The bone morphogenetic protein (Bmp) signaling pathway and the basic helix–loop–helix (bHLH) transcription factor Hand1 are known key regulators of cardiac development. In this study, we investigated the Bmp signaling regulation of Hand1 during cardiac outflow tract (OFT) development. In Bmp2 and Bmp4loss-of-function embryos with varying levels of Bmp in the heart, Hand1 is sensitively decreased in response to the dose of Bmp expression. In contrast, Hand1 in the heart is dramatically increased in Bmp4 gain-of-function embryos. We further identified and characterized the Bmp/Smad regulatory elements in Hand1. Combined transfection assays and chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) experiments indicated that Hand1 is directly activated and bound by Smads. In addition, we found that upon the treatment of Bmp2 and Bmp4, P19 cells induced Hand1 expression and favored cardiac differentiation. Together, our data indicated that the Bmp signaling pathway directly regulates Hand1 expression in a dose-dependent manner during heart development.

- Bmp signaling

- Hand1

- Smad

- transcriptional regulation

- heart development

- cardiomyocyte differentiation

1. Introduction

2. Results

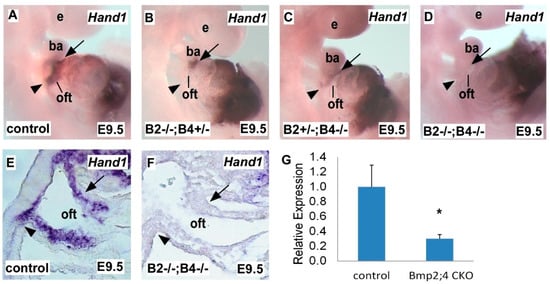

2.1. Hand1 Expression Decreases in a Dose-Sensitive Manner in Response to Bmp2 and Bmp4 Deficiency during Heart Development

2.2. Hand1 is Upregulated in Bmp4 OE Embryos

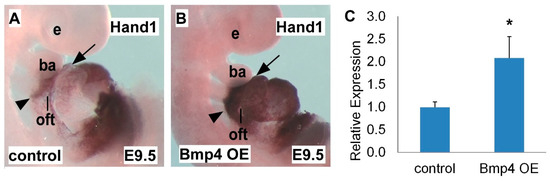

Finding that Hand1 expression is sensitive to Bmp loss-of-function, we next detected Hand1 expression in the heart with elevated Bmp signaling. Using a conditional Bmp4tetO gain-of-function allele (tetracycline inducible) crossed with the Mef2ccre driver [17[17][36],36], we specifically overexpressed Bmp4 in the SHF-derived heart structures (Bmp4 OE). We found that compared with the control heart (Figure 2A), the Bmp4 OE mutant heart had robustly expanded Hand1 expression in the SHF region and SHF-derived structures, including the OFT and RV (Figure 2B), indicated by in situ hybridization staining using a Hand1 probe. The qRT-PCR results further indicated that the elevated Bmp4 expression resulted in a significant increase in Hand1 in the Bmp4 OE mutant heart compared with the control heart at E9.5 (Figure 2C). These results indicated that Bmp signaling activates Hand1 expression during heart development, further supporting the conclusion that Hand1 expression sensitively responds to Bmp signaling dosage. Figure 2. Hand1 is upregulated upon Bmp4 overexpression (OE). (A,B) Whole-mount in situ hybridization of E9.5 Bmp4 OE embryo compared with control embryo; Bmp4 OE embryos expanded Hand1 expression in the SHF and SHF-derived OFT and RV. (C) qRT-PCR indicated increased Hand1 expression level in Bmp4 OE embryos compared with control embryos. e, eye; ba, branchial arch; oft, outflow tract; rv, right ventricle. Arrows and arrow heads point out in situ hybridization signals in the OFT and SHF. Data are presented as means ± s.e.m. * indicates p-value < 0.05.

Figure 2. Hand1 is upregulated upon Bmp4 overexpression (OE). (A,B) Whole-mount in situ hybridization of E9.5 Bmp4 OE embryo compared with control embryo; Bmp4 OE embryos expanded Hand1 expression in the SHF and SHF-derived OFT and RV. (C) qRT-PCR indicated increased Hand1 expression level in Bmp4 OE embryos compared with control embryos. e, eye; ba, branchial arch; oft, outflow tract; rv, right ventricle. Arrows and arrow heads point out in situ hybridization signals in the OFT and SHF. Data are presented as means ± s.e.m. * indicates p-value < 0.05.

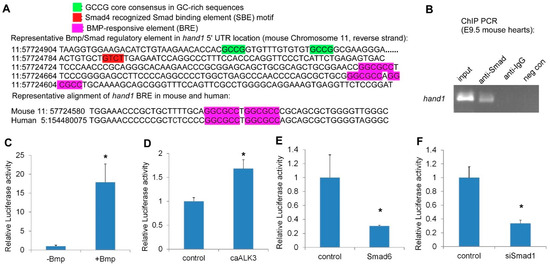

2.3. Hand1 Is a Direct Target Activated by the Canonical Bmp/Smad Signaling

Smad TFs function as the major signal transducers for receptors of the Bmp signaling pathway and can interact with specific DNA motifs to regulate gene expression [37,38,39,40][37][38][39][40]. The R-Smads and Smad4 are composed of two evolutionally conserved domains named Mad Homology 1 and 2 (MH1 and MH2). The MH1 domain is responsible for the Smad binding element’s (SBE) DNA-binding activity, while the MH2 domain is important for heterooligomeric Smad complexes formation and transcriptional activation [41,42][41][42]. In addition, based on chromatin immunoprecipitation and structural analysis, Smads have been shown to favor recognizing GC-rich elements (also termed BMP response element (BRE) in certain BMP-responsive genes) [43,44][43][44] and CAGAC motifs (also termed Smad binding element (SBE)) [45,46][45][46]. To determine if the Bmp/Smad signaling directly regulates Hand1, we undertook sequencing analysis and found that several phylogenetically conserved Smad recognition elements, including the GC-rich elements BRE and SBE, were located in the 5′UTR of Hand1 (Figure 3A and Figure S2). Figure 3. Hand1 is a direct target activated by the canonical Bmp/Smad signaling. (A) Representative Bmp/Smad regulatory element in Hand1 5′ UTR location (at upper) and sequence alignment (at lower), showing the conservation among mouse and human (source: Ensembl). (B) In Vivo ChIP PCR using E9.5 hearts with indicated antibodies to IP chromatin fragment. PCR band (size: 215bp) contains the Hand1 5′UTR Bmp/Smad regulatory element. (C–F) Hand1 5′UTR reporter luciferase assays: treated with Bmp (C), co-transfected with constitutively active ALK3 (caALK3) (D), pcDNA3.1-Smad6 (E), and pSR siSmad1 (F). Data are presented as means ± s.e.m. * indicates p-value < 0.05.

