Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Annalisa Barbieri and Version 3 by Jessie Wu.

It is well known the connection between the eye and the brain due to the optic nerve, so that, the retina is considered the window of the brain. Therefore the interconnection between neurodegenerative ocular diseases [i.e. glaucoma, Age-related Macular Degeneration (AMD), diabetic retinopathy, retinitis pigmentosa] and neurodegenerative pathologies of the central nervous system (CNS) (i.e. Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease) are also defined.

- eye

- SNC

- retinal neurodegeneration

- neurodegenerative diseases

1. Ocular Neurodegenerative Diseases

1.1. Glaucoma

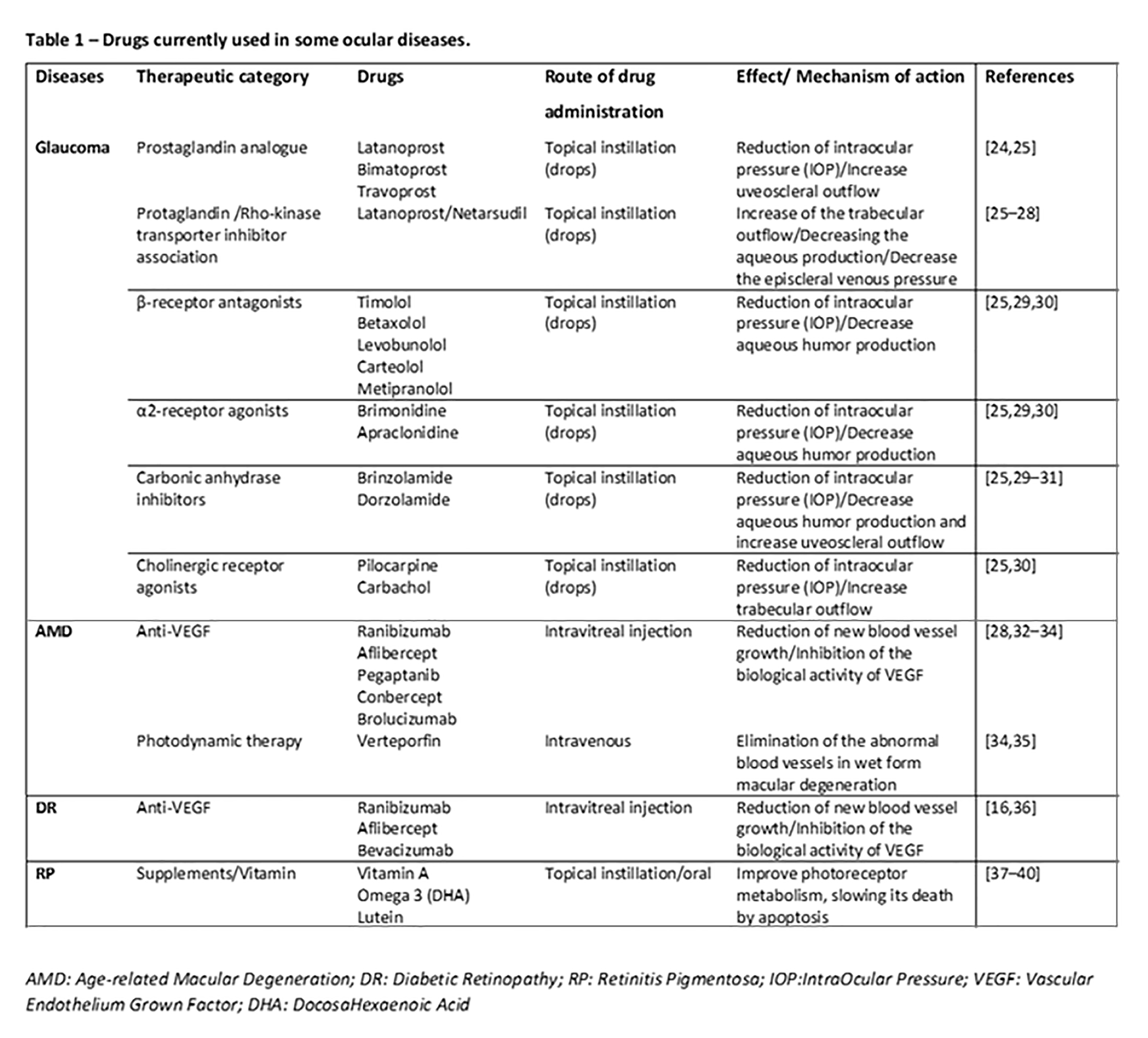

Glaucoma is currently one of the most common causes of irreversible visual impairment and blindness in the world [1][80]; it includes a group of heterogeneous eye diseases, with closed-angle glaucoma and open-angle glaucoma the two main types. Generally, glaucoma is due to the increase in the internal pressure of the eye, that is, the intraocular pressure (IOP), which irreparably damages neurons; in some cases the reduction of the blood supply to the optic nerve, which cause loss of visual field, is involved [2][3][54,81]. In recent years, the literature argues in favor of the fact that glaucoma is a widespread neurodegenerative disease involving the CNS, as the correlation is strong between the dysfunction and death of CNS neurons with retinal ones. Moreover, neurodegenerative pathways that contribute to transynaptic neurodegeneration in AD, as well as in other CNS diseases, might also be similar to those in neurodegeneration correlated to glaucoma [4][5][11,82]. Retinal ganglion cell damage is a characteristic of both glaucoma and AD, along with discovery of amyloid-beta and tau protein deposition, known to be pathognomonic of AD, in the retina and aqueous humor of the eye [6][58]. In particular, primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG), the most common type, is characterized by slow, progressive, degeneration of retinal ganglion cells and their axons in the optic nerve, leading to visual field defects [7][83]. Intraocular pressure (IOP) is considered a major risk factor for the development of POAG, and the modified optic nerve head is