Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Sebastian Boltana and Version 2 by Rita Xu.

Animals have developed numerous adaptation strategies to survive in changing environmental conditions. This adaptive process allows them to generate physiological and behavioural responses upon exposure to natural factors such as temperature.

- mobile ectotherm

- inflammatory reflex

- cholinergic neuron

1. Background

Animals have developed numerous adaptation strategies to survive in changing environmental conditions. This adaptive process allows them to generate physiological and behavioural responses upon exposure to natural factors such as temperature. Unlike endotherms, ectotherm organisms adjust their cellular and molecular metabolism to counteract temperature constraints [1][2][1,2]. This thermal-induced response developmental program requires the function of interconnected organismal systems and signalling. However, the nature of this response and how it is molecularly activated are not well understood in most of the organisms studied.

Under pathogen invasion and organ damage, the coordinated and bidirectional interaction between the nervous and immune system is regulated by the so-called inflammatory reflex [3][4][5][3,4,5]. During this response, immune molecules activate the afferent and efferent sensory neural arc to modulate a fine crosstalk between these systems [5][6][5,6], even under temperature changes [7][8][7,8]. Therefore, understanding the molecular program facilitating its activation is relevant to reveal thermoregulatory pathways functioning in fever.

In mammals, the inflammatory reflex is mediated by muscarinic receptors and cholinergic activity (reviewed in [5][9][5,9]), specifically, it is exerted through the function of the cholinergic receptor nicotinic alpha 7 subunit (Chrna7) and beta-2 adrenergic receptor (Adrb2) [10][11][12][10,11,12]. Additionally, the cholinergic pathway confers protection in peripheral organs, inflammatory conditions, and fever [13][14][13,14]. For instance, it suppresses excessive inflammation in the liver [15], heart [16], pancreas [17], and gastrointestinal tract [18]. In rats, mecamylamine-mediated blocking of the Chrna7 activity enhances inflammation severity [17]. In mice, the local administration of the agonist acetylcholine (ACh) into the spleen activates Chrna7. As a result of such activity, pro-inflammatory cytokines expression is inhibited, including tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNFα), interleukin-1 beta (Il1β), and interleukin-6 (Il6). Additionally, it affects the expression of releasing anti-inflammatory mediators such as interleukin-10 (Il10) and transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) [5]. Recent findings have also shown that, in diabetic mice, selective ablation of the Chrna7 promotes a low inflammatory activity mediated by peritoneal macrophages [19]. Altogether, these findings suggest conserved functions for cholinergic neurons in the immune response regulation. However, the functional relevance of Chrna7 during inflammation in lower vertebrates remains unexplored.

Additionally, equivalent molecule functions have been identified in ectothermic vertebrates, including fish. For example, nicotinic acetylcholine receptor transcripts have been detected in teleosts, including the zebrafish (Danio rerio) [20] and fugu (Takifugu rubripes) [21]. In rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss), Drescher and colleagues cloned the ACh receptor from saccular hair cells [22]. In zebrafish, two paralogs of the chrna7 gene have been identified. In addition, a 1716 base pair (bp) in length transcript encoding a 509 amino acids protein is strongly expressed in different organs such as the brain, stomach, heart, muscle, and gonads [20]. Chrna7 also expresses in rainbow trout macrophages [23] and plays a role during viral infection in the zebrafish [2]. Other inflammatory reflex components, including acetylcholinesterase (AChE), have been detected in mononuclear cells from tilapia [24]. This enzyme catalyses the breakdown of ACh and of some other choline esters that function as neurotransmitters [25]. However, how cholinergic components function in the inflammatory reflex in teleost fish is still uncertain.

Unlike mammals, ectotherm organisms lack natural thermogenesis and therefore elevate their body temperature by moving to a warmer place [2][7][2,7]. Behavioural fever promotes organismal survival by enhancing protective mechanisms [26][27][28][29][30][31][32][26,27,28,29,30,31,32], including fever in endotherms [9]. In ectotherms, however, the underlying regulatory mechanisms triggered during behavioural fever are not well understood to date. Cumulative findings show that increased temperature during behavioural fever correlates with an acute immune response [2][7][8][2,7,8]. How thermal coupling influences the neural–immune system interaction and the cholinergic pathway activation during inflammation remains unclear in mobile ectotherms.