To determine whether Smads directly bind to Hand1, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) using a Smad1/5/8 antibody in E9.5 wild-type embryonic heart extracts. There was an obvious enrichment in the anti-Smad1/5/8 immunoprecipitated chromatin compared to the controls, indicating that Smad1/5/8 directly bound to the Hand1 chromatin (Figure 3B). To evaluate whether the potential Bmp/Smad regulatory elements in Hand1 are functional, we made a Hand1 5′UTR (Hand1 reporter) luciferase (Luc) reporter and performed luciferase assays in P19 cells. We found that Bmp treatment resulted in a dramatic and significant induction of Hand1 reporter activity (Figure 3C). Overexpression of the constitutively active Bmpr1a (caALK3) [47] also significantly increased Hand1 reporter activity (Figure 3D). In contrast, overexpression of Smad6, an inhibitory Smad, specifically competed with Smad4 for binding to Smad1 [48], and significantly repressed Hand1 reporter activity (Figure 3E). Hand1 Luc reporter activity was also dramatically decreased when using a knockdown Smad1 short hairpin RNA (shRNA) (Figure 3F). Together, these findings supported the idea that Hand1 is a direct target activated by the canonical Bmp/Smad signaling.

Figure 3. Hand1 is a direct target activated by the canonical Bmp/Smad signaling. (A) Representative Bmp/Smad regulatory element in Hand1 5′ UTR location (at upper) and sequence alignment (at lower), showing the conservation among mouse and human (source: Ensembl). (B) In Vivo ChIP PCR using E9.5 hearts with indicated antibodies to IP chromatin fragment. PCR band (size: 215bp) contains the Hand1 5′UTR Bmp/Smad regulatory element. (C–F) Hand1 5′UTR reporter luciferase assays: treated with Bmp (C), co-transfected with constitutively active ALK3 (caALK3) (D), pcDNA3.1-Smad6 (E), and pSR siSmad1 (F). Data are presented as means ± s.e.m. * indicates p-value < 0.05.

To determine whether Smads directly bind to Hand1, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) using a Smad1/5/8 antibody in E9.5 wild-type embryonic heart extracts. There was an obvious enrichment in the anti-Smad1/5/8 immunoprecipitated chromatin compared to the controls, indicating that Smad1/5/8 directly bound to the Hand1 chromatin (Figure 3B). To evaluate whether the potential Bmp/Smad regulatory elements in Hand1 are functional, we made a Hand1 5′UTR (Hand1 reporter) luciferase (Luc) reporter and performed luciferase assays in P19 cells. We found that Bmp treatment resulted in a dramatic and significant induction of Hand1 reporter activity (Figure 3C). Overexpression of the constitutively active Bmpr1a (caALK3) [47] also significantly increased Hand1 reporter activity (Figure 3D). In contrast, overexpression of Smad6, an inhibitory Smad, specifically competed with Smad4 for binding to Smad1 [48], and significantly repressed Hand1 reporter activity (Figure 3E). Hand1 Luc reporter activity was also dramatically decreased when using a knockdown Smad1 short hairpin RNA (shRNA) (Figure 3F). Together, these findings supported the idea that Hand1 is a direct target activated by the canonical Bmp/Smad signaling.

