Skeletal muscle atrophy is the decrease in muscle mass and strength caused by reduced protein synthesis/accelerated protein degradation. Various conditions, such as denervation, disuse, ageing, chronic diseases, heart disease, obstructive lung disease, diabetes, renal failure, AIDS, sepsis, cancer, and steroidal medications, can cause muscle atrophy. Mechanistically, inflammation, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial dysfunction are among the major contributors to muscle atrophy, by modulating signalling pathways that regulate muscle homeostasis. To prevent muscle catabolism and enhance muscle anabolism, several natural and synthetic compounds have been investigated. Recently, polyphenols (i.e., natural phytochemicals) have received extensive attention regarding their effect on muscle atrophy because of their potent antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. Numerous in vitro and in vivo studies have reported polyphenols as strongly effective bioactive molecules that attenuate muscle atrophy and enhance muscle health.

1. Introduction

The skeletal muscle is a plastic organ and the most abundant tissue in vertebrates. It plays a significant role in metabolism, movement, respiration, protection, daily physical activities, and the maintenance of posture and balance

[1]. Generally, a healthy skeletal muscle always maintains a good equilibrium between protein synthesis and protein degradation. Any physiological (aging) or pathological conditions that interfere with the catabolic and anabolic symmetry of proteins will lead to a reduced cross-sectional area (CSA) of muscle fibers and decreased muscle strength and mass, resulting in muscle atrophy. The three main conditions that trigger muscle atrophy are (I) disuse, including immobilization, denervation, bed rest, space flight, and aging; (II) chronic disease, including chronic heart failure, obstructive lung disease, diabetes, renal failure, AIDS, sepsis, and cancer; and (III) medications, such as glucocorticoids

[2][3][2,3]. Atrophy of the muscle reduces the quality of life and movement independence of the patients, thus imposing an additional financial burden on the health care system and causing increased morbidity and mortality. Hence, maintaining healthy muscles is necessary for preventing metabolic diseases and achieve healthy aging.

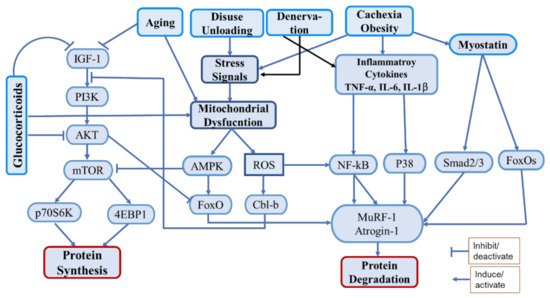

Muscle mass is maintained via the regulation of various anabolic pathways. Among them, the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway is the most important, in which insulin/IGF-1 acts as the upstream molecule to promote protein synthesis and block protein degradation

[4]. The activation of Akt, a serine/threonine kinase, through phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) activates the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) to induce protein synthesis by activating its downstream effectors, the ribosomal protein S6 kinase beta-1 (S6K1), and the eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E (eIF4E)-binding protein 1 (4E-BP1)

[4]. Activated Akt also phosphorylates the Forkhead box O (FoxO) transcription factors, leading to their expulsion from the nucleus, thereby preventing the transcription of genes encoding vital E3 ubiquitin ligases, such as muscle atrophy F-Box (MAFbx/atrogin-1) and muscle RING finger-1 (MuRF-1), or autophagy-related genes, such as those encoding the microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3 (LC3) and Bcl2/adenovirus E1B 19-kDa-interacting protein 3 (Bnip3), which are responsible for protein breakdown mediated by the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) and autophagic–lysosomal pathway, respectively

[4][5][6][4,5,6]. Various proatrophic factors, such as inflammatory cytokines (tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and IL-1β), glucocorticoids, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial damage, were found to reduce Akt activation and induce muscle atrophy

[7][8][9][7,8,9]. Among the protein catabolic pathways, the UPS is the chief proteolytic system, which degrades muscle proteins by upregulating the ubiquitin ligases atrogin-1, MuRF-1, and casitase-B-lineage lymphoma (Cbl-b). Generally, the UPS is activated by impaired PI3K/Akt signaling, inflammatory cytokines, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial dysfunction

[9][10][11][9,10,11]. Furthermore, the nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) transcription factor, which is an inducer of atrogin-1 and MuRF-1, is activated by inflammation and oxidative stress and initiates protein degradation via direct binding to the

MuRF-1 promoter

[12]. Additionally, myostatin, a potent negative regulator of muscle growth and differentiation, induces muscle atrophy by inducing the expression of atrogin-1 and MuRF-1

[13].

Oxidative stress and inflammation are important factors strongly associated with muscle atrophy

[14]. Oxidative stress can be defined as an imbalance between oxidants (ROS) and antioxidants in the body. Several conditions such as chronic diseases, cachexia, disuse, denervation, aging, etc. are associated with increased oxidative stress, that causes activation of proteolytic pathways as well as mitochondrial dysfunction

[15]. The catabolic regulatory elements such as NF-kB, FoxOs, AMPK, etc. are activated by oxidative stress that induce muscle protein catabolism by regulating UPS. It also induces the ubiquitin ligase Cbl-b, which disturbs IGF-1 signaling by ubiquitinating the insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1), which leads to the activation of FoxOs and FoxOs-mediated ubiquitin ligases

[16][17][16,17]. Inflammation triggers muscle atrophy during cachexia, chronic disease, aging, denervation, and obesity. Inflammatory cytokines (TNF-a, IL-6, IL-1b) are released during the above conditions, that interfere with the pathways associated with protein synthesis and proteolysis

[18]. They activate various pathways including NF-kB and p38-MAPK as well as myostatin to induce proteolysis via UPS

[19] (

Figure 1).

Figure 1. Schematic diagram of the main pathways associated with protein synthesis and degradation under various proatrophic conditions.

Muscle atrophy is closely associated with mitochondrial quality. Mitochondrial quality and biogenesis are indispensable factors for proper muscle function, as impaired mitochondrial activities lead to muscle atrophy via the activation of various catabolic pathways

[9][20][9,20]. Healthy mitochondria always maintain muscle homeostasis by producing adequate adenosine triphosphate (ATP) via the tricarboxylic acid cycle and oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS)

[21]. They also regulate the antioxidant defense system and apoptosis (a type of programmed cell death). Moreover, the biogenesis of mitochondria is regulated by the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator 1-alpha (PGC-1α), which activates nuclear respiration factors (Nrf1 and Nrf2) and the estrogen-related receptor-α, which further activates the mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM) to promote mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) replication

[21].

Furthermore, myogenesis plays a vital role in the preservation of muscle health and the attenuation of atrophy. Myogenesis is a process via which satellite cells are differentiated to myofibers to maintain muscle tissue regeneration. This process is regulated by various myogenic regulatory factors, namely, the myoblast determination protein (MyoD), myogenic factor 5 (Myf5), myogenin, and myogenic regulatory factor4, which lead to the determination and differentiation of skeletal muscle cells

[22]. Hence, both healthy mitochondria and myogenesis are required for healthy muscle activities.