2. Viral Infection Influences a Behavioural Fever Mechanism in Mobile Ectotherms

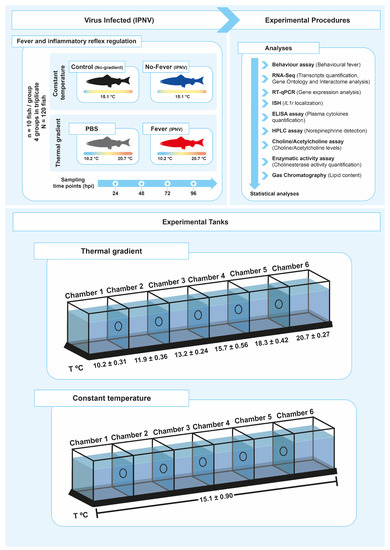

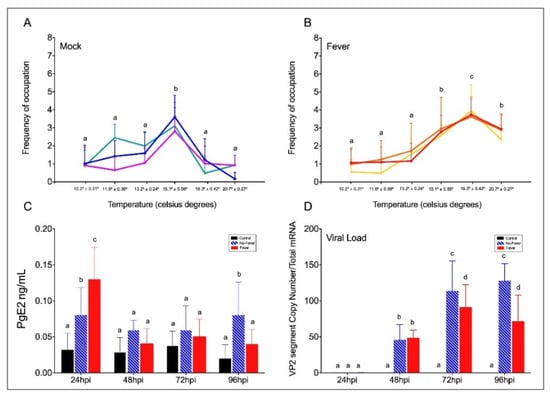

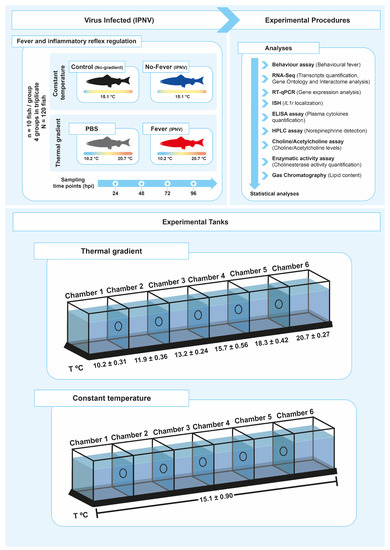

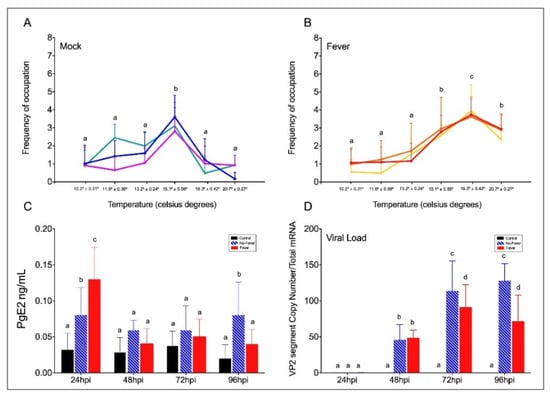

Behavioural fever manifests in response to pathogen challenge, including viral infection. To address whether aspects of behavioural fever are activated in fish as an immune response, we exposed salmon parr to an IPNV challenge under thermal treatment. All fish were infected at 12 °C for 96 h (enough time for the virus to initiate the infection) (Figure 1). Uninfected fish that were kept in a range of 10–20 °C in multi-chamber tanks showed that most of them preferentially distributed in the compartments ranged between 13 and 15 °C (chambers 3 and 4) (Figure 2A and Supplementary Figures S1A and S2A). The virus-infected individuals shifted their thermal preference and moved to warmer temperatures ranging between 18 and 20 ºC (chambers 5 and 6) over a 96 h period (Figure 2B and Supplementary Figures S1B and S2B). Statistical data analysis from three replicates showed that virally infected individuals manifested behavioural fever, as revealed by a significantly higher number of fish moving toward 18.3 ± 0.42 °C (chamber 5, Figure 2A,B; Wald test p < 0.001). The behavioural analysis performed (Wald’s test) differentiates preferential occupation for each chamber between the experimental groups. The analysis showed that individuals with access to temperature (fever group) spent significantly more time in chamber 5 (18.3 °C), unlike what was observed in mock-infected individuals. Phenotypic analysis performed on infected fish showed no physical abnormalities. This result validates, under viral infection, the development of a robust and specific behavioural fever response in fish.

