Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Alberto Cordero and Version 2 by Bruce Ren.

Coronary artery disease is one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality, and its prevalence increases with age. The growing number of older patients and their differential characteristics make its management a challenge in clinical practice.

- elderly

- acute coronary syndrome

- myocardial infarction

Note: The entry will be online only after author check and submit it.

1. Introduction

Coronary artery disease is one of the leading causes of mortality and morbidity worldwide, and its prevalence increases with age [1][2][3][1,2,3]. The lengthening of life expectancy has caused the proportion of older patients admitted for acute coronary syndrome (ACS) to rise significantly, with one in every three patients presenting with ACS being over 75 years old [4].

The older patient has clinical peculiarities that pose a higher risk in this setting, such as comorbidities and geriatric syndromes. Diagnosis and therapeutic approach are also more challenging in this age group due to a higher prevalence of atypical features and an increased vulnerability to side effects and complications [5][6][5,6]. Moreover, older patients are often underrepresented in large clinical trials, and there is a paucity of specific evidence.

2. Diagnostic Approach in the Older Patient

The ACS diagnostic pathway is the same as recommended for the general population. However, some peculiarities and challenges should be noted. Atypical symptoms are more frequent, and, together with communication difficulties, may lead to delays or misdiagnoses [7]. Another source of diagnostic uncertainties is the higher frequency of baseline electrocardiogram changes, such as bundle branch block or pacemaker rhythm [7].

Even more challenging may be the interpretation of troponin elevations in the older patient. Elevated basal troponin levels have been described, and it is known that age > 60 years is associated to higher 99th percentile upper reference limit [8][9][10][8,9,10]. Boeddinghaus et al. analyzed the diagnostic performance of the 0/1 h algorithm recommended by the European Society of Cardiology in three age groups (<55 years, young; 55–70 years, middle age; ≥70 years, old) [11]. They found similar rule-out safety (sensitivity) while decreased rule-in accuracy (specificity), 93% for young, 80% for middle-age, and 55% for old (p < 0.001). Using slightly higher cut-off troponin concentrations specific for older patients resulted in increased specificity while maintaining a high sensitivity, especially when using troponin-I [11]. However, the main consensus documents and clinical practice guidelines do not currently support the use of age-specific thresholds [12][13][12,13]. Further research is warranted to clarify the best approach.

3. ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction (STEMI) Patients

Emergent reperfusion, especially primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), is the standard of care in STEMI, and its widespread use has improved both short and long-term prognosis [14][15][14,15]. This applies equally to the older patient, but some peculiarities must be noted.

Regarding diagnosis, atypical clinical presentation and communication difficulties (derived from confusional states or cognitive impairment) are more frequent in the elderly and may delay diagnosis [16][17][16,17]. Baseline electrocardiogram alterations may also make diagnosis difficult in older patients, since some findings, including history of previous myocardial infarction, pacemaker stimulation, or the presence of left bundle branch block, are common [14][16][14,16].

