Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by YINI HAN and Version 2 by Vicky Zhou.

Torreya grandis (T. grandis) is an old relict species within the family of Taxaceae that is endemic in China, often referred to as Chinese Torreya. It has been one of the most economically important tree species in the subtropical region of China.

- Torreya grandis

- nitrogen enrichment

- long-term fertilizer treatments

- phosphorus limitation

1. Introduction

The Kuaijishan Ancient Chinese Torreya Community was listed in China National Important Agricultural Heritage and Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems (GIAHS) in 2013 [1][2]. Trees in the community area are considered ‘living fossils’ because they originated from the application of grafting and artificial selection techniques in ancient China. Many of those trees are over one thousand years economic old but still sustain a high yield of seed production. The Chinese Torreya community is highly valued both ecologically (e.g., water and soil conservation, climate regulation, biodiversity maintaining) and economically (e.g., nuts, medicine, oil, and as an ornamental tree). As a result, the planting area of T. grandis has steadily increased in several provinces during the past three decades. However, the old Torreya plantation in the Kuaijishan Ancient Chinese Torreya Community is facing severe degradation due to nature aging, climate change, and inappropriate management, such as overfertilization.

Alternate bearing phenomenon loom large, due to the overexploitation of T. grandis seeds; to improve this, escalating amounts of chemical nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P) rich fertilizer have been applied by the local manager, without any scientific management guidance (e.g., supplying based on the demands of plants). N and P are key nutrients that play pivotal roles in controlling plant growth and litter decomposition, as well as in ecosystems’ biochemical cycles [3][4][5]. However, the indiscriminate use of chemical fertilizer (including quantity and proportion) has caused abnormally high concentrations of N and P to accumulate in the soil, which has severely stressed the terrestrial plants’ multiple physiological processes. Furthermore, the excessive use of chemical fertilizer has also generated serious adverse environmental consequences, such as non-point source pollution [6] and N-induced soil acidification (especially due to NH4+), both of which have been observed in multiple ecosystems [7][8][9]. It should be noted that soil acidification would change ecosystem biogeochemistry, accelerating cationic nutrient (such as Ca2+, Mg2+) leaching and thereby, reducing plant productivity in turn [10][11] and negatively affecting local biodiversity [12][13].

Under natural conditions, N input to an N-limited ecosystem (such as boreal forests) will improve net primary productivity (NPP) through a direct fertilizing effect on vegetation [14]. As a direct result from global change, N deposition in many regions of the world (i.e., United States, western Europe, and China) currently exceeds 10 kg N ha−1 yr−1, especially in tropical and subtropical areas of China [15][16],where over 80–120 kg N ha−1 yr−1 has been reported [17]. China has become one of the highest N deposition area, and N deposition has increased by approximately 60% over the past three decades [16]. A meta-analysis has reported an N saturation threshold of 50–60 kg ha−1 yr−1 across the entire terrestrial ecosystem [18]. Therefore, as N deposition levels continue to accelerate, N-limitation has been subsequently alleviated [19], and there is a high likelihood that the ecosystem is shifting to an N-enriched status [20]. Unlike N, which can be accumulated through biological fixation and increasing deposition, available soil P comes from slow parent mineral weathering and a low rate of atmospheric deposition from wildfires. Based on nutrient demand balance theory, excessive N input has been reported to not only disturb the balance in the biogeochemical cycles of essential plant nutrients [21][22][23], but also initiate P-limitation in forest ecosystems [24][25][26][27]. Fang et al. [28] reported N saturation in three subtropical sites and noted that P deficiency is becoming progressively more problematic. The anthropogenic alternation of regional P and N cycling has led to large areas of southern China forests shifting to human-induced P-limitation [27]. NPP/GPP has transformed from being N-limited to P-limited in many forest ecosystems [4][26][29][30].

Soil N and P availability, especially when combined with N deposition and/or external addition, can influence forest productivity and ecosystem processes [3][31]. Trees can keep leaf nutrient concentrations and their ratios stable by modulating the nutrients coming from branches, roots or senescent leaves [32][33]. Recently, foliar N and P concentration stoichiometry ratios (i.e., N:P, C:N, C:P) have been used to indicate soil N- and/or P-limitations on plant growth [24][34][35]. In addition, nutrient resorption [nitrogen (NRE) and/or phosphorus (PRE)] from senescing plant tissues and the proficiency of nutrient conservation [36], are also widely used as indicators in studies of nutrient cycling between plants and soil in fluctuating environments. Generally, nutrients would transfer from senescent leaf to trunk before falling off, thereby maintaining the plant nutrients at a favorable level. The NRE and PRE might depend on the type of nutrient limitation [37] and vary in response to the plant’s intrinsic genetic characteristics [38][39]. NRE/PRE is commonly employed to determine the relative limitation between N and P; NRE/PRE values > 1 imply a stronger N-limitation at the ecosystem scale [26]. However, previous studies predominantly focused on the effect of single N or P addition on leaf nutrients or resorption; thus, the effect of multiple nutrient addition on NRE and/or PRE in subtropical forests is not well understood.

Meanwhile, the relationship between plant P uptake and nutrient environmental supply is more comprehensive than N. Under intensive management, the long-term addition of balanced compound fertilizer may cause excess P in orchards, as plants generally require less P than N [40]. P is an essential element for nucleic acids and membrane lipids. Although P sensing and signaling are not fully understood, there appears to be a series of physiological processes in plants that are either stimulated or suppressed in response to P supply [41]. Unlike the immobile N in the plant cell wall, most leaf P is hydrolyzable and, therefore, more easily resorbed [42][43]. In fact, due to its indiscriminate uptake, greater variability of foliar P has been reported even in growth stages in which it is not needed [44]. Species in P-poor environments, such as subtropical evergreen trees, are equipped with a corresponding adaptation mechanism that makes them more susceptible to toxic eutrophication under excessive P addition [45].

At present, there is not even a clear relationship between N and P fertilization with economic benefit (such as seed yield) in our research area; furthermore, an excessive or unreasonable rate of fertilizer consumption faces both increasing economic investments and the deterioration of the soil’s physical and chemical properties, let alone its internal nutrient influence mechanism. Thus, it is critical to determine the optimal amount of fertilizer necessary to achieve ideal growth. A comprehensive understanding of fertilizer impact on crop quantity and soil quality is critical for improving fertilizer treatment strategies in economic consideration and maintaining a healthy soil environment.

2. Fertilization Failed to Make Positive Effects on Torreya grandis in Severe N-Deposition Subtropics

2.1. Effects of Fertilizer on Soil Condition

Long-term N deposition and fertilization could elevate soil nutrient concentration beyond the demand of the plant, altering the soil nutrient cycles [46]. Because most soils in subtropical areas are severely acidic, improper and excessive use of fertilizers could further deteriorate soil physical, chemical, and biological properties, especially aggravating soil acidification and soil hardening. Decreases in soil pH caused by fertilizer will likely reduce soil microbial and enzyme activities, which subsequently reduces organic matter mineralization and ultimately reduces “chemical facilitation” [47], which presented obviously with intensifying N fertilization in this study.

