Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by F. Xavier Medina and Version 1 by Anna Bach Faig.

A growing body of scientific evidence shows that the Mediterranean Diet (MedDiet) has a beneficial effect on obesity, metabolic syndrome (MetS), cardiovascular disease (CVD), and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). These four diseases are so inherently linked that a new umbrella term, cardiodiabesity, has been adopted to reflect their coexistence and interrelationship .

- Mediterranean Diet

- diabetes mellitus

- cardiovascular disease

- metabolic syndrome

- obesity

- cardiodiabesity

- review

- PICO

1. Introduction

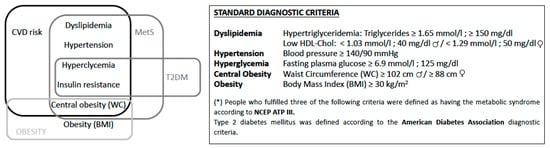

A growing body of scientific evidence shows that the Mediterranean Diet (MedDiet) has a beneficial effect on obesity, metabolic syndrome (MetS), cardiovascular disease (CVD), and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) [1,2,3,4]. These four diseases are so inherently linked that a new umbrella term, cardiodiabesity, has been adopted to reflect their coexistence and interrelationship [5,6] (Figure 1). According to the International Diabetes Federation, T2DM is expected to become the seventh leading cause of death by 2030 [7]. One of the main causes of T2DM is obesity, which is now a worldwide epidemic despite efforts by the World Health Organization (WHO) to meet the target of a 25% relative reduction in premature mortality from non-communicable diseases [7]. If the current trend continues, by 2025, approximately 18% of men and over 21% of women will be obese, up from the current rates of 10.8% and 14.9%, respectively [8]. The potential rise in the global incidence of cardiodiabesity is alarming, as central obesity and visceral adiposity have already been identified as causative agents of T2DM and CVD [8].

Figure 1. Summary of cardiodiabesity and standard diagnostic criteria. Cardiodiabesity encompasses cardiovascular disease (CVD), type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), metabolic syndrome (MetS), and obesity. Note: Reproduced with permission from García-Fernández et al. [6]. Abbreviations not previously defined: HDL-Chol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

The word diet comes from the original Greek term diaita (way of living), and the MedDiet [9]—describing traditional dietary and lifestyle habits in the Mediterranean region—has attracted international interest as a healthy, prudent dietary pattern [10] that can, as shown by extensive evidence, contribute to the prevention of chronic diseases [11].

Dietary recommendations can play an important role in the prevention of certain diseases. Not all physicians, however, are willing to offer nutritional advice, as they feel that they lack the necessary knowledge to confidently discuss these issues with their patients [12]. The main reasons for this reluctance include a lack of time or information, the need for cultural adaptations to dietary patterns and guidelines, and the complexity and contradictions of existing recommendations [13,14,15]. Even physicians themselves do not have high levels of MedDiet adherence, probably due in part to away-from-home eating, which is associated with poor health outcomes [15]. Health professionals could benefit from clinical practice guidelines (CPGs), which have been defined as recommendations developed systematically to help professionals and patients make decisions about the most appropriate health care and to select the diagnostic or therapeutic options that are best suited to addressing a health problem or a specific clinical condition [15].

According to the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation (AGREE) tool, the first step in drawing up CPGs is to define a clear set of clinical questions (CQs) using the Patient, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcome (PICO) criteria [16,17,18].

2. Current Insights on Mediterranean Diet and Cardiodiabesity

The MedDiet is a well-known, prudent dietary pattern with health benefits supported by an exponentially increasing wealth of scientific evidence. Based on the most recent and accurate scientific evidence available, the aim of this entry was to shed light on the therapeutic and preventive effects of the MedDiet on diseases encompassed by the umbrella term cardiodiabesity, in order to inform and guide the development of CPGs for physicians and health professionals. The entry addressed five CQs containing key PICO components. The evidence for CQ 1 on the association between the MedDiet and improved health in overweight and obese individuals indicates that it is precisely this population that would benefit the most from the weight loss associated with the MedDiet, and from the additional benefits of a lower risk of CVD incidence and mortality. The evidence for CQ 2, regarding the potential effects of the MedDiet on T2DM incidence and prevention, was moderate. Although some studies provided solid evidence of an effect [40,41,42,43], there were discrepancies in relation to the impact of high MedDiet adherence on the risk of T2DM in healthy individuals, and to the reduction of symptoms in those who already had the disease. However, it should be noted that fewer studies have been conducted on the effect of the MedDiet—either through an intervention or simply by measuring adherence to it—on T2DM prevention or amelioration than on other cardiodiabesity outcomes. The evidence for CQ 3, on the association between the MedDiet and MetS, showed that, overall, high adherence was related to decreased risk factors for MetS. The level of evidence was moderate-to-high, although only two studies provided clear evidence of a protective effect in MetS patients. The findings relating to the risk of MetS in healthy individuals were conflicting. The answers to CQ 1 and CQ 4 indicated that overweight and obese individuals who adhered to the MedDiet were most likely to benefit from CVD prevention and disease course modulation. A reduction in CVD incidence and mortality was observed for high-risk individuals and the general population. Considering that CVD is one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality in Western countries, a medium-term reduction in its incidence would be one of the main benefits of promoting MedDiet adherence. CQ 5 addressed the effect of the MedDiet on weight in non-overweight and non-obese individuals. The resulting evidence, graded as moderate-to-high, indicated an inverse relationship between MedDiet adherence and an increase in weight, BMI, and WC.