Polyphenols (PPs) are naturally occurring organic compounds that are abundantly found in different plants, fruits, vegetables, nuts, seeds, flowers, tea, and beverages

[23]. PPs are worthier because of their diversity, bioactivity, easy accessibility, and specificity of the response, with lower toxicity effects. However, rapid metabolism and low bioavailability are their major drawbacks

[24]. PPs are classified mainly into four groups, i.e., (a) phenolic acids, (b) flavonoids, (c) stilbenes, and (d) lignans, depending on the number of phenol rings included in their structure and the structural components that bind these rings together

[25]. Researchers have reported the wide-ranging health benefits of PPs, including the neuroprotective, cardioprotective, renoprotective, hepatoprotective, antidiabetic, anticancer, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antimicrobial activities of PPs, which can be attributed to their diverse biological properties

[24]. Thus, recently, PPs have drawn extensive attention among nutrition scientists regarding the exploration of their improved consumption as functional foods that counteract different diseases. Many of them have been trialed for their possible use as clinical treatments

[26]. PPs have also been reported to exert strong antiatrophic effects by modulating the proatrophic factors or signaling pathways that contribute to muscle atrophy

[27]. Because of their lower toxicity and higher target-specific response, PPs are being vigorously investigated as muscle atrophy countermeasures.

2. Polyphenols in Managing Muscle Atrophy and Muscle Health

2.1. Phenolic Acids

Phenolic acids are important bioactive compounds of the polyphenolic group. They consist of an aromatic ring with several hydroxyl groups attached to it. They are primarily subclassified into two classes: hydroxybenzoic acids and hydroxycinnamic acids. Generally, hydroxybenzoic acid and hydroxycinnamic acid contain seven (C6-C1) and nine (C6-C3) carbon atoms, respectively, in their structure, with few exceptions. For example, compounds such as Ellagic acid of the hydroxybenzoic acid group contain 14 carbon atoms in their structure. Similarly, Chlorogenic acid of the hydroxycinnamic acid group has 16 carbon atoms in its structure. Most commonly they are distributed in cereals: fruits, such as pomegranates, apples, grapes, raspberries, strawberries, cranberries, blackcurrants, and walnuts, and vegetables

[28]. Pharmacologically, they exhibit antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, neuroprotective, cardioprotective, hepatoprotective, antidiabetic, anticancer, and antimicrobial effects

[28]. Some representative phenolic acids have been reported to exert beneficial effects on muscles by promoting their growth and/or reducing their wasting while improving mitochondrial quality and preventing inflammation and oxidative stress, as summarized in

Table 1.

Table 1. Function of phenolic acids and their derivatives in promotion of muscle health and prevention of muscle atrophy. DMD, Duchenne muscle dystrophy; EC, epicatechin; EGC, epigallocatechin; GA, gallic acid; HF: high-fat diet.

| Class |

Sub-Class |

Compound/Derivatives/Compounds Mixture |

Model |

Effects |

References |

| Phenolic Acid |

Hydroxybenzoic Acid |

Gallic Acid (GA) |

C2C12 Myotubes |

Increased Mitochondrial Function and mitochondrial biogenesis,

Enhanced myosin heavy chain expression |

[29] |

| EC, EGC and GA |

Normal and oxidative stress-induced C2C12 cells |

Increased myotube density

upregulated genetic expression of myogenic factors |

[30] |

| Ellagic acid |

CCL4-induced muscle injury in rats |

Reduced muscle tissue damage

induced caspase-3, Nrf-2 and antioxidant enzymes

suppressed inflammatory markers |

[31][32] |

| Ellagic Acid |

Cuprizone-induced multiple sclerosis model in mice |

Protects muscle tissue

prevented mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress |

[32][33] |

| Urolithin A |

C2C12 cells, young and HF-induced aged mice |

Induced autophagy and mitophagy both invitro and in vivo

increased muscle function

improved exercise capacity |

[33][34] |

| Urolithin A |

Mouse model of DMD |

Induced mitophagy and improved muscle function and MuSCs regeneration

increased skeletal muscle respiratory capacity |

[ |

[43][44]. Moreover, the consumption of coffee, a good source of caffeic acid, has been reported to increase skeletal muscle function and hypertrophy by increasing MyHC, MyHC-IIa, and MyHC-IIb in the quadriceps muscle. It suppressed transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) and myostatin expression and upregulated the levels of the insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), and subsequently phosphorylated Akt and mTOR. It also enhanced PGC-1α expression, which is vital for myogenic differentiation. Hence, coffee exerted a protective effect by regulating the TGF-β/myostatin–Akt–mTORC1 pathway

[44][45]. However, P-coumaric acid, of the phenolic acid group, reduced the differentiation of skeletal muscle cells by downregulating myogenin and MyoD

[45][46].

2.2. Flavonoids

Flavonoids are bioactive polyphenolic compounds that are found in almost all fruits and vegetables. They are the most studied natural compounds for their valuable pharmacological effects in different diseases. Approximately 6000 flavonoid compounds are estimated to be distributed in different fruits, vegetables, herbs, and plants

[47]. Flavonoids offer diverse health benefits against chronic diseases, including cardiovascular disease, kidney disease, cancer, diabetes, obesity, and hepatic disease, which lead to increased mortality and morbidity

[48][49][50][48,49,50]. Because of their potent antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities, they can modify various enzymes and signaling molecules that are responsible for disease prognosis

[51]. Numerous in vitro and in vivo studies have reported flavonoids as potential therapeutic countermeasures for treating muscle atrophy or muscle injury via different mechanisms. The effects of each subclass of flavonoid, i.e., flavanols, flavanones, flavones, isoflavones, flavonols, and anthocyanin, have been summarized in

Table 2 and are discussed below.