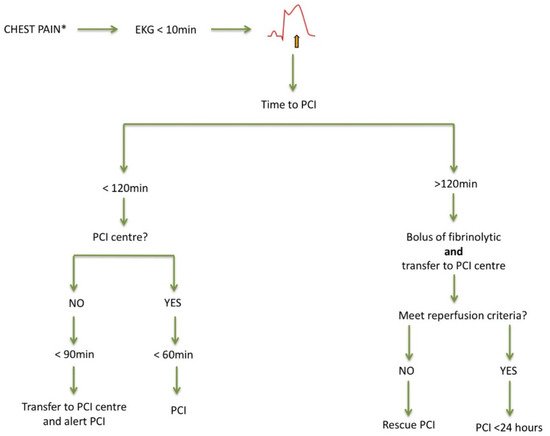

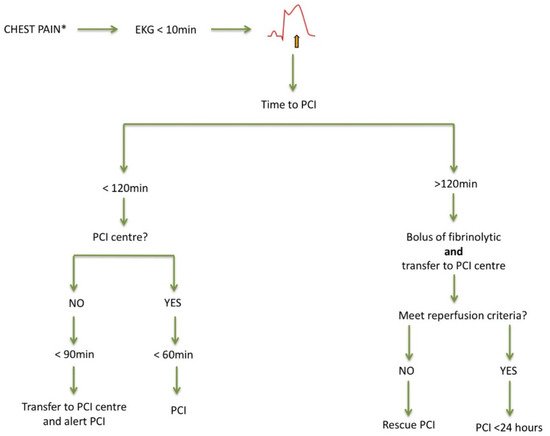

According to current guidelines, primary PCI performed <120 min since the first medical contact is the treatment of choice, irrespective of age. PCI is superior to fibrinolysis in reducing mortality, reinfarction, or stroke [18]. It is recommended to use radial access and stenting with new-generation drug-eluting stents, since this strategy is associated with fewer events [18][19][18,19]. Otherwise, and in the absence of contraindications, fibrinolytic therapy is recommended, always within the first 12 h since symptom onset, and providing the highest benefit when administered within the first two hours. Afterwards, the patient must be transferred to a center with a PCI-capable facility (Figure 1) [18]. Thus, if reperfusion is not achieved (ST-segment resolution < 50% within 60–90 min of fibrinolytic administration) or in the presence of persistent chest pain, worsening ischemia, or hemodynamic or electrical instability, rescue PCI is indicated. In other cases, routine early (2–24 h after fibrinolysis) PCI is indicated. Age should not be considered a contraindication to fibrinolysis, since several studies including elderly patients with STEMI receiving this therapy did not find significant differences in the number of major bleedings requiring transfusion compared to PCI or even no reperfusion [20]. On the other hand, the incidence of intracranial bleeding increases with age. Nevertheless, in the STREAM trial, the risk of intracranial hemorrhage was reduced after adjusting the fibrinolytic dose of tenecteplase to 50% in patients older than 75 years of age [21].

Figure 1. Management of acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Adapted from [16]. EKG: electrocardiogram; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention. * Atypical presentation is common.

Despite current evidence and recommendations, older patients are still less likely to receive reperfusion treatment when compared with their younger counterparts [3][16][19][22][3,16,19,22]. Efforts should be made to improve this picture, as invasive strategies in STEMI associate greater survival in elderly patients, and there is no upper age limit for urgent reperfusion [3][19][22][23][3,19,22,23].

Regarding prognostic medication in the elderly, current recommendations are not different from those made in younger patients. They improve prognosis [15], though titration may often be slower [14][18][14,18]. Moreover, elderly patients should participate in a complete rehabilitation program whenever possible, adapted to age conditions, and addressing comorbidities and geriatric syndromes, which in turn improves both prognosis and quality of life [18]. Unfortunately, these patients are, by far, the least enrolled in these programs [24].

4. Non-STEMI (NSTEMI) Patients: Invasive Versus Conservative Treatment?

Balancing the benefit/risk of harm is crucial in elderly patients with ACS because they have higher risk of mortality but, also, higher risk of bleeding or other side effects of currently recommended treatments. Compared to younger patients, older patients are admitted more frequently with NSTEMI and medical treatments or revascularization are commonly underused [25][26][25,26]. Current NSTEMI guidelines clearly state that interventional procedures for revascularization should be applied at any age [13]. Nonetheless, age is frequently reported as the variable most closely related to lower revascularization rates [27]. Of all the reasons postulated for the underuse of revascularization, the leading limitations might be the excess of bleeding complications or the lack of long-term benefit [28]. Bleeding complications have certainly increased in recent decades due to the incorporation of more potent antiplatelet and anticoagulant strategies [29]. In contrast, vascular access complications have decreased substantially with the generalization of radial access, especially in the elderly and high-bleeding risk patients [30][31][30,31]. The largest clinical trial involving elderly patients with NSTEMI, or unstable angina, was the After Eighty study that included 457 patients who were randomized to either an invasive or conservative treatment strategy [32]. After 1.5 years of follow-up, the invasive strategy was superior to a conservative strategy in reducing the primary endpoint, namely, a composite of myocardial infarction, urgent revascularization, stroke, or death. The primary endpoint was reduced by 47% using the invasive strategy (hazard ratio 0.53, 95% CI 0.41–0.69; p = 0.0001), although the benefit was lower in patients aged >85, and no differences in terms of bleeding complications were noted. It should be noted that in this trial, a strict conservative strategy was applied instead of a selective invasive strategy, with no coronary angiography performed in any patient assigned to this group. In 2020, the SENIOR-NSTEMI study was published, which was an observational study with 1976 NSTEMI patients aged >80 [33]. After propensity score matching, it showed that revascularization within the first 3 days of admission was associated to 32% reduction in all-cause mortality (hazard ratio: 0.68, 95% CI 0.55–0.84). This study had several limitations because it did not assess the effect of heart failure of index hospitalization on post-discharge prognosis, and heart failure incidence was not assessed taking all-cause mortality as a competing event [34][35][34,35].

Lastly, revascularization procedures could also be discussed. The use of drug-eluting stents has been generalized in percutaneous revascularization, and several trials have demonstrated their superiority compared to bare-metal stents also in the elderly [36]. Polymer-free drug-eluting stents have demonstrated to have a very low risk of stent thrombosis with short-term dual antiplatelet treatments [37], and this has also been demonstrated in second and third generations of drug-eluting stents [38]. Another important aspect is the relevance of the complete revascularization in this age group. Agra-Bermejo et al. observed in a propensity-score analysis of an observational cohort a long-term benefit in terms of mortality of complete vs. culprit-only revascularization in older patients with NSTEMI [39]. However, other studies showed controversial results [40][41][40,41]. Further randomized evidence is warranted to clarify the better strategy regarding complete revascularization in the older patient.

In conclusion, an invasive strategy with currently available technologies (radial access and newer generation drug-eluting stents) is safe and effective to improve outcomes in elderly patients with NSTEMI and, therefore, it should not be denied in this patient group.