nonarticular rheumatism, 22nd rheumatism review: review of the American and English literature for the years 1973 and 1974. Arthritis Rheumatology 1976, 19, 1081-1089.

- Muhammad Yunus; Alfonse T. Masi; John J. Calabro; Kenneth A. Miller; Seth L. Feigenbaum; Primary fibromyalgia (fibrositis): Clinical study of 50 patients with matched normal controls. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism 1981, 11, 151-171, 10.1016/0049-0172(81)90096-2.

- Frederick Wolfe; Editorial: the status of fibromyalgia criteria.. Arthritis & Rheumatology 2015, 67, 330-3, 10.1002/art.38908.

- A Okifuji; D C Turk; J D Sinclair; T W Starz; D A Marcus; A standardized manual tender point survey. I. Development and determination of a threshold point for the identification of positive tender points in fibromyalgia syndrome.. The Journal of Rheumatology 1997, 24, 377–383.

- Frederick Wolfe; Daniel J. Clauw; Mary-Ann Fitzcharles; Don L. Goldenberg; Robert S. Katz; Philip Mease; Anthony S. Russell; I. Jon Russell; John B. Winfield; Muhammad B. Yunus; et al. The American College of Rheumatology Preliminary Diagnostic Criteria for Fibromyalgia and Measurement of Symptom Severity. Arthritis Care & Research 2010, 62, 600-610, 10.1002/acr.20140.

- Frederick Wolfe; Daniel Clauw; Mary-Ann Fitzcharles; Don L. Goldenberg; Winfried Häuser; Robert S. Katz; Philip Mease; Anthony S. Russell; I. Jon Russell; John B. Winfield; et al. Fibromyalgia Criteria and Severity Scales for Clinical and Epidemiological Studies: A Modification of the ACR Preliminary Diagnostic Criteria for Fibromyalgia. The Journal of Rheumatology 2011, 38, 1113-1122, 10.3899/jrheum.100594.

- Frederick Wolfe; Daniel J. Clauw; Mary-Ann Fitzcharles; N L. Goldenberg; Winfried Häuser; Robert L. Katz; Philip Mease; Anthony S. Russell; Irwin Jon Russell; Brian Walitt; et al. 2016 Revisions to the 2010/2011 fibromyalgia diagnostic criteria. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism 2016, 46, 319-329, 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2016.08.012.

- Sakir Ahmed; Amita Aggarwal; Able Lawrence; Performance of the American College of Rheumatology 2016 criteria for fibromyalgia in a referral care setting. Rheumatology International 2019, 39, 1397-1403, 10.1007/s00296-019-04323-7.

- Martine M. Veehof; Maarten-Jan Oskam; Karlein M.G. Schreurs; E.T. Bohlmeijer; Acceptance-based interventions for the treatment of chronic pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain 2011, 152, 533-542, 10.1016/j.pain.2010.11.002.

- Pain IASP Taxonomy . International Association for the Study of Pain-IASP. Retrieved 2020-9-2

- Ernest Choy; Serge Perrot; Teresa Leon; Joan Kaplan; Danielle L. Petersel; Anna Ginovker; Erich Kramer; A patient survey of the impact of fibromyalgia and the journey to diagnosis. BMC Health Services Research 2010, 10, 102-102, 10.1186/1472-6963-10-102.

- Carmen M. Galvez Sánchez; Casandra Montoro; Stefan Duschek; Gustavo A. Reyes Del Paso; Depression and trait-anxiety mediate the influence of clinical pain on health-related quality of life in fibromyalgia. Journal of Affective Disorders 2020, 265, 486-495, 10.1016/j.jad.2020.01.129.

- Aysegul Kucukali Turkyilmaz; Emine Eda Kurt; Murat Karkucak; Erhan Çapkin; Sociodemographic Characteristics, Clinical Signs and Quality of Life in Patients with Fibromyalgia. The Eurasian Journal of Medicine 2012, 44, 88-93, 10.5152/eajm.2012.21.

- Giannapia Affaitati; Raffaele Costantini; Alessandra Fabrizio; Domenico Lapenna; Emmanuele Tafuri; Maria Adele Giamberardino; Effects of treatment of peripheral pain generators in fibromyalgia patients. European Journal of Pain 2011, 15, 61-69, 10.1016/j.ejpain.2010.09.002.

- S. Lautenbacher; G. B. Rollman; Possible Deficiencies of Pain Modulation in Fibromyalgia. The Clinical Journal of Pain 1997, 13, 189-196, 10.1097/00002508-199709000-00003.

- Hughes L; Physical and Psychological Variables That Influence Pain in Patients With Fibromyalgia. Orthopaedic Nursing 2006, 25(2), 120-121.