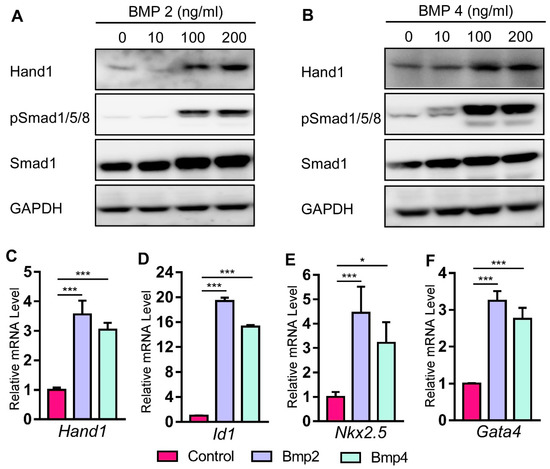

2.4. Bmp Induces Hand1 Expression during Cardiomyogenesis in P19 Cells

Both in vivo and in vitro studies have established the essential roles of Bmp signals in promoting cardiomyocyte differentiation [49,50,51][49][50][51]. P19 cells are undifferentiated stem cells derived from murine teratocarcinoma [52], which can differentiate into multiple cell types [53,54,55][53][54][55]. Previous studies have indicated that P19 cells can undergo cardiomyogenesis after treatment with chemical inducers such as DMSO, cardiac TFs such as Mef2c, and various cytokines [56,57,58,59,60][56][57][58][59][60]. It has been shown that Bmp treatment can promote cardiomyocyte differentiation in P19 cells by regulating Nkx2.5 activity [60]. To study Hand1 expression induced by Bmp2 and Bmp4 during cardiomyogenesis, we treated P19 cells with different concentrations of Bmp2 and Bmp4 for 6 days. Our western blot data indicated that both Bmp2 and Bmp4 induced Hand1 protein expression in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 4A,B). The qRT-PCR analysis also indicated that Hand1 expression was elevated in P19 cells after 6 days of Bmp2 and Bmp4 treatment (Figure 4C). Transcription factor Id1 is a known direct target of the canonical Bmp/Smad signaling pathway [61,62,63][61][62][63]. Bmp2/4 stimulation also induced Id1 gene expression, demonstrating that Bmp2 and Bmp4 activate the canonical Bmp/Smad signaling pathway (Figure 4D). Furthermore, we detected an elevated expression of cardiac TFs Nkx2.5 and Gata4 with Bmp treatment, indicating undergoing cardiomyogenesis in P19 cells (Figure 4E,F). Taken together, these data showed that the canonical Bmp/Smad signaling pathway induced Hand1 expression during cardiomyogenesis in P19 cells. Figure 4. Bmp2 and Bmp4 induce Hand1 expression in P19 cells. (A,B) P19 cells were stimulated with Bmp2 and 4 for 6 days. Levels of Hand1 were analyzed by western blotting. (C–F) Total RNA was harvested on day 6 with Bmp treatment for 6 days (100 ng/mL). qRT-PCR was performed for the analysis of Hand1, Id1, Nkx2.5, and Gata4 mRNA. Data are presented as means ± s.e.m. * indicates p-value < 0.05, *** indicates p-value < 0.001.

Figure 4. Bmp2 and Bmp4 induce Hand1 expression in P19 cells. (A,B) P19 cells were stimulated with Bmp2 and 4 for 6 days. Levels of Hand1 were analyzed by western blotting. (C–F) Total RNA was harvested on day 6 with Bmp treatment for 6 days (100 ng/mL). qRT-PCR was performed for the analysis of Hand1, Id1, Nkx2.5, and Gata4 mRNA. Data are presented as means ± s.e.m. * indicates p-value < 0.05, *** indicates p-value < 0.001.

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Mouse Alleles and Transgenic Lines

