Teacher agency plays a critical role in sustaining early career teachers’ professional development. Teachers who are of proactive agency can stay true to themselves in seeking career development. Teachers who exercise proactive agency are more likely to regard themselves as a member of “a meaningful profession”, rather than doing “just a job” (p. 149). Teacher agency strengthens the teachers’ commitment to develop themselves as teachers. To provide implications for early career teachers’ professional development, it is essential to explore what shapes teachers’ enactment of agency, including resistance, ambivalence, and proactivity, and to examine the intricate relationship between teacher agency and identity commitment.

- early career ESL teachers

- teacher agency

- teacher identity

1. Teacher Agency

Teacher agency was described as the teachers’ capacity to “critically shape their responses to problematic situations” [1] (p. 11). As argued by Biesta and Tedder [2], the notion of agency suggests that “actors always act

[italics in the original] an environment rather than in an environment” (p. 137); the achievement of agency results from “the interplay of individual efforts, available resources and contextual and structural ‘factors’ as they come together in particular and, in a sense, always unique situations” (p. 137). Priestley, Biesta, and Robinson [3] formulated an ecological model for understanding teacher agency. This model of teacher agency includes the following three dimensions: iterational (i.e., teacher agency arises from teachers’ accumulated teacher experiences, and previous patterns of thoughts and actions), practical-evaluative (i.e., teachers can make practical judgements based on an evolving situation), and projective dimension (i.e., teachers can be motivated by an intentional act of creating a future). The above definitions suggest that agency refers to the agents’ actions in producing effects or fostering the capacity to act and make changes. The agent possesses the capacity to make choices based on his/her intentions and purposes, while, at the same time, is “reflexive and creative and can act counter to societal constraints as well as with societal possibilities” [4] (p. 197).

Teacher agency is important, as professional development for teachers has been something “for teachers, by teachers” [5] (p. 250). Teachers often demonstrate different degrees of teacher agency. One important reason is the fact that teachers enter the profession with different backgrounds and, most importantly, their communities may afford different degrees of autonomy in learning to teach [6]. In addition, when exploring teacher agency, we also need to consider teachers’ beliefs, their desires to set goals, and their knowledge of classroom pedagogy [7]. Teacher agency is an essential element in determining teachers’ efforts to confront, resist, and work out pedagogical conflicts. The exploration of teacher agency is particularly important for early career teachers, as they are in the early stage of being enabled and constrained by their social and institutional environment. Although early career teachers are expected to enact agency for professional development, they experience disappointments and challenges during their initial years of teaching [8].

2. Teacher Identity

Identity is a product of the volatile, fluctuating, and fragmental natures of the “self” [9] (p. 8). From the perspective of communities of practice, identity is a process that is established and maintained through negotiations within social situations, or social roles [10]. An awareness of identity provides a sense of continuity, enabling individuals to differentiate between the self and others [11]. A common understanding about identity is that institutional or social contexts in which individuals are situated, can reframe their identity trajectory [12]. Thus, we interpret individual teachers’ identity within their professional histories and institutional contexts, and explore the interplay between individuals and the contexts.

Teacher identity formation is a process wherein teachers engage in building their own ways to act similarly to teacher, and negotiate among multiple identities that are constantly shaped, reshaped, and adapted to the figured world [13]. Related to this, teacher identity is altered by “teaching context, experience, and biography” [14] (p. 761). Through an ongoing acquisition of knowledge and teaching, teachers construct and enact their identities, and modify their mental images to align with reality and realistic expectations [15]. The early career phase is described as “a tumultuous time of transition” for novice teachers [16] (p. 91). Therefore, teacher identity cannot be simply understood as teachers’ perceptions of themselves as teachers [17]. It can be operationalized as dynamic, discontinuous, and multi-faceted [18]. Early career teachers may confront school cultures that discourage innovation [19]. Hence, they may encounter identity conflicts.

3. A Proposed Framework on Agency and Identity

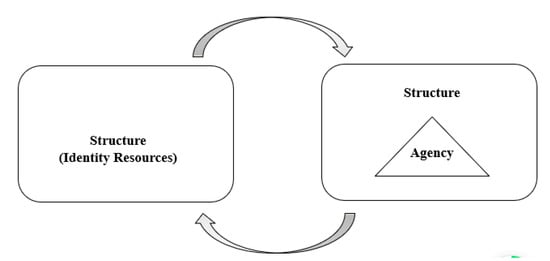

Early career teachers have to spend a disproportionate amount of time and effort in keeping up with the minimum requirements and responsibility [20]. Schaefer [21] suggests a need to examine the problems that influence teacher development, through focusing on individual teachers, including teaching experiences, educational background, and exploring the organizational contexts in which teachers work. Teachers’ professional commitments, although oriented towards the future, develop out of prior experience, as well as contextual conditions. One question for us to consider is how early career teachers’ identity and agency may have been shaped to make them stay in, or depart from, teaching. For this purpose, a framework on connecting identity and agency is proposed as an analytic lens, to underpin early career teachers’ decisions to join, stay in, or leave the teaching profession (

).

Proposed framework on agency and identity.

In the proposed framework, identity is an emergent property, arising from the configuration of identity resources and individuals’ agency in responding to structures. Agency may remain unexercised if a relevant identity resource is not experienced by an individual. Agency may hinder, or facilitate, specific aspects of professional identity in an individual’s practices. Professional practices thus emerge at the intersection of identity resources and individual/collective agency. With a focus on early career teachers, Trent [22][23] and Harfitt [24] also highlighted the intricate relationship between agency and identity. Early career teachers enact agency through making choices about what to engage in, and taking actions in shaping their professional identities [25].