- Jensen, MP.; Karoly, P.. Self-report scales and procedures for assessing pain in adults. In Handbook of Pain Assessment.; DC, Turk; R, Melzack., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, 2011; pp. 19-44.

- David A PhD Williams; Anna L. Kratz; Patient-Reported Outcomes and Fibromyalgia.. Rheumatic Disease Clinics of North America 2016, 42, 317-32, 10.1016/j.rdc.2016.01.009.

- Stefan Schneider; Doerte U. Junghaenel; Francis J. Keefe; Joseph E. Schwartz; Arthur A. Stone; Joan E. Broderick; Individual differences in the day-to-day variability of pain, fatigue, and well-being in patients with rheumatic disease: Associations with psychological variables. Pain 2012, 153, 813-822, 10.1016/j.pain.2012.01.001.

- Karolina M. Zakoscielna; Patricia A. Parmelee; Pain Variability and Its Predictors in Older Adults. Journal of Aging and Health 2013, 25, 1329-1339, 10.1177/0898264313504457.

- Susan M Tupper; Alan M. Rosenberg; Punam Pahwa; Jennifer N. Stinson; Pain Intensity Variability and Its Relationship With Quality of Life in Youths With Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis. Arthritis Care & Research 2013, 65, 563-570, 10.1002/acr.21850.

- Ricardo Campos; Maria Isabel Rodríguez Vázquez; Health-related quality of life in women with fibromyalgia: clinical and psychological factors associated. Clinical Rheumatology 2011, 31, 347-355, 10.1007/s10067-011-1870-7.

- Marielza R. Ismael Martins; Letícia Oliveira Polvero; Carlos Eduardo Rocha; Marcos Henrique Foss; Randolfo Dos Santos Junior; Using questionnaires to assess the quality of life and multidimensionality of fibromyalgia patients.. Revista Brasileira de Reumatologia 2012, 52, 16-26.

- Ángel Correa; Elena Miró; M. Pilar Martínez; Ana I. Sánchez; Juan Lupiáñez; Temporal preparation and inhibitory deficit in fibromyalgia syndrome. Brain and Cognition 2011, 75, 211-216, 10.1016/j.bandc.2010.11.005.

- Jennifer M. Glass; David A. Williams; Maria-Luisa Fernandez-Sanchez; Anson Kairys; Paloma Barjola; Mary M. Heitzeg; Daniel J. Clauw; Tobias Schmidt-Wilcke; Executive function in chronic pain patients and healthy controls: different cortical activation during response inhibition in fibromyalgia.. The Journal of Pain 2011, 12, 1219-29, 10.1016/j.jpain.2011.06.007.

- K. Troy Harker; Raymond M. Klein; Bruce Dick; Michelle J. Verrier; Saifudin Rashiq; Exploring attentional disruption in fibromyalgia using the attentional blink. Psychology & Health 2011, 26, 915-929, 10.1080/08870446.2010.525639.

- Elena Miró; María Pilar Martínez; Ana Isabel Sánchez; Germán Prados; Ana Medina; When is pain related to emotional distress and daily functioning in fibromyalgia syndrome? The mediating roles of self-efficacy and sleep quality. British Journal of Health Psychology 2011, 16, 799-814, 10.1111/j.2044-8287.2011.02016.x.

- Casandra I. Montoro; Stefan Duschek; Cristina Muñóz Ladrón De Guevara; Maria José Fernández-Serrano; Gustavo A. Reyes Del Paso; Aberrant cerebral blood flow responses during cognition: Implications for the understanding of cognitive deficits in fibromyalgia.. Neuropsychology 2015, 29, 173-182, 10.1037/neu0000138.

- Gustavo A. Reyes Del Paso; Á. Pulgar; S. Duschek; S. Garrido; Cognitive impairment in fibromyalgia syndrome: The impact of cardiovascular regulation, pain, emotional disorders and medication. European Journal of Pain 2011, 16, 421-429, 10.1002/j.1532-2149.2011.00032.x.

- Lola Roldán-Tapia; Rosa Cánovas-López; José Cimadevilla; Matías Valverde; María D. Roldán-Tapia; Déficit mnésicos y perceptivos en la fibromialgia y la artritis reumatoide. Reumatología Clínica 2007, 3, 101-109, 10.1016/s1699-258x(07)73676-8.

- J. Suhr; Neuropsychological impairment in fibromyalgia: relation to depression, fatigue, and pain.. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 2003, 55, 321–329.

- Mónica Faro; N. Sáez Francàs; Jesus Castro-Marrero; Luisa Aliste; Antonio Collado; José Alegre; Impacto de la fibromialgia en el síndrome de fatiga crónica. Medicina Clínica 2014, 142, 519-525, 10.1016/j.medcli.2013.06.030.