Figure 1. Experimental setup. Schematic representing the experimental design of thermal treatments after viral challenge. A summary of all analyses performed to study the neuro-immune interaction in the control of inflammation during behaviour fever in fish is presented (A). The experimental tanks set-up and the temperature associated with each chamber are also shown (B). The mean temperature ± SD value for each chamber is indicated. IPNV: infectious pancreatic necrosis virus; hpi: hours post-infection; SD: standard deviation.

Figure 2. Behavioural fever in IPNV-challenged Salmon salar. (A) Frequency of chamber occupation in non-challenged individual fish (mock individuals = non-infected group in thermal gradient tank) over the 96 hpi period. The blue, green, and purple lines represent the frequency of occupation in each chamber by each technical replicate; mock (n = 3 technical replicates, mean ± SD). (B) Frequency of chamber occupation of IPNV-challenged individual fish. The red, yellow, and orange lines represent the frequency of occupation in each chamber by each technical replicate of fish challenged with IPNV under thermal gradient tank (n = 3 technical replicates, mean ± SD). (C) Plasma concentration of PgE2 (ng ml−1) in IPNV-infected fish. Bar graph showing differences between control (uninfected fish, black bars), no-fever (dashed blue bars), and fever (red bars) individuals (mean ± SD, two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test, p < 0.0001). Different letters denote significant differences. (D) Viral load expressed as the abundance of VP2 segment (targeted with primer WB117) of the IPNV detected by RT-qPCR in the spleen. Bar graphs showing the differences between control (uninfected fish, black bars), no-fever (dashed blue bars), and fever (red bars) individuals (mean ± SD, two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test, p < 0.001). Different letters denote significant differences. The mean and SD value for the copy number of the VP2 segment transcript per ng of total RNA is shown. IPNV: infectious pancreatic necrosis virus; hpi: hours post-infection; SD: standard deviation.

In fish, behavioural fever is driven by peripheral inflammatory cytokines and PgE2 synthesis in response to pathogens [8]. We next examined the levels of PgE2 in control and viral-challenged salmon with access to the thermal gradient. We found that at 24 hpi, PgE2 synthesis was significantly higher in virus-infected individuals with access to the thermal gradient than in those infected but under limited thermal choice (Figure 2C). Then, it decreased in both treatments. This concentration pattern has previously been observed, and PgE2 was suggested to be a key precursor of behavioural fever in fish [2][8][2,8]. To investigate the temperature-dependent effect of behavioural fever on viral replication, we evaluated IPNV load over time in infected individuals. Quantitative analysis of the VP2 segment mRNA, as a readout of viral load (Figure 2D), revealed that fever significantly decreased systemic replication of the virus (significant at 72 and 96 hpi; two-way ANOVA p < 0.001). These data show a strong association between infection and temperature choice and reveal a behavioural fever mechanism driving viral clearance in ectotherms.

