After the Neolithic domestication at specific sites, animals colonized the world and adapted to live and produce in a variety of different environments. Molecular technologies permit to scan the genome of local livestock breeds in search of adaptive genes to be used in accelerated breeding schemes to mitigate the deleterious effects of climate change on livestock welfare and productivity.

- climate change

- livestock

- adaptation

1. Introduction

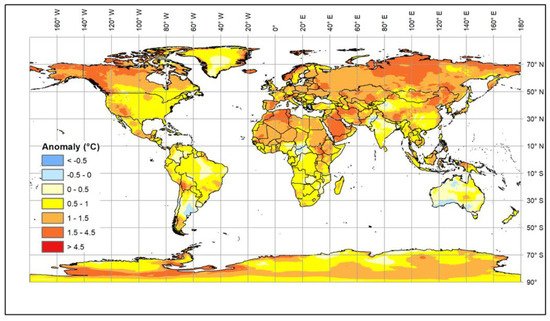

Climate change is generally causing an increase in global temperatures (see Box 1 ). The most recent estimates [1] suggest that a 1.5 °C warming compared to the 1850–1900 baseline will be reached in the second half of the current decade, but, in addition, there are longer cold periods and increased levels of solar radiation [2][3][4][5][6][2,3,4,5,6] ( Figure 1 ).

These changes affect both extensive and intensive farming systems [7][8][7,8]. The impact of environmental changes on animals affects their health, growth, and fertility as well as the diseases to which they are exposed. In addition, availability and types of feed may change because of the impact of the climate on the production and quality of grains, pasture and forage crops [9][10][9,10], which will affect nutrition as well as animal health and metabolism [11]. Livestock can adapt to gradual changes in environmental temperature. However, rapid changes or extended periods of extreme conditions reduce their welfare and productivity and are potentially life threatening. Therefore, the current rapid rise in global temperature is increasingly exposing livestock to stress in many countries. Some local breeds that have been kept in areas with adverse conditions, such as high temperature and humidity or drought, have become adapted over many generations; these breeds are an invaluable resource for research and breeding. It is urgent that we understand the biological mechanisms underlying their adaptability, and, in particular, to identify genomic regions and genes that control such mechanisms in order to facilitate the rapid selection of livestock resilient to climate change.

2. Impacts of Climate Change on Livestock

With increasing global temperatures, more productive livestock are at greater risk (see Box 2 ), because they have higher feed intake and feed consumption, which is directly related to animal heat production [12]. Animals eat less to counteract high temperatures, and nutrients are prioritized to support maintenance rather than production and reproduction. In the central U.S., for example, severe losses of beef cattle kept in feedlots have been reported because of heat waves in summer and extreme snowstorms and wind in winter [13]. Climate related economic losses as a result of animal death and reduced performance have been seen [14]. Cattle, sheep, pigs and chickens reduce their feed intake by 3–5% for each unit increase in temperature above 30 °C [15]. Reproduction is particularly affected. Hahn [16] reported that conception rates in dairy cows are reduced by 4.6% per unit change above 70 in the temperature humidity index (THI) [17]. For beef cattle kept in range or pasture management systems, a decrease in pregnancy rates of 3.2% and 3.5% was observed for each unit increase in average THI above 70 and an increase in average temperature above 23.4 °C, respectively. Among environmental variables, temperature has the greatest effect on cow pregnancy rates [18].

Climate change includes altered rainfall patterns that, combined with geographical factors, such as soil type, affect crop production [19][20][21][19,20,21]. Drought reduces biomass [22], increases lignin accumulation in plant tissues, and reduces proteins, resulting in less digestible forages [23] and insufficient energy to meet livestock requirements [24][25][24,25]. Increased occurrence of prolonged drought is therefore of great concern to pasture-based livestock systems [23], especially those in environments which cannot support arable production [26].