Table 2. Function of flavonoids and its derivatives in promotion of muscle health and prevention of muscle atrophy. 8-PN, 8-prenylnaringenin; Dex, dexamethasone; EGCG, epigallocatechin gallate.

| Class |

Sub-Class |

Compound/Derivatives |

Model |

Effects |

References |

| Flavonoids |

Flavanols |

EC |

Young and old C57BL/6 mice and human tissue samples |

Decreased myostatin and β-galactosidase

Increased follistatin and markers of muscle growth and differentiation |

[52] |

| EC |

Young and old C57BL/6 mice |

Increased survival of aged mice

prevented muscle wasting |

[53] |

| EC |

HLS-induced muscle atrophy in mice |

Counteracts muscle degradation

maintains muscle angiogenesis and mitochondrial biogenesis |

[54] |

| EC |

Denervation-induced muscle atrophy in rats |

Reduced muscle wasting

down regulated Foxo1a, Atrgoin-1 and MuRF-1 |

[55] |

| EC |

Ambulatory adults with Becker Muscular Dystrophy |

Induced mitochondrial biogenesis and muscle regeneration factors

increased follistatin

decreased myostatin |

[56] |

| 34 | ] | [ | 35] |

| EC |

C2C12 myotubes |

Stimulates mitochondrial biogenesis and cell growth through GPER |

[57] |

Urolithin A |

C57BL/6 mice |

Strengthen skeletal muscle and angiogenesis

Increase ATP and NAD+ level

Upregulates angiogenic pathways |

| EC | [ | 35 | ][36] |

| C2C12 cells |

Enhanced myogenic differentiation and MyoD activity |

[ | 58] |

Urolithin B |

C2C12 myotubes and denervation-induced mice |

Enhanced growth and differentiation of C2C12 myotubes and muscle hypertrophy

Increased protein synthesis and suppressed UPS |

[36][37] |

| EC |

HF-induced muscle damage in aged mice |

Improved physical performance

increased follistatin and MEF2A

decreased Foxo1a and MuRF-1 |

[59] |

Pomegranate extract |

TNF-α induced muscle atrophy in mice |

| EC, ECG, EGCG |

3D-clinorotation induced C2C12 atrophy | Prevented muscle wasting

suppressed cytokines and NF-kB level

activated protein synthesis pathway |

Suppressed Atrogin-1 and MuRF-1

dephosphorylated the ERK signaling[37][38] |

| [ | 60 | ] |

Hydroxycinnamic Acid |

Ferulic acid |

Mouse C2C12 myotubes |

Regulates muscle fiber type formation

activated SIRT1/AMPK pathway

Increased PGC-1α expression |

[ |

| EGCG | 38 | ] |

Aging-induced sarcopenic rat model | [39] |

| Attenuated muscle atrophy and protein degradation |

| Increased protein synthesis |

[61] |

Ferulic Acid |

Corticosteroid-Induced Rat Myopathy |

Induced growth of fast glycolytic and slow oxidative muscle fiber

suppressed myostatin and oxidative stress |

[39][40] |

| Ferulic Acid |

Zebrafish model |

Enhanced muscle mass and MyHC fast type

Increased myogenic transcriptional factors

activated zTOR/p70S6K/4EBP1 |

[40][41] |

| Chlorogenic acid |

Resistance training-induced rat model |

improved muscle strength by promoting mitochondrial function and cellular energy metabolism |

[41][42] |

| Caffeic acid phenethyl ester |

Eccentric exercise-induced skeletal muscle injury in rats |

Protected skeletal muscle damage

down-regulated NF-κB activation |

[42][43] |

| Caffeic acid |

Human fibroblast cell line |

Decreased spinal muscular atrophy

increased SMN2 transcripts |

[43][44] |

| Coffee |

In-vitro and in-vivo model |

Skeletal muscle hypertrophy and myoblast differentiation |

[44][45] |

| P-Coumaric acid |

C2C12 myotubes |

Reduce differentiation of muscle cells by reducing MyoD and Myogenin. |

[45][46] |

Hydroxybenzoic acids include gallic acid, vanillic acid, ellagic acid, salicylic acid, and protocatechuic acid. Few studies have reported the effects of these compounds in skeletal muscle. Recently, Chang et al. (2021) reported that gallic acid improved mitochondrial functions in C2C12 myotubes by activating SIRT-1, which in turn activates the transcription factors PGC-1α, Nrf1, and TFAM, to promote mitochondrial biogenesis. It also upregulated mitochondrial biogenesis, oxidative phosphorylation, myosin heavy chain (MyHC) content, autophagy/mitophagy, and the fusion/fission index of mitochondria in C2C12 myotubes

[29]. Gallic acid (GA) in combination with epicatechin (EC) and epigallocatechin (EGC) increased muscle differentiation by inducing the myogenic regulatory factors myogenin, Myf5, and MyoD in C2C12 myotubes

[30]. Another compound of this class, ellagic acid, exerts antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anticancer, hypolipidemic, and neuroprotective effects

[46][31]. Ellagic acid treatment protected muscle tissue in rats against CCL4-induced muscle damage by reducing oxidative stress and inflammation. Moreover, it downregulated malondialdehyde (MDA), NF-κB, TNF-α, and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) and upregulated antioxidant enzymes (catalase and glutathione [GSH]), together with its transcriptional factor nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2). Furthermore, suppressing B-cell lymphoma 2 (bcl-2) and inducing caspase-3 led the damaged tissues to apoptosis

[31][32]. It has also been shown to improve muscle dysfunction in cuprizone-induced demyelinated mice by imparting mitochondrial protection, oxidative stress prevention, and Sirt3 overexpression

[32][33].

Urolithins are metabolites obtained from the transformation of ellagic acid. Urolithin A and urolithin B have positive effects on muscle cells. Urolithin A, a mitophagy activator, stimulated muscle function and exercise capacity by inducing autophagy and mitophagy in rodents

[33][34]. In a mouse model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), it enhanced muscle function and survival rate by preserving mitophagy, respiratory capacity, and muscle stem cell regeneration ability. Mitochondrial dysfunction, which is the causative agent of DMD, was prevented via urolithin A treatment

[34][35]. Moreover, skeletal muscle cell angiogenesis was increased by urolithin A through an increase in ATP and NAD+ levels. Angiogenesis was upregulated by urolithin A via the Sirt1–PGC-1α pathway

[35][36]. Urolithin B induced the growth and differentiation of C2C12 cells, as well as hypertrophy, in denervation-induced muscle in mice. It decreased muscle atrophy by activating protein synthesis and inhibiting protein degradation. The anabolic activity of urolithin B was attributed to the activation of the androgen receptor, which activates the mTOR pathway. Additionally, it suppressed the upregulation of ubiquitin ligases, MAFbx/atrogin-1, MuRF-1, and myostatin

[36][37]. Pomegranate, which is a rich source of ellagic acid, protected tibialis anterior muscle loss in TNF-α induced muscle atrophy. This protective effect was mediated by the suppression of the inflammatory cytokines, TNF-α, IL-1β, monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1), and NF-κB signalling-mediated ubiquitin ligases; however, it preserved the Akt/mTOR protein synthesis pathway

[37][38].