4.2. Antibodies and Reagents

4.3. Whole-Mount In Situ Hybridization

4.4. Quantitative Real Time RT-PCR

4.5. Chromatin Immunoprecipitation

4.6. Luciferase Reporter Assays

4.7. Western Blotting

4.8. Cell Culture

Supplementary Materials

References

- Warnes, C.A.; Liberthson, R.; Danielson, G.K.; Dore, A.; Harris, L.; Hoffman, J.I.; Somerville, J.; Williams, R.G.; Webb, G.D. Task force 1: The changing profile of congenital heart disease in adult life. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2001, 37, 1170–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- High, F.A.; Jain, R.; Stoller, J.Z.; Antonucci, N.B.; Lu, M.M.; Loomes, K.M.; Kaestner, K.H.; Pear, W.S.; Epstein, J.A. Murine Jagged1/Notch signaling in the second heart field orchestrates Fgf8 expression and tissue-tissue interactions during outflow tract development. J. Clin. Investig. 2009, 119, 1986–1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erhardt, S.; Zheng, M.J.; Zhao, X.L.; Le, T.P.; Findley, T.O.; Wang, J. The Cardiac Neural Crest Cells in Heart Development and Congenital Heart Defects. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2021, 8, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urist, M.R. Bone: Formation by autoinduction. Science 1965, 150, 893–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, X.H.; Derynck, R. Specificity and versatility in tgf-beta signaling through Smads. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2005, 21, 659–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ten Dijke, P.; Hill, C.S. New insights into TGF-beta-Smad signalling. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2004, 29, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derynck, R.; Zhang, Y.E. Smad-dependent and Smad-independent pathways in TGF-beta family signalling. Nature 2003, 425, 577–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, Y.; Wang, J.; Morikawa, Y.; Bonilla-Claudio, M.; Klysik, E.; Martin, J.F. Bmp signaling represses Vegfa to promote outflow tract cushion development. Development 2013, 140, 3395–3402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Greene, S.B.; Martin, J.F. BMP signaling in congenital heart disease: New developments and future directions. Birth Defects Res. Part A Clin. Mol. Teratol. 2011, 91, 441–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Selever, J.; Wang, D.; Lu, M.F.; Moses, K.A.; Schwartz, R.J.; Martin, J.F. Bmp4 signaling is required for outflow-tract septation and branchial-arch artery remodeling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 4489–4494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prall, O.W.; Menon, M.K.; Solloway, M.J.; Watanabe, Y.; Zaffran, S.; Bajolle, F.; Biben, C.; McBride, J.J.; Robertson, B.R.; Chaulet, H.; et al. An Nkx2-5/Bmp2/Smad1 negative feedback loop controls heart progenitor specification and proliferation. Cell 2007, 128, 947–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, L.; Lu, M.F.; Schwartz, R.J.; Martin, J.F. Bmp2 is essential for cardiac cushion epithelial-mesenchymal transition and myocardial patterning. Development 2005, 132, 5601–5611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Bradley, A. Mice deficient for BMP2 are nonviable and have defects in amnion/chorion and cardiac development. Development 1996, 122, 2977–2986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivera-Feliciano, J.; Tabin, C.J. Bmp2 instructs cardiac progenitors to form the heart-valve-inducing field. Dev. Biol. 2006, 295, 580–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, K.; Kulessa, H.; Tompkins, K.; Zhou, Y.; Batts, L.; Baldwin, H.S.; Hogan, B.L. An essential role of Bmp4 in the atrioventricular septation of the mouse heart. Genes Dev. 2003, 17, 2362–2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Shi, S.; Acosta, L.; Li, W.; Lu, J.; Bao, S.; Chen, Z.; Yang, Z.; Schneider, M.D.; Chien, K.R.; et al. BMP10 is essential for maintaining cardiac growth during murine cardiogenesis. Development 2004, 131, 2219–2231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Greene, S.B.; Bonilla-Claudio, M.; Tao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Bai, Y.; Huang, Z.; Black, B.L.; Wang, F.; Martin, J.F. Bmp signaling regulates myocardial differentiation from cardiac progenitors through a MicroRNA-mediated mechanism. Dev. Cell 2010, 19, 903–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollenberg, S.M.; Sternglanz, R.; Cheng, P.F.; Weintraub, H. Identification of a new family of tissue-specific basic helix-loop-helix proteins with a two-hybrid system. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1995, 15, 3813–3822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, I.C.; Anson-Cartwright, L.; Riley, P.; Reda, D.; Cross, J.C. The HAND1 basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor regulates trophoblast differentiation via multiple mechanisms. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2000, 20, 530–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firulli, A.B.; McFadden, D.G.; Lin, Q.; Srivastava, D.; Olson, E.N. Heart and extra-embryonic mesodermal defects in mouse embryos lacking the bHLH transcription factor Hand1. Nat. Genet. 1998, 18, 266–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, D.; Cserjesi, P.; Olson, E.N. A subclass of bHLH proteins required for cardiac morphogenesis. Science 1995, 270, 1995–1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, D.; Thomas, T.; Lin, Q.; Kirby, M.L.; Brown, D.; Olson, E.N. Regulation of cardiac mesodermal and neural crest development by the bHLH transcription factor, dHAND. Nat. Genet. 1997, 16, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cserjesi, P.; Brown, D.; Lyons, G.E.; Olson, E.N. Expression of the novel basic helix-loop-helix gene eHAND in neural crest derivatives and extraembryonic membranes during mouse development. Dev. Biol. 1995, 170, 664–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vincentz, J.W.; Toolan, K.P.; Zhang, W.; Firulli, A.B. Hand factor ablation causes defective left ventricular chamber development and compromised adult cardiac function. PLoS Genet. 2017, 13, e1006922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smart, N.; Dube, K.N.; Riley, P.R. Identification of Thymosin beta4 as an effector of Hand1-mediated vascular development. Nat. Commun. 2010, 1, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Firulli, A.B. A HANDful of questions: The molecular biology of the heart and neural crest derivatives (HAND)-subclass of basic helix-loop-helix transcription factors. Gene 2003, 312, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, P.; Anson-Cartwright, L.; Cross, J.C. The Hand1 bHLH transcription factor is essential for placentation and cardiac morphogenesis. Nat. Genet. 1998, 18, 271–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risebro, C.A.; Smart, N.; Dupays, L.; Breckenridge, R.; Mohun, T.J.; Riley, P.R. Hand1 regulates cardiomyocyte proliferation versus differentiation in the developing heart. Development 2006, 133, 4595–4606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firulli, B.A.; George, R.M.; Harkin, J.; Toolan, K.P.; Gao, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Field, L.J.; Liu, Y.; Shou, W.; et al. HAND1 loss-of-function within the embryonic myocardium reveals survivable congenital cardiac defects and adult heart failure. Cardiovasc. Res. 2020, 116, 605–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reamon-Buettner, S.M.; Ciribilli, Y.; Traverso, I.; Kuhls, B.; Inga, A.; Borlak, J. A functional genetic study identifies HAND1 mutations in septation defects of the human heart. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2009, 18, 3567–3578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.M.; Dai, X.Y.; Qiu, X.B.; Yuan, F.; Li, R.G.; Xu, Y.J.; Qu, X.K.; Huang, R.T.; Xue, S.; Yang, Y.Q. HAND1 loss-of-function mutation associated with familial dilated cardiomyopathy. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2016, 54, 1161–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamagishi, H.; Olson, E.N.; Srivastava, D. The basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor, dHAND, is required for vascular development. J. Clin. Investig. 2000, 105, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.M.; Wang, J.; Qiu, X.B.; Yuan, F.; Li, R.G.; Xu, Y.J.; Qu, X.K.; Shi, H.Y.; Hou, X.M.; Huang, R.T.; et al. A HAND2 Loss-of-Function Mutation Causes Familial Ventricular Septal Defect and Pulmonary Stenosis. G3 2016, 6, 987–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buckingham, M.; Meilhac, S.; Zaffran, S. Building the mammalian heart from two sources of myocardial cells. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2005, 6, 826–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brade, T.; Pane, L.S.; Moretti, A.; Chien, K.R.; Laugwitz, K.L. Embryonic heart progenitors and cardiogenesis. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2013, 3, a013847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonilla-Claudio, M.; Wang, J.; Bai, Y.; Klysik, E.; Selever, J.; Martin, J.F. Bmp signaling regulates a dose-dependent transcriptional program to control facial skeletal development. Development 2012, 139, 709–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macias, M.J.; Martin-Malpartida, P.; Massague, J. Structural determinants of Smad function in TGF-beta signaling. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2015, 40, 296–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Malpartida, P.; Batet, M.; Kaczmarska, Z.; Freier, R.; Gomes, T.; Aragon, E.; Zou, Y.; Wang, Q.; Xi, Q.; Ruiz, L.; et al. Structural basis for genome wide recognition of 5-bp GC motifs by SMAD transcription factors. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derynck, R.; Zhang, Y.; Feng, X.H. Smads: Transcriptional activators of TGF-beta responses. Cell 1998, 95, 737–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massague, J.; Seoane, J.; Wotton, D. Smad transcription factors. Genes Dev. 2005, 19, 2783–2810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morikawa, M.; Koinuma, D.; Miyazono, K.; Heldin, C.H. Genome-wide mechanisms of Smad binding. Oncogene 2013, 32, 1609–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Massague, J. Mechanisms of TGF-beta signaling from cell membrane to the nucleus. Cell 2003, 113, 685–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morikawa, M.; Koinuma, D.; Tsutsumi, S.; Vasilaki, E.; Kanki, Y.; Heldin, C.H.; Aburatani, H.; Miyazono, K. ChIP-seq reveals cell type-specific binding patterns of BMP-specific Smads and a novel binding motif. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, 8712–8727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Johnson, K.; Chen, H.J.; Carroll, S.; Laughon, A. Drosophila Mad binds to DNA and directly mediates activation of vestigial by Decapentaplegic. Nature 1997, 388, 304–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BabuRajendran, N.; Palasingam, P.; Narasimhan, K.; Sun, W.; Prabhakar, S.; Jauch, R.; Kolatkar, P.R. Structure of Smad1 MH1/DNA complex reveals distinctive rearrangements of BMP and TGF-beta effectors. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38, 3477–3488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chai, N.; Li, W.X.; Wang, J.; Wang, Z.X.; Yang, S.M.; Wu, J.W. Structural basis for the Smad5 MH1 domain to recognize different DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, 6255–6257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujii, M.; Takeda, K.; Imamura, T.; Aoki, H.; Sampath, T.K.; Enomoto, S.; Kawabata, M.; Kato, M.; Ichijo, H.; Miyazono, K. Roles of bone morphogenetic protein type I receptors and Smad proteins in osteoblast and chondroblast differentiation. Mol. Biol. Cell 1999, 10, 3801–3813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hata, A.; Lagna, G.; Massague, J.; Hemmati-Brivanlou, A. Smad6 inhibits BMP/Smad1 signaling by specifically competing with the Smad4 tumor suppressor. Genes Dev. 1998, 12, 186–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callis, T.E.; Cao, D.; Wang, D.Z. Bone morphogenetic protein signaling modulates myocardin transactivation of cardiac genes. Circ. Res. 2005, 97, 992–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.O., 3rd; Chi, X.; Garcia-Gras, E.; Shirai, M.; Feng, X.H.; Schwartz, R.J. The cardiac determination factor, Nkx2-5, is activated by mutual cofactors GATA-4 and Smad1/4 via a novel upstream enhancer. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 10659–10669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Katsev, S.; Cai, C.; Evans, S. BMP signaling is required for heart formation in vertebrates. Dev. Biol. 2000, 224, 226–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBurney, M.W.; Jones-Villeneuve, E.M.; Edwards, M.K.; Anderson, P.J. Control of muscle and neuronal differentiation in a cultured embryonal carcinoma cell line. Nature 1982, 299, 165–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McBurney, M.W. P19 embryonal carcinoma cells. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 1993, 37, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wilton, S.; Skerjanc, I. Factors in serum regulate muscle development in P19 cells. In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol. Anim. 1999, 35, 175–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skerjanc, I.S. Cardiac and skeletal muscle development in P19 embryonal carcinoma cells. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 1999, 9, 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grepin, C.; Robitaille, L.; Antakly, T.; Nemer, M. Inhibition of transcription factor GATA-4 expression blocks in vitro cardiac muscle differentiation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1995, 15, 4095–4102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, M.; Rogerson, P.J.; Wilton, S.; Skerjanc, I.S. Nkx2-5 activity is essential for cardiomyogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 42252–42258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skerjanc, I.S.; Petropoulos, H.; Ridgeway, A.G.; Wilton, S. Myocyte enhancer factor 2C and Nkx2-5 up-regulate each other's expression and initiate cardiomyogenesis in P19 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 34904–34910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monzen, K.; Shiojima, I.; Hiroi, Y.; Kudoh, S.; Oka, T.; Takimoto, E.; Hayashi, D.; Hosoda, T.; Habara-Ohkubo, A.; Nakaoka, T.; et al. Bone morphogenetic proteins induce cardiomyocyte differentiation through the mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase TAK1 and cardiac transcription factors Csx/Nkx-2.5 and GATA-4. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999, 19, 7096–7105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, M.; Karamboulas, C.; Rogerson, P.J.; Skerjanc, I.S. BMP signaling regulates Nkx2-5 activity during cardiomyogenesis. FEBS Lett. 2001, 509, 126–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benezra, R.; Davis, R.L.; Lockshon, D.; Turner, D.L.; Weintraub, H. The protein Id: A negative regulator of helix-loop-helix DNA binding proteins. Cell 1990, 61, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, J.D.; Deed, R.W.; Craggs, G.; Sablitzky, F. Id helix-loop-helix proteins in cell growth and differentiation. Trends Cell Biol. 1998, 8, 58–65. [Google Scholar]