2.2. Effect of Fertilizer on Plant C, N, and P Stoichiometry

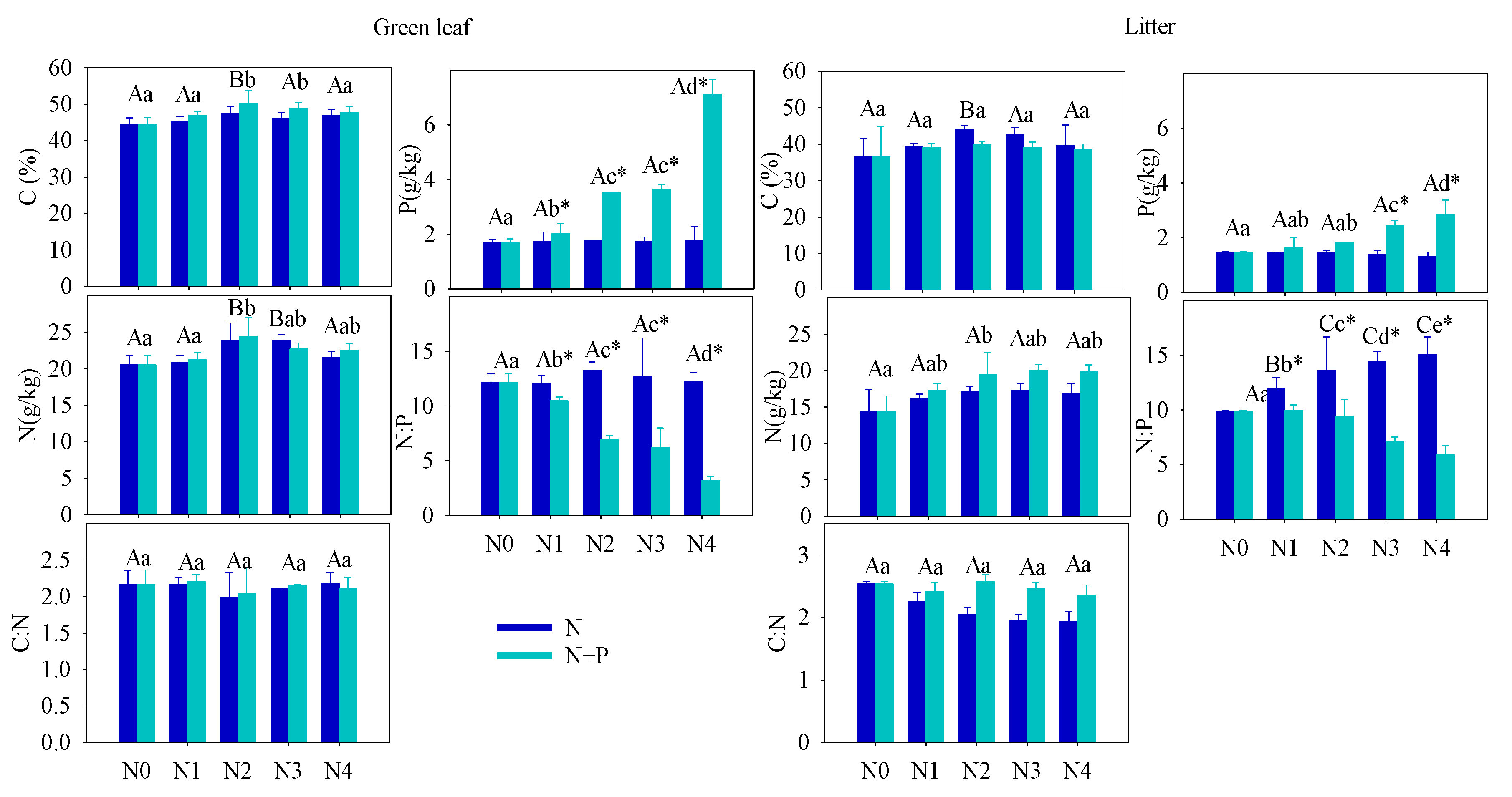

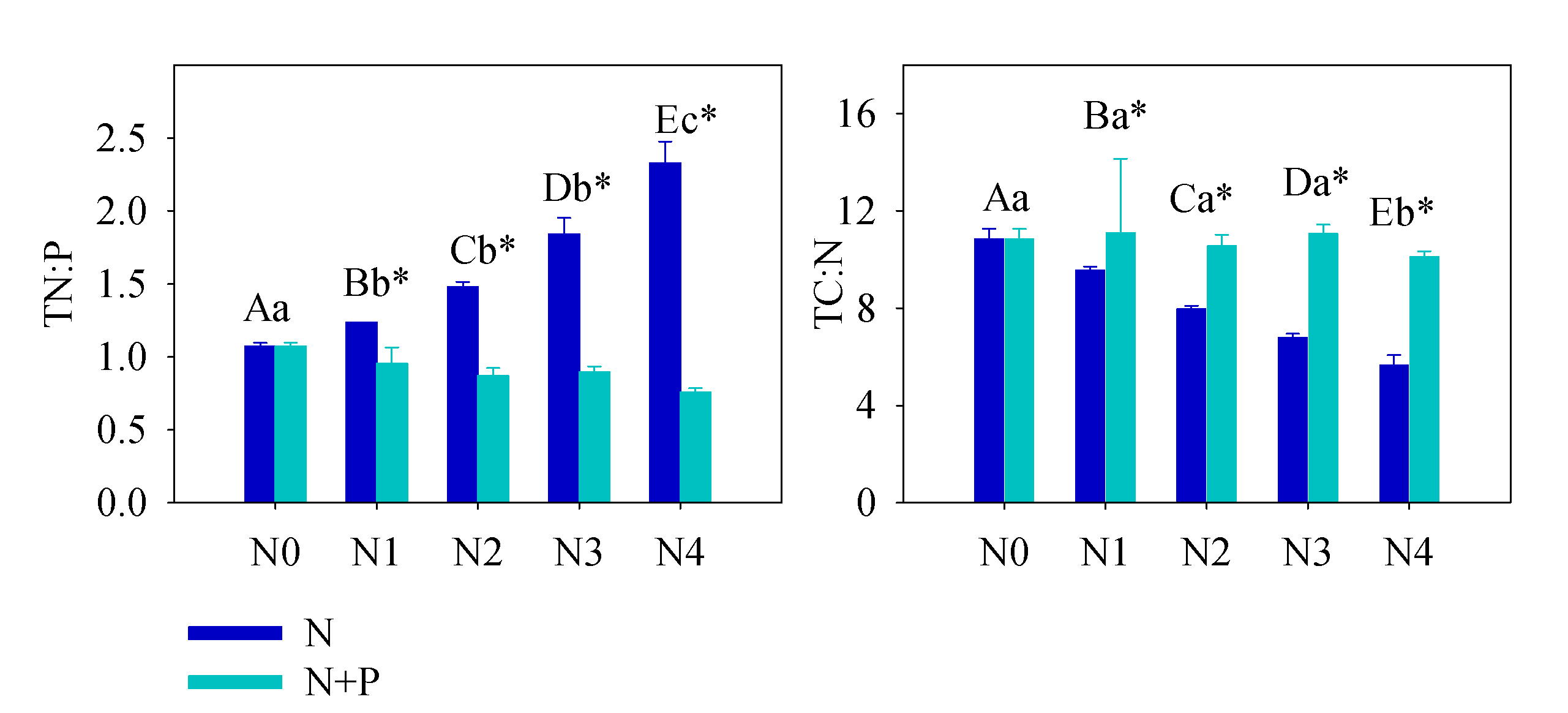

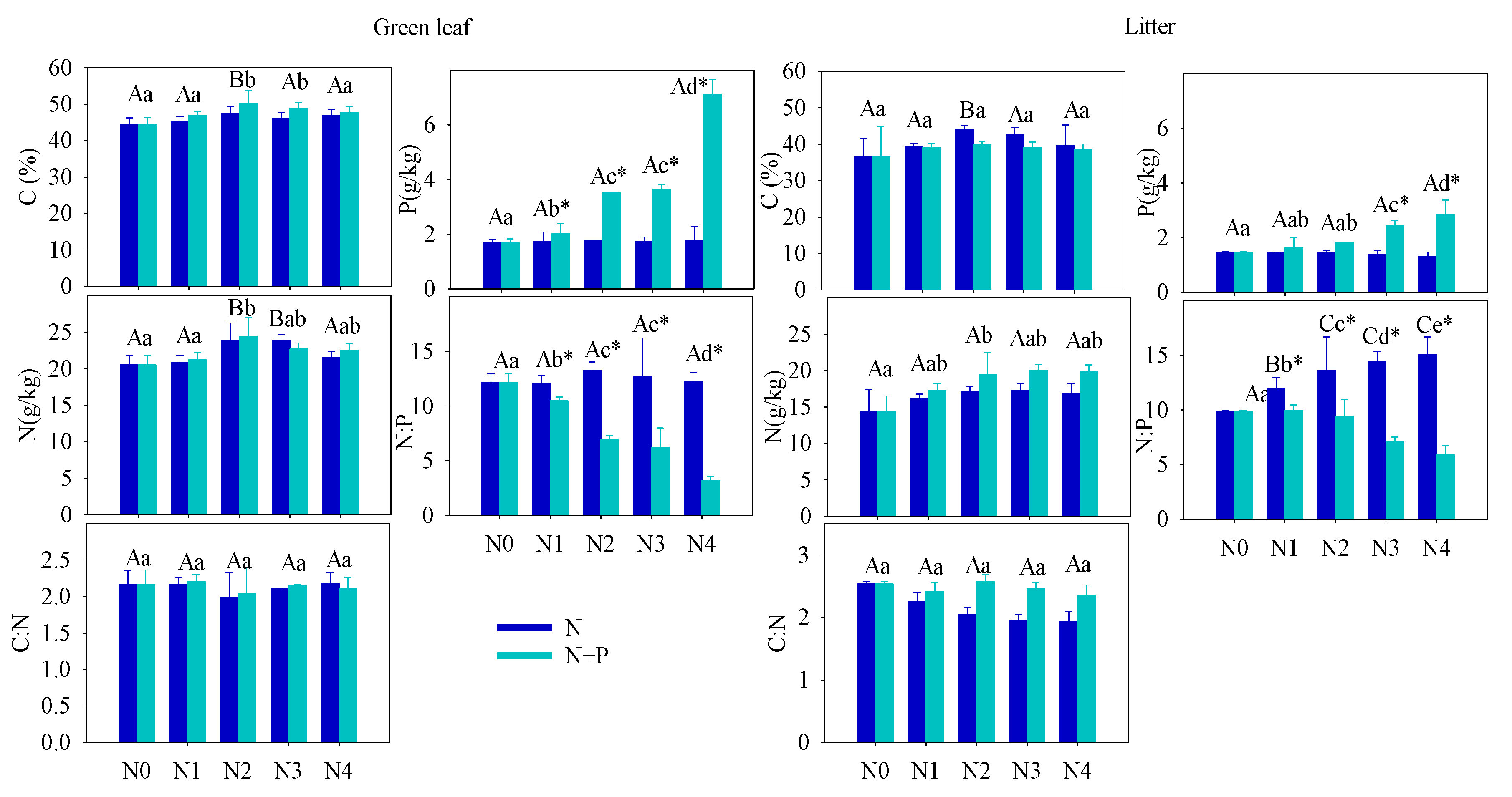

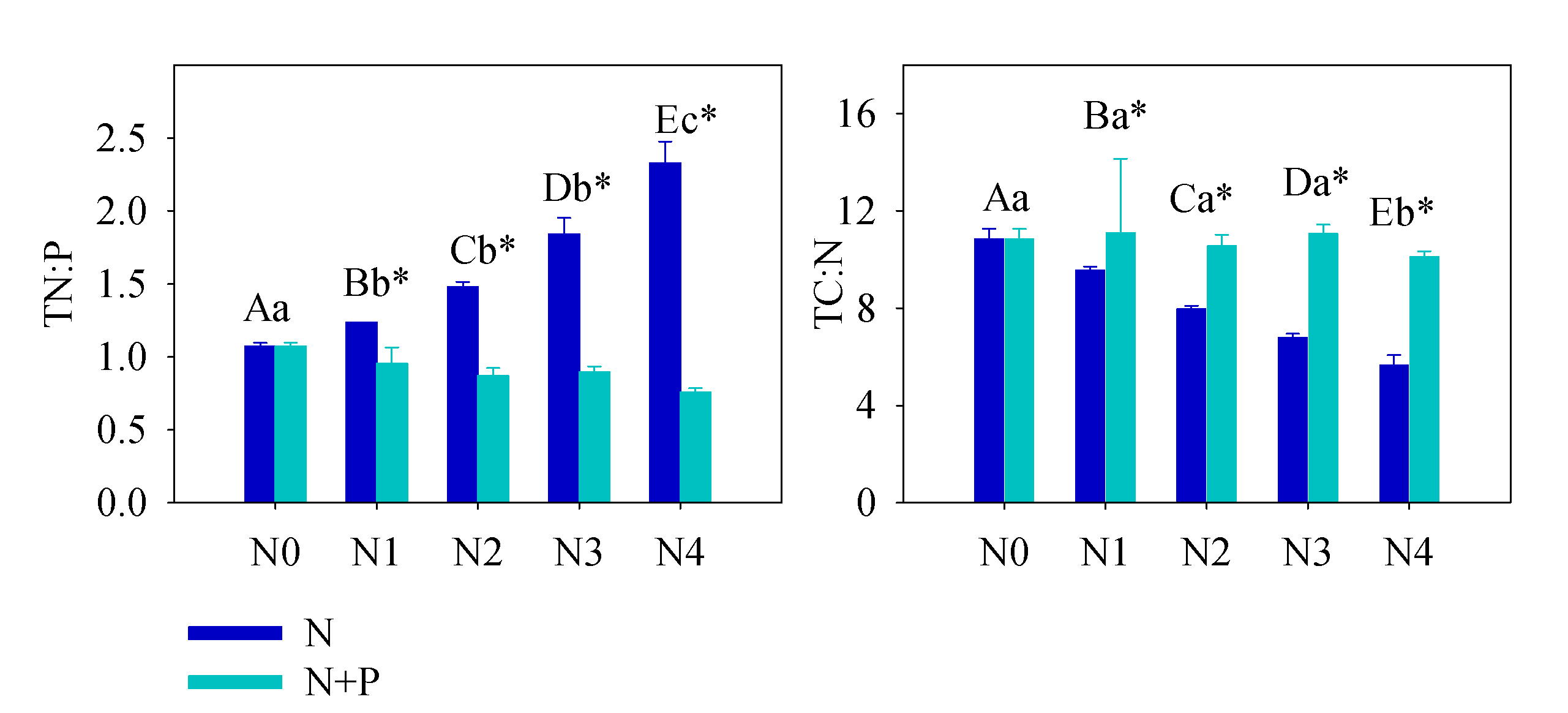

One of the primary goals of this research is to evaluate whether T. grandis requires extra fertilization or whether adding additional nutrients can improve seed production. In the present study, fertilization tended to increase the foliar nutrients ([C], [N], [P]), but only the increase in [P] was statistically significant in the N + P addition scenario. The steady foliar [N] under increasing fertilization may indicate diminished N-limitation to plant growth, which can be explained by a plant behavior developed from adjusting to nutrient-abundant environments. A significant increase of leaf [P] in N + P scenario resulted in a distinct decrease in the C:P and N:P ratios. According to the growth-rate hypothesis, plant invests more phosphorus to RNA for rapid protein synthesis in fast-growing organisms [48]. Hence, the opposite condition, high leaf [P], indicated a low-growing condition of T. grandis under high fertilization, which was confirmed by the statistical results of annual shoots.