Among the various hydroxycinnamic acids, ferulic acid (FA), chlorogenic acid, and caffeic acid have been reported to have positive effects on muscle. In mouse C2C12 myotubes, ferulic acid increased the MyHC protein (MyHC-I and MyHC-IIa) and decreased fast-type MyHC-IIb expression. The mRNA expression of sirtuin1 (Sirt1), PGC-1α, and myocyte enhancer factor 2C (MEF2C) was induced by FA. These effects were mediated by the phosphorylation of AMPK, followed by Sirt1 activation, as inhibition of AMPK or Sirt-1 abolished the effects of FA

[38][39]. In another study, the administration of FA promoted the growth of both fast glycolytic and slow oxidative muscle in dexamethasone (Dex)-induced myopathic rats by downregulating myostatin and oxidative stress. FA induced the expression of mechano growth factor and enhanced the antioxidant enzymes superoxide dismutase (SOD), GSH, and catalase in the tibialis anterior (TA) and soleus muscles

[39][40]. In a zebrafish model, FA administration for 30 days caused the hypertrophic growth of fast-type skeletal muscle via the phosphorylation of zebrafish target of rapamycin, p70S6K, and 4E-BP1. Moreover, the myogenic transcription factors myogenin, MyoD, and serum response factor were increased via FA treatment

[40][41]. Chlorogenic acid has been reported to increase muscle strength by enhancing mitochondrial function and cellular energy metabolism in resistance training-induced rats

[41][42]. Caffeic acid, which is found in fruits, wine, and coffee, exhibits some interesting effects against muscle injury. The administration of caffeic acid phenethyl ester (CAPE) protected muscles against eccentric exercise-induced injury in rats. This effect was mediated by the blockage of NF-κB activation and NF-κB-mediated prooxidant and proinflammatory responses. Inflammation-related genes, i.e.,

IL-β,

MCP-1,

iNOS, and

COX-2, and the oxidative stress marker MDA were significantly suppressed via CAPE treatment

[42][43]. Caffeic acid in combination with curcumin improved autosomal recessive spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) by promoting

SMN2 gene expression, which controls the severity of SMA. Etiologically, SMA is caused by a loss of α-motor neurons in the anterior horn of the spinal cord, leading to neurogenic muscle atrophy

| EGCG |

| Aged mice and late passaged C2C12 cells |

| Attenuated muscle atrophy and protein degradation |

|

| upregulated miR-486-5p |

| [ |

| 62 |

| ] |

| EGCG |

Starvation and TNF-α-induced C2C12 atrophy |

Attenuation of muscle wasting

inhibited protein degradation and activated protein synthesis |

[63] |

| EGCG |

Tumor induced LLC and C57Bl/6 mice atrophy |

Attenuates muscle atrophy

inhibits NF-κB, atrogin-1 and MuRF-1 |

[64] |

| EGCG |

Mouse model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy |

Protected from muscle necrosis

improved muscle functions |

[65] |

| EGCG |

HLS-induced muscle atrophy in aged rats |

Improved Plantaris muscle weight and fiber size

reduced pro-apoptotic signaling |

[66] |

| EGCG |

HLS-induced muscle atrophy in aged rats |

Maintained autophagy signaling in disuse muscle

prevented autophagy and apoptosis during reloading |

[67] |

| EGCG |

Dex-induced C2C12 myotubes and tail-suspended mice |

Prevented muscle atrophy

suppressed MuRF1 |

[68] |

Green tea extracts

(EGCG) |

HF diet-induced muscle atrophy in SAMP8 mice |

Ameliorated HF-induced muscle wasting

Decreased insulin resistance and LECT2 expression |

[69] |

| EGCG |

Live skeletal muscle fibers model |

Promoted nuclear efflux of Foxo1

activated PI3K/Akt pathway |

[70] |

| Catechin (ECG+EGCG) |

C2C12 cells and Cardiotoxin induced C56BL/6 mice |

Stimulated muscle stem cell activation and differentiation for muscle regeneration. |