- Nuray Akkaya; Semih Akkaya; Nilgun Simsir Atalay; C. B. Şengül; Fusun Sahin; Relationship between the body image and level of pain, functional status, severity of depression, and quality of life in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome. Clinical Rheumatology 2012, 31, 983-988, 10.1007/s10067-012-1965-9.

- Loren Toussaint; Ann Vincent; Samantha J. McAllister; Mary O. Whipple; Intra- and Inter-Patient Symptom Variability in Fibromyalgia: Results of a 90-Day Assessment. Musculoskeletal Care 2014, 13, 93-100, 10.1002/msc.1090.

- Carol A. Landis; Christine A. Frey; Martha J. Lentz; James Rothermel; Dedra Buchwald; Joan L.F. Shaver; Self-Reported Sleep Quality and Fatigue Correlates With Actigraphy in Midlife Women With Fibromyalgia. Nursing Research 2003, 52, 140-147, 10.1097/00006199-200305000-00002.

- Roland Staud; Chronic widespread pain and fibromyalgia: Two sides of the same coin?. Current Rheumatology Reports 2009, 11, 433-436, 10.1007/s11926-009-0063-8.

- Jan-Samuel Wagner; Marco daCosta DiBonaventura; Arthi Bala Chandran Mph; Joseph C. Cappelleri; The association of sleep difficulties with health-related quality of life among patients with fibromyalgia. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders 2012, 13, 199-199, 10.1186/1471-2474-13-199.

- Elena Miró; Juan Lupiáñez; E. Hita; M.P. Martínez; A.I. Sánchez; G. Buela-Casal; Attentional deficits in fibromyalgia and its relationships with pain, emotional distress and sleep dysfunction complaints. Psychology & Health 2011, 26, 765-780, 10.1080/08870446.2010.493611.

- Lily Neumann; Ella Lerner; Yael Glazer; Arkady Bolotin; Alexander Shefer; Dan Buskila; A cross-sectional study of the relationship between body mass index and clinical characteristics, tenderness measures, quality of life, and physical functioning in fibromyalgia patients. Clinical Rheumatology 2008, 27, 1543-1547, 10.1007/s10067-008-0966-1.

- Benjamin K. Barry; Roger M. Enoka; The neurobiology of muscle fatigue: 15 years later. Integrative and Comparative Biology 2007, 47, 465-473, 10.1093/icb/icm047.

- Patrick H. Finan; Alex J. Zautra; Fibromyalgia and Fatigue: Central Processing, Widespread Dysfunction. PM&R 2010, 2, 431-437, 10.1016/j.pmrj.2010.03.021.

- Roberto Casale; Piercarlo Sarzi-Puttini; Fabiola Atzeni; Marco Gazzoni; Dan Buskila; Alberto Rainoldi; Central motor control failure in fibromyalgia: a surface electromyography study. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders 2009, 10, 78-78, 10.1186/1471-2474-10-78.

- Ann Vincent; Roberto P Benzo; Mary O. Whipple; Samantha J McAllister; Patricia J Erwin; Leorey N. Saligan; Beyond pain in fibromyalgia: insights into the symptom of fatigue.. Arthritis Research & Therapy 2013, 15, 221-221, 10.1186/ar4395.

- N. Bellamy; Robert B Sothern; Jane Campbell; Aspects of diurnal rhythmicity in pain, stiffness, and fatigue in patients with fibromyalgia.. The Journal of Rheumatology 2004, 31, 379–89.

- E. B. Klerman; Circadian Rhythms of Women with Fibromyalgia. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2001, 86, 1034-1039, 10.1210/jc.86.3.1034.

- Brendt P. Parrish; Alex J. Zautra; Mary C. Davis; The role of positive and negative interpersonal events on daily fatigue in women with fibromyalgia, rheumatoid arthritis, and osteoarthritis.. Health Psychology 2008, 27, 694-702, 10.1037/0278-6133.27.6.694.

- María Correa-Rodríguez; Jamal El Mansouri-Yachou; Antonio Casas-Barragàn; Francisco Javier Molina-Ortega; Blanca Rueda-Medina; Encarnación Aguilar Ferrándiz; The Association of Body Mass Index and Body Composition with Pain, Disease Activity, Fatigue, Sleep and Anxiety in Women with Fibromyalgia.. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1193, 10.3390/nu11051193.

- Robert M. Bennett; Jessie Jones; Dennis C Turk; I. Jon Russell; Lynne Matallana; An internet survey of 2,596 people with fibromyalgia. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders 2007, 8, 27-27, 10.1186/1471-2474-8-27.

- Silvia M. Bigatti; Ann Marie Hernandez; Terry A. Cronan; Kevin L. Rand; Sleep disturbances in fibromyalgia syndrome: Relationship to pain and depression. Arthritis Care & Research 2008, 59, 961-967, 10.1002/art.23828.