3. An Inflammation Activation Threshold Is Modulated by Behavioural Fever

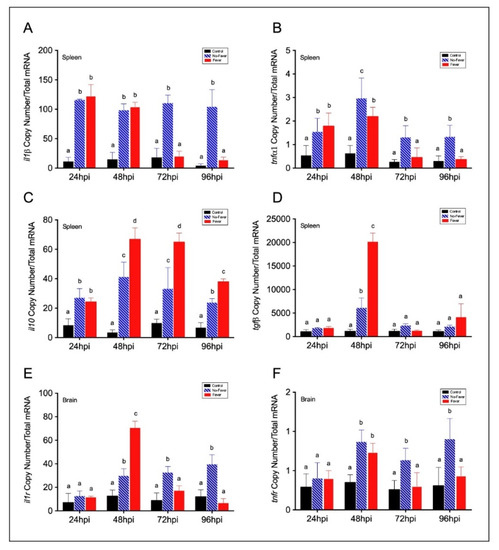

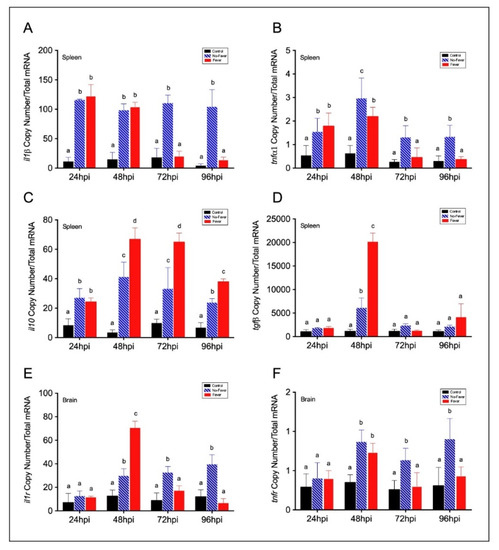

Although the mechanistic basis for behavioural fever has been previously described in ectotherms [8], these fail to explain how temperature changes regulate inflammation over an extended time. Thus, once we identified a potential thermoregulatory mechanism mediating the response-specific inflammatory factors expression under the viral infection, we investigated the contribution of fever in this process. To address this hypothesis, we adapted the IPNV immersion challenge to salmonid fish under the thermal regimes described above for 5 days post-viral infection. We characterized in detail markers of the inflammatory response in the whole brain, spleen, and plasma of infected individuals sampled each 24 hpi. By performing RT-qPCR and ELISA assays, we analysed pro-inflammatory cytokine profiles. After infection, the mRNA abundance of pro-inflammatory cytokines il1β (Figure 3A) and tnfα1 (Figure 3B) showed a significant difference between no-fever and fever individuals at 72 and 96 hpi (p-value p < 0.001; two-way ANOVA). Specifically, there were no significant differences in the il1β copy numbers between no-fever and fever groups at 24–48 hpi. After 48 hpi, il1β mRNA abundance significantly decreased in the behavioural fever group (Figure 3A). Alternatively, tnfα1 transcript increased up to reaching a significant peak at 48 hpi in the no-fever individuals. However, after this time point onward it dramatically decreased in the fever group, and no significant differences were found between these groups prior to this time point (Figure 3B). The il1β and tnfα1 cytokines mRNAs expression patterns were detected only in individuals that developed behavioural fever, in stark contrast to what was found in the no-fever group. This group showed a post-infection inflammatory response that was maintained through time. The observed differences can be due to the effect of temperature on the kinetics of the reactions; however, functional studies must elucidate the molecular bases of this regulatory mechanism.

Figure 3. Expression profiles among pro- and anti-inflammatory factors in IPNV-infected fish spleen and brain. (A–D) Bar graph showing differences of inflammatory mRNAs abundance between control and IPNV-infected individuals under the thermal treatments. Expression of spleen pro-inflammatory il1β (A) and tnfα1 (B) and anti-inflammatory il10 (C) and tgfβ (D) transcripts in IPNV-challenged fish is shown. (E,F) Transcript expression profiles of neural inflammatory cytokines receptors il1r (E) and tnfr (G). Bar graphs showing the differences between control (uninfected individuals, black bars), no-fever (dashed blue bars), and fever (red bars) individuals (mean ± SD, two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test, p < 0.01). Different letters denote significant differences. The mean and SD value for the copy number of inflammatory mediators and receptors mRNAs per ng of total RNA is shown. IPNV: infectious pancreatic necrosis virus; hpi: hours post-infection; SD: standard deviation.