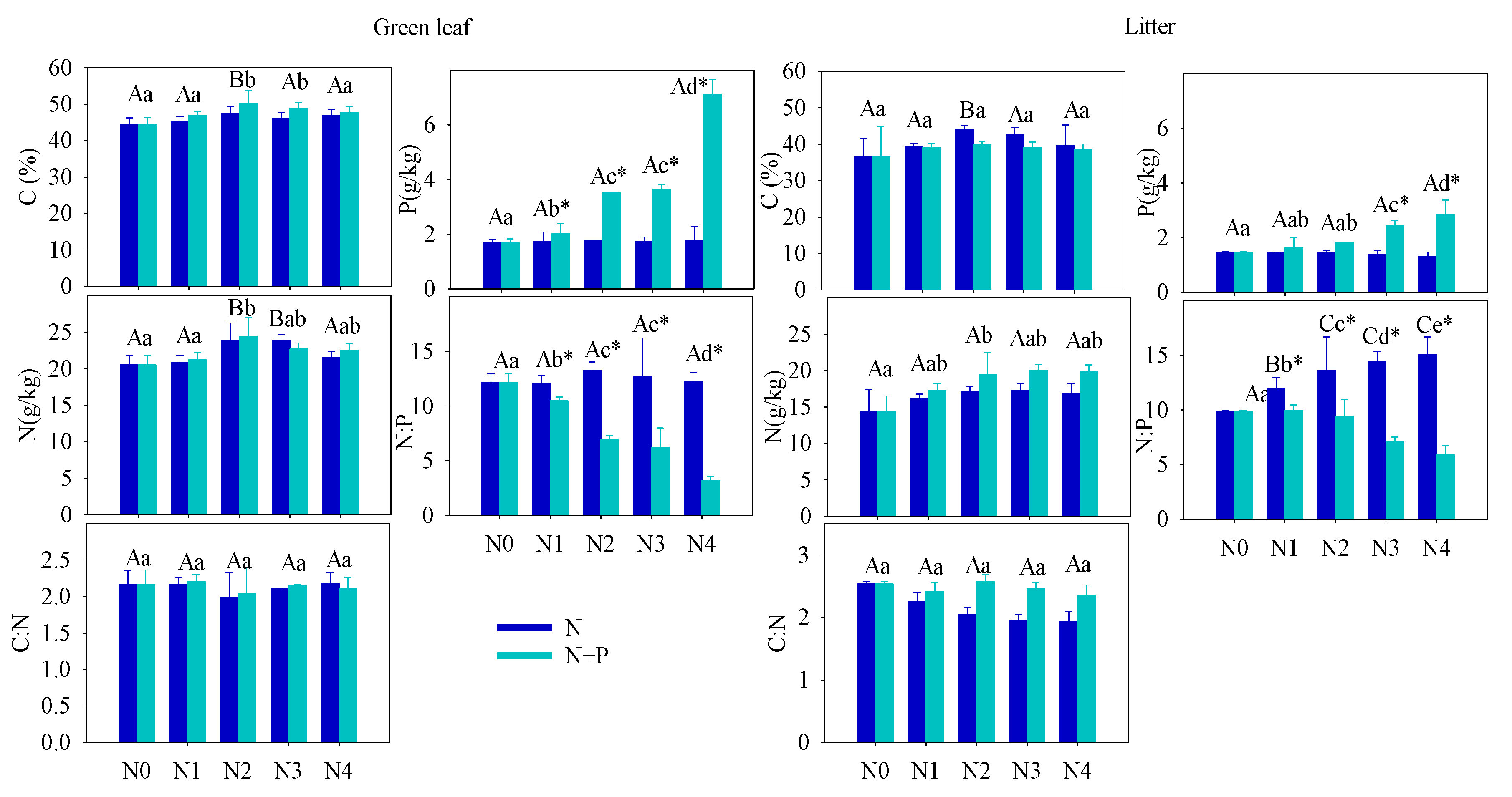

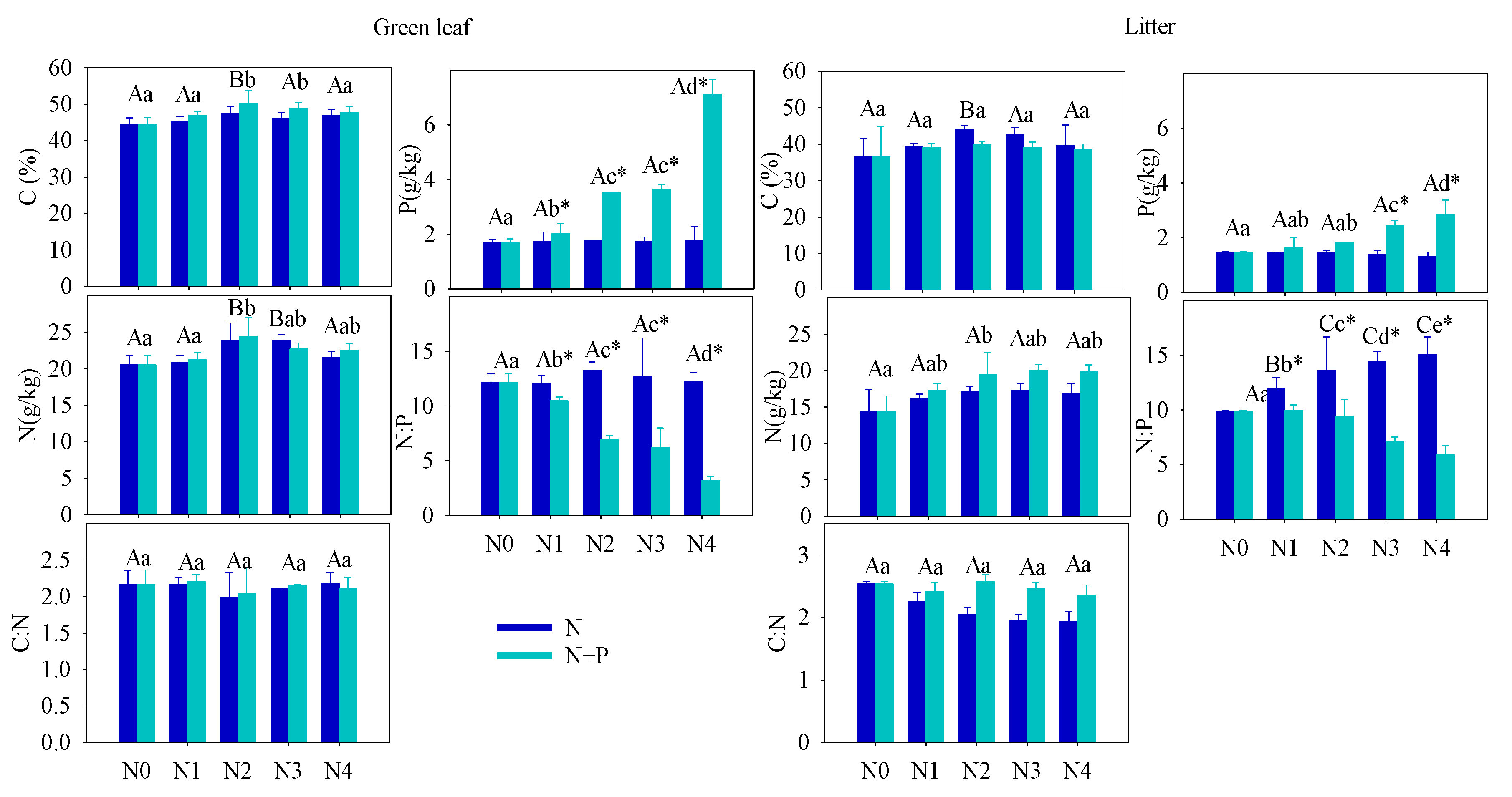

The soil nutrient pool (TN, TP, HN, and SOC), under long-term fertilizer treatment, was much higher than that in other subtropical areas [49][50]. Long-term soil nutrient enrichment resulted in much higher T. grandis foliar nutrient (N and P) contents than the average values of 753 terrestrial species [51] and other subtropical evergreen trees [52]. Due to the different N and P utility patterns in physiological processes, regardless of species and site fertilizer supply, plants can store a greater percentage of inorganic P than N. Thus, with increasing fertilizer addition, foliage accumulated more P than N [44]. It was also observed that some plant species growing in P-limited environments might not downregulate P uptake when a higher supply of P is available [44][53][54]. When the environment P supply shifts from P-limited to non-limited condition, the plants may undergo an excessive P uptake, even to saturated or toxic levels. Hence, foliar [P] usually displays a much higher variation after fertilizer treatments. Therefore, it is not surprised that the foliar [P] nearly doubled after a high fertilizer treatment compared to the control group (Figure 14). Given the generally low bioavailability of P in subtropical soils, T. grandis may have developed an efficient mechanism to take up and accumulate P in response to the strong selective pressure [55][56]. Unlike previous studies [21][57][58][59][60][61][62], leaf [N] of T. grandis didn’t change much in response to the increasing soil [N] availability, which implied that fertilizer treatments had no