- Hollnagel, A.; Oehlmann, V.; Heymer, J.; Ruther, U.; Nordheim, A. Id genes are direct targets of bone morphogenetic protein induction in embryonic stem cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 19838–19845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firulli, B.A.; McConville, D.P.; Byers, J.S., 3rd; Vincentz, J.W.; Barnes, R.M.; Firulli, A.B. Analysis of a Hand1 hypomorphic allele reveals a critical threshold for embryonic viability. Dev. Dyn. 2010, 239, 2748–2760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, T.; Yamagishi, H.; Overbeek, P.A.; Olson, E.N.; Srivastava, D. The bHLH factors, dHAND and eHAND, specify pulmonary and systemic cardiac ventricles independent of left-right sidedness. Dev. Biol. 1998, 196, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaussin, V.; Van de Putte, T.; Mishina, Y.; Hanks, M.C.; Zwijsen, A.; Huylebroeck, D.; Behringer, R.R.; Schneider, M.D. Endocardial cushion and myocardial defects after cardiac myocyte-specific conditional deletion of the bone morphogenetic protein receptor ALK3. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 2878–2883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincentz, J.W.; Casasnovas, J.J.; Barnes, R.M.; Que, J.; Clouthier, D.E.; Wang, J.; Firulli, A.B. Exclusion of Dlx5/6 expression from the distal-most mandibular arches enables BMP-mediated specification of the distal cap. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 7563–7568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winnier, G.; Blessing, M.; Labosky, P.A.; Hogan, B.L. Bone morphogenetic protein-4 is required for mesoderm formation and patterning in the mouse. Genes Dev. 1995, 9, 2105–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schultheiss, T.M.; Burch, J.B.; Lassar, A.B. A role for bone morphogenetic proteins in the induction of cardiac myogenesis. Genes Dev. 1997, 11, 451–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuasa, S.; Itabashi, Y.; Koshimizu, U.; Tanaka, T.; Sugimura, K.; Kinoshita, M.; Hattori, F.; Fukami, S.; Shimazaki, T.; Ogawa, S.; et al. Transient inhibition of BMP signaling by Noggin induces cardiomyocyte differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 2005, 23, 607–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McFadden, D.G.; Barbosa, A.C.; Richardson, J.A.; Schneider, M.D.; Srivastava, D.; Olson, E.N. The Hand1 and Hand2 transcription factors regulate expansion of the embryonic cardiac ventricles in a gene dosage-dependent manner. Development 2005, 132, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Klysik, E.; Sood, S.; Johnson, R.L.; Wehrens, X.H.; Martin, J.F. Pitx2 prevents susceptibility to atrial arrhythmias by inhibiting left-sided pacemaker specification. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 9753–9758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

References

- Warnes, C.A.; Liberthson, R.; Danielson, G.K.; Dore, A.; Harris, L.; Hoffman, J.I.; Somerville, J.; Williams, R.G.; Webb, G.D. Task force 1: The changing profile of congenital heart disease in adult life. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2001, 37, 1170–1175.