To explain how individuals respond to the perceived identities, the researcher draws on Bourdieu’s [26] concept of habitus or socialized norms and structures that guide behaviors and thinking. As illustrated in

, individuals encounter identity resources with dispositions in the forms of beliefs about who they think they are, and who they want to become. These dispositions are the result of individuals’ previous experiences. It is argued that a teacher’s professional identity practices are caused, non-consciously, by his/her habitus if identity is compatible with an individual’s sense of self and his/her ideal self. However, an individual’s responses to incompatible identities happen through reflexive deliberations, which, in turn, are mediated by their identity perceptions. The intricate relationship between agency and identity commitment affects the teachers’ choices and actions in seeking professional development. In particular, it underpins a teacher’s decision to stay in or leave the profession.

References

- Biesta, G.J.J.; Tedder, M. How Is Agency Possible? Towards an Ecological Understanding of Agency-As-Achievement; Working Paper 5; Exeter: Devon, UK, 2006.

- Biesta, G.J.J.; Tedder, M. Agency and learning in the lifecourse: Towards an ecological perspective. Stud. Educ. Adults 2007, 39, 132–149.

- Priestley, M.; Biesta, G.; Robinson, S. Teacher agency: What is it and why does it matter? In Flip the System: Changing Education from the Bottom Up; Kneyber, R., Evers, J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; pp. 134–148.

- Priestley, M.; Edwards, R.; Priestley, A.; Miller, K. Teacher agency in curriculum making: Agents of change and spaces. Curric. Inq. 2012, 42, 191–214.

- Johnson, K.E. The sociocultural turn and its challenges for second language teacher education. TESOL Q. 2006, 40, 235–257.

- Kayi-Aydar, H. Teacher agency, positioning, and English language learners: Voices of pre-service classroom teachers. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2015, 45, 94–103.

- Sloan, K. Teacher identity and agency in school worlds: Beyond the all-good/all-bad discourse on accountability-explicit curriculum policies. Curric. Inq. 2006, 36, 119–152.

- Heikonen, L.; Pietarinen, J.; Pyhältö, K.; Toom, A.; Soini, T. Early career teachers’ sense of professional agency in the classroom: Associations with turnover intentions and perceived inadequacy in teacher–student interaction. Asia Pac. J. Teach. Educ. 2017, 45, 250–266.

- Brubaker, R.; Cooper, F. Beyond ‘‘identity’’. Theory Soc. 2000, 29, 1–47.

- Wenger, E. Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998.

- Garner, J.K.; Kaplan, A. A complex dynamic systems perspective on teacher learning and identity formation: An instrumental case. Teach. Teach. Theory Pract. 2019, 25, 7–33.

- Geijsel, F.; Meijers, F. Identity learning: The core process of educational change. Educ. Stud. 2005, 31, 419–430.

- Vetter, A.; Hartman, S.V.; Reynolds, J.M. Confronting unsuccessful practices: Repositioning teacher identities in English education. Teach. Educ. 2016, 27, 305–326.

- Beijaard, D.; Verloop, N.; Vermunt, J. Teachers’ perceptions of professional identity: An exploratory study from a personal knowledge perspective. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2000, 16, 749–764.

- Trent, J. ‘Four years on, I’m ready to teach’: Teacher education and the construction of teacher identities. Teach. Teach. Theory Pract. 2011, 17, 529–543.

- Morrison, C. Teacher identity in the early career phase: Trajectories that explain and influence development. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 2013, 38, 91–107.

- Beijaard, D.; Meijer, P.C.; Verloop, N. Reconsidering research on teachers’ professional identity. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2004, 20, 107–128.

- Akkerman, S.F.; Meijer, P.C. A dialogical approach to conceptualizing teacher identity. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2011, 27, 308–319.

- Urmston, A.; Pennington, M. The beliefs and practices of novice teachers in Hong Kong: Change and resistance to change in an Asian teaching context. In Novice Language Teachers; Farrell, T., Ed.; Equinox: London, UK, 2008; pp. 89–103.

- Fantilli, R.D.; McDougall, D.E. A study of novice teachers: Challenges and supports in the first years. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2009, 25, 814–825.

- Schaefer, L. Beginning teacher attrition: A question of identity making and identity shifting. Teach. Teach. Theory Pract. 2013, 19, 260–274.

- Trent, J. Discourse, agency, and teacher attrition: Exploring stories to leave by amongst former early career English language teachers in Hong Kong. Res. Pap. Educ. 2017, 32, 84–105.

- Trent, J. Why some graduating teachers choose not to teach: Teacher attrition and the discourse-practice gap in becoming a teacher. Asia Pac. J. Teach. Educ. 2018, 47, 554–570.

- Hong, J.Y. Why do some beginning teachers leave the school, and others stay? Understanding teacher resilience through psychological lenses. Teach. Teach. Theory Pract. 2012, 18, 417–440.

- Billett, S. Work, subjectivity and learning. In Work, Subjectivity and Learning: Understanding Learning through Working Life; Billett, S., Fenwick, T., Somerville, M., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2006; pp. 1–20.

- Bourdieu, P. Outline of a Theory of Practice; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1977.