The evidence used to answer the five CQs was found in 50 articles from the scientific and medical literature on the association between the MedDiet and cardiodiabesity. Twenty of the articles were new and 30 were from the previous review on this topic [6], which found strong evidence of the beneficial effects of MedDiet adherence in patients with CVD, T2DM, MetS, and obesity [6]. From the 37 articles included in the previous paper [6], seven were excluded as they did not meet the inclusion criteria defined in this analysis. Taken together, the 50 articles show strong evidence that the MedDiet plays therapeutic and preventive roles in cardiodiabesity. There was a high level of evidence showing that MedDiet adherence improves the health of overweight and obese patients by reducing weight and WC, and lowering CVD incidence and mortality [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39]. Moderate evidence of a preventive effect of the MedDiet on T2DM was found for patients with the disease, and in individuals with and without risk factors [40,41,42,43,44,45,46]. Evidence of the preventive and therapeutic roles of MedDiet adherence was moderate-to-high for MetS [24,47,48,49,50,51,52] and high for CVD risk. Individuals with risk factors and the general population benefited from a reduction in CVD incidence and mortality [28,30,31,32,33,35,36,37,38,39,53,54,55,56,57,58,59], thus supporting previous meta-analysis findings [57]. The association between MedDiet adherence and low weight gain, BMI, and WC in non-obese individuals was supported by low-to-high evidence [49,50,60,61,62,63,64]. Many mechanisms underlying the beneficial effects of the MedDiet have been described elsewhere and are mainly related to improvements in lipid profile, oxidative stress, inflammation status, glucose metabolism, vascular integrity, and effects on hormone status and gut microbiota-mediated metabolic health, amongst others [4].

Regarding its beneficial effects on cardiovascular health, higher MedDiet adherence has been shown to improve complex processes relating to atherosclerosis, such as the atherogenicity of LDLs or the functionality of HDLs. In the latter case, this is particularly so when the MedDiet is supplemented with virgin olive oil. Epidemiological trials from the 1960s suggested that MedDiet adherence was associated with decreased rates of CVD. Many studies have demonstrated a mortality benefit from a Mediterranean or Mediterranean-like diet after MI. One example is the Lyon Diet Heart Study [67], which showed that a MedDiet reduced recurrent cardiovascular events by 50%–70% among MI patients. However, the role of the MedDiet in the primary prevention of CVD had not been well established until the PREDIMED trial. That trial randomized 7447 Spanish patients at high risk for CVD to one of three diets: (1) A MedDiet supplemented with extra-virgin olive oil; (2) a MedDiet supplemented with nuts; or (3) a control diet encouraging the intake of low-fat foodstuffs [26]. In both MedDiet groups, there was a statistically significant reduction in the rate of the composite primary outcome of MI, stroke, or cardiovascular death after more than four years. Regarding the strength of the association, there was a 30% absolute reduction in the incidence of major CVD events in the MedDiet groups. These findings were consistent with the previous large body of observational scientific evidence, and potential confounders as alternative explanations were discarded. A dose–response gradient was observed, whereby greater MedDiet adherence showed increased protection. Every two-point increase in adherence was associated with a 25% reduction in CVD. The results were consistent with the known facts and accepted paradigms for the natural history and biology of CVD. The beneficial effects on surrogate markers of CVD risk added to the consistency. The epidemiological evidence of low CHD rates in Mediterranean countries also supports a protective effect of the MedDiet. Regarding experimental evidence, the PREDIMED RCT was intensively scrutinized in 2018 after certain comments on the randomization procedures led to the study being retracted and republished by the same research group [26,68]. In the assessment of the quality of the RCT, inappropriate allocation concealment was among the reasons noted [69]. The authors performed several complicated analyses to attempt to control for these deficiencies, which all seemed to confirm the original findings of that study. Thus, the updated publication documented similar findings, but the authors were unable to confirm adherence to randomization schemes, given that documentation was missing (supplemental appendix of [26]). Other high-quality dietary patterns such as the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet [70] and the prudent healthy pattern measured by the Healthy Eating Index [71] have also been associated with a reduced incidence of CVD events. However, the evidence collected and analyzed for these patterns is not as robust as the evidence provided by PREDIMED.