- Suely Roizenblatt; Harvey Moldofsky; Ana Amelia Benedito-Silva; Sergio Tufik; Alpha sleep characteristics in fibromyalgia. Arthritis Care & Research 2001, 44, 222-230, 10.1002/1529-0131(200101)44:1<222::aid-anr29>3.0.co;2-k.

- Veli Çobankara; U. Olcun Unal; Arif Kaya; Ali Ihsan Bozkurt; Mehmet Akif Öztürk; The prevalence of fibromyalgia among textile workers in the city of Denizli in Turkey. International Journal of Rheumatic Diseases 2011, 14, 390-394, 10.1111/j.1756-185x.2011.01620.x.

- Carolina Diaz-Piedra; Leandro L. Di Stasi; Carol Baldwin; Gualberto Buela-Casal; Andrés Catena; Sleep disturbances of adult women suffering from fibromyalgia: A systematic review of observational studies. Sleep Medicine Reviews 2015, 21, 86-99, 10.1016/j.smrv.2014.09.001.

- Lars Cöster; Sally Kendall; Björn Gerdle; Chris Henriksson; Karl G. Henriksson; Ann Bengtsson; Chronic widespread musculoskeletal pain - A comparison of those who meet criteria for fibromyalgia and those who do not. European Journal of Pain 2008, 12, 600-610, 10.1016/j.ejpain.2007.10.001.

- Janice E Sumpton; Dwight E Moulin; Fibromyalgia: Presentation and management with a focus on pharmacological treatment. Pain Research and Management 2009, 13, 477-483, 10.1155/2008/959036.

- Maurizio Rizzi; Piercarlo Sarzi-Puttini; Fabiola Atzeni; Franco Capsoni; Arnaldo Andreoli; Marica Pecis; Stefano Colombo; Mario Carrabba; Margherita Sergi; Cyclic alternating pattern: a new marker of sleep alteration in patients with fibromyalgia?. The Journal of Rheumatology 2004, 31, 1193–9.

- Margaret N. Olsen; David D. Sherry; Kathleen Boyne; Rebecca McCue; Paul R. Gallagher; Lee J. Brooks; Relationship between Sleep and Pain in Adolescents with Juvenile Primary Fibromyalgia Syndrome. Sleep 2013, 36, 509-516, 10.5665/sleep.2534.

- Maren L. Mahowald; Mark W. Mahowald; Nighttime sleep and daytime functioning (sleepiness and fatigue) in less well-defined chronic rheumatic diseases with particular reference to the ‘alpha-delta NREM sleep anomaly’. Sleep Medicine 2000, 1, 195-207, 10.1016/s1389-9457(00)00028-9.

- Carol A. Landis; Martha J Lentz; Joyce Tsuji; Joan L. Shaver; Dedra Buchwald; Pain, psychological variables, sleep quality, and natural killer cell activity in midlife women with and without fibromyalgia ?. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity 2004, 18, 304-313, 10.1016/s0889-1591(03)00205-8.

- José Luis Besteiro González; Tomás Vicente Suárez Fernández; Luis Arboleya Rodríguez; José Muñiz; Serafín Lemos-Giráldez; Angel Alvarez Fernández; Sleep architecture in patients with fibromyalgia.. Psicothema 2011, 23, 368–73.

- Ronald D. Chervin; Mihaela Teodorescu; Ramesh Kushwaha; Andrea M. Deline; Christine B. Brucksch; Christine Ribbens-Grimm; Deborah L. Ruzicka; Phyllis K. Stein; Daniel J. Clauw; Leslie J. Crofford; et al. Objective measures of disordered sleep in fibromyalgia.. The Journal of Rheumatology 2009, 36, 2009-16, 10.3899/jrheum.090051.

- Suely Roizenblatt; Nilton Salles Rosa Neto; Sergio Tufik; Sleep Disorders and Fibromyalgia. Current Pain and Headache Reports 2011, 15, 347-357, 10.1007/s11916-011-0213-3.

- Yves Dauvilliers; J Touchon; Le sommeil du fibromyalgique : revue des données cliniques et polygraphiques. Neurophysiologie Clinique/Clinical Neurophysiology 2001, 31, 18-33, 10.1016/s0987-7053(00)00240-9.

- Gul Mete Civelek; Pinar Oztop Ciftkaya; Metin Karatas; Evaluation of restless legs syndrome in fibromyalgia syndrome: An analysis of quality of sleep and life. Journal of Back and Musculoskeletal Rehabilitation 2014, 27, 537-544, 10.3233/bmr-140478.