effect on T. grandis N absorption (Figure 23). In this scenario, relatively stable leaf [C] and [N], but increased leaf [P], led to opposite trends between C:P and N:P and soil nutrient content (Figure 23). Therefore, our findings answered the first question, that long-term fertilization, combined with increasing nitrogen deposition, results in a N-enriched environment. This result also confirms that N-limitation has been generally alleviated in this subtropical forest; while P-limitation in the study area was aggravated by N enrichment [51][60][61].

Figure 13. Effect Sof different fertilizer treatments on the green (left) and senescent (right) leaf nutrient content ([C], [N] and [P]) and C:N, N:P ratiosil total N:P and total C:N under different treatment. Error bars refer to ±1 standard error (different capital letters indicate a significant difference among factors under N addition only; lowercase letters indicate a significant difference among factors under N + P addition; * indicate a significant difference between two fertilization scenarios under same addition intensity, p < 0.05).

Figure 24. SEffect oil total N:P and total C:N under different treatmentf different fertilizer treatments on the green (left) and senescent (right) leaf nutrient content ([C], [N] and [P]) and C:N, N:P ratios. Error bars refer to ±1 standard error (different capital letters indicate a significant difference among factors under N addition only; lowercase letters indicate a significant difference among factors under N + P addition; * indicate a significant difference between two fertilization scenarios under same addition intensity, p < 0.05).