- High, F.A.; Jain, R.; Stoller, J.Z.; Antonucci, N.B.; Lu, M.M.; Loomes, K.M.; Kaestner, K.H.; Pear, W.S.; Epstein, J.A. Murine Jagged1/Notch signaling in the second heart field orchestrates Fgf8 expression and tissue-tissue interactions during outflow tract development. J. Clin. Investig. 2009, 119, 1986–1996.

- Erhardt, S.; Zheng, M.J.; Zhao, X.L.; Le, T.P.; Findley, T.O.; Wang, J. The Cardiac Neural Crest Cells in Heart Development and Congenital Heart Defects. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2021, 8, 89.

- Urist, M.R. Bone: Formation by autoinduction. Science 1965, 150, 893–899.

- Feng, X.H.; Derynck, R. Specificity and versatility in tgf-beta signaling through Smads. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2005, 21, 659–693.

- ten Dijke, P.; Hill, C.S. New insights into TGF-beta-Smad signalling. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2004, 29, 265–273.

- Derynck, R.; Zhang, Y.E. Smad-dependent and Smad-independent pathways in TGF-beta family signalling. Nature 2003, 425, 577–584.

- Bai, Y.; Wang, J.; Morikawa, Y.; Bonilla-Claudio, M.; Klysik, E.; Martin, J.F. Bmp signaling represses Vegfa to promote outflow tract cushion development. Development 2013, 140, 3395–3402.

- Wang, J.; Greene, S.B.; Martin, J.F. BMP signaling in congenital heart disease: New developments and future directions. Birth Defects Res. Part A Clin. Mol. Teratol. 2011, 91, 441–448.

- Liu, W.; Selever, J.; Wang, D.; Lu, M.F.; Moses, K.A.; Schwartz, R.J.; Martin, J.F. Bmp4 signaling is required for outflow-tract septation and branchial-arch artery remodeling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 4489–4494.

- Prall, O.W.; Menon, M.K.; Solloway, M.J.; Watanabe, Y.; Zaffran, S.; Bajolle, F.; Biben, C.; McBride, J.J.; Robertson, B.R.; Chaulet, H.; et al. An Nkx2-5/Bmp2/Smad1 negative feedback loop controls heart progenitor specification and proliferation. Cell 2007, 128, 947–959.

- Ma, L.; Lu, M.F.; Schwartz, R.J.; Martin, J.F. Bmp2 is essential for cardiac cushion epithelial-mesenchymal transition and myocardial patterning. Development 2005, 132, 5601–5611.

- Zhang, H.; Bradley, A. Mice deficient for BMP2 are nonviable and have defects in amnion/chorion and cardiac development. Development 1996, 122, 2977–2986.

- Rivera-Feliciano, J.; Tabin, C.J. Bmp2 instructs cardiac progenitors to form the heart-valve-inducing field. Dev. Biol. 2006, 295, 580–588.

- Jiao, K.; Kulessa, H.; Tompkins, K.; Zhou, Y.; Batts, L.; Baldwin, H.S.; Hogan, B.L. An essential role of Bmp4 in the atrioventricular septation of the mouse heart. Genes Dev. 2003, 17, 2362–2367.

- Chen, H.; Shi, S.; Acosta, L.; Li, W.; Lu, J.; Bao, S.; Chen, Z.; Yang, Z.; Schneider, M.D.; Chien, K.R.; et al. BMP10 is essential for maintaining cardiac growth during murine cardiogenesis. Development 2004, 131, 2219–2231.

- Wang, J.; Greene, S.B.; Bonilla-Claudio, M.; Tao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Bai, Y.; Huang, Z.; Black, B.L.; Wang, F.; Martin, J.F. Bmp signaling regulates myocardial differentiation from cardiac progenitors through a MicroRNA-mediated mechanism. Dev. Cell 2010, 19, 903–912.

- Hollenberg, S.M.; Sternglanz, R.; Cheng, P.F.; Weintraub, H. Identification of a new family of tissue-specific basic helix-loop-helix proteins with a two-hybrid system. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1995, 15, 3813–3822.

- Scott, I.C.; Anson-Cartwright, L.; Riley, P.; Reda, D.; Cross, J.C. The HAND1 basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor regulates trophoblast differentiation via multiple mechanisms. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2000, 20, 530–541.

- Firulli, A.B.; McFadden, D.G.; Lin, Q.; Srivastava, D.; Olson, E.N. Heart and extra-embryonic mesodermal defects in mouse embryos lacking the bHLH transcription factor Hand1. Nat. Genet. 1998, 18, 266–270.

- Srivastava, D.; Cserjesi, P.; Olson, E.N. A subclass of bHLH proteins required for cardiac morphogenesis. Science 1995, 270, 1995–1999.

- Srivastava, D.; Thomas, T.; Lin, Q.; Kirby, M.L.; Brown, D.; Olson, E.N. Regulation of cardiac mesodermal and neural crest development by the bHLH transcription factor, dHAND. Nat. Genet. 1997, 16, 154–160.

- Cserjesi, P.; Brown, D.; Lyons, G.E.; Olson, E.N. Expression of the novel basic helix-loop-helix gene eHAND in neural crest derivatives and extraembryonic membranes during mouse development. Dev. Biol. 1995, 170, 664–678.