- Glenn Affleck; Susan Urrows; Howard Tennen; Pamela Higgins; Micha Abeles; Sequential daily relations of sleep, pain intensity, and attention to pain among women with fibromyalgia. Pain 1996, 68, 363-368, 10.1016/s0304-3959(96)03226-5.

- Rita F. D'aoust; Alicia Gill Rossiter; Amanda Elliott; Ming Ji; Cecile Lengacher; Maureen Groer; Women Veterans, a Population at Risk for Fibromyalgia: The Associations Between Fibromyalgia, Symptoms, and Quality of Life. Military Medicine 2017, 182, e1828-e1835, 10.7205/MILMED-D-15-00557.

- Akifumi Kishi; Benjamin H. Natelson; Fumiharu Togo; Zbigniew R. Struzik; David M. Rapoport; Yoshiharu Yamamoto; Sleep stage transitions in chronic fatigue syndrome patients with or without fibromyalgia. 2010 Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology 2010, 2010, 5391-5394, 10.1109/iembs.2010.5626478.

- Nancy A. Hamilton; Delwyn Catley; Cynthia Karlson; Sleep and the affective response to stress and pain.. Health Psychology 2007, 26, 288-295, 10.1037/0278-6133.26.3.288.

- Julius H. Bourke; Fibromyalgia and Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: Management Issues. Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry in Japan 2015, 34, 78-91, 10.1159/000369087.

- Su‐Chen Fang; Yu‐Lin Wu; Shih‐Ching Chen; Hao‐Wen Teng; Pei-Shan Tsai; Subjective sleep quality as a mediator in the relationship between pain severity and sustained attention performance in patients with fibromyalgia. Journal of Sleep Research 2019, 28, e12843, 10.1111/jsr.12843.

- Lesley M. Arnold; Leslie J. Crofford; Philip J. Mease; Somali Misra Burgess; Susan C. Palmer; Linda Abetz; Susan A. Martin; Patient perspectives on the impact of fibromyalgia. Patient Education and Counseling 2008, 73, 114-120, 10.1016/j.pec.2008.06.005.

- Kati Thieme; Dennis C. Turk; Herta Flor; Comorbid Depression and Anxiety in Fibromyalgia Syndrome: Relationship to Somatic and Psychosocial Variables. Psychosomatic Medicine 2004, 66, 837-844, 10.1097/01.psy.0000146329.63158.40.

- Hans M. Nordahl; Tore C. Stiles; Personality styles in patients with fibromyalgia, major depression and healthy controls. Annals of General Psychiatry 2007, 6, 9-9, 10.1186/1744-859X-6-9.

- Carmen M. Galvez Sánchez; Casandra Montoro; Stefan Duschek; Gustavo A. Reyes Del Paso; Pain catastrophizing mediates the negative influence of pain and trait-anxiety on health-related quality of life in fibromyalgia. Quality of Life Research 2020, 29, 1871-1881, 10.1007/s11136-020-02457-x.

- Jeong-Won Lee; Kyung-Eun Lee; Dong-Jin Park; Seong-Ho Kim; Seong-Su Nah; Ji Hyun Lee; Seong-Kyu Kim; Yeon-Ah Lee; Seung-Jae Hong; Hyun-Sook Kim; et al.Hye-Soon LeeHyoun Ah KimChung-Il JoungSang-Hyon KimShin‐Seok Lee Determinants of quality of life in patients with fibromyalgia: A structural equation modeling approach. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0171186, 10.1371/journal.pone.0171186.

- González, E., Elorza, J., Failde, I.; Comorbilidad psiquiátrica y Fibromialgia. Su efecto sobre la calidad de vida de los pacientes. Actas Esp Psiquiatr 2010, 38, 295–300.

- Jaiberth Antonio Cardona-Arias; Vanessa León-Mira; Alejandro Antonio Cardona-Tapias; Calidad de vida relacionada con la salud en adultos con fibromialgia, 2012. Revista Colombiana de Reumatología 2013, 20, 19-29, 10.1016/s0121-8123(13)70009-4.

- Dagmar Keller; Manuel De Gracia; Ramón Cladellas; [Subtypes of patients with fibromyalgia, psychopathological characteristics and quality of life].. Actas espanolas de psiquiatria 2011, 39, 273–279.

- M. Capraro; M. Della Valle; M. Podswiadek; P. De Sandre; E. Sgnaolin; R. Ferrari; The role of illness perception and emotions on quality of life in fibromyalgia compared with other chronic pain conditions. Reumatismo 2012, 64, 142–150, 10.4081/reumatismo.2012.142.