the site of initial damage. However, elevated IOP is not present in all types of POAG, and in normal-tension glaucoma IOP is not elevated, so other risk factors are likely involved in the optic neuropathy. Literature evidence provides that the pressure and composition of the cerebro-spinal fluid (CSF) surrounding the optic nerve may have critical involvement in the pathogenesis of glaucoma [7][83]. In this regard, the presence of the glymphatic system was described. This particular system is a brain-wide paravascular pathway for CSF–interstitial fluid exchange that facilitates clearance of interstitial solutes, including amyloid-beta, from the brain. If the glymphatic system does not operate properly, amyloid-beta brain accumulation occurs in AD. In the same way, the glymphatic system may also have potential clinical relevance for the understanding of glaucoma. Aβ accumulation may be implicated in the development of retinal ganglionic cells’ apoptosis. Recent studies indicated that accumulation of amyloid-beta, which is associated with the progression of Alzheimer disease, may also be responsible for retinal ganglion cell death in glaucoma, so the neurodegenerative processes in glaucoma could share, at least in part, a common mechanism with Alzheimer disease [7][83]. Interestingly, literature data, although derived from animal studies, found time-dependent expressions and localization of Aβ in the retina as well as in the optic nerve head after chronic IOP increase seen in glaucoma [8][84]. Moreover, nowadays, it is well established that glaucoma leads to ganglion cell death through several other mechanisms including oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, and mitochondrial dysfunction [9][10][85,86]. Retinal ganglion cells and optic nerve fibers are particularly rich in mitochondria, necessary organelles to produce energy for nerve conduction. The reduction in energy production and the increase in the production of free radicals at the mitochondrial level are to be considered as potential additional mechanisms in the etiopathogenesis of glaucoma. Definitely, the identification of cellular mechanisms and molecular pathways related to retinal ganglion cell death is the first step toward the discovery of new therapeutic strategies to control glaucoma [11][12][87,88].