2.3. Effect of Fertilizer on Plant Nutrient Resorption

2.3. Effect of Fertilizer on Plant Nutrient Resorption

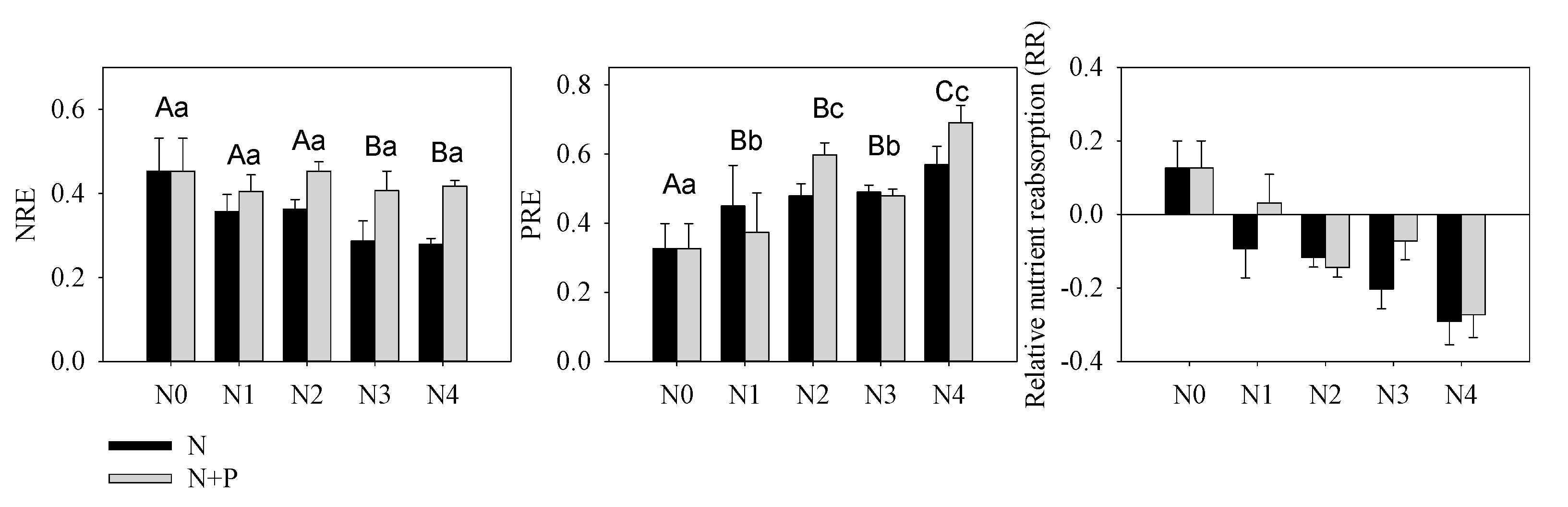

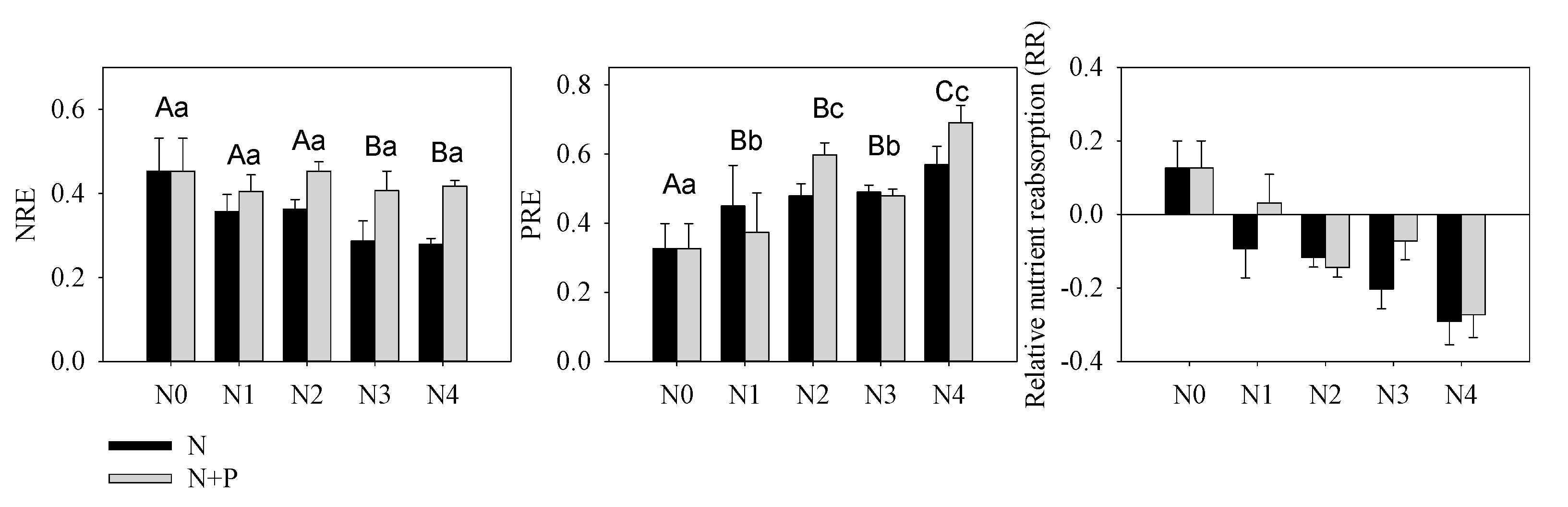

Acquisition (root uptake) and conservation (resorption from senescent tissue) are two important biological strategies for plants to maintain balanced nutrition where soil nutrients are deficient. These processes are also important in cycling nutrients between the soil and plants [63]. Choosing between alternative strategies for plants depends on the cost (time and energy) of each process and the species characteristics. Short-term experiments have demonstrated that, generally, plants will reduce nutrient utilization efficiency when the surrounding nutrient availability increases [64], while the relationship between foliar resorption and soil nutrient concentration is not consistent [34][65][66]. Nutrient resorption was another important index indicating environmental nutrient deficiency or not. Our results indicated a constant or slight decreased NRE, which further verified our supposition concerning N enrichment in these orchards (Figure 35). According to nutrient balance theory, N addition aggravated P-limitation that was illustrated by increasing PRE. However, increased P migration from senescent leaf to green leaf (PRE) in response to increasing N + P fertilizer supply conflicts with the negative correlation between fertilizer treatment and nutrient resorption [64]. This kind of counterintuitive result has been observed in a single-resource conservation standpoint in previous studies [67][68]; yet multiple-element theory much more appropriately explains variability in foliar nutrient resorption [60]. Based on a Pearson correlation analysis, we found that green leaf [P] was not related to soil [AP], but it was highly correlated with soil N content. It should be noted that the root system can directly uptake inorganic nutrients (AP and HN) and therefore plays a more important role in nutrient absorption than organic nutrients. This inorganic nutrient preference may help explain the absence of a common trend in studies comparing P resorption to soil P availability [34][66]. Herein, although the soil and leaves were characterized by a higher [P] compared to other studies of evergreen trees [69], excess N addition was responsible for the amplified P-limitation (Figure 35), which subsequently elevated leaf P uptake directly [70][71].

Figure 35. Nutrients resorption efficiency of N (NRE), P (PRE) and relative nutrient resorption (RR = NRE − PRE) of T. grandis under different fertilizer treatment scenarios. The lowercase letters indicate a significant difference among treatments, p < 0.05.

3. Conclusions

Long-term fertilizer treatments increased soil N and P significantly in T. grandis orchards, which increased leaf N and P concentrations, but there was no obvious positive impact on T. grandis growth but only a negative impact on seed yield under heavy fertilizer application. Herein, N enrichment was indicated by stable and decoupling relationships between the soil and leaf [N]. Leaf [P] was highly correlated with soil [N], and N enrichment amplified the physiological P limitation (deficiency). Excessive N addition interfered T. grandis’s sensibility to P availability in this N-enrichment area, which is indicated by increasing PRE with both modes of fertization intensity. Therefore, leaf [P] or the N:P ratio may not reflect the actual demands of the plant under the P addition conditions herein. Furthermore, large amount of fertilizer application might waste resources and alter soil physicochemical properties (e.g., soil acidification). Decreasing fertilizer application should be taken into consideration to accomplish the sustainable development of the orchard ecosystems.

References

- FAO. Kuaijishan Ancient Chinese Torreya, China. Available online: http://www.fao.org/giahs/giahsaroundtheworld/designated-sites/asia-and-the-pacific/kuajishan-ancient-chinese-torreya/en (accessed on 10 May 2020).

- MOA. Available online: http://www.moa.gov.cn/ztzl/zywhycsl/dypzgzywhyc/ (accessed on 10 May 2020).

- Finzi, A.C.; Austin, A.; Cleland, E.E.; Frey, S.; Houlton, B.Z.; Wallenstein, M.D. Responses and feedbacks of coupled biogeochemical cycles to climate change: Examples from terrestrial ecosystems. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2011, 9, 61–67.

- Penuelas, J.; Poulter, B.; Sardans, J.; Ciais, P.; van der Velde, M.; Bopp, L.; Boucher, O.; Godderis, Y.; Hinsinger, P.; Llusia, J.; et al. Human-induced nitrogen-phosphorus imbalances alter natural and managed ecosystems across the globe. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 1–10.

- You, C.; Wu, F.; Yang, W.; Xu, Z.; Tan, B.; Zhang, L.; Yue, K.; Ni, X.; Li, H.; Chang, C. Does foliar nutrient resorption regulate the coupled relationship between nitrogen and phosphorus in plant leaves in response to nitrogen deposition? Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 645, 733–742.

- Sun, Y.; Hu, R.; Zhang, C. Does the adoption of complex fertilizers contribute to fertilizer overuse? Evidence from rice production in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 219, 677–685.