- Vincentz, J.W.; Toolan, K.P.; Zhang, W.; Firulli, A.B. Hand factor ablation causes defective left ventricular chamber development and compromised adult cardiac function. PLoS Genet. 2017, 13, e1006922.

- Smart, N.; Dube, K.N.; Riley, P.R. Identification of Thymosin beta4 as an effector of Hand1-mediated vascular development. Nat. Commun. 2010, 1, 46.

- Firulli, A.B. A HANDful of questions: The molecular biology of the heart and neural crest derivatives (HAND)-subclass of basic helix-loop-helix transcription factors. Gene 2003, 312, 27–40.

- Riley, P.; Anson-Cartwright, L.; Cross, J.C. The Hand1 bHLH transcription factor is essential for placentation and cardiac morphogenesis. Nat. Genet. 1998, 18, 271–275.

- Risebro, C.A.; Smart, N.; Dupays, L.; Breckenridge, R.; Mohun, T.J.; Riley, P.R. Hand1 regulates cardiomyocyte proliferation versus differentiation in the developing heart. Development 2006, 133, 4595–4606.

- Firulli, B.A.; George, R.M.; Harkin, J.; Toolan, K.P.; Gao, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Field, L.J.; Liu, Y.; Shou, W.; et al. HAND1 loss-of-function within the embryonic myocardium reveals survivable congenital cardiac defects and adult heart failure. Cardiovasc. Res. 2020, 116, 605–618.

- Reamon-Buettner, S.M.; Ciribilli, Y.; Traverso, I.; Kuhls, B.; Inga, A.; Borlak, J. A functional genetic study identifies HAND1 mutations in septation defects of the human heart. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2009, 18, 3567–3578.

- Zhou, Y.M.; Dai, X.Y.; Qiu, X.B.; Yuan, F.; Li, R.G.; Xu, Y.J.; Qu, X.K.; Huang, R.T.; Xue, S.; Yang, Y.Q. HAND1 loss-of-function mutation associated with familial dilated cardiomyopathy. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2016, 54, 1161–1167.

- Yamagishi, H.; Olson, E.N.; Srivastava, D. The basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor, dHAND, is required for vascular development. J. Clin. Investig. 2000, 105, 261–270.

- Sun, Y.M.; Wang, J.; Qiu, X.B.; Yuan, F.; Li, R.G.; Xu, Y.J.; Qu, X.K.; Shi, H.Y.; Hou, X.M.; Huang, R.T.; et al. A HAND2 Loss-of-Function Mutation Causes Familial Ventricular Septal Defect and Pulmonary Stenosis. G3 2016, 6, 987–992.

- Buckingham, M.; Meilhac, S.; Zaffran, S. Building the mammalian heart from two sources of myocardial cells. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2005, 6, 826–835.

- Brade, T.; Pane, L.S.; Moretti, A.; Chien, K.R.; Laugwitz, K.L. Embryonic heart progenitors and cardiogenesis. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2013, 3, a013847.

- Bonilla-Claudio, M.; Wang, J.; Bai, Y.; Klysik, E.; Selever, J.; Martin, J.F. Bmp signaling regulates a dose-dependent transcriptional program to control facial skeletal development. Development 2012, 139, 709–719.

- Macias, M.J.; Martin-Malpartida, P.; Massague, J. Structural determinants of Smad function in TGF-beta signaling. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2015, 40, 296–308.

- Martin-Malpartida, P.; Batet, M.; Kaczmarska, Z.; Freier, R.; Gomes, T.; Aragon, E.; Zou, Y.; Wang, Q.; Xi, Q.; Ruiz, L.; et al. Structural basis for genome wide recognition of 5-bp GC motifs by SMAD transcription factors. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 2070.

- Derynck, R.; Zhang, Y.; Feng, X.H. Smads: Transcriptional activators of TGF-beta responses. Cell 1998, 95, 737–740.

- Massague, J.; Seoane, J.; Wotton, D. Smad transcription factors. Genes Dev. 2005, 19, 2783–2810.

- Morikawa, M.; Koinuma, D.; Miyazono, K.; Heldin, C.H. Genome-wide mechanisms of Smad binding. Oncogene 2013, 32, 1609–1615.

- Shi, Y.; Massague, J. Mechanisms of TGF-beta signaling from cell membrane to the nucleus. Cell 2003, 113, 685–700.

- Morikawa, M.; Koinuma, D.; Tsutsumi, S.; Vasilaki, E.; Kanki, Y.; Heldin, C.H.; Aburatani, H.; Miyazono, K. ChIP-seq reveals cell type-specific binding patterns of BMP-specific Smads and a novel binding motif. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, 8712–8727.

- Kim, J.; Johnson, K.; Chen, H.J.; Carroll, S.; Laughon, A. Drosophila Mad binds to DNA and directly mediates activation of vestigial by Decapentaplegic. Nature 1997, 388, 304–308.

- BabuRajendran, N.; Palasingam, P.; Narasimhan, K.; Sun, W.; Prabhakar, S.; Jauch, R.; Kolatkar, P.R. Structure of Smad1 MH1/DNA complex reveals distinctive rearrangements of BMP and TGF-beta effectors. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38, 3477–3488.

- Chai, N.; Li, W.X.; Wang, J.; Wang, Z.X.; Yang, S.M.; Wu, J.W. Structural basis for the Smad5 MH1 domain to recognize different DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, 6255–6257.

- Fujii, M.; Takeda, K.; Imamura, T.; Aoki, H.; Sampath, T.K.; Enomoto, S.; Kawabata, M.; Kato, M.; Ichijo, H.; Miyazono, K. Roles of bone morphogenetic protein type I receptors and Smad proteins in osteoblast and chondroblast differentiation. Mol. Biol. Cell 1999, 10, 3801–3813.