1.2. Age-Related Macular Degeneration

Age-related Macular Degeneration (AMD) is an ocular pathology that involves the central area of the retina, the so-called macula, causing an irreversible reduction in distinct vision, and it is one of the leading causes of blindness in developed countries. AMD is classified into a dry form, with about 80% of incidence in the population affected, and a wet form or neovascular form, with about 20% of incidence. In particular, in dry age-related macular degeneration, characteristic lesions, called drusen, appear. These are accumulations of cellular waste that can be reabsorbed or calcified. In wet macular degeneration, in addition to drusen, there is the anomalous formation of new vessels under the retina, responsible for the exudative evolution of macular degeneration [13][14][89,90]. Therefore, localized sclerosis under the retina, the accumulation of lipids, and alterations in the metabolism of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) contribute to the macular degenerative process [15][91]. Under these conditions, the physiological metabolism of the retina is prevented. Moreover, retinal hypoxia may induce an upregulation of VEGF by the RPE and thus promote the growth of abnormal vessels from choroid, with VEGF being the main factor related to ocular neovascularization [16][17][92,93]. Furthermore, the RPE is crucial for the maintenance of photoreceptor cells as it promotes a physiological vascular environment. In particular, RPE keeps retinal nerve tissue healthy by secreting hormones, transporting molecules, eliminating dead cells, and modulating immune factors. The RPE is responsible for the transport of nutrients, ions, and water. It absorbs light and protects the retina from photooxidation; in addition, it is responsible for stabilizing the concentration of ions in the subretinal space to keep the photoreceptors excitable. To maintain RPE homeostasis and function, a particular molecular network is necessary, with microRNAs being indispensable components [18][94].

With aging, several modifications occur in the RPE cells as a result of their altered capacity for removing residual substances, leading to a further damage in the pathogenesis of AMD. The main risk factor for AMD is age, but family history, female sex, smoking, and high blood pressure can somehow contribute; among these, several studies suggest that smoking is the main oxidative stress factor [19][20]. Nevertheless, different oxidative damage, such as light exposure or inflammation that affect the retina, has been strongly linked with AMD [20][37]. Globally considered together, oxidative stress and mitochondrial damage in the retinal pigment epithelium may play an important role in the pathogenesis of age-related macular degeneration [21][95]. It is well known that mitochondrial dysfunction has been associated with aging, as well as with several age-related diseases, such as Alzheimer and Parkinson diseases, suggesting that ocular and CNS neuropathologies share more than one biochemical mechanism. Moreover, AMD also is associated with non-visual impairment such as phonemic verbal fluency, verbal memory, establishment of cognitive decline during life, and higher risk of dementia [22][23][13,96]. Once again, it is emphasized how cognitive impairment, as well as visual impairment, is common and superimposed among older adults.