- Zhu, Z.; Chen, D. Nitrogen fertilizer use in China–Contributions to food production, impacts on the environment and best management strategies. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosystems 2002, 63, 117–127.

- Fernández-Escobar, R.; Marin, L.; Sánchez-Zamora, M.; García-Novelo, J.; Molina-Soria, C.; Parra, M. Long-term effects of N fertilization on cropping and growth of olive trees and on N accumulation in soil profile. Eur. J. Agron. 2009, 31, 223–232.

- Zhao, Q.; Zeng, D.-H. Nitrogen addition effects on tree growth and soil properties mediated by soil phosphorus availability and tree species identity. For. Ecol. Manag. 2019, 449, 117478.

- Dai, Z.; Zhang, X.; Tang, C.; Muhammad, N.; Wu, J.; Brookes, P.C.; Xu, J. Potential role of biochars in decreasing soil acidification-A critical review. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 581, 601–611.

- Zhang, Y.; He, X.; Liang, H.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, C.; Shi, X. Long-term tobacco plantation induces soil acidification and soil base cation loss. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 5442–5450.

- Peppler-Lisbach, C.; Stanik, N.; Konitz, N.; Rosenthal, G. Long-term vegetation changes inNardusgrasslands indicate eutrophication, recovery from acidification, and management change as the main drivers. Appl. Veg. Sci. 2020, 23, 508–521.

- Phoenix, G.K.; Emmett, B.A.; Britton, A.J.; Caporn, S.J.M.; Dise, N.B.; Helliwell, R.; Jones, L.; Leake, J.R.; Leith, I.D.; Sheppard, L.J.; et al. Impacts of atmospheric nitrogen deposition: Responses of multiple plant and soil parameters across contrasting ecosystems in long-term field experiments. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2012, 18, 1197–1215.

- Lebauer, D.; Treseder, K. Nitrogen Limitation of Net Primary Productivity in Terrestrial Ecosystems is Globally Distributed. Ecology 2008, 89, 371–379.

- Meunier, C.L.; Gundale, M.J.; Sánchez, I.S.; Liess, A. Impact of nitrogen deposition on forest and lake food webs in nitrogen-limited environments. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2016, 22, 164–179.

- Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Han, W.; Tang, A.; Shen, J.; Cui, Z.; Vitousek, P.; Erisman, J.W.; Goulding, K.; Christie, P.; et al. Enhanced nitrogen deposition over China. Nature 2013, 494, 459.

- Yu, L.; Zhu, J.; Mulder, J.; Dörsch, P. Multiyear dual nitrate isotope signatures suggest that N-saturated subtropical forested catchments can act as robust N sinks. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2016, 22, 3662–3674.

- Tian, D.; Wang, H.; Sun, J.; Niu, S. Global evidence on nitrogen saturation of terrestrial ecosystem net primary productivity. Environ. Res. Lett. 2016, 11, 024012.

- Tao, L.; Hunter, M.D. Does anthropogenic nitrogen deposition induce phosphorus limitation in herbivorous insects? Glob. Chang. Biol. 2012, 18, 1843–1853.

- Yu, Q.; Duan, L.; Yu, L.; Chen, X.; Si, G.; Ke, P.; Ye, Z.; Mulder, J. Threshold and multiple indicators for nitrogen saturation in subtropical forests. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 241, 664–673.

- Ferretti, M.; Marchetto, A.; Arisci, S.; Bussotti, F.; Calderisi, M.; Carnicelli, S.; Cecchini, G.; Fabbio, G.; Bertini, G.; Matteucci, G. On the tracks of Nitrogen deposition effects on temperate forests at their southern European range—An observational study from Italy. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2015, 20, 3423–3438.

- Sardans, J.; Alonso, R.; Janssens, I.; Carnicer, J.; Vereseglou, S.; Rillig, M.C.; Fernández-Martínez, M.; Sanders, T.G.M.; Peñuelas, J. Foliar and soil concentrations and stoichiometry of nitrogen and phosphorous across European Pinus sylvestris forests: Relationships with climate, N deposition and tree growth. Funct. Ecol. 2016, 30, 676–689.

- Gilliam, F.S.; Billmyer, J.H.; Walter, C.A.; Peterjohn, W.T. Effects of excess nitrogen on biogeochemistry of a temperate hardwood forest: Evidence of nutrient redistribution by a forest understory species. Atmos. Environ. 2016, 146, 261–270.

- Güsewell, S. N:P ratios in terrestrial plants: Variation and functional significance. New Phytol. 2004, 164, 243–266.

- Vitousek, P.; Porder, S.; Houlton, B.; Chadwick, O. Terrestrial phosphorus limitation: Mechanisms, implications, and nitrogen-phosphorus interactions. Ecol. Appl. A Publ. Ecol. Soc. Am. 2010, 20, 5–15.

- Du, E.; Terrer, C.; Pellegrini, A.F.; Ahlström, A.; van Lissa, C.J.; Zhao, X.; Xia, N.; Wu, X.; Jackson, R.B. Global patterns of terrestrial nitrogen and phosphorus limitation. Nat. Geosci. 2020, 13, 221–226.

- Du, E.; Vries, W.D.; Han, W.; Liu, X.; Yuan, J. Imbalanced phosphorus and nitrogen deposition in China’s forests. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2016, 16, 8571–8579.

- Fang, X.-M.; Zhang, X.-L.; Chen, F.-S.; Zong, Y.-Y.; Bu, W.-S.; Wan, S.-Z.; Luo, Y.; Wang, H. Phosphorus addition alters the response of soil organic carbon decomposition to nitrogen deposition in a subtropical forest. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2019, 133, 119–128.

- Zhan, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Li, W.; Bai, Y. Nitrogen enrichment alters plant N: P stoichiometry and intensifies phosphorus limitation in a steppe ecosystem. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2017, 134, 21–32.

- Du, E.; van Doorn, M.; de Vries, W. Spatially divergent trends of nitrogen versus phosphorus limitation across European forests. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 771, 145391.

- Elser, J.J.; Sterner, R.; Gorokhova, E.; Fagan, W.F.; Markow, T.; Coter, J.; Harrison, J.; Hobbie, S.; Odell, G.M.; Weider, L. Biological Stoichiometry from Genes to Ecosystems. Ecol. Lett. 2000, 3, 540–550.

- Yan, Z.; Li, P.; Chen, Y.; Han, W.; Fang, J. Nutrient allocation strategies of woody plants: An approach from the scaling of nitrogen and phosphorus between twig stems and leaves. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 1–9.

- Cernusak, L.A.; Winter, K.; Turner, B.L. Leaf nitrogen to phosphorus ratios of tropical trees: Experimental assessment of physiological and environmental controls. New Phytol. 2010, 185, 770–779.

- Aerts, R.; Chapin III, F.S. The mineral nutrition of wild plants revisited: A re-evaluation of processes and patterns. Adv. Ecol. Res. 1999, 30, 1–67.

- Koerselman, W.; Meuleman, A.F. The vegetation N: P ratio: A new tool to detect the nature of nutrient limitation. J. Appl. Ecol. 1996, 33, 1441–1450.

- Lin, Y.-M.; Liu, X.-W.; Zhang, H.; Fan, H.-Q.; Lin, G.-H. Nutrient conservation strategies of a mangrove species Rhizophora stylosa under nutrient limitation. Plant Soil 2010, 326, 469–479.

