Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by MARIA Rosa Ciriolo and Version 2 by Peter Tang.

Glutathionylation, that is, the formation of mixed disulfides between protein cysteines and glutathione (GSH) cysteines, is a reversible post-translational modification catalyzed by different cellular oxidoreductases, by which the redox state of the cell modulates protein function.

- glutathione

- glutathionylation

- redox signaling

- infection

- inflammation

1. Introduction

The tripeptide γ-l-glutamyl-l-cysteinyl-glycine, or glutathione (GSH), is the most abundant eukaryotic intracellular thiol, found in a concentration range of 1–10 mM. It is mainly localized in the cytosol (up to 90%), but it is also present in the mitochondria (10%), the endoplasmic reticulum, and the nucleus in a small percentage [1]. The antioxidant activity of GSH is probably the best known and popular function of this molecule; in fact, thanks to the reactivity and the reducing ability of its cysteinyl residue’s sulfhydryl (-SH) group, it can quickly react with and neutralize potentially dangerous molecules, both of endogenous and exogenous origin, as reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS and RNS, respectively), xenobiotics, and metals [2].

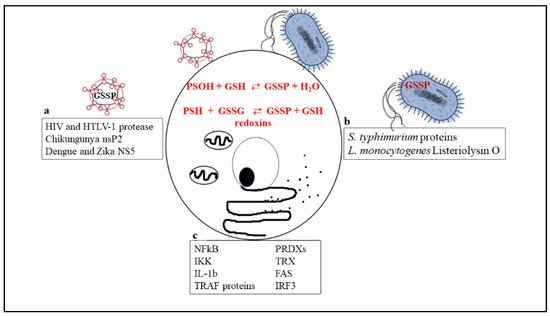

However, today it is well known that the essential role of GSH overcomes its scavenger activity and it plays a crucial role in cell fate, regulating processes such as proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis, and several other cellular functions, ranging from metabolism to immune and inflammatory response [3][4][5][6][3,4,5,6]. In fact, the concentration of GSH and its oxidized form, glutathione disulfide (GSSG), mainly determines the redox state of the cell. Together with other thiol redox couples, such as Trx-SH/Trx-SS, GSH/GSSG acts as a sensor of intracellular redox changes and couples these modifications to redox-dependent biochemical processes [7]. What are the mechanisms by which GSH/GSSG plays a role in signaling? Keeping in mind that the GSH/GSSG couple is the main determinant of H2O2 level, which is a well-known intracellular messenger in signal transduction (see reviews [8][9][10][11][12][13][8,9,10,11,12,13]), it can play a direct role in signaling through glutathionylation, that is, the formation of mixed disulfides between its cysteine and the cysteine of a protein [14]. As for the processes regulated by phosphorylation, the redox-mediated signal impacts proteins through a specific amino acid residue (i.e., cysteine). Several modifications of the thiol group can occur for structural needs, such as inter/intrachain disulfide –SS–, or different degrees of oxidative stress, such as the sulfenic –SOH, sulfinic –SO2H, sulfonic –SO3H, and mixed disulfide with cysteine or glutathione –SSR [15]. A prerequisite for cysteine residue modification is its accessibility by the solvent and a peculiar reactivity imposed by near amino acids. Indeed, the pK value of the cysteine thiol group is around 8.0 and, therefore, always protonated at physiological pH. The so-called “reactive cysteine”, instead, is localized in a basic milieu that stabilizes the thiolated form –S− and represents a very reactive group. The formation of glutathionylated proteins (GSSPs) has been known for many years. Initially considered an effect of oxidative stress and damage [16][17][16,17], it then became clear that it occurred also under physiological conditions and, being a reversible process, could have a role in redox signaling [18][19][20][18,19,20]. GSSPs can be formed by different biochemical reactions: through the formation of sulfenic acids (reaction below (1)) or the thiol–disulfide exchange that occurs between GSSG and protein thiols (2). The reaction can be reversibly catalyzed by different enzymes belonging to the family of thiol–disulfide oxidoreductases or redoxins, including glutaredoxin (Grx) [21], where reversibility and catalysis are important requirements for the regulatory role of the process [22][23][22,23].

(1) PSOH + GSH ⇄ GSSP + H2O

(2) PSH + GSSG ⇄ GSSP + GSH

redoxins

It is known that several proteins undergo glutathionylation, resulting in different biological effects [23][24][23,24]. Most studies on the identification of glutathionylated proteins have focused on cellular proteins, including proteins involved in host response to infections, but there is a growing number of reports showing that microbial proteins also undergo glutathionylation [25].

2. Glutathionylation in Infections

2.1. Viral Infections

It is well known that viruses alter the intracellular redox state to pro-oxidant conditions, which is an alteration that contributes to viral pathogenesis [26][27][28][29][30][31][26,27,28,29,30,31]. Thus, researchers have been evaluating redox signaling as a potential target for antiviral strategies [32][33][34][35][36][37][38][32,33,34,35,36,37,38]. Virus-induced redox imbalance has been measured in terms of ROS overproduction and/or GSH depletion in different viral infections, with different kinetics and mechanisms according to the type of virus and cell host [39][40][41][42][43][44][45][46][39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46]. Based on what has been discussed so far—protein glutathionylation is a physiological process amplified by oxidative stress, and viruses induce a redox imbalance towards a pro-oxidant state—it is not surprising to wonder if glutathionylated proteins are detectable during viral infections and if viral proteins themselves undergo glutathionylation.