- Alberto Soriano-Maldonado; Kirstine Amris; Francisco B. Ortega; Víctor Segura-Jiménez; Fernando Estévez-López; Inmaculada C. Álvarez-Gallardo; Virginia A. Aparicio; Manuel Delgado-Fernández; Marius Henriksen; Jonatan R. Ruiz; et al. Association of different levels of depressive symptoms with symptomatology, overall disease severity, and quality of life in women with fibromyalgia. Quality of Life Research 2015, 24, 2951-2957, 10.1007/s11136-015-1045-0.

- R Celiker; P Borman; F Oktem; Y Gökçe-Kutsal; O Başgöze; Psychological disturbance in fibromyalgia: relation to pain severity.. Clinical Rheumatology 1997, 16, 179–84.

- Karin B Jensen; Frank Petzke; Serena Carville; Peter Fransson; Hanke Marcus; Steven Williams; Ernest Choy; Yves Mainguy; Richard Gracely; Martin Ingvar; et al.Eva Kosek Anxiety and depressive symptoms in fibromyalgia are related to poor perception of health but not to pain sensitivity or cerebral processing of pain. Arthritis Care & Research 2010, 62, 3488-3495, 10.1002/art.27649.

- N Kurtze; Kjell Terje Gundersen; Sven Svebak; The role of anxiety and depression in fatigue and patterns of pain among subgroups of fibromyalgia patients.. British Journal of Medical Psychology 1998, 71, 185-194, 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1998.tb01379.x.

- N Kurtze; Sven Svebak; Fatigue and patterns of pain in fibromyalgia: correlations with anxiety, depression and co-morbidity in a female county sample.. British Journal of Medical Psychology 2001, 74, 523-537, 10.1348/000711201161163.

- M. Lange; F. Petermann; Einfluss von Depression auf das Fibromyalgiesyndrom. Der Schmerz 2010, 24, 326-333, 10.1007/s00482-010-0937-8.

- Riccardo Torta; Francesco Pennazio; V. Ieraci; Anxiety and depression in rheumatologic diseases: the relevance of diagnosis and management.. Reumatismo 2014, 66, 92-97, 10.4081/reumatismo.2014.769.

- Serge Perrot; Eric Vicaut; Dominique Servant; P Ravaud; Prevalence of fibromyalgia in France: a multi-step study research combining national screening and clinical confirmation: The DEFI study (Determination of Epidemiology of FIbromyalgia). BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders 2011, 12, 224-224, 10.1186/1471-2474-12-224.

- David Watson; James W. Pennebaker; Health complaints, stress, and distress: Exploring the central role of negative affectivity.. Psychological Review 1989, 96, 234-254, 10.1037/0033-295x.96.2.234.

- Tamar Bar On –Kalfon; Gilad Gal; Ran Shorer; Jacob Ablin; Cognitive functioning in fibromyalgia: The central role of effort. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 2016, 87, 30-36, 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2016.06.004.

- Bruce Dick; Michelle J. Verrier; Troy K. Harker; Saifudin Rashiq; K. Troy Harker; Disruption of cognitive function in Fibromyalgia Syndrome☆. Pain 2008, 139, 610-616, 10.1016/j.pain.2008.06.017.

- Stefan Duschek; Natalie S. Werner; Andreas Winkelmann; Sarah Wankner; Implicit Memory Function in Fibromyalgia Syndrome. Behavioral Medicine 2013, 39, 11-16, 10.1080/08964289.2012.708684.

- Gustavo A. Reyes Del Paso; Pablo De La Coba; María Martín‐Vázquez; Julian F. Thayer; Time domain measurement of the vascular and myocardial branches of the baroreflex: A study in physically active versus sedentary individuals. Psychophysiology 2017, 54, 1528-1540, 10.1111/psyp.12898.

- Carmen M. Galvez-Sánchez; Gustavo A. Reyes Del Paso; Stefan Duschek; Cognitive Impairments in Fibromyalgia Syndrome: Associations With Positive and Negative Affect, Alexithymia, Pain Catastrophizing and Self-Esteem. Frontiers in Psychology 2018, 9, 377, 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00377.

- Barbara J. Cherry; Laura Zettel-Watson; Renee Shimizu; Ian Roberson; Dana N. Rutledge; Caroline J. Jones; Cognitive Performance in Women Aged 50 Years and Older With and Without Fibromyalgia. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 2012, 69, 199-208, 10.1093/geronb/gbs122.

- Dieuwke S. Veldhuijzen; Stephanie F.V. Sondaal; Joukje M. Oosterman; Intact Cognitive Inhibition in Patients With Fibromyalgia but Evidence of Declined Processing Speed. The Journal of Pain 2012, 13, 507-515, 10.1016/j.jpain.2012.02.011.

- Robert M. Bennett; Ronald Friend; Kim D. Jones; Rachel Ward; Bobby Kwanghoon Han; Rebecca L Ross; The Revised Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQR): validation and psychometric properties. Arthritis Research & Therapy 2009, 11, R120-R120, 10.1186/ar2783.