[71] |

| Catechin |

Downhill running-induced muscle damage in ICR mice |

Attenuated downhill running-induced muscle damage

suppressed oxidative stress and inflammation |

[72] |

| catechins |

Tail-suspension induced muscle atrophy in mice |

Minimized contractile dysfunction and muscle atrophy

decreased oxidative stress |

[73] |

| Flavanones |

Hesperidin |

Human skeletal muscle cell and mice |

Reverted aging-induced decrease in muscle fiber size

increased mitochondrial function and running performance

reduced oxidative stress |

[74] |

| Naringenin |

L6 and C2C12 cells |

Delays skeletal muscle differentiation |

[75] |

| 8-Prenylnaringe-nin (8-PN) |

Denervated Mice |

Prevented muscle atrophy

suppressed Atrogin-1

Phosphorylated Akt |

[76] |

| 8-PN |

C2C12 myotubes and casting-induced muscle atrophy in mice |

Reversed casting-induced loss of tibialis anterior muscle

activated PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway |

[77] |

| Flavones |

Apigenin |

Aged Mice |

Relieved muscle atrophy and increased myofiber size

inhibited hyperactive mitophagy/ autophagy and apoptosis. |

[78] |

| Apigenin |

Obesity-induced muscle atrophy in Mice |

Attenuated muscle atrophy and mitochondrial dysfunctions. |

[79] |

| Apigenin |

Denervated-induced muscle atrophy in mice |

Protected muscle loss

Upregulated MyHC

reduced TNF-α and MuRF-1 level |

[80] |

| Apigenin |

C57BL/6 mice and C2C12 cells |

Promotes skeletal muscle hypertrophy

enhanced myogenic differentiation

upregulated Prmt7-PGC-1α-GPR56 pathway |

[81] |

| Flavones |

LPS-induced muscle atrophy in C2C12 myotube |

Prevented myotube atrophy

suppressed Atrgoin-1

inhibited JNK phosphorylation |

[82] |

| Luteolin |

LLC-induced muscle atrophy in mice |

Prevented muscle atrophy

downregulated MuRF-1, Atrgoin-1, cytokines/inflammatory markers |

[83] |

| Luteolin |

Dex-Induced muscle atrophy in mice |

Prevented muscle atrophy

Induced antioxidant and antiapoptotic activity |

[84] |

| Isoflavones |

Isoflavone (genistein and daidzein) |

TNF-α induced C2C12 myotubes |

Suppressed MuRF1 promoter activity and myotube atrophy |

[85] |

| Isoflavone |

Tumor-induced muscle atrophy in mice |

Prevented muscle wasting

suppressed ubiquitin ligases expression |

[86]. |

| Isoflavone |

Denervation-induced muscle atrophy in mice |

Prevented muscle fiber atrophy

decreased apoptosis-dependent signaling. |

[87] |

| Genistein |

Denervation-induced muscle atrophy in mice |

Mitigated soleus muscle atrophy |

[88] |

| Genistein |

C2C12 myoblast |

Enhanced proliferation and differentiation

downregulated miR-222 |

[89] |

| Daidzein |

Young female mice |

Down-regulated ubiquitin-specific protease 19

increased soleus muscle mass |

[90] |

| Daidzein |

Cisplatin-induced

LLC bearing mice |

Alleviated skeletal muscle atrophy

prevented protein degradation |

[91] |

| Daidzein |

C2C12 cells |

Promotes myogenic differentiation and myotube hypertrophy |

[92] |

| Soy protein |

Rats |

Improved muscle function |

[93] |

| Formononetin (isoflavone) |

CKD rats and TNF-α-induced C2C12 myotubes atrophy |

Prevented muscle wasting

suppressed MuRF-1, MAFbx and myostatin expression

Phosphorylated PI3K, Akt and FoxO3a |

[94] |

| Glabridin |

Dex-induced atrophy (in vitro and in vivo) |

Inhibited protein degradation and muscle atrophy in vitro and in vivo |

[95] |

| Flavonols |

Quercetin |

HF-diet induced muscle atrophy in mice |

Protected muscle mass and muscle fiber size

reduced ubiquitin ligases and inflammatory cytokines |

[96] |

| Quercetin |

TNF-α induced myotube and Obesity induced mice muscle atrophy |

Averted muscle atrophy

Upregulated HO-1 and Nrf2

Inactivates NF-kB |

[97] |

| Quercetin |

Murine C26 cancer-cachexia model |

Prevented body and muscle weight loss

tended to decrease Atrgoin-1 and MuRF-1 |

[98] |

| Quercetin |

A549 cells injected tumor model in mice |

Prevented loss of GM

and protein degradation

Increased MyHC level |

[99] |

| Quercetin |

Dex-Induced C2C12 cell injury |

Increased C2C12 cell viability

exerted antiapoptotic effects

reduce oxidative stress

regulates mitochondrial membrane potential |

[100] |

| Quercetin |

Dex-induced-muscle atrophy in mice |

Prevented muscle loss

reduced myostatin, atrgoin-1 and MuRF-1

increased Akt phosphorylation |

[101] |

| Quercetin |

Tail-suspension induced muscle atrophy in mice |

Prevented GM loss

suppressed ubiquitin ligases and lipid peroxidation |

[102] |

| Quercetin |

Denervation-induced muscle atrophy in mice |

Prevented muscle atrophy

suppressed mitochondrial hydrogen peroxide generation

elevated mitochondrial biogenesis |

[103] |

| Quercetin Glycosides |

Male C57BL/6J aged mice |

Improved motor performance

Increased muscle mass |

[104] |

| Quercetin |

Mice |

Mitochondrial biogenesis

Increased endurance and running capacity |

[105] |

| Morin |

LLC cell-bearing mice and C2C12 myotubes atrophy |

Suppressed muscle wasting and myofiber size reduction by

binding to ribosomal protein S10 |

[106] |

| Morin |

Dex- induced atrophy of C2C12 skeletal myotubes |

Prevented protein degradation

reduced oxidative stress, Atrogin-1, MuRF-1 and Cbl-b

Phosphorylated Foxo3a |

[107] |

| Anthocyanins |

Delphinidin |

Dex-induced C2C12 atrophy and tail-suspension induced atrophy in mice |

Suppressed MuRF-1 expression

Prevented muscle weight loss

upregulated miR-23a and NFATc3 |

[108] |

| Delphinidin |

Dex-induced C2C12 atrophy and tail-suspension induced atrophy in mice |

Suppressed disused-muscle loss

suppressed Cbl-b and stress related gene |

[109] |

| Delphinidin |

LPS-induced atrophy in C2C12 myotubes |

Reduced atrogin-1 expression insignificantly |

[82] |

| Cyanidin |

Dystrophic alpha-sarcoglyan (Sgca) null mice |

Reduced progression of muscular dystrophy

Reduced inflammation and fibrosis |

[110] |

2.3. Flavanols

Among the three main compounds of the flavanol group, EC and epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) have been extensively studied regarding their effects in muscle atrophy. In aged mice and human muscle samples, EC administration reversed the aging-induced expression of myostatin and β-galactosidase while increasing the level of follistatin, MyoD, and myogenin, which are the growth and differentiation factors of muscles

[52]. Moreover, supplementation with EC for 37 weeks exerted an antiaging effect and increased the survival of mice from 39% to 69%, while attenuating aging-induced muscle loss. Furthermore, it prevented the aging-induced decline in the metabolism of nicotinate and nicotinamide, which play a vital role in mitochondrial respiration and oxidative phosphorylation

[53]. EC counteracted the wasting of oxidative muscle (slow-type MyHC) in disuse-induced mice by increasing angiogenesis in muscle and improving mitochondrial function. It also decreased Foxo1 and angiogenic inhibitor thrombospondin-1 (TSP-1), whereas it increased the PGC-1β, mTOR, and AKT proteins

[54]. Similarly, in denervated rats, treatment with EC for 30 days prevented muscle wasting via the downregulation of the UPS. This effect was achieved by downregulating Foxo1, MAFbx/atrogin-1, MuRF-1, and protein ubiquitination

[55]. In the Becker muscular dystrophic muscle, EC increased muscle regeneration by upregulating Myf5, MyoD, myogenin, MEF2a, and follistatin and downregulating myostatin. It acted as mitochondrial bioenergetics by promoting mitochondrial biogenesis through PGC1-α

[56]. In C2C12 cells, EC treatment enhanced myotube growth and mitochondrial biogenesis by activating the transcription factors Nrf2, TFAM, and citrate synthase through G-protein-coupled estrogen receptor (GPER) activation

[57]. EC also increased myogenic differentiation through the stimulation of the promyogenic signaling pathways p38MAPK and Akt. Moreover, it elevated MyoD activity as well as the myogenic conversion and differentiation of fibroblasts

[58]. In high-fat (HF) diet-induced aged mice, EC attenuated muscle damage by reducing the expression of Foxo1 and MuRF-1. Moreover, it boosted physical performance and prompted the growth and differentiation factor MEF2A

[59]. We reported previously that EC treatment suppressed the expression of the ubiquitin ligases atrogin-1 and MuRF-1 induced by 3D clinorotation in C2C12 myoblasts and myotubes via the dephosphorylation of extracellular regulated kinase (ERK) signaling

[60].

