Rural clean heating project (RCHP) in China aims to increase flexibility in the rural energy system, enhance the integration of renewable energy and distributed generation, and reduce environmental impact.

- rural clean heating project

- rural Gansu

- sustainability

- potential solutions

- benchmarking

1. Building Conservation-Minded Society

After the first two-decade development in the 21st century, many countries in the world regard “harmonious development between human and nature” as the key of state construction in the next stage, especially after the COVID-19 disaster [1][2][3][4][5]. Particularly, the developed countries in Europe put “renewable energy evolution based new-age industrial revolution” into their national development programs [6][7][8][9][10].

In China, people are confronted with three challenges and/or opportunities: the scientific and technological revolution, the energy revolution, and the ecological revolution. Based on the “development-improvement” experience by western world, Chinese people adopt a sustainable development strategy in building a conservation-minded society (CMS) [11][12][13][14][15].

Energy saving is an important part of CMS, and building energy saving (BES) is the substantial portion [16][17][18]. Therefore, BES as a national strategic support is in line with the scientific development law.

Through long-term, active, and extensive participation of the whole society, China has made an extraordinary progress in three major sectors of urban residential energy saving, public building energy saving, and central heating system energy saving in the north. However, rural China, being the key rear area supporting China’s reform and opening-up, faces many challenges from the clean heating project [17][18].

2. Rural Clean Heating Project

Since 2005, the characteristics of rural housing energy consumption and its composition have undergone profound changes with the promotion of New Rural Construction (NRC (The detailed information about NRC can be taken onhttp://qgxnc.org/, accessed on 3 February 2021)) and the improvement in peasant farmer’s living standards. The most conspicuous variation is rural energy-use structure. Over the past 20 years, the consumption of commodity energy in rural China has been increasing year by year. Meanwhile the consumption of non-commodity energy (biomass energy, especially) has been decreasing [17][18].Furthermore, the total energy consumption in rural areas continues to rise, although the resident population (composed mainly of old people, young children, and school-age children (More information on rural China can be gotten on

, accessed on 3 February 2021)) and the improvement in peasant farmer’s living standards. The most conspicuous variation is rural energy-use structure. Over the past 20 years, the consumption of commodity energy in rural China has been increasing year by year. Meanwhile the consumption of non-commodity energy (biomass energy, especially) has been decreasing [17,18].Furthermore, the total energy consumption in rural areas continues to rise, although the resident population (composed mainly of old people, young children, and school-age children (More information on rural China can be gotten on , accessed on 3 February 2021)) in rural China continues to decline in the meantime, which means that the rural energy-use intensity tends to grow all the time. On the one hand, increased rural energy demand may indicate the improvement in peasant farmer’s living conditions. On the other hand, the lower proportion of renewable energy in rural energy consumption is very worrying, since it works against the low-carbon development path advocated by the government. Therefore, the key to transform energy use in rural China lies in structural optimization of energy use and increase in renewable proportion [18].Field research shows that the crucial domestic terminals of rural energy use consist of heating, cooking (including domestic hot water), and electricity consumption for household electric appliances and lighting. Among them, wastage from heating accounts for 53.6% and even more than 60% of waste in some areas in rural China [17][18]. Thus, the rural clean heating project (RCHP) is of great significance to the evolution of CMS in China.

Field research shows that the crucial domestic terminals of rural energy use consist of heating, cooking (including domestic hot water), and electricity consumption for household electric appliances and lighting. Among them, wastage from heating accounts for 53.6% and even more than 60% of waste in some areas in rural China [17,18]. Thus, the rural clean heating project (RCHP) is of great significance to the evolution of CMS in China.3. Progress of RCHP in Rural Gansu

3.1. Current State of Rural Gansu

http://www.gansu.gov.cn/col/col10/index.html

Figure 1

http://www.gansu.gov.cn/col/col10/index.html

2

Figure 1.

http://www.gansu.gov.cn/col/col10/index.html

http://www.gov.cn/shuju/chaxun/index.htm

3.2. Living Energy-Use Reality in Rural Gansu

Table 1 details the annual consumptions of diverse energy resources in rural Gansu [17][18].