1.3. Diabetic Retinopathy

Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is a complication of diabetes that affects the eyes, causing severe visual impairment. It is induced by damage to the blood vessels in the light-sensitive part of the eye, the retina, with the vasculopathy being the main involved pathophysiologic mechanism [24][15]. It can develop in subjects affected by both type 1 and type 2 diabetes. There are two types of retinopathies. The first is the early diabetic retinopathy, also known as nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy (NPDR). As the disease progresses, the walls of the blood vessels weaken and are subject to microaneurysms, small swellings that, when damaged, lead to bleeding. Then there is the risk of an accumulation of fluids, i.e., formation of edema, in the macula, which cause reduced vision. The second type is proliferative or advanced diabetic retinopathy (PDR). It is the most serious type because it coincides with the abnormal growth of new blood vessels damaging the retina. Diabetes is, in fact, associated with a growth of weak blood vessels, more prone to rupture, or smaller vessels, and this leads to a lower oxygen transport capacity to the retinal tissues. As a result, new vessels are stimulated by the formation of ischemic areas in the retina. In fact, retinal microvascular disease is an early compromission, induced by low-grade, persistent leukocyte activation, which causes repeated episodes of capillary occlusion and progressive retinal ischemia [25][97]. This situation can induce detachment of the retina or an abnormal flow of fluid into the eye, causing glaucoma. The underlying molecular mechanisms associated with vascular dysfunction, especially endothelial dysfunction, in DR are multifactorial. Chronic inflammation, oxidative stress, leukostasis, dysregulated growth factors and cytokines, and disruption of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ are mainly involved [26][98]. Diabetic retinopathy is prevalent in around 35% of patients with diabetes. The disease progresses slowly, causing damages that become progressively irreversible. Unfortunately, treatment options are limited. As therapeutic approaches, photocoagulation of the ischemic areas of the retina to stabilized blood vessels, intravitreal injections with VEGF-inhibitory agents or corticosteroids, and ocular surgery can be applied [27][99]. It is worth noting that anti-VEGF agents used in clinical practice, such as ranibizumab, bevacizumab, and aflibercept, are considerably different in terms of molecular interactions when they bind with VEGF [28][100]; therefore, characterization of such features can improve the design of novel biological drugs potentially useful in clinical practice. Recent findings hypothesize that retinal neurodegeneration represents a critical, early component of DR. It occurs prior to the vascular changes classically associated with DR and contributes to disease pathogenesis [29][30][101,102]. In the retina, neurons, glia, and vasculature form the blood–retinal barrier (BRB), which functions as the maintenance of energy, homeostasis, and neurotransmitter regulation. In the progression of diabetes, the BRB is damaged early and its breakdown is sustained by RPE secretion of different factors, among which the main ones are vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and proinflammatory cytokines (i.e., TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β) [31][103]. It is interesting to note that VEGF may act as a negative regulator of pericyte function, with these cells being involved in early BRB abnormalities in diabetic retinopathy [32][104]. During progression of DR, the retina is infiltrated by the above mentioned secreted factors’ cells and serum proteins, further damaging blood vessels and neurons. Moreover, in addition to vascular damage and the loss of BRB integrity, other neurodegenerative changes occur in the retina such as apoptosis, glial cell reactivity, microglial activation, and altered glutamate metabolism that could prove some of the functional deficits in vision [29][33][101,105]. Additionally, to point out the neurodegeneration, clinical evidence indicates CNS lesions in patients with diabetic retinopathy; detection of small punctate white matter lesions in the brain and cortical atrophy in some regions suggests that there is an association between retinopathy and brain tissue damage [34][106]. Other studies highlight that diabetes-induced retinal neurodegeneration and brain neurodegenerative diseases share common pathogenic pathways. Indeed, DR patients might exhibit abnormalities in the central nervous system, often showing impaired cognition and increased risks of dementia as well as Alzheimer disease [35][107].

1.4. Retinitis Pigmentosa

Retinitis pigmentosa (RP) is an inherited retinal dystrophy leading to progressive loss of the photoreceptors and retinal pigment epithelium and resulting in blindness usually after several decades [36][37][38][17,108,109]. Usually, it is bilateral, but some evidence reports of unilateral eye involvement with RP. It affects approximately one subject in 5000 worldwide, making RP one of the most common inherited diseases of the retina [39][110]. Generally, degeneration of rod photoreceptors, the cells controlling night vision, precedes and exceeds cone degeneration, as a majority of RP genetic mutations affect rods selectively. Early symptoms of retinitis pigmentosa include impaired night vision and peripheral vision [38][109]. The main clinical hallmarks consist of bone-spicule deposits, waxy optic disc, and shrinked retinal vessels. As previously pointed out, retinitis pigmentosa does not share alterations with neurodegenerative diseases of the CNS; it is linked with reduction of white matter volume in the brain, as seen in RP patients [40][19].

There is no definitive therapy. In some cases it is possible to slow down the degenerative process with strategies such as the administration of vitamins, and protection from sunlight and combined approaches, such as gene-replacement therapy, may be useful to slow photoreceptor cell death [41][42][111,112]. Different RP gene mutations are the basis of alterations in molecular mechanisms such as phototransduction cascade, vitamin A metabolism, interactive cell–cell signaling or synaptic interaction, and intron splicing of RNA [43][113]. Moreover, previous studies revealed that an insufficiency of the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) to process misfolded proteins in affected photoreceptor cells could be involved [44][114]. Impairments of UPS function in the central nervous system underlie an increasing number of genetic diseases, many of which affect the retina [45][115].