- Denise C. Park; Jennifer M. Glass; Meredith Minear; Leslie J. Crofford; Cognitive function in fibromyalgia patients. Arthritis Care & Research 2001, 44, 2125-2133, 10.1002/1529-0131(200109)44:9<2125::aid-art365>3.0.co;2-1.

- Frank Leavitt; Robert S. Katz; Speed of Mental Operations in Fibromyalgia. JCR: Journal of Clinical Rheumatology 2008, 14, 214–218, 10.1097/rhu.0b013e31817a2472.

- Antonio Verdejo-García; Francisca López ‐Torrecillas; E P Calandre; Antonia Delgado-Rodríguez; Antoine Bechara; Executive Function and Decision-Making in Women with Fibromyalgia. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology 2009, 24, 113-122, 10.1093/arclin/acp014.

- Cristina Muñoz Ladrón De Guevara; María José Fernández-Serrano; Gustavo A. Reyes Del Paso; Stefan Duschek; Executive function impairments in fibromyalgia syndrome: Relevance of clinical variables and body mass index. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0196329, 10.1371/journal.pone.0196329.

- César Walteros; Juan P. Sánchez-Navarro; Miguel A. Muñoz; José M. Martínez-Selva; D. R. Chialvo; Pedro Montoya; Altered associative learning and emotional decision making in fibromyalgia. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 2011, 70, 294-301, 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2010.07.013.

- Olga Gelonch; Maite Garolera; Joan Valls; Lluís Rosselló; Josep Pifarré; Executive function in fibromyalgia: Comparing subjective and objective measures. Comprehensive Psychiatry 2016, 66, 113-122, 10.1016/j.comppsych.2016.01.002.

- David A Williams; Daniel Clauw; Jennifer M. Glass; Perceived Cognitive Dysfunction in Fibromyalgia Syndrome. Journal of Musculoskeletal Pain 2011, 19, 66-75, 10.3109/10582452.2011.558989.

- Diego Munguía-Izquierdo; Alejandro Legaz Arrese; Diego Moliner-Urdiales; Joaquín Reverter-Masia; [Neuropsychological performance in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome: relation to pain and anxiety].. Psicothema 2008, 20, 427–431.

- Sarah Weiß; Andreas Winkelmann; Stefan Duschek; Recognition of Facially Expressed Emotions in Patients with Fibromyalgia Syndrome. Behavioral Medicine 2013, 39, 146-154, 10.1080/08964289.2013.818932.

- Sofia Martinsen; Pär Flodin; Jonathan Berrebi; Monika Löfgren; Indre Bileviciute-Ljungar; Martin Ingvar; Peter Fransson; Eva Kosek; Fibromyalgia Patients Had Normal Distraction Related Pain Inhibition but Cognitive Impairment Reflected in Caudate Nucleus and Hippocampus during the Stroop Color Word Test. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e108637, 10.1371/journal.pone.0108637.

- I. Coppieters; Kelly Ickmans; Barbara Cagnie; Jo Nijs; R. De Pauw; Suzie Noten; Mira Meeus; Cognitive Performance Is Related to Central Sensitization and Health-related Quality of Life in Patients with Chronic Whiplash-Associated Disorders and Fibromyalgia.. May 2017 2015, 18, 389-401.

- K. Ickmans; Mira Meeus; M. De Kooning; L. Lambrecht; N. Pattyn; J. Nijs; Associations between cognitive performance and pain in chronic fatigue syndrome: comorbidity with fibromyalgia does matter. Physiotherapy 2015, 101, e635-e636, 10.1016/j.physio.2015.03.3465.

- Susanne Becker; Dieter Kleinböhl; Dagmar Baus; Rupert Hölzl; Operant learning of perceptual sensitization and habituation is impaired in fibromyalgia patients with and without irritable bowel syndrome. Pain 2011, 152, 1408-1417, 10.1016/j.pain.2011.02.027.

- Bennett, R. M. . Neurologic features in fibromialgia. In Fibromyalgia and other central syndromes ; D. J. Wallace y D. J. Clauw., Eds.; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.: Philadelphia, 2005; pp. 133-143.

- Wallace, D. J.. Genitourinary associations in Fibromyalgia. In Fibromyalgia and other central syndromes.; D. J. Wallace y D. J. Clauw., Eds.; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, 2005; pp. 235-239.

- Ramesh Balasubramaniam; Reny De Leeuw; Hua Zhu; Robert B. Nickerson; Jeffrey P. Okeson; Charles R. Carlson; Prevalence of temporomandibular disorders in fibromyalgia and failed back syndrome patients: A blinded prospective comparison study. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology, and Endodontology 2007, 104, 204-216, 10.1016/j.tripleo.2007.01.012.