2.2. Bacteria

Growing evidence highlights the importance of LMW thiols and GSH in bacteria [25][47][25,68]. GSH is present in Gram-negative and some Gram-positive bacteria (i.e., Listeria monocytogenes and Streptococcus agalactiae), while other Gram-positive bacteria produce LMW thiols, such as bacillithiol (BSH) and mycothiol (MSH), with similar functions. These functions, as in eukaryotic cells, include detoxification of different reactive species to maintain the redox balance of the bacteria cytoplasm. Recently, however, the direct role of GSH in virulence has been described for different bacteria. For example, it has been shown that GSH activates virulence gene expression in the intracellular pathogen L. monocytogenes [48][69]. Similarly, BSH has been shown to be involved in the virulence of some clinical isolates of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus [49][50][70,71], and MSH is essential for the growth and survival of Mycobacterium tuberculosis during infection [51][72].

3. Glutathionylation in Inflammation

The final section of this review is dedicated to a brief analysis of glutathionylation in inflammation, focusing on nuclear factor kappa β transcription factor (NFκB)’s glutathionylation.

NFκB is a transcription factor that plays an important role in the activation of proinflammatory response. Under physiological conditions, NFκB is sequestered in the cytoplasm in a latent form by inhibitor κB (IκB). After phosphorylation by IκB kinase (IKK), IκB undergoes degradation via proteasomes and NFκB is then free to move into the nucleus, where it induces transcription of proinflammatory genes. Various studies have shown that glutathionylation, through the bond of GSH to the DNA binding domain, is able to regulate the activity of many transcription factors, including NFκB [52][53][78,79]. In particular, the p65 subunit of NFκB has been reported to be glutathionylated in different conditions, such as after supplementation of GSH, which leads to DNA binding inhibition [53][79]. It has been also demonstrated that the treatment of endothelial cells with an electrophilic compound (cinnamaldehyde) induced p65-glutathionylation, leading to the inhibition of TNF-α-induced p65 nuclear translocation and ICAM-1 expression [54][80]. During treatment with cinnamaldehyde, the authors also observed an increase of Grx1 protein level. The downregulation of Grx1 abolished p65-glutathionylation and blocked the inhibition of its nuclear translocation and ICAM-1 expression, suggesting that the enzyme is involved in cinnamaldehyde-mediated NFκB inhibition. In a subsequent study, it was shown that treatment with another electrophilic compound, 15-deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J (2) (15d-PGJ (2)), caused p65-glutathionylation, again suppressing p65 nuclear translocation and the expression of ICAM-1, thus working as an anti-inflammatory molecule [55][81]. Treatment of hepatocytes with H2O2 also induced p65-glutathionylation and its retention in the cytoplasm, leading to an increase of the apoptotic rate of hepatocytes [56][82]. Besides p65, S-glutathionylation was also observed for the p50 subunit of NFκB on Cys-62. This post-translational modification reversibly inhibited its DNA binding activity [57][83].

Moreover, IKK, the protein responsible for IκB phosphorylation and NFκB translocation to the nucleus, can be inactivated by S-glutathionylation of Cys-179 [58][84]. So, the NFκB complex, as well as upstream proteins such as TRAF6, is negatively regulated via glutathionylation [59][85]. In these two studies, it was shown that knockdown of Grx1 hampered IKK and TRAF6 deglutathionylation, respectively, and reduced NFκB activation, indicating the importance of Grx1-mediated deglutathionylation in modulating the NFκB signaling pathway [59][85]. Moreover, both p65 and IKKa have been shown to be regulated by the Grx1/glutathionylation axis in IL-17A-stimulated epithelial cells, contributing to IL-17A-induced proinflammatory response [60][86].

Jones et al. [61][87] demonstrated that glutathione S-transferase (GSTP) is another enzyme capable of inducing the S-glutathionylation of many proteins under conditions of oxidative stress. The authors highlighted that, in unstimulated cells, GSTP bound the NFκB inhibitor, IκBα, while exposure to LPS led to their dissociation. LPS treatment also induced GSTP association with IKKβ and IKKβ-S-glutathionylation to increase. The inhibition of GSTP with siRNA, causing a decrease in IKKβ-S-glutathionylation, enhanced NFκB nuclear translocation, its transcriptional activity, and production of proinflammatory cytokines [61][87].

Finally, we have to mention that interleukin-1β, together with a group of cytokines, has been shown to undergo glutathionylation itself [62][88]. In particular, the authors demonstrated that IL-1β glutathionylation at the conserved cysteine Cys-188 protected it from ROS deactivation, making it necessary for maintaining cytokine bioactivity. Grx1 is the physiological negative regulator of the glutathionylation process, and it has been suggested to be a new potential therapeutic target in the treatment of various infectious and inflammatory diseases.

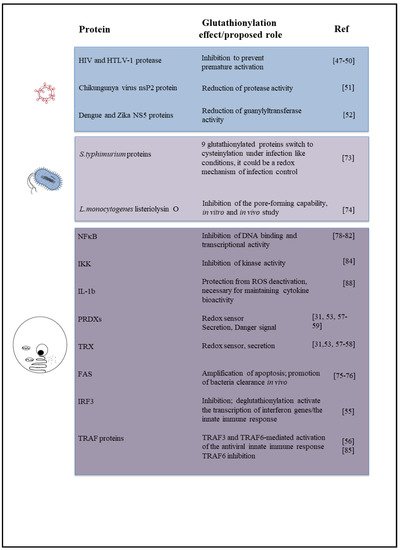

Figure 1 is a schematic picture of the glutathionylated proteins described in this review, and Figure 2 summarizes the effects of glutathionylation on those proteins.

Figure 1. Biochemical reactions through which glutathionylated proteins can be formed and a list of proteins that have been shown to undergo glutathionylation in viruses (a), bacteria (b), or cellular immune/inflammatory pathways (c).

Figure 2. Diagram summarizing the effect or biological role, known or proposed, of glutathionylation on proteins described in this review, including the relevant references.