Climate change influences the distribution of animal pathogen vectors and parasite range [27] which, together with the decreased immune response of animals under stress (triggered by cortisol), exposes livestock to higher risks of disease. Early springs, warmer winters and changes in rainfall distribution affect the seasons in which pathogens, parasites and vectors are present, potentially increasing proliferation and survival of these organisms. Bluetongue recently spread northward from Africa to Europe [28] as a consequence of climate-driven ecosystem changes and the associated expansion of the geographic range of the insect Culicoides imicola, the vector of the virus [29]. Other vectors, such as the tick Rhipicephalus appendiculatus, which is the host for the protozoan pathogen Theileria parva, are predicted to shift their geographic range due to climate change, moving southward from central sub-Saharan Africa towards southern Africa [30]. Higher temperatures in Europe have increased parasite burdens such as helminths, with a shift from species traditionally found in temperate zones such as Ostertagia ostertagi to tropically adapted species, particularly Haemonchus contortus [31][32][31,32]. In addition to temperature, increased rainfall and humidity have affected the distribution of parasites. Leptospirosis in humans has been linked to transmission from livestock, with many outbreaks reported following extreme weather events around the world [33].

High resolution meteorological data are used to evaluate climate trends and variability and to predict the frequency of extreme events. Where meteorological data are not available, advanced climate modelling produces “Climate Reanalysis” datasets for a comprehensive description of the climate in three-dimensional grids. “Climate Reanalysis” has become an essential tool for modelling meteorological data to provide services to sectors dependent on climate assessments, forecasts and projections, including ecosystem management, agriculture, and livestock farming [34][35][34,35]. Climate modelling is also able to produce short- to long-term climate predictions (months to a few decades ahead), and projections extending over many decades at the global level.

3. Becoming Adapted

The level of heat stress experienced by an animal is the result of a combination of air temperature, relative humidity [36][71] and other climate factors including wind speed and solar radiation [37][72]. Depending on the management system, these parameters may make different contributions to the risk of thermal stress [38][73]. Environmental parameters can be measured and used to construct indices and set thresholds to define risk situations.

Most of the indices defining thermal stress risk have been developed for cattle, especially for dairy cows that are particularly susceptible to high temperatures. The Temperature Humidity Index (THI) [17] takes into account the effect of air temperature and humidity. THI was originally developed as a general indicator of heat stress for humans, but today is also applied to livestock. Over the years, the model and threshold values used to define heat stress conditions have been modified [38][73], and corrections are now applied if cooling systems are used in the housing [39][74]. THI does not take into account the cumulative effect of high temperature [38][73] or the impact of wind speed and solar radiation, which are important when estimating the level of heat stress experienced by an animal. The Equivalent Temperature Index (ETI) includes air speed in the formula [40][75], although solar radiation is not considered [38][73]. The THI adjusted (THIadj) index considers both the wind speed and the solar radiation, as well as breed and coat colour [41][76]. The Respiration Rate index (RR) is an extension of THIadj that also takes into account whether animals are in a shaded area or under the sun [42][77].

A comprehensive review of models for predicting heat stress response in livestock is given in Rashamol et al. [43][78].

Senepol cattle were developed on the island of St Croix to create a breed that was polled, easily managed and tolerant of the tropical environment by crossing red polled taurine cattle with African Zebu cattle [44][81]. Some of these cattle have very short hair and reduced follicle density, giving the phenotype referred to as “SLICK”. SLICK is controlled by a single genetic locus and carriers of the Slick variant have lower core temperature than non-SLICK contemporaries [45][82]. Interestingly, the effect of SLICK is most likely through increased sweat production rather than the decrease in hair length and density [46][83]. The SLICK variant in Senepol cattle was initially mapped to chromosome 20 [47][84], and later the causative variation was identified in the prolactin receptor gene ( PRLR ). A single base deletion in exon 10 causes a frameshift that introduces a stop codon and results in the truncation of the protein [48][85]. Other criollo cattle breeds, such as Carora and Limonero, that were brought to the Americas from Spain 500 years ago [49][86] display a similar SLICK phenotype. However, these breeds do not carry the same prolactin variant that was identified in the Senepol cattle, although a genome-wide association analysis located the causative variant in or near to PLRL . DNA sequencing of SLICK Limonero cattle revealed three variants within the prolactin receptor gene that create premature stop codons in exon 11, one of which is also found in SLICK Carora cattle [50][87]. Recently, three novel variants were discovered in the PLRL gene in six Caribbean Basin cattle breeds. All create premature stop codons and increase heat tolerance. The occurrence of mutations in the prolactin receptor in several cattle breeds that are adapted to tropical climates and that have distinct evolutionary histories is unlikely to be by chance. Indeed, prolactin levels have been shown to be involved in thermoregulation in humans [51][88], showing that certain physiological processes and specific genes can be targeted by environmental pressure. The SLICK variant has now been introgressed into other breeds, including the highly productive Holstein dairy breed, creating more heat tolerant animals [52][89].