- Yunus, M. B.. Symptoms and signs of Fibromyalgia syndrome: an overview. In Fibromyalgia and other central syndromes. ; D. J. Wallace y D. J. Clauw. , Eds.; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.: Philadelphia, 2005; pp. 125-132.

- Jayde E. Kurland; Walter J. Coyle; Anne Winkler; Elizabeth Zable; Prevalence of Irritable Bowel Syndrome and Depression in Fibromyalgia. Digestive Diseases and Sciences 2006, 51, 454-460, 10.1007/s10620-006-3154-7.

- P. De Roa; P. Paris; J. L. Poindessous; O. Maillet; Anne Héron; Subjective Experiences and Sensitivities in Women with Fibromyalgia: A Quantitative and Comparative Study. Pain Research and Management 2018, 2018, 1-8, 10.1155/2018/8269564.

- V Aykut; A Elbay; I Çigdem Uçar; F Esen; A Durmuş; Remzi Karadag; H Oguz; Corneal sensitivity and subjective complaints of ocular pain in patients with fibromyalgia. Eye 2018, 32, 763-767, 10.1038/eye.2017.275.

- Zeliha Kapusuz; Özlem Balbaloğlu; Mahmut Özkiriş; Levent Saydam; Does fibromyalgia have an effect on hearing loss in women?. TURKISH JOURNAL OF MEDICAL SCIENCES 2017, 47, 1699-1702, 10.3906/sag-1511-25.

- Akiko Okifuji; Dennis C. Turk; Stress and psychophysiological dysregulation in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome.. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback 2002, 27, 129-141, 10.1023/a:1016243710507.

- Siv Söderberg; Berit Lundman; TRANSITIONS EXPERIENCED BY WOMEN WITH FIBROMYALGIA. Health Care for Women International 2001, 22, 617-631, 10.1080/073993301753235389.

- Alex J Zautra; Robert Fasman; Brendt P. Parish; Mary C. Davis; Daily fatigue in women with osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and fibromyalgia. Pain 2007, 128, 128-135, 10.1016/j.pain.2006.09.004.

- Akiko Okifuji; David H. Bradshaw; Gary W. Donaldson; Dennis C. Turk; Sequential Analyses of Daily Symptoms in Women With Fibromyalgia Syndrome. The Journal of Pain 2011, 12, 84-93, 10.1016/j.jpain.2010.05.003.

- Ercolie R. Bossema; Henriët Van Middendorp; Johannes W. G. Jacobs; Johannes W. J. Bijlsma; Rinie Geenen; Influence of Weather on Daily Symptoms of Pain and Fatigue in Female Patients With Fibromyalgia: A Multilevel Regression Analysis. Arthritis Care & Research 2013, 65, 1019-1025, 10.1002/acr.22008.

- Loren L. Toussaint; Ann Vincent; Samantha J. McAllister; Terry H. Oh; Afton L. Hassett; A comparison of fibromyalgia symptoms in patients with Healthy versus Depressive, Low and Reactive affect balance styles. Scandinavian Journal of Pain 2014, 5, 161-166, 10.1016/j.sjpain.2014.05.001.

- P Andrã©Ll; T Schultz; Kaisa Mannerkorpi; L Nordeman; M Bã¶rjesson; C Mannheimer; Health-related quality of life in fibromyalgia and refractory angina pectoris: A comparison between two chronic non-malignant pain disorders. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine 2014, 46, 341-347, 10.2340/16501977-1279.

- William Karper; Effects of exercise, patient education, and resource support on women with fibromyalgia: An extended long-term study. Journal of Women & Aging 2016, 28, 555-562, 10.1080/08952841.2016.1223954.

- Rodrigo Pegado; Sandra Cristina De Andrade; Maria Helena Constantino Spyrides; Maria Thereza Albuquerque Barbosa Cabral Micussi; Maria Bernardete Cordeiro De Sousa; Impacts of social support on symptoms in Brazilian women with fibromyalgia. Revista Brasileira de Reumatologia (English Edition) 2017, 57, 197-203, 10.1016/j.rbre.2016.07.001.

- Otis, J.D. . Managing chronic pain. A cognitive-behavioral therapy approach. ; Barron, B.A., Eds.; Oxford University Press, Inc : New York, 2007; pp. 113.

- Kanner, R.. Secretos en el tratamiento del dolor. ; McGraw-Hill Interamericana: México, D. F, 2006; pp. 1009.

- Wall, P., Melzack, R.. Tratado del Dolor. (5ta Ed). ; Stephen McMahon Martin Koltzenburg, Eds.; Elsevier : España, 2006; pp. 1270.

- Patient-Reported Outcomes. . National Quality Forum. . Retrieved 2020-9-3