- Güsewell, S. Nutrient resorption of wetland graminoids is related to the type of nutrient limitation. Funct. Ecol. 2005, 19, 344–354.

- Silla, F.; Escudero, A. Uptake, demand and internal cycling of nitrogen in saplings of Mediterranean Quercus species. Oecologia 2003, 136, 28–36.

- Sadanandan Nambiar, E.K.; Fife, D.N. Nutrient retranslocation in temperate conifers. Tree Physiol. 1991, 9, 185–207.

- Macy, P. The quantitative mineral nutrient requirements of plants. Plant Physiol. 1936, 11, 749.

- Fang, Z.; Shao, C.; Meng, Y.; Wu, P.; Chen, M. Phosphate signaling in Arabidopsis and Oryza sativa. Plant Sci. 2009, 176, 170–180.

- McGroddy, M.E.; Daufresne, T.; Hedin, L.O. Scaling of C: N: P stoichiometry in forests worldwide: Implications of terrestrial redfield-type ratios. Ecology 2004, 85, 2390–2401.

- Ågren, G.I. Stoichiometry and nutrition of plant growth in natural communities. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2008, 39, 153–170.

- Ostertag, R. Foliar nitrogen and phosphorus accumulation responses after fertilization: An example from nutrient-limited Hawaiian forests. Plant Soil 2010, 334, 85–98.

- Musick, H.B. Phosphorus toxicity in seedlings of Larrea divaricata grown in solution culture. Bot. Gaz. 1978, 139, 108–111.

- Huang, J.; Wang, X.; Yan, E. Leaf nutrient concentration, nutrient resorption and litter decomposition in an evergreen broad-leaved forest in eastern China. For. Ecol. Manag. 2007, 239, 150–158.

- Yang, H. Effects of nitrogen and phosphorus addition on leaf nutrient characteristics in a subtropical forest. Trees 2018, 32, 383–391.

- Matzek, V.; Vitousek, P.M. N:P stoichiometry and protein:RNA ratios in vascular plants: An evaluation of the growth-rate hypothesis. Ecol. Lett. 2009, 12, 765–771.

- Zhang, Q.F.; Xie, J.S.; Lyu, M.K.; Xiong, D.C.; Wang, J.; Chen, Y.M.; Li, Y.Q.; Wang, M.K.; Yang, Y.S. Short-term effects of soil warming and nitrogen addition on the N:P stoichiometry of Cunninghamia lanceolata in subtropical regions. Plant Soil 2017, 411, 395–407.

- Kou, L.; Wang, H.; Gao, W.; Chen, W.; Yang, H.; Li, S. Nitrogen addition regulates tradeoff between root capture and foliar resorption of nitrogen and phosphorus in a subtropical pine plantation. Trees 2016, 31, 77–91.

- Han, W.; Fang, J.; Guo, D.; Zhang, Y. Leaf nitrogen and phosphorus stoichiometry across 753 terrestrial plant species in China. New Phytol. 2005, 168, 377–385.

- Tang, X.; Zhao, X.; Bai, Y.; Tang, Z.; Wang, W.; Zhao, Y.; Wan, H.; Xie, Z.; Shi, X.; Wu, B.; et al. Carbon pools in China’s terrestrial ecosystems: New estimates based on an intensive field survey. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 4021–4026.

- Shane, M.; Lambers, H. Phosphorus nutrition of Australian Proteaceae and Cyperaceae: A strategy on old landscapes with prolonged oceanically buffered climates. South Afr. J. Bot. 2007, 73, 274–275.

- Standish, R.; Stokes, B.; Tibbett, M.; Hobbs, R. Seedling response to phosphate addition and inoculation with arbuscular mycorrhizas and the implications for old-field restoration in Western Australia. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2007, 61, 58–65.

- Ingestad, T. Towards optimum fertilization. Ambio 1974, 3, 49–54.

- Chapin, F.S., III; Schulze, E.; Mooney, H.A. The ecology and economics of storage in plants. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1990, 21, 423–447.

- Mulligan, D.; Sands, R. Dry matter, phosphorus and nitrogen partitioning in three Eucalyptus species grown under a nutrient deficit. New Phytol. 1988, 109, 21–28.

- Zhang, R.; Zhao, Y.; Lin, J.; Hu, Y.; Hänninen, H.; Wu, J. Biochar application alleviates unbalanced nutrient uptake caused by N deposition in Torreya grandis trees and seedlings. For. Ecol. Manag. 2019, 432, 319–326.

- Huang, Z.; Liu, B.; Davis, M.; Sardans, J.; Peñuelas, J.; Billings, S. Long-term nitrogen deposition linked to reduced water use efficiency in forests with low phosphorus availability. New Phytol. 2016, 210, 431–442.

- Wang, M.; Murphy, M.T.; Moore, T.R. Nutrient resorption of two evergreen shrubs in response to long-term fertilization in a bog. Oecologia 2014, 174, 365–377.

- See, C.R.; Yanai, R.D.; Fisk, M.C.; Vadeboncoeur, M.A.; Quintero, B.A.; Fahey, T.J. Soil nitrogen affects phosphorus recycling: Foliar resorption and plant–soil feedbacks in a northern hardwood forest. Ecology 2015, 96, 2488–2498.

- Allen, A.P.; Gillooly, J.F. Towards an integration of ecological stoichiometry and the metabolic theory of ecology to better understand nutrient cycling. Ecol. Lett. 2009, 12, 369–384.

- Killingbeck, K.T. The terminological jungle revisited: Making a case for use of the term resorption. Oikos 1986, 46, 263–264.

- Yuan, Z.Y.; Chen, H.Y.H. Negative effects of fertilization on plant nutrient resorption. Ecology 2015, 96, 373–380.

- Yuan, Z. Decoupling of nitrogen and phosphorus in terrestrial plants associated with global changes. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2015, 5, 465–469.

- Aerts, R. Nutrient resorption from senescing leaves of perennials: Are there general patterns? J. Ecol. 1996, 597–608.

- Boerner, R.E. Seasonal nutrient dynamics, nutrient resorption, and mycorrhizal infection intensity of two perennial forest herbs. Am. J. Bot. 1986, 73, 1249–1257.

- Sabaté, S.; Sala, A.; Gracia, C.A. Nutrient content in Quercus ilex canopies: Seasonal and spatial variation within a catchment. Plant. Soil 1995, 168, 297–304.

- Tang, Z.; Xu, W.; Zhou, G.; Bai, Y.; Li, J.; Tang, X.; Chen, D.; Liu, Q.; ma, W.; Xiong, G.; et al. Patterns of plant carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus concentration in relation to productivity in China’s terrestrial ecosystems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 4033–4038.

- Agüero, M.L.; Puntieri, J.; Mazzarino, M.J.; Grosfeld, J.; Barroetaveña, C. Seedling response of Nothofagus species to N and P: Linking plant architecture to N/P ratio and resorption proficiency. Trees 2014, 28, 1185–1195.

- Tian, D.; Reich, P.B.; Chen, H.Y.; Xiang, Y.; Luo, Y.; Shen, Y.; Meng, C.; Han, W.; Niu, S. Global changes alter plant multi-element stoichiometric coupling. New Phytol. 2019, 221, 807–817.

More