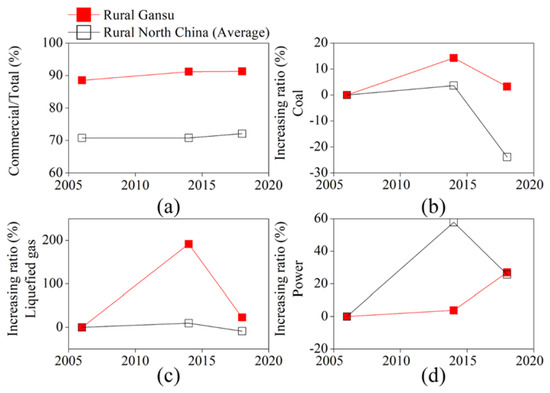

Figure 2 depicts the commercial energy consumption in a comparison with the north average [17][18]. It can be found in

Table 1

Figure 2.

a

b

c

d) the increasing ratio of power consumption; Note: The complete data can be found in References [17][18].

Table 1.

| Year | Name | Unit | Value | Average | Deviation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 | Total building area | 10 | 8 | m | 2 | 3.4 | 5.3 | −35.8% |

| Coal | 10 | 4 | t | 779 | 1018.9 | −23.5% | ||

| Liquefied gas | 10 | 4 | t | 1.2 | 13.5 | −91.1% | ||

| Power | 10 | 8 | kWh | 15.7 | 29.4 | −46.6% | ||

| Firewood | 10 | 4 | t | 55 | 287.6 | −80.9% | ||

| Crop straw | 10 | 4 | t | 92 | 357.1 | −74.2% | ||

| Commercial energy | 10 | 4 | tec | 610 | 849.4 | −28.2% | ||

| Non−Com. energy | 10 | 4 | tec | 79 | 348.4 | −77.3% | ||

| Sum | 10 | 4 | tec | 689 | 1200.5 | −42.6% | ||

| 2014 | Total building area | 10 | 8 | m | 2 | 3.7 | 5.9 | −37.3% |

| Coal | 10 | 4 | t | 890 | 1056.1 | −15.7% | ||

| Liquefied gas | 10 | 4 | t | 3.5 | 14.8 | −76.4% | ||

| Power | 10 | 8 | kWh | 16.3 | 46.4 | −64.9% | ||

| Firewood | 10 | 4 | t | 45 | 329.7 | −86.4% | ||

| Crop straw | 10 | 4 | t | 80 | 352.9 | −77.3% | ||

| Commercial energy | 10 | 4 | tec | 695 | 928.1 | −25.1% | ||

| Non−Com. energy | 10 | 4 | tec | 67 | 383.1 | −82.5% | ||

| Sum | 10 | 4 | tec | 762 | 1311.1 | −41.9% | ||

| 2018 | Total building area | 10 | 8 | m | 2 | 3.4 | 5.3 | −35.8% |

| Coal | 10 | 4 | t | 918.8 | 803.6 | 14.3% | ||

| Liquefied gas | 10 | 4 | t | 4.3 | 13.5 | −68.1% | ||

| Power | 10 | 8 | kWh | 20.7 | 58.3 | −64.5% | ||

| Firewood | 10 | 4 | t | 46.5 | 265.5 | −82.5% | ||

| Crop straw | 10 | 4 | t | 82.6 | 315.5 | −73.8% | ||

| Commercial energy | 10 | 4 | tec | 723.6 | 818.5 | −11.6% | ||

| Non−Com. energy | 10 | 4 | tec | 69 | 317.1 | −78.2% | ||

| Sum | 10 | 4 | tec | 792.6 | 1135.5 | −30.2% |

Note: the commercial energy mentioned in this table includes coal, liquefied gas, and power electricity; the non-commercial energy (Non-Com.) includes firewood and crop straw. The source of data in Table 1 is Reference [17], National Bureau of Statistics of China. China Statistical Yearbook. http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/ndsj/; accessed on 3 February 2021.

Figure 2

Figure 2

Figure 2

Based on the other studies we can understand that there is a significant gap between energy-use demand and energy supply in rural Gansu, and there is a great divergence between its energy structure and the sustainability goals of China [11][12][13][14][15][16]. Furthermore, the contradictions existing in the peasant farmers’ living conditions and their health targets are obvious [18]. In particular, the indoor air temperatures in rural Gansu are generally low with cold air infiltration, and the indoor air quality is poor caused by coal combustion [18].