EGCG is another component of the flavanol group that is mainly found in green tea. In a sarcopenic rat model, aged rats exhibited muscle atrophy associated with an increase in protein degradation and a decrease in anabolic factors compared with their younger counterparts. EGCG treatment suppressed muscle atrophy and preserved gastrocnemius muscle (GM) mass. Treatment with EGCG significantly reduced the ubiquitin–proteasome complex (19S and 20S), myostatin, and the E3 ubiquitin ligases atrogin-1 and MuRF-1 in aged rats, whereas it upregulated the anabolic factors IGF-1 and IL-15

[61]. Similarly, EGCG treatment attenuated age-related GM loss via Akt phosphorylation and subsequent inhibition of FoxO1a-mediated MuRF1 and atrogin-1 expression in aged senescence-accelerated mouse-prone 8 (SAMP8) mice and in late-passage C2C12 cells. These effects were mediated by the upregulation of miRNA-486-5p via EGCG. Thus, it inhibited myostatin/miRNA/ubiquitin–proteasome signaling

[62]. In starvation- and TNF-α-induced C2C12 cells, EGCG treatment significantly suppressed protein degradation and activated protein synthesis. Additionally, it increased the phosphorylation of Akt and Foxo3a and attenuated the 20S proteasome, atrogin-1, and MuRF-1

[63]. These results are consistent with those of our previous study, in which EGCG decreased 3D-clinorotation-induced atrogin-1 and MuRF-1 expression by dephosphorylating ERK

[60]. In Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC) tumor-bearing mice, EGCG attenuated muscle atrophy by suppressing NF-κB and its downstream mediators MuRF-1 and MAFbx

[64]. Similarly, in the dystrophic mdx5Cv mouse model, EGCG protected the fast-twitch extensor digitorum longus (EDL) muscle from necrosis and stimulated muscle function, thus showing a positive effect on dystrophic abnormalities

[65]. In disuse-induced aged rats, EGCG improved plantaris muscle weight and size during reloading followed by unloading by suppressing proapoptotic signaling in reloaded muscle

[66]. In a similar model, EGCG induced autophagy during unloading, whereas it suppressed autophagy in the reloaded condition, to improve muscle health

[67]. Moreover, EGCG administration suppressed MuRF1 expression in Dex-induced C2C12 cells through the activation of the 67-kDa laminin receptor (67LR)

[68]. The same study reported the protection afforded by EGCG against GM loss in disused mice, which was further potentiated by the use of eriodyctiol

[68]. EGCG prevented HF-induced muscle atrophy in SAMP8 mice by improving insulin resistance, together with a change in serum leukocyte cell-derived chemotaxin 2 (LECT2)

[69]. Interestingly, in human skeletal muscle fibers, ECGC treatment had a similar effect, as did the insulin growth factor 1 (IGF-1) and insulin, thus suppressing the action of the atrophy-promoting transcription factor Foxo1 via the net translocation of Foxo1 out of the nucleus

[70].

Catechin flavanol-activated satellite cells, which induce the Myf5 transcription factor via Akt phosphorylation. It also promoted myogenic differentiation by inducing the myogenic markers myogenin and muscle creatine kinase for muscle regeneration in C2C12 cells. The same study, which was performed using mice, reported increased fiber size and muscle regeneration after EGCG treatment

[71]. Furthermore, it attenuated downhill running-induced muscle damage by suppressing muscle oxidative stress and inflammation and hastened the recovery of physical performance in mice

[72]. Catechin also diminished unloading-induced contractile dysfunction and muscle atrophy in unloaded mice by suppressing oxidative stress

[73].

2.4. Flavanones

Flavanones, also called dihydroflavones, are another class of flavonoid compounds that are most commonly found in citrus fruits, such as oranges, lemons, and grapes. Hesperidin, naringenin, and eriodyctiol are the main compounds in this group. They exhibit antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antitumor, and cholesterol-lowering effects

[111]. In aged mice, hesperetin reverted the aging-induced decrease in muscle fiber size and improved running performance. The same in vitro study using human skeletal muscle cells showed that hesperidin increased mitochondrial function by promoting ATP production and mitochondrial spare capacity. Moreover, it reduced oxidative stress in vitro and in vivo

[74], proving that this compound is a potential agent for the retardation of sarcopenia and mitochondrial dysfunctionalities. Conversely, naringenin delayed the differentiation of skeletal muscle cells by hampering ERα-mediated Akt phosphorylation

[75]. Intriguingly, we found that the chemical modification of naringenin to 8-prenylnaringenin (8-PN) by substituting the 8-prenyl group in the hydrogen atom of the eighth position of the molecule significantly alleviated denervation-induced loss of GM, whereas intact naringenin was found to be ineffective. Moreover, 8-PN, which acts as a powerful phytoestrogen, attenuated the induction of atrogin-1 by denervation and accelerated Akt phosphorylation. The accumulation of 8-PN in the GM was 10-fold higher than that observed for naringenin, which suggested that the prenylation of naringenin is required for its accumulation in the GM and for improving muscle atrophy

[76]. Similarly, we reported that 8-PN treatment in mouse C2C12 skeletal myotubes increased the phosphorylation of PI3K, Akt, and p70S6K1, which was associated with its estrogenic activity. It also enhanced the weight of the tibialis anterior muscle in casting-induced muscle-atrophied mice

[77].

2.5. Flavones

Flavones represent one of the important groups of flavonoids and are commonly found in fruits, vegetables, and plant-derived beverages, such as those from grapefruits, oranges, parsley, onions, tea, chamomile, and wheat sprouts

[112]. Apigenin (AP), luteolin, tangeritin, and chrysin are the main compounds of this group. Among them, AP and luteolin have been highlighted for their antiatrophic effect in vitro and in vivo. AP administration prevented aging-induced loss of TA, EDL, and soleus muscle mass, and increased the muscle fiber size in aged mice. The attenuation of muscle atrophy was associated with a reduction of oxidative stress and the inhibition of hyperactive mitophagy/autophagy and apoptosis. AP increased SOD and GSH expression and enhanced mitochondrial function by increasing ATP levels and mitochondrial biogenesis by inducing the expression of PGC-1α, TFAM, Nrf-1, and ATP5B

[78]. Furthermore, AP treatment ameliorated obesity-induced skeletal muscle atrophy and increased muscle mass, the CSA of muscle fibers, and exercise capacity. Moreover, it suppressed the expression of the atrophic genes

MuRF1 and

atrogin-

1. The expression of the inflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β was attenuated by AP in the serum and GM muscle tissue. The mitochondrial function was enhanced by AP through the upregulation of citrate synthase, complex-I, and complex-II activities, leading to increased OXPHOS. AP also caused increased mitochondrial biogenesis by upregulating PGC-1α, TFAM, cytochrome c, somatic (CyCs), and mtDNA content. The same study found that AP suppressed palmitic acid-induced muscle atrophy and mitochondrial dysfunction in C2C12 myotubes, and further reported that the beneficial effect of AP was regulated by AMPK activation

[79]. In denervation-induced mice, AP attenuated the loss of GM and soleus muscle weight and increased muscle fiber CSA. Additionally, it upregulated the total MyHC protein and the mRNA expression of MyHC-IIb in the GM, as well as MyHC-IIa in the soleus muscle, with suppression of MuRF1 expression. Furthermore, TNF-α was downregulated both in the GM and soleus muscles, whereas IL-6 was decreased only in the soleus muscle

[80]. Similarly, AP increased the mRNA expression of MyHC-I, MyHC-IIa, and MyHC-IIb in the quadriceps muscles of mice. The G-protein-coupled receptor 56 (GPR56) and its ligand, collagen III, were upregulated, as were PGC-1α, PGC-1α1, PGC-1α4, IGF1, and IGF2. The protein arginine methyltransferase 7 (Prmt7) was also enhanced by AP. The same in vitro study found that AP stimulated C2C12 myogenic differentiation by regulating MyoD protein expression. Thus, the beneficial effect of AP was regulated via the Prmt7–PGC-1α–GPR56 pathway, as well as by the Prmt7–p38–myoD pathway

[81].