The aim of this study was to analyze the effects of the MedDiet as a diet and lifestyle, and not the effects of specific types of food. Studies focusing on the benefits of specific food groups in patients with cardiodiabesity were therefore excluded, even though some showed evidence of very strong preventive and therapeutic effects. Consumption of dairy fat, for instance, has been linked to a low incidence of MetS, while that of whole and skimmed cheese has been linked to a higher risk of MetS, and that of whole yogurt to a decrease in all the risk factors for MetS [72]. Indeed, while there have been concerns about a diet’s fat content since the last century, a number of reviews have shown that a low-fat diet is not effective at preventing cardiometabolic disease [73]. A direct association has also been observed between the consumption of tea and coffee and a lower incidence of MetS within the context of the MedDiet [74]. In another study of individuals with a moderate cardiovascular risk, moderate consumers of red wine had a lower risk of MetS than non-drinkers [75]. Interestingly, this effect was more pronounced in women. The consumption of sugary drinks has been linked to increased WC [76,77]. Mozaffarian et al. [78] conducted an in-depth review of the role of the main components of the MedDiet and other widely consumed foods in relation to health status. Their findings supported the widely agreed beneficial effects of fruit, nuts, fish, vegetables, vegetable oils, whole grains, beans, and yogurt, and the harmful effects of refined grains, starches, sugars, processed meats, high-sodium foods, and trans-fat foodstuffs. Foodstuffs for which there are still no proven beneficial or harmful effects include cheese, eggs, poultry, milk, butter, and unprocessed red meat. Albeit indirectly, the findings of this entry show the benefits of the main components of the MedDiet. As called for by previous studies, the relative effects of specific food groups need further investigation [6,55,58,65,66].

Our study has some limitations. Although some of the studies analyzed in the entry did not find a strong association between MedDiet adherence and the main outcomes analyzed, they did find positive links to intermediate risk factors. Certain discrepancies could be due to numerous aspects relating to the inherent limitations of the different studies.

In addition, when analyzing the literature, it is necessary to be aware of the different confounders and indices to ensure appropriate quantitative and/or qualitative measures [79]. The likelihood of heterogeneous measures of cause and effect should also be taken into account when interpreting the association between the MedDiet and the different health outcomes, as has been done in two recent meta-analyses that corroborate the results of the PICO analysis [80]. The level of heterogeneity of the included studies is also our concern.

This study is based on the 2014 study of the association between the MedDiet and cardiodiabesity by García-Fernández et al. [6]. The literature review was updated using the same search and a similar methodology to address a series of CQs based on scientific evidence on the association between the MedDiet and cardiodiabesity, with a view to informing future CPGs on how to treat and prevent obesity, MetS, T2DM, and CVD. The evidence uncovered provides solid support of an inverse relationship between MedDiet adherence and cardiodiabesity outcomes.

3. Conclusions

Recent scientific evidence has shown that the MedDiet, which is listed as a UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity [81,82] and referred to in the 2015–2020 American dietary guidelines [83] as an example of a healthy eating pattern, has a beneficial effect on health and sustainability. It also has an important social component [84,85]. The scientific basis for developing evidence-based CPGs consistent with international standards, such as those promoted by the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) and the United Kingdom’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), has been provided. The reviewed studies show strong evidence of an association between MedDiet adherence and outcomes in cardiodiabesity, which encompasses CVD, T2DM, MetS, and obesity. The MedDiet plays a role in obesity and MetS prevention in healthy or at-risk individuals, and in mortality risk reduction in overweight or obese individuals. Furthermore, it decreases the incidence of T2DM and CVD in healthy individuals, and reduces the severity of symptoms in individuals that already have those diseases. The scientific evidence seems to support the conclusion that MedDiet adherence is a preventive and therapeutic tool for cardiodiabesity.