- Hata, A.; Lagna, G.; Massague, J.; Hemmati-Brivanlou, A. Smad6 inhibits BMP/Smad1 signaling by specifically competing with the Smad4 tumor suppressor. Genes Dev. 1998, 12, 186–197.

- Callis, T.E.; Cao, D.; Wang, D.Z. Bone morphogenetic protein signaling modulates myocardin transactivation of cardiac genes. Circ. Res. 2005, 97, 992–1000.

- Brown, C.O., 3rd; Chi, X.; Garcia-Gras, E.; Shirai, M.; Feng, X.H.; Schwartz, R.J. The cardiac determination factor, Nkx2-5, is activated by mutual cofactors GATA-4 and Smad1/4 via a novel upstream enhancer. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 10659–10669.

- Shi, Y.; Katsev, S.; Cai, C.; Evans, S. BMP signaling is required for heart formation in vertebrates. Dev. Biol. 2000, 224, 226–237.

- McBurney, M.W.; Jones-Villeneuve, E.M.; Edwards, M.K.; Anderson, P.J. Control of muscle and neuronal differentiation in a cultured embryonal carcinoma cell line. Nature 1982, 299, 165–167.

- McBurney, M.W. P19 embryonal carcinoma cells. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 1993, 37, 135–140.

- Wilton, S.; Skerjanc, I. Factors in serum regulate muscle development in P19 cells. In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol. Anim. 1999, 35, 175–177.

- Skerjanc, I.S. Cardiac and skeletal muscle development in P19 embryonal carcinoma cells. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 1999, 9, 139–143.

- Grepin, C.; Robitaille, L.; Antakly, T.; Nemer, M. Inhibition of transcription factor GATA-4 expression blocks in vitro cardiac muscle differentiation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1995, 15, 4095–4102.

- Jamali, M.; Rogerson, P.J.; Wilton, S.; Skerjanc, I.S. Nkx2-5 activity is essential for cardiomyogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 42252–42258.

- Skerjanc, I.S.; Petropoulos, H.; Ridgeway, A.G.; Wilton, S. Myocyte enhancer factor 2C and Nkx2-5 up-regulate each other's expression and initiate cardiomyogenesis in P19 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 34904–34910.

- Monzen, K.; Shiojima, I.; Hiroi, Y.; Kudoh, S.; Oka, T.; Takimoto, E.; Hayashi, D.; Hosoda, T.; Habara-Ohkubo, A.; Nakaoka, T.; et al. Bone morphogenetic proteins induce cardiomyocyte differentiation through the mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase TAK1 and cardiac transcription factors Csx/Nkx-2.5 and GATA-4. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999, 19, 7096–7105.

- Jamali, M.; Karamboulas, C.; Rogerson, P.J.; Skerjanc, I.S. BMP signaling regulates Nkx2-5 activity during cardiomyogenesis. FEBS Lett. 2001, 509, 126–130.

- Benezra, R.; Davis, R.L.; Lockshon, D.; Turner, D.L.; Weintraub, H. The protein Id: A negative regulator of helix-loop-helix DNA binding proteins. Cell 1990, 61, 49–59.

- Norton, J.D.; Deed, R.W.; Craggs, G.; Sablitzky, F. Id helix-loop-helix proteins in cell growth and differentiation. Trends Cell Biol. 1998, 8, 58–65.

- Hollnagel, A.; Oehlmann, V.; Heymer, J.; Ruther, U.; Nordheim, A. Id genes are direct targets of bone morphogenetic protein induction in embryonic stem cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 19838–19845.

- Firulli, B.A.; McConville, D.P.; Byers, J.S., 3rd; Vincentz, J.W.; Barnes, R.M.; Firulli, A.B. Analysis of a Hand1 hypomorphic allele reveals a critical threshold for embryonic viability. Dev. Dyn. 2010, 239, 2748–2760.

- Thomas, T.; Yamagishi, H.; Overbeek, P.A.; Olson, E.N.; Srivastava, D. The bHLH factors, dHAND and eHAND, specify pulmonary and systemic cardiac ventricles independent of left-right sidedness. Dev. Biol. 1998, 196, 228–236.

- Gaussin, V.; Van de Putte, T.; Mishina, Y.; Hanks, M.C.; Zwijsen, A.; Huylebroeck, D.; Behringer, R.R.; Schneider, M.D. Endocardial cushion and myocardial defects after cardiac myocyte-specific conditional deletion of the bone morphogenetic protein receptor ALK3. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 2878–2883.

- Vincentz, J.W.; Casasnovas, J.J.; Barnes, R.M.; Que, J.; Clouthier, D.E.; Wang, J.; Firulli, A.B. Exclusion of Dlx5/6 expression from the distal-most mandibular arches enables BMP-mediated specification of the distal cap. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 7563–7568.

- Winnier, G.; Blessing, M.; Labosky, P.A.; Hogan, B.L. Bone morphogenetic protein-4 is required for mesoderm formation and patterning in the mouse. Genes Dev. 1995, 9, 2105–2116.

- Schultheiss, T.M.; Burch, J.B.; Lassar, A.B. A role for bone morphogenetic proteins in the induction of cardiac myogenesis. Genes Dev. 1997, 11, 451–462.

- Yuasa, S.; Itabashi, Y.; Koshimizu, U.; Tanaka, T.; Sugimura, K.; Kinoshita, M.; Hattori, F.; Fukami, S.; Shimazaki, T.; Ogawa, S.; et al. Transient inhibition of BMP signaling by Noggin induces cardiomyocyte differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 2005, 23, 607–611.

- McFadden, D.G.; Barbosa, A.C.; Richardson, J.A.; Schneider, M.D.; Srivastava, D.; Olson, E.N. The Hand1 and Hand2 transcription factors regulate expansion of the embryonic cardiac ventricles in a gene dosage-dependent manner. Development 2005, 132, 189–201.

- Wang, J.; Klysik, E.; Sood, S.; Johnson, R.L.; Wehrens, X.H.; Martin, J.F. Pitx2 prevents susceptibility to atrial arrhythmias by inhibiting left-sided pacemaker specification. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 9753–9758.