Previously, we reported that treatment with AP and luteolin prevents the lipopolysaccharides (LPS)-mediated reduction of myotube diameter by suppressing atrogin-1/MAFbx expression through the inhibition of the JNK signaling pathway in C2C12 myotubes

[82]. Moreover, in cachexia-induced muscle atrophy, luteolin treatment protected against the loss of GM, which was associated with the attenuation of the expression of inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α and IL-6) and the ubiquitin ligases MuRF-1 and Atrogin-1. Here MuRF-1 expression was reduced via the deactivation of NF-κB both at the transcription and translation level, whereas atrogin-1 was suppressed by the downregulation of p-38

[83]. Luteolin also improved GM mass and strength in Dex-induced myopathy by exerting its antioxidant and antiapoptotic activities. Moreover, it reduced oxidative stress with attenuation of MDA and enhancement of the GSH antioxidant. Finally, it suppressed apoptosis by regulating caspase-3 expression

[84].

2.6. Isoflavones

Isoflavones are flavonoid compounds that are most commonly present in soybeans, soy foods, and legumes. They act as phytoestrogen and exhibit pseudohormonal activity in conjugation with the ER. They possess antioxidant, anticancer, antimicrobial, and anti-inflammatory activities

[113]. Genistein and daidzein are the representative elements of this group. Isoflavones have been reported to exert favorable effects on inflammation and glucocorticoid-induced muscle myopathies. We reported the effects of isoflavone treatment (daidzein and genistein) in muscles in vitro and in vivo. Isoflavone suppressed TNF-α-induced C2C12 myotube atrophy by attenuating MuRF-1 activity. This effect was regulated by AMPK-mediated SIRT-1 activation, in which SIRT-1 caused deacetylation of p65, which is involved in the activation of MuRF-1

[85]. Similar effects were noted in an in vivo model, where isoflavone supplementation in tumor-bearing mice attenuated the decrease in GM mass and myofiber size. Isoflavone decreased the expression of the ubiquitin ligases atrogin-1 and MuRF-1 by reducing the phosphorylation of ERK

[86]. In denervation-induced muscle atrophy in mice, supplementation with the isoflavone aglycone (AglyMax) at a 0.6% dose significantly attenuated fiber atrophy by suppressing apoptosis-dependent signaling, as manifested by decreased apoptotic nuclei, but not caspase-3

[87]. In the same model of atrophy, genistein protected against soleus muscle atrophy by suppressing the transcription of FOXO1 via the recruitment of FOXO1 to ER-α. Sequentially, the activation of ER-α, attenuates FOXO1 and subsequently the expression of atrogin-1 and MuRF-1

[88]. In C2C12 myoblasts, genistein treatment at a lower concentration prompted myoblast proliferation and differentiation; however, at higher concentrations, it inhibited both of these processes. It also downregulated miR-222, therefore increasing the miR-222 target genes

MyoG,

MyoD, and

ER-α, which are necessary for the differentiation of myoblasts

[89]. Dietary daidzein decreased the mRNA and protein expression of ubiquitin-specific protease 19, which is a negative regulator of muscle mass, through the recruitment of ERβ, and increased soleus muscle mass in young female mice but not in male mice

[90]. In cisplatin-induced LLC-tumor-bearing mice, daidzein attenuated the loss of myofiber CSA and prevented changes in fiber-type proportion. Moreover, it inhibited protein degradation by suppressing atrogin-1 and MuRF1 via the regulation of the Glut4/AMPK/FoxO pathway

[91]. A similar effect was suggested by an in vitro experiment, in which cisplatin-induced C2C12 myotube atrophy was reversed by inhibiting the Glut4/AMPK/FoxO pathway

[91]. Furthermore, In Dex-induced atrophy in C2C12 myotubes, daidzein prevented myotube atrophy and promoted myotube growth and myogenic differentiation. The promyogenic activity was mediated by two kinases, Akt and P38MAPK, which in turn activated the key myogenic transcription factor MyoD. Moreover, daidzein encouraged myotube growth via the activation of the Akt/mTOR/S6K pathway

[92]. In high-fat diet-induced rats, chronic soy protein consumption resulted in improved muscle function, regardless of muscle mass or fiber cross-section area improvement

[93]. Formononetin, which is an isoflavone that is found in

Astragalus membranaceus, ameliorated chronic kidney disease (CKD)-induced muscle atrophy. In formononetin-treated mice, body weight, the weight of the tibialis anterior and GM, and the CSA of skeletal muscles were significantly improved compared with CKD mice. Moreover, it effectively suppressed MuRF-1, MAFbx, and myostatin expression in TNF-α-induced cells and CKD-mice, whereas the phosphorylation of PI3K, Akt, and Foxo3a was enhanced by formononetin in both in vitro and in vivo models

[94]. Glabridin, which is a prenylated isoflavone, inhibited Dex-induced protein degradation in C2C12 myotubes and in the tibialis anterior muscle of mice through the suppression of the ubiquitin ligases MuRF1 and Cbl-b but not atrogin-1. Mechanistically, glabridin inhibited the binding of Dex to its receptor, i.e., the glucocorticoid receptor. Moreover, glabridin prevented the Dex-induced phosphorylation of p38 and FoxO3a, which act as upstream molecules to enhance the expression of ubiquitin ligases

[95].

2.7 Flavonols

Flavonols are PPs that belong to the flavonoid family. They are found in a variety of fruits and vegetables, such as apples, apricots, beans, broad beans, broccoli, cherry tomatoes, chives, cranberries, kale, leeks, pears, onions, red grapes, sweet cherries, and white currants. They exert antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, cardioprotective, neuroprotective, anticancer, antibacterial, and antiviral effects

[47][114][47,114]. Among the different compounds of this group, such as kaempferol, quercetin, myricetin, and morin, quercetin is the most-studied compound in the context of muscle atrophy as it acts against obesity, disuse, cachexia, and glucocorticoids.