4. Seeking Adaptive Genes

A GWAS of cattle indigenous to Benin [53][99] identified several potential candidate genes associated with stress and immune response ( PTAFR, PBMR1, ADAM, TS12 ), feed efficiency ( MEGF11, SLC16A4, CCDC117 ), and conformation and growth ( VEPH1, CNTNAP5, GYPC ). The study of cold stress in Siberian cattle breeds identified two candidate genes ( MSANTD4 and GRIA4 ) on chromosome 15, putatively involved in cold shock response and body thermoregulation [54][100]. GWAS in taurine, indicine and cross-bred cattle identified PLAG1 (BTA14), PLRL (BTA20) and MSRB3 (BTA5) as candidate genes for several traits important for adaptation to extensive tropical environments [55][101]. A GWAS of the Frizarta dairy sheep breed, which is adapted to a high relative humidity environment, identified 39 candidate genes associated with body size traits including TP53, BMPR1A, PIK3R5, RPL26, and PRKDC [56][129]. An association analysis of genotype-by-environment (GxE) interactions with growth traits in Simmental cattle showed that birth weight was affected by temperature, while altitude affected weaning and yearling weight. Genes implicated in these traits included neurotransmitters ( GABRA4 and GABRB1 ), hypoxia-induced processes ( PLA2G4B, PLA2G4E, GRIN2D, and GRIK2) and keratinization ( KRT15, KRT31, KRT32, KRT33A, KRT34, and KRT3) , all processes that play a role in physiological responses associated with adaptation to the environment [57][130].

Signatures of selection related to feed adaptation have been found in sheep using an FST approach [58][153]. Of the seventeen genes under climatic selection, nine were related to energy metabolism. The strongest selection signal was around TBC1D12, on OAR22, which plays a role in GTPase regulation. The FST approach was also applied to Siberian cattle populations in order to understand the genetic basis of adaptation to cold environments [59][154]. Results identified several genes that have been implicated in thermal adaptation in cattle, such as GRIA4 , COX17 , MAATS1 , UPK1B , IFNGR1 , DDX23 , PPT1 , THBS1 , CCL5 , ATF1 , PLA1A , PRKAG1, and NR1I2.

With regard to hot environments, Li and colleagues [60][155] investigated selection signatures of bovine heat tolerance in Dehong cattle, a Chinese indigenous zebu breed, using an F ST approach. Results indicated that genes involved in heat shock ( HSF1 ), oxidative stress response ( PLCB1 , PLCB4 ), coat colour ( RAB31 ), feed intake ( ATP8A1 , SHC3 ) and reproduction ( TP63, MAP3K13, PTPN4, PPP3CC, ADAMTSL1, SS18L1, OSBPL2, TOX, RREB1, and GRK2 ) may play a role in heat adaptation.

Pairwise comparison of genetic differentiation of sheep breeds adapted to different environments identified selection signatures in the genes MITF, FGF5, MTOR, TRHDE and TUBB3 that have been associated with high-altitude adaptation [61][156]. An FST statistic approach applied to cattle breeds reared in different environments identified several genes under positive selection for thermal tolerance [62][157]. HapFLK detected the Nebulin Related Anchoring Protein gene ( NRAP) to be under selection for adaptation to cold environments [63][158], ACSS2, ALDOC, EPAS1, EGLN1 and NUCB2 to be under selection for high-altitude adaptation in cattle [64][159], and DNAJC28, GNRH1 and MREG to be associated with heat stress adaptation in sheep [65][160].