In obesity-induced muscle atrophy, supplementation with quercetin for 9 weeks prevented the reduction of quadriceps and GM mass and muscle fiber size by attenuating protein degradation through MuRF-1 and Atrogin-1 downregulation. It significantly reduced the expression of macrophage or inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6, MCP-1, F4/80, and CD68), as well as inflammatory cytokine receptors such as toll-like receptors (TLR) and 4-1BB in skeletal muscle. The transcripts of inflammatory receptors and their signaling molecules (ERK, p38MAPK, and NF-κB) were significantly reduced together with atrogin-1 and MuRF-1 in cocultured myotubes/macrophages

[96]. Thus, obesity-induced muscle atrophy was alleviated by quercetin via the modulation of inflammatory cytokines, their receptors, and their downstream signaling pathways

[96]. Quercetin suppressed TNF-α-induced C2C12 myotube atrophy by reducing the ubiquitin ligases atrogin-1 and MuRF-1. The downregulation of ubiquitin ligases was triggered by the inhibition of NF-κB and the activation of Heme Oxygenase 1 (HO-1) in myotubes, as the HO-1 inhibitor, ZnPP abolished the inhibitory actions of quercetin. In the same study, quercetin suppressed the muscle atrophy caused by obesity by upregulating HO-1 and inactivating NF-κB, which was lost in Nrf-2 deficient mice. These results suggest that quercetin suppresses TNF-α-induced muscle atrophy under obese conditions via Nrf2-mediated HO-1 induction accompanied by the inactivation of NF-κB

[97]. Quercetin also limited body weight, GM and tibialis muscle loss in C26-cancer-associated cachectic mice, with a substantial decrease in atrogin-1 but not in MuRF-1 [

98]. Similarly, in an A549-cell-injected tumor mouse model, quercetin increased the antitumor activity of trichostatin A (TSA) and suppressed the TSA-induced loss of GM. It further attenuated the TSA-induced activation of FOXO1, atrogin-1, and MuRF-1. Moreover, oxidative damage and inflammatory cytokines were significantly suppressed by quercetin, and it increased MyHC levels in GM

[99]. In C2C12 cells, treatment with Dex (250 µM) decreased cell viability and exerted apoptosis via hydroxyl-free radical generation. Quercetin treatment prevented Dex-induced cell viability and apoptosis by regulating mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) and reducing ROS production.

[100]. Moreover, in Dex-induced muscle atrophy in mice, quercetin prevented the loss of the GM by suppressing myostatin and the expression of the ubiquitin ligases atrogin-1 and MuRF-1. The suppression of myostatin was attributed to the phosphorylation of Akt

[101]. In tail suspension-induced disuse muscle atrophy, we found that injection of quercetin into the GM prevented its loss. Additionally, it suppressed protein degradation by attenuating the expression of the ubiquitin ligases atrogin-1 and MuRF-1 by decreasing oxidative stress, as manifested by a reduced TBARS level

[102]. We also reported the effects of quercetin in denervation-induced muscle atrophy, in which pre-intake of quercetin prevented the loss of muscle mass and the atrophy of GM fibers by opposing decreased mitochondrial genesis and increased mitochondrial hydrogen peroxide release. Overall, it increased the antioxidant capacity of mitochondria, together with increased PGC-1α expression

[103]. Furthermore, quercetin decreased the 3D-clinorotation-induced expression of atrogin-1 and MuRF-1 via the dephosphorylation of ERK

[60], which is indicative of its efficacy in disuse muscle atrophy. Interestingly, long-term (24 weeks) oral treatment with quercetin glycoside effectively improved motor performance and increased muscle (quadratus femoris, gastrocnemius, tibialis anterior, and soleus) mass during the early stages of aging

[104]. The stimulation of mitochondrial biogenesis by quercetin was also reported in a mouse experiment. Intake of quercetin for 7 days increased the mRNA expression of PGC-1α and SIRT1, mtDNA, and cytochrome c concentration. Both the maximal endurance capacity and voluntary wheel-running activity of mice were enhanced by quercetin supplementation

[105].

Morin is another compound in the flavonol group that is commonly found in plants of the Moraceae family

[115]. We reported the antiatrophic effect of morin in cachexia and in a Dex-induced muscle atrophy model. In LLC cell-bearing mice, intake of morin prevented the reduction of muscle wet weight and myofiber size by suppressing cancer growth via binding to the ribosomal protein S10 (RPS10)

[106]. In Dex-induced muscle atrophy in C2C12 myotubes, morin attenuated E3 ubiquitin ligases atrogin-1, MuRF-1, and Cbl-b and preserved the fast-type and slow-type MyHC protein content. These actions were mediated by a decrease in oxidative stress and an increase in the phosphorylation of Foxo3a. Morin also upregulated PGC-1α

[107].

23.8. Anthocyanins

Anthocyanins are natural pigments belonging to the flavonoid family. The blue, purple, red, and orange color of many fruits and vegetables stem from the presence of anthocyanins

[116]. The most common anthocyanidins in plants are delphinidin, cyanidin, petunidin, pelargonidin, peonidin, and malvidin. Berries, red grapes, cereals, purple maize, vegetables, and red wine are the chief sources of anthocyanins. They exhibit various health benefits, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anticancer, antidiabetic, hepatoprotective, and neuroprotective effects

[116][117][116,117]. The antiatrophic effects of delphinidin and cyanidin have been reported.

Delphinidin, which is one of the major anthocyanidins, suppresses MuRF1 expression by preventing the downregulation of miR-23a and the nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFATc3) in Dex-induced C2C12 cells

[108]. In the same in vivo study using tail-suspended mice, delphinidin suppressed GM loss by reducing MuRF-1 expression and increasing miR-23a and NFATc3. miR23a, which is a micro-RNA (miRNA), decreases MuRF-1 expression by suppressing its mRNA translation. Hence, the beneficial effect of delphinidin occurred via the modulation of the NFATc3/miR-23a pathway

[109]. Similarly, delphinidin suppressed the Dex-induced expression of Cbl-b in C2C12 myotubes. In the same study, oral administration of delphinidin attenuated the loss of quadriceps muscle induced by unloading in mice. These effects were mediated by the attenuation of the expression of Cbl-b and stress-related genes

[109]. In our previous study, we found that delphinidin insignificantly suppressed the LPS-induced expression of atrogin-1

[82]. A cyanidin-rich diet delayed the progression of muscular dystrophies by attenuating inflammation and oxidative stress in dystrophic alpha-sarcoglycan (Sgca) gene null mice

[110].

3. Conclusion

The polyphenols reported in this review have been found to prevent muscle atrophy via the suppression of muscle protein degradation, mainly by downregulating ubiquitin ligases, and the promotion of protein synthesis, myogenesis, and mitochondrial quality in in vitro and in vivo studies. The main mechanisms associated with the beneficial effects of PPs on muscle atrophy are: inhibition of inflammatory cytokines, oxidative stress, myostatin, and muscle atrophy-related ubiquitin ligases: Atrogin-1, MuRF-1, and Cbl-b. Anti-atrophic effects of PPs are also mediated by activation of the IGF-1 signaling pathway, follistatin, miRNAs, mitochondrial biogenesis, and myogenic differentiation factors involved in myogenesis. Therefore, PPs having effects on the attenuation of muscle proteolysis and maintenance of muscle mass could facilitate the avenue for designing suitable therapeutic strategies for the attenuation of skeletal muscle atrophy